The Night of the Jack-O’-Lantern

from Ramona and Her Father by Beverly Cleary

The Quimby family has a big problem. Mr. Quimby has lost his job, and

everyone is worried and cross. Seven-year-old Ramona does her best to

make people smile, but it isn’t easy. Her older sister Beatrice, who is

always called Beezus, has become a real grouch. Even Picky-picky, the

family cat, stalks around angrily.

i ,t x [j-\’c]{.smallcaps} arc

“Please pass the tommmy-toes,” said Ramona, hoping to make someone in

the family smile. She felt good when her father smiled as he passed her

the bowl of stewed tomatoes. He smiled less and less as the days went by

and he had not found work. Too often he was just plain cross. Ramona had

learned not to rush home from school and ask, “Did you find a job today,

Daddy?” Mrs. Quimby always seemed to look anxious these days, either

over the cost of groceries or money the family owed. Beezus had turned

into a regular old grouch, because she dreaded Creative Writing and

perhaps because she had reached that difficult age Mrs. Quimby was

always talking about, although Ramona found this hard to believe.

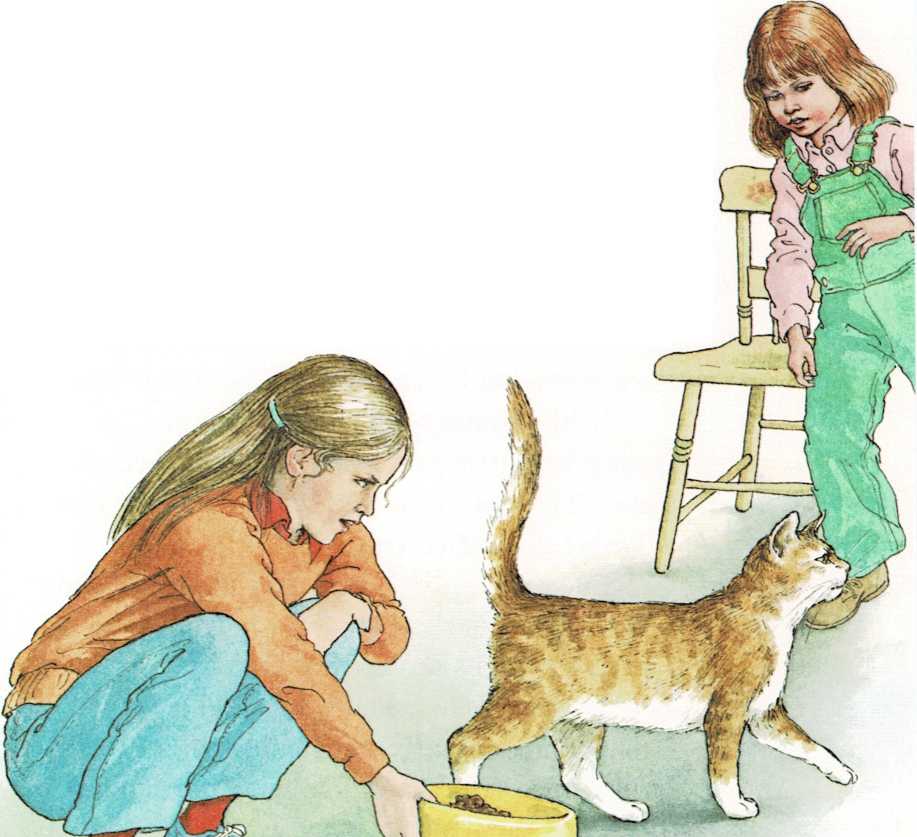

Even Picky-picky was not himself. He lashed his tail and stalked angrily

away from his dish when Beezus served him Puss-puddy, the cheapest brand

of cat food Mrs. Quimby could find in the market.

All this worried Ramona. She wanted her father to smile and joke, her

mother to look happy, her sister to be cheerful, and

Picky-picky to eat his food, wash his

whiskers, and purr the way he used to.

“And so,” Mr. Quimby was saying, “at the end of the interview for the

job, the man said he would let me know if anything turned up.”

Mrs. Quimby sighed. “Let’s hope you hear from him. Oh, by the way, the

car has been making a funny noise. A sort of tappety-tappety sound.”

“It’s Murphy’s Law,” said Mr. Quimby. “Anything that can go wrong will.”

Ramona knew her father was not joking this time. Last week, when the

washing machine refused to work, the Quimbys had been horrified by the

size of the repair bill.

“I like tommy-toes,” said Ramona, hoping her little joke would work a

second time. This was not exactly true, but she was willing to sacrifice

truth for a smile.

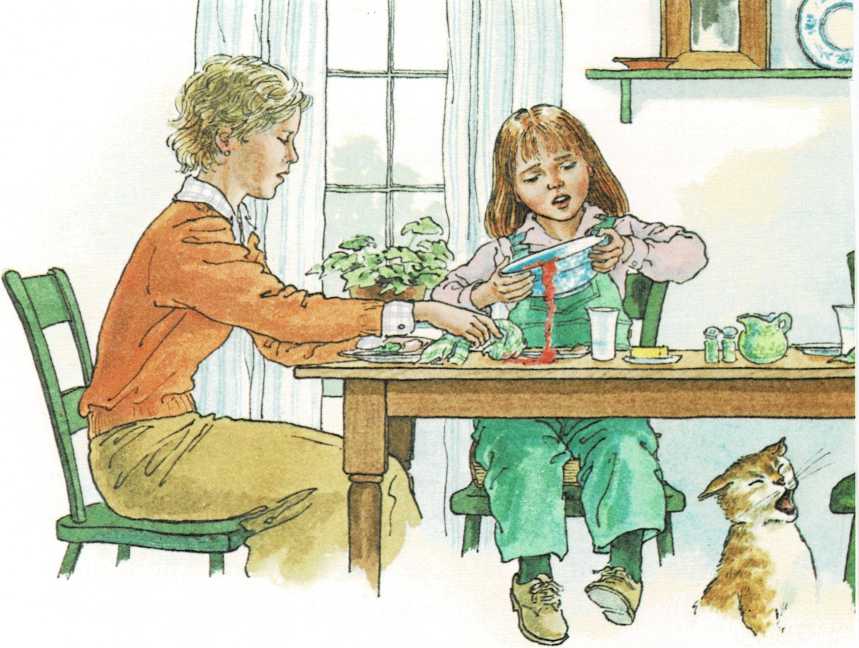

Since no one paid any attention, Ramona spoke louder as she lifted the

bowl of stewed tomatoes. “Does anybody want any tommy-toes?” she asked.

The bowl tipped. Mrs. Quimby silently reached over and wiped spilled

juice from the table with her napkin.

Crestfallen, Ramona set the bowl down. No one had smiled.

“Ramona,” said Mr. Quimby, “my grandmother used to have a saying. ‘First

time is funny, second time is silly, third time is a spanking.’ “

Ramona looked down at her place mat. Nothing seemed to go right lately.

Picky-picky must have felt the same way. He sat down beside Beezus and

meowed his Grossest meow.

Mr. Quimby lit a cigarette and asked his older daughter, “Haven’t you

fed that cat yet?”

Beezus rose to clear the table. “It wouldn’t do any good. He hasn’t

eaten his breakfast. He won’t eat that cheap Puss-puddy.”

“Too bad about him.” Mr. Quimby blew a cloud of smoke toward the

ceiling.

“He goes next door and mews as if we never give him anything to eat,”

said Beezus. “It’s embarrassing.”

“He’ll just have to learn to eat what we can afford,” said Mr. Quimby.

“Or we will get rid of him.”

This statement shocked Ramona. Picky-picky had been a member of the

family since before she was born.

“Well, I don’t blame him,” said Beezus, picking up the cat and pressing

her cheek against his fur. “Puss-puddy stinks.”

Mr. Quimby ground out his cigarette.

“Guess what?” said Mrs. Quimby, as if to change the subject. “Howie’s

grandmother drove out to visit her sister, who lives on a farm, and her

sister sent in a lot of pumpkins for jack-o’-lanterns for the

neighborhood children. Mrs. Kemp gave us a big one, and it’s down in the

basement now, waiting to be carved.”

“Me! Me!” cried Ramona. “Let me get it!”

“Let’s give it a real scary face,” said Beezus, no longer difficult.

“I’ll have to sharpen my knife,” said Mr. Quimby.

“Run along and bring it up, Ramona,” said Mrs. Quimby with a real smile.

Relief flooded through Ramona. Her family had returned to normal. She

snapped on the basement light, thumped down the stairs, and there in the

shadow of the furnace pipes, which reached out like ghostly arms, was a

big, round pumpkin. Ramona grasped its scratchy stem, found the pumpkin

too big to lift that way, bent over, hugged it in both arms, and raised

it from the cement floor. The pumpkin was heavier than she had expected,

and she must not let it drop and smash all over the concrete floor.

“Need some help, Ramona?” Mrs. Quimby called down the stairs.

“I can do it.” Ramona felt for each step with her feet and emerged,

victorious, into the kitchen.

“Wow! That is a big one.” Mr. Quimby was sharpening his jackknife on a

whetstone while Beezus and her mother hurried through the dishes.

“A pumpkin that size would cost a lot at the market,” Mrs. Quimby

remarked. “A couple of dollars, at least.”

“Let’s give it eyebrows like last year,” said Ramona.

“And ears,” said Beezus.

“And lots of teeth,” added Ramona.

There would be no jack-o’-lantern with one tooth and three triangles for

eyes and nose in the Quimbys’ front window on Halloween. Mr. Quimby was

the best pumpkin carver on Klickitat Street. Everybody knew that.

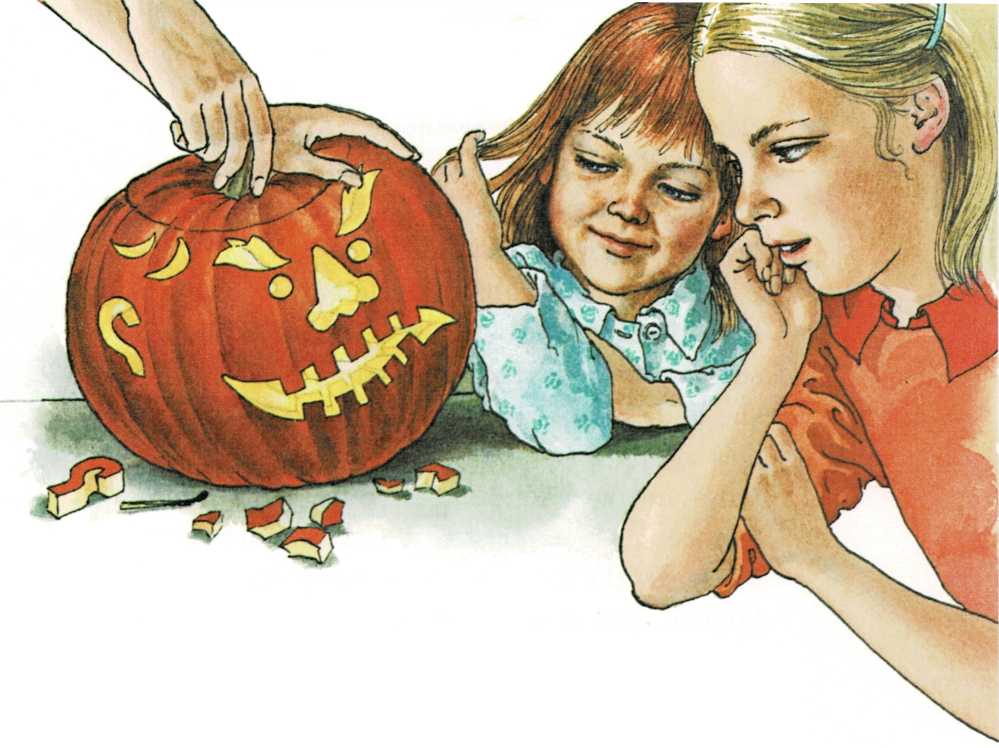

\”Hmm. Let’s see now.” Mr. Quimby studied the pumpkin, turning it to

find the best side for the face. “I think the nose should go about

here.” With a pencil he sketched a nose-shaped nose, not a triangle,

while his daughters leaned on their elbows to watch.

“Shall we have it smile or frown?” he asked.

“Smile!” said Ramona, who had had enough of frowning.

“Frown!” said Beezus.

The mouth turned up on one side and down on the other. Eyes were

sketched and eyebrows. “Very expressive,” said Mr. Quimby. “Something

between a leer and a sneer.” He cut a circle around the top of the

pumpkin and lifted it off for a lid.

Without being asked, Ramona found a big spoon for scooping out the

seeds.

Picky-picky came into the kitchen to see if something beside Puss-puddy

had been placed in his dish. When he found that it had not, he paused,

sniffed the unfamiliar pumpkin smell, and with his tail twitching

angrily stalked out of the kitchen. Ramona was glad Beezus did not

notice.

“If we don’t let the candle burn the jack-o’-lantern, we can have

pumpkin pie,” said Mrs. Quimby. “I can even freeze some of the pumpkin

for Thanksgiving.”

Mr. Quimby began to whistle as he carved with skill and care, first a

mouthful of teeth, each one neat and square, then eyes and jagged,

ferocious eyebrows. He was working on two ears shaped like question

marks, when Mrs. Quimby said, “Bedtime, Ramona.”

“I am going to stay up until Daddy finishes,” Ramona informed her

family. “No ifs, ands, or buts.”

“Run along and take your bath,” said Mrs. Quimby, “and you can watch

awhile longer.”

Because her family was happy once more, Ramona did not protest. She

returned quickly, however, still damp under her pajamas, to see what her

father had thought of next. Hair, that’s what he had thought of,

something he could carve because the pumpkin was so big. He cut a few

C-shaped curls around the hole in the top of the pumpkin before he

reached inside and hollowed out a candle holder in the bottom.

“There,” he said and rinsed his jackknife under the kitchen faucet. “A

work of art.”

Mrs. Quimby found a candle stub, inserted it in the pumpkin, lit it, and

set the lid in place. Ramona switched off the light. The jack-o’-lantern

leered and sneered with a flickering flame.

“Oh, Daddy!” Ramona threw her arms around her father. “It’s the

wickedest jack-o’-lantern in the whole world.”

Mr. Quimby kissed the top of Ramona’s head. “Thank you. I take that as a

compliment. Now run along to bed.”

Ramona could tell by the sound of her father’s voice that he was

smiling. She ran off to her room without thinking up excuses for staying

up just five more minutes, added a postscript to her prayers thanking

God for

the big pumpkin, and another asking him to find her father a job, and

fell asleep at once, not bothering to tuck her panda bear in beside her

for comfort.

In the middle of the night Ramona found herself suddenly awake without

knowing why she was awake. Had she heard a noise? Yes, she had. Tense,

she listened hard. There it was again, a sort of thumping, scuffling

noise, not very loud but there just the same. Silence. Then she heard it

again. Inside the house. In the kitchen. Something was in the kitchen,

and it was moving.

Ramona’s mouth was so dry she could barely whisper, “Daddy!” No answer.

More thumping. Someone bumped against the wall. Someone, something was

coming to get them. Ramona thought about the leering, sneering face on

the kitchen table. All the ghost stories she had ever heard, all the

ghostly pictures she had ever seen flew through her mind. Could the

jack-o’-lantern have come to life? Of course not. It was only a pumpkin,

but still— A bodyless, leering head was too horrifying to think about.

Ramona sat up in bed and shrieked, “Daddy!”

A light came on in her parents’ room, feet thumped to the floor,

Ramona’s tousled father in rumpled pajamas was silhouetted in Ramona’s

doorway, followed by her mother tugging a robe on over her short

nightgown.

“What is it, Baby?” asked Mr. Quimby. Both Ramona’s parents called her

Baby when they were worried about her, and tonight Ramona was so

relieved to see them she did not mind.

“Was it a bad dream?” asked Mrs. Quimby.

“Th-there’s something in the kitchen.” Ramona’s voice quavered.

Beezus, only half-awake, joined the family. “What’s happening?” she

asked. “What’s going on?”

“There’s something in the kitchen,” said Ramona, feeling braver.

“Something moving.”

“Sh-h!” commanded Mr. Quimby.

Tense, the family listened to silence.

“You just had a bad dream.” Mrs. Quimby came into the room, kissed

Ramona, and started to tuck her in.

Ramona pushed the blanket away. “It was not st bad dream,” she

insisted. “I did too hear something. Something spooky.”

“All we have to do is look,” said Mr. Quimby, reasonable—and bravely,

Ramona thought. Nobody would get her into that kitchen.

Ramona waited, scarcely breathing, fearing for her father’s safety as he

walked down the hall and flipped on the kitchen light. No shout, no yell

came from that part of the house. Instead her father laughed, and Ramona

felt brave enough to follow the rest of the family to see what was

funny.

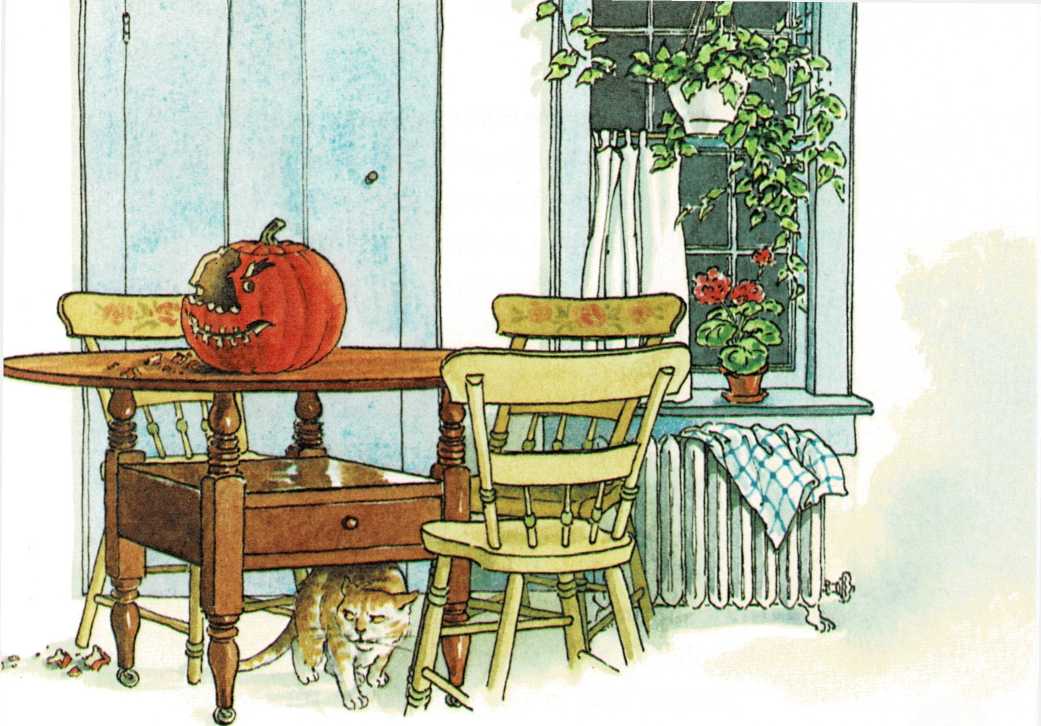

There was a strong smell of cat food in the kitchen. What Ramona saw,

and what Beezus saw, did not strike them as one bit

funny. Their jack-o’-lantern, the jack-o’-lantern their father had

worked so hard to carve, no longer had a whole face. Part of its

forehead, one ferocious eyebrow, one eye, and part of its nose were

gone, replaced by a jagged hole edged by little teeth marks. Picky-picky

was crouched in guilt under the kitchen table.

The nerve of that cat. “Bad cat! Bad cat!” shrieked Ramona, stamping her

bare foot on the cold linoleum. The old yellow cat fled to the dining

room, where he crouched under the table, his eyes glittering out of the

darkness.

Mrs. Quimby laughed a small rueful laugh. “I knew he liked canteloupe,

but I had no idea he liked pumpkin, too.” With a butcher’s knife she

began to cut up the remains of the jack-o’-lantern, carefully removing,

Ramona noticed, the parts with teeth marks.

“I told you he wouldn’t eat that awful Puss-puddy.” Beezus was

accusing her father of denying their cat. “Of course he had to eat our

jack-o’-lantern. He’s starving.”

“Beezus, dear,” said Mrs. Quimby. “We simply cannot afford the brand of

food Picky-picky used to eat. Now be reasonable.”

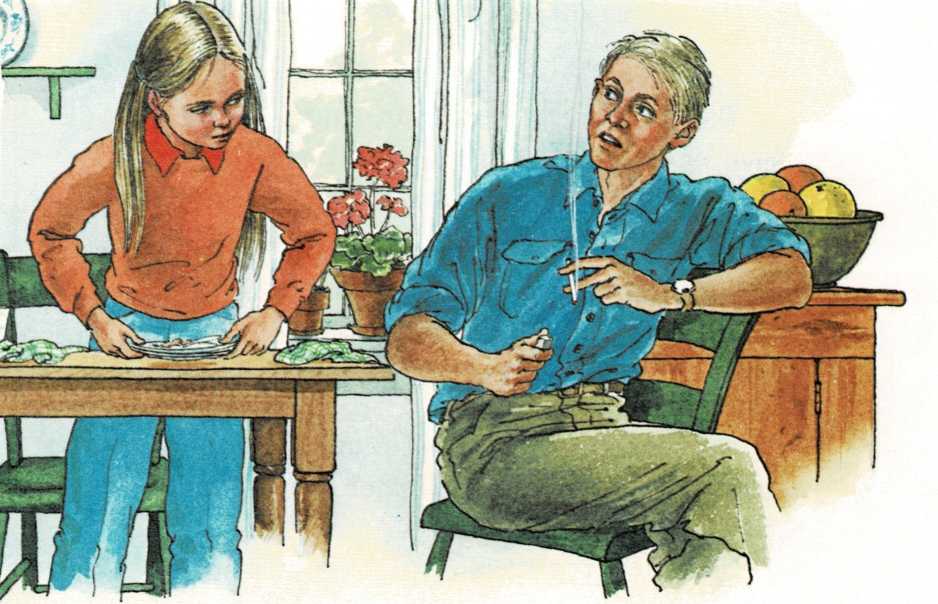

Beezus was in no mood to be reasonable. “Then how come Daddy can afford

to smoke?” she demanded to know.

Ramona was astonished to hear her sister speak this way to her mother.

Mr. Quimby looked angry. “Young lady,” he said, and when he called

Beezus young lady, Ramona knew her sister had better watch out. “Young

lady, I’ve heard enough about that old tom cat and his food. My

cigarettes are none of your business.”

Ramona expected Beezus to say she was sorry or maybe burst into tears

and run to her room. Instead she pulled Picky-picky out from under the

table and held him to her chest as if she were shielding him from

danger. “They are too my business,” she informed her father. “Cigarettes

can kill you. Your lungs will turn black and you’ll die! We made

posters about it at school. And besides, cigarettes pollute the air!”

Ramona was horrified by her sister’s daring, and at the same time she

was a tiny bit pleased. Beezus was usually well-behaved while Ramona was

the one who had tantrums. Then she was struck by the meaning of her

sister’s angry words and was frightened.

“That’s enough out of you,” Mr. Quimby told Beezus, “and let me remind

you that if you had shut that cat in the basement as you were supposed

to, this would never have happened.”

Mrs. Quimby quietly stowed the remains of the jack-o’-lantern in a

plastic bag in the refrigerator.

Beezus opened the basement door and gently set Picky-picky on the top

step. “Night-night,” she said tenderly.

“Young lady,” began Mr. Quimby. Young lady again! Now Beezus was really

going to catch it. “You are getting altogether too big for your britches

lately. Just be careful how you talk around this house.”

Still Beezus did not say she was sorry. She did not burst into tears.

She simply stalked off to her room.

Ramona was the one who burst into tears. She didn’t mind when she and

Beezus quarreled. She even enjoyed a good fight now and then to clear

the air, but she could not bear it when anyone else in the family

quarreled, and those awful things Beezus said—were they true?

“Don’t cry, Ramona.” Mrs. Quimby put her arm around her younger

daughter. “We’ll get another pumpkin.”

“B-but it won’t be as big,” sobbed Ramona, who wasn’t crying about the

pumpkin at all. She was crying about important things like her father

being cross so much now that he wasn’t working and his lungs turning

black and Beezus being so disagreeable when before she had always been

so polite (to grown-ups) and anxious to do the right thing.

“Come on, let’s all go to bed and things will look brighter in the

morning,” said Mrs. Quimby.

“In a few minutes.” Mr. Quimby picked up a package of cigarettes he had

left on the kitchen table, shook one out, lit it, and sat down, still

looking angry.

Were his lungs turning black this very minute? Ramona wondered. How

would anybody know, when his lungs were inside him? She let her mother

guide her to her room and tuck her in bed.

“Now don’t worry about your jack-o’-lantern. We’ll get another pumpkin.

It won’t be as big, but you’ll have your jack-o’-lantern.” Mrs. Quimby

kissed Ramona good-night.

“Nighty-night,” said Ramona in a muffled voice. As soon as her mother

left, she hopped out of bed and pulled her old panda bear out from under

the bed and tucked it under the covers beside her for comfort. The bear

must have been dusty because Ramona sneezed.

“Gesundheit!” said Mr. Quimby, passing by her door. “We’ll carve

another jack-o’-lantern tomorrow. Don’t worry.” He was not angry with

Ramona.

Ramona snuggled down with her dusty bear. Didn’t grown-ups think

children worried about anything but jack-o’-lanterns? Didn’t they know

children worried about grown-ups?

Ramona and Beezus think up a great plan to get their father to quit

smoking—as you will discover when you read the rest of Ramona and Her

Father. And if you liked this story, you will want to read others of

the more than twenty books Beverly Cleary has written, such as Ramona

the Brave, Henry and Ribsy, and Henry and Beezus.