Pippi Goes to the Circus from Pippi Longstocking by Astrid

Lindgren translated from the Swedish by Florence Lamborn

Way out at the end of a tiny little town was an old overgrown garden,

and in the garden was an old house, and in the house lived Pippi

Longstocking. She was nine years old, and she lived there all alone. She

had no mother and no father, and that was of course very nice because

there was no one to tell her to go to bed just when she was having the

most fun, and no one who could make her take cod-liver oil when she much

preferred caramel candy.

Once upon a time Pippi had had a father of whom she was extremely fond.

Naturally she had had a mother too, but that was so long ago that Pippi

didn’t remember her at all. Her mother had died when Pippi was just a

tiny baby. . . .

Her father Pippi had not forgotten. He was a sea captain who sailed on

the great ocean, and Pippi had sailed with him in his ship until one day

her father blew overboard in a storm and disappeared. But Pippi

was absolutely certain that he would come back. She would never believe

that he had drowned; she was sure he had floated until he landed on an

island inhabited by cannibals. And she thought he had become the king of

all the cannibals and went around with a golden crown on his head all

day long. . . .

Her father had bought the old house in the garden many years ago. He

thought he would live there with Pippi when he grew old and couldn’t

sail the seas any longer. And then this annoying thing had to happen,

that he blew into the ocean, and while Pippi was waiting for him to come

back she went straight home to Villa Villekulla. That was the name of

the house. It stood there ready and waiting for her. One lovely summer

evening she had said good-by to all the sailors on her father’s boat.

They were all so fond of Pippi, and she of them.

“So long, boys,” she said and kissed each one on the forehead. “Don’t

you worry about me. I’ll always come out on top.”

Two things she took with her from the ship: a little monkey whose name

was Mr. Nilsson—he was a present from her father—and a big suitcase

full of gold pieces. The sailors stood up on the deck and watched as

long as they could see her. She walked straight ahead without looking

back at all, with Mr. Nilsson on her shoulder and her suitcase in her

hand.

“A remarkable child,” said one of the sailors as Pippi disappeared in

the distance.

He was right. Pippi was indeed a remarkable child. The most remarkable

thing about her was that she was so strong. She was so very strong that

in the whole wide world there was not a single police officer who was as

strong as she. Why, she could lift a whole horse if she wanted to! And

she wanted to. She had a horse of her own that she had bought with one

of her many gold pieces the day she came home to Villa Villekulla. She

had always longed for a horse, and now here he was living on the porch.

When Pippi wanted to drink her afternoon coffee there, she simply lifted

him down into the garden.

Beside Villa Villekulla was another garden and another house. In that

house lived a father and mother and two charming children, a boy and a

girl. The boy’s name was Tommy and the girl’s Annika….

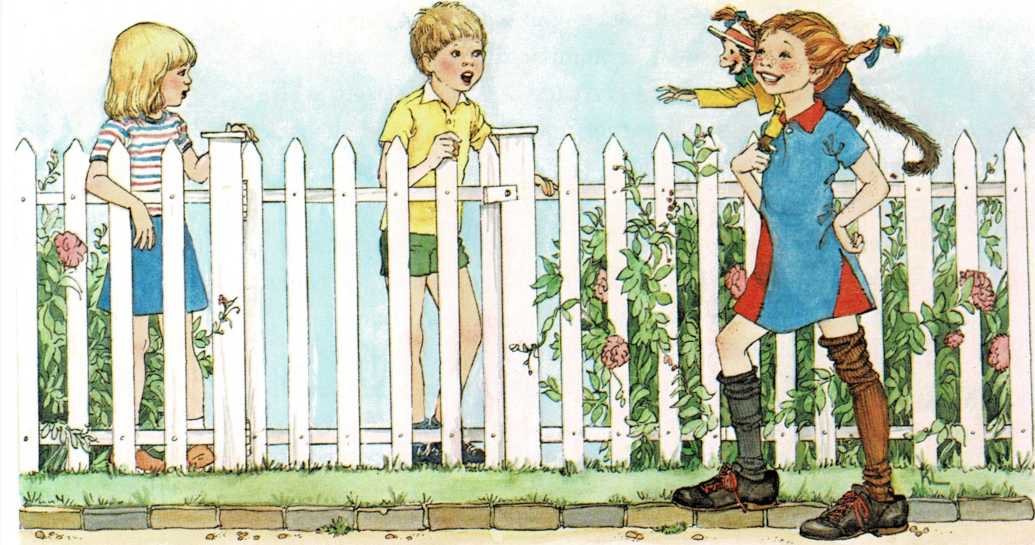

On that lovely summer evening when Pippi for the first time stepped over

the threshold of Villa Villekulla, Tommy and Annika were not at home.

They had gone to visit their grandmother for a week; and so they had no

idea that anybody had moved into the house next door. On the first day

after they came home again they stood by the gate, looking out onto the

street, and even then they didn’t know that there actually was a

playmate so near. Just as they were standing there considering what they

could do and wondering whether anything exciting was likely to happen or

whether it was going to be one of those dull days when they couldn’t

think of anything to play—-just then the gate of Villa Villekulla

opened and a little girl stepped out. She was the most remarkable

girl Tommy and Annika had ever seen. She was Miss Pippi Longstocking out

for her morning promenade. This is the way she looked:

Her hair, the color of a carrot, was braided in two tight braids that

stuck straight out. Her nose was the shape of a very small potato and

was dotted all over with freckles. It must be admitted that the mouth

under this nose was a very wide one, with strong white teeth. Her dress

was rather unusual. Pippi herself had made it. She had meant it to be

blue, but there wasn’t quite enough blue cloth, so Pippi had sewed

little red pieces on it here and there. On her long thin legs she wore a

pair of long stockings, one brown and the other black; and she had on a

pair of black shoes that were exactly twice as long as her feet. These

shoes her father had bought for her in South America so that Pippi

should have something to grow into, and she never wanted to wear any

others.

But the thing that made Tommy and Annika open their eyes widest of all

was the monkey sitting on the strange girl’s shoulder. It was a little

monkey, dressed in blue pants, yellow jacket, and a white straw hat.

Pippi walked along the street with one foot on the sidewalk and the

other in the gutter. Tommy and Annika watched as long as they could see

her. In a little while she came back, and now she was walking backward.

That was because she didn’t want to turn around to get home. When she

reached Tommy’s and Annika’s gate she stopped.

The children looked at each other in silence. At last Tommy spoke. “Why

did you walk backward?”

“Why did I walk backward?” said Pippi. “Isn’t this a free country? Can’t

a person walk any way he wants to? For that matter, let me tell you that

in Egypt everybody walks that way, and nobody thinks it’s the least bit

strange.”

“How do you know?” asked Tommy. “You’ve never been in Egypt, have you?”

“I’ve never been in Egypt? Indeed I have. That’s one thing you can be

sure of. I have been all over the world and seen many things stranger

than people walking backward. I wonder what you would have said if I had

come along walking on my hands the way they do in Farthest India.”

“Now^r^ you must be lying,” said Tommy.

Pippi thought a moment. “You’re right,” she said sadly, “I am lying.”

“It’s wicked to lie,” said Annika, who had at last gathered up enough

courage to speak.

“Yes, it’s very wicked to lie,” said Pippi even more sadly. “But I

forget it now and then. And how can you expect a little child whose

mother is an angel and whose father is king of a cannibal island and who

herself has sailed on the ocean all her life—how can you expect her to

tell the truth always? And for that matter,” she continued, her whole

freckled face lighting up, “let me tell you that in the Belgian Congo

there is not a single person who tells the truth. They lie all day long.

Begin at seven in the morning and keep on until sundown. So if I should

happen to lie now and then, you must try to excuse me and to remember

that it is only because I stayed in the Belgian Congo a little too long.

We can be friends anyway, can’t we?”

“Oh, sure,” said Tommy and realized suddenly that this was not going to

be one of those dull days.

“By the way, why couldn’t you come and have breakfast with me?” asked

Pippi.

“Why not?” said Tommy. “Come on, let’s go.”

“Oh, yes, let’s,” said Annika.

“But first I must introduce you to Mr. Nilsson,” said Pippi, and the

little monkey took off his cap and bowed politely.

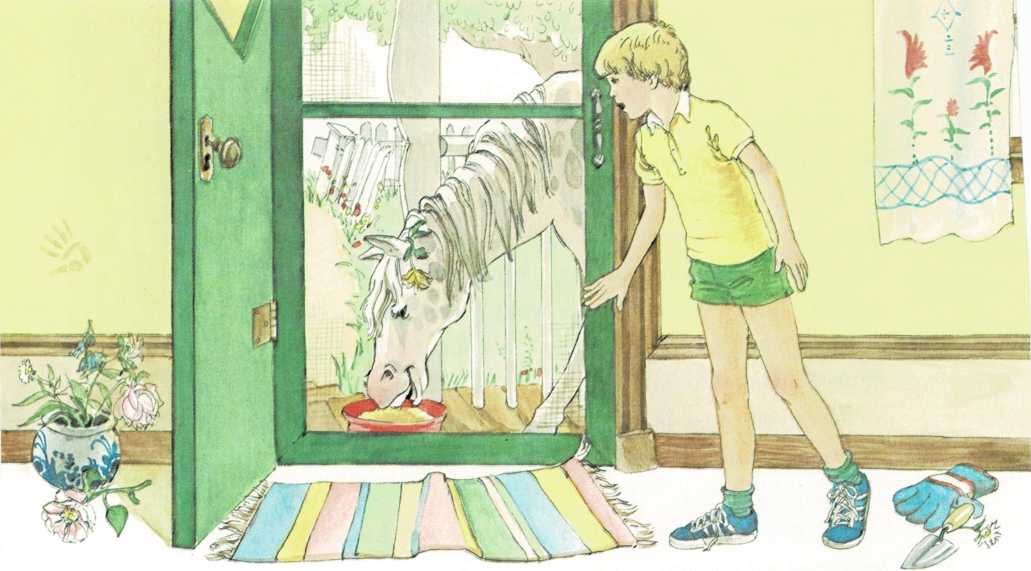

Then they all went in through Villa Villekulla’s tumbledown garden gate,

along the gravel path, bordered with old moss-covered trees—really

good climbing trees they seemed to be—up to the house, and on to the

porch. There stood the horse, munching oats out of a soup bowl.

“Why do you have a horse on the porch?” asked Tommy. All horses he knew

lived in stables.

“Well,” said Pippi thoughtfully, “he’d be in the way in the kitchen, and

he doesn’t like the parlor.”

Tommy and Annika patted the horse and then went on into the house. It

had a kitchen, a parlor, and a bedroom. But it certainly looked as if

Pippi had forgotten to do her Friday cleaning that week. Tommy and

Annika looked around cautiously just in case the King of the Cannibal

Isles might be sitting in a corner

somewhere. They had never seen a cannibal king in all their lives. But

there was no father to be seen, nor any mother either.

Annika said anxiously, “Do you live here all alone?”

“Of course not!” said Pippi. “Mr. Nilsson and the horse live here too.”

“Yes, but I mean, don’t you have any mother or father here?”

“No, not the least little tiny bit of a one,” said Pippi happily.

“But who tells you when to go to bed at night and things like that?”

asked Annika.

“I tell myself,” said Pippi. “First I tell myself in a nice friendly

way; and then, if I don’t mind, I tell myself again more sharply; and if

I still don’t mind, then I’m in for a spanking—see?”

Tommy and Annika didn’t see at all but they

thought maybe it was a good way. Meanwhile they had

\’ ■\’ ■

come out into the kitchen…. Pippi took three eggs and threw them up

in the air. One fell down on her head and broke so that the yolk ran

into her eyes, but the others she caught skillfully in a bowl, where

they smashed to pieces.

“I always did hear that egg yolk was good for the hair,” said Pippi,

wiping her eyes. “You wait and see—mine will soon begin to grow so

fast it crackles….”

While she was speaking Pippi had neatly picked the eggshells out of the

bowl with her fingers. Now she

took a bath brush that hung on the wall and began to beat the pancake

batter so hard that it splashed all over the walls. At last she poured

what was left onto a griddle that stood on the stove.

When the pancake was brown on one side she tossed it halfway up to the

ceiling, so that it turned right around in the air, and then she caught

it on the griddle again. And when it was ready she threw it straight

across the kitchen right onto a plate that stood on the table.

“Eat!” she cried. “Eat before it gets cold!”

And Tommy and Annika ate and thought it a very good pancake.

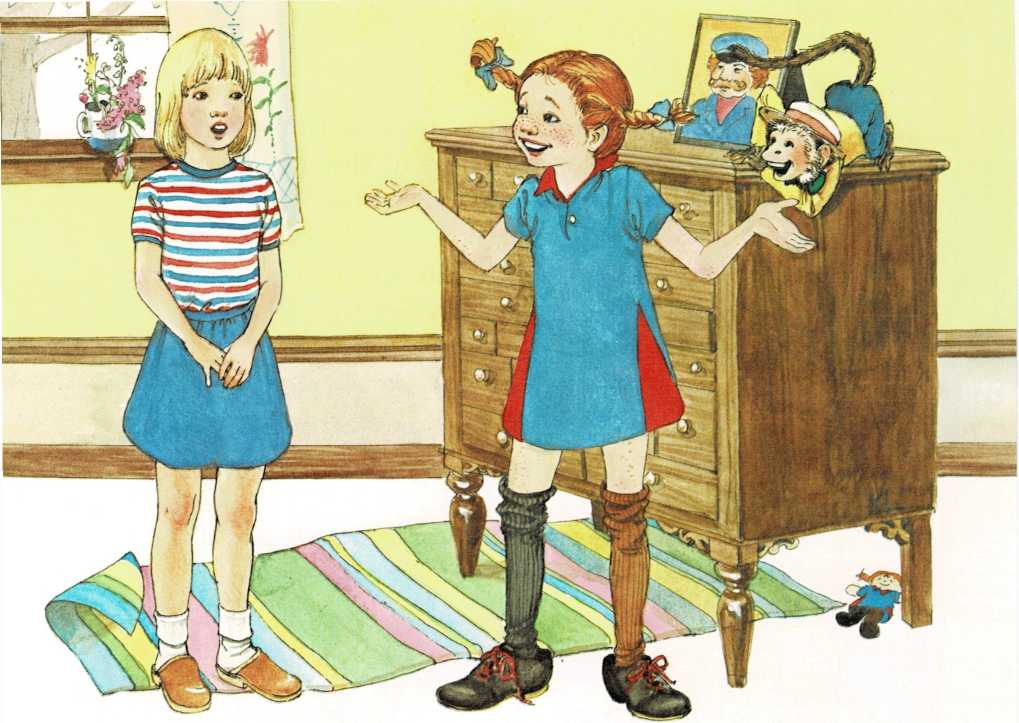

Afterward Pippi invited them to step into the parlor. There was only one

piece of furniture in there. It was a huge chest with many tiny drawers.

Pippi opened the drawers and showed Tommy and Annika all the treasures

she kept there. There were wonderful birds’ eggs, strange shells and

stones, pretty little boxes, lovely silver mirrors, pearl necklaces, and

many other things that Pippi and her father had bought on their journeys

around the world. …

“Suppose you go home now,” said Pippi, “so that you can come back

tomorrow. Because if you don’t go home you can’t come back, and that

would be a shame.”

Tommy and Annika agreed that it would indeed. So they went home—past

the horse, who had now eaten up all the oats, and out through the gate

of Villa Villekulla. Mr. Nilsson waved his hat at them as they left.

Annika woke up early the next morning. She jumped out of bed and ran

over to Tommy.

“Wake up, Tommy,” she cried, pulling him by the

arm, “wake up and let’s go and see that funny girl with the big shoes.”

Tommy was wide awake in an instant.

“I knew, even while I was sleeping, that something exciting was going to

happen today, but I didn’t remember what it was,” he said as he yanked

off his pajama jacket. Off they went to the bathroom; washed themselves

and brushed their teeth much faster than usual; had their clothes on in

a twinkling; and a whole hour before their mother expected them came

sliding down the banister and landed at the breakfast table.

Down they sat and announced that they wanted their hot chocolate right

off that very moment….

A circus had come to the little town, and all the children were begging

their mothers and fathers for permission to go. Of course Tommy and

Annika asked to go too, and their kind father immediately gave them some

money.

Clutching it tightly in their hands, they rushed over to Pippi’s. She

was on the porch with her horse, braiding his tail into tiny pigtails

and tying each one with red ribbon.

“I think it’s his birthday today,” she announced, “so he has to be all

dressed up.”

“Pippi,” said Tommy, all out of breath because they had been running so

fast, “Pippi, do you want to go with us to the circus?”

“I can go with you most anywhere,” answered Pippi, “but whether I can go

to the surkus or not I don’t know, because I don’t know what a surkus

is. Does it hurt?”

“Silly!” said Tommy, “of course it doesn’t hurt; it’s fun. Horses and

clowns and pretty ladies that walk the tightrope.”

“But it costs money,” said Annika, opening her small fist to see if the

shiny half dollar and the quarters were still there.

“I’m rich as a troll,” said Pippi, “so I guess I can buy a surkus all

right. But it’ll be crowded here if I have more horses. The clowns and

the pretty ladies I could keep in the laundry, but it’s harder to know

what to do with the horses.”

“Oh, don’t be silly,” said Tommy, “you don’t buy a circus. It costs

money to go and look at it—see?”

“Preserve us!” cried Pippi and shut her eyes tightly. “It costs money to

look? And here I go around goggling all day long. Goodness knows how

much money I’ve goggled up already!”

Then, little by little, she opened one eye very carefully, and it rolled

round and round in her head. “Cost what it may,” she said, “I must take

a look!”

At last Tommy and Annika managed to explain to Pippi what a circus

really was, and she took some gold pieces out of her suitcase. Then she

put on her hat, which was as big as a millstone, and off they all went.

There were crowds of people outside the circus tent and a long line at

the ticket window. But at last it was Pippi’s turn. She stuck her head

through the window and stared at the dear old lady sitting there.

“How much does it cost to look at you?” Pippi asked.

But the old lady was a foreigner who did not understand what Pippi meant

and answered in broken Swedish.

“Little girl, it costs a dollar and a quarter in the grandstand and

seventy-five cents on the benches and twenty-five cents for standing

room.”

Now Tommy interrupted and said that Pippi wanted

a seventy-five-cent ticket. Pippi put down a gold piece and the old lady

looked suspiciously at it. She bit it too, to see if it was genuine. At

last she was convinced that it really was gold and gave Pippi her ticket

and a great deal of change in silver.

“What would I do with all those nasty little white coins?” asked Pippi

disgustedly. “Keep them and then I can look at you twice. In the

standing room.”

As Pippi absolutely refused to accept any change, the lady changed her

ticket for one for the grandstand and gave Tommy and Annika grandstand

tickets too without their having to pay a single penny. In that way

Pippi, Tommy, and Annika came to sit on some beautiful red chairs right

next to the ring. Tommy and Annika turned around several times to wave

to their schoolmates, who were sitting much farther away.

“This is a remarkable place,” said Pippi, looking

around in astonishment. “But, see, they’ve spilled sawdust all over the

floor! Not that I’m overfussy myself, but that does look careless to

me.”

Tommy explained that all circuses had sawdust on the floor for the

horses to run around in.

On a platform nearby the circus band suddenly began to play a thundering

march. Pippi clapped her hands wildly and jumped up and down with

delight.

“Does it cost money to hear too?” she asked, “or can you do that for

nothing?”

At that moment the curtain in front of the performers’ entrance was

drawn aside, and the ringmaster in a black frock coat, with a whip in

his hand, came running in, followed by ten white horses with red plumes

on their heads.

The ringmaster cracked his whip, and all the horses galloped around the

ring. Then he cracked it again, and all the horses stood still with

their front feet up on the railing around the ring.

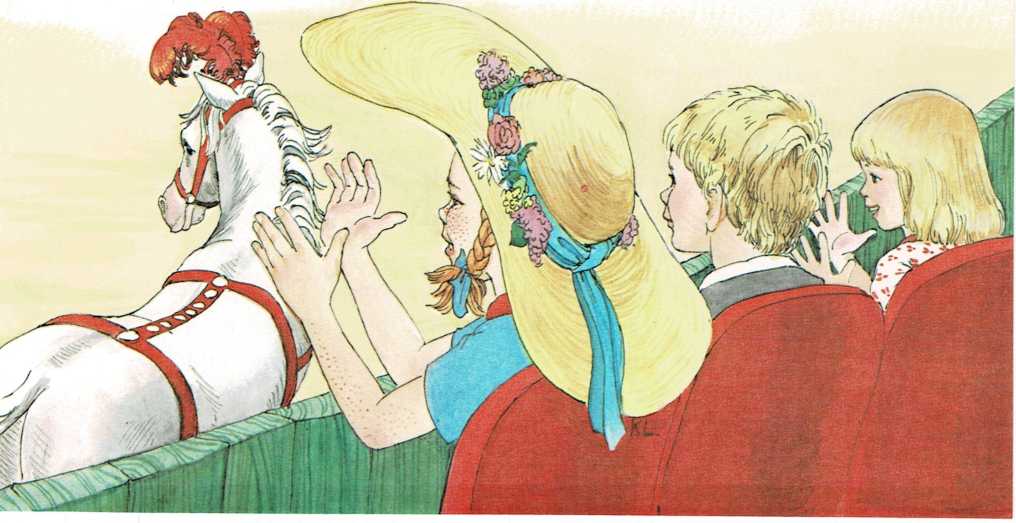

One of them had stopped directly in front of the children. Annika didn’t

like to have a horse so near her

and drew back in her chair as far as she could, but Pippi leaned forward

and took the horse’s right foot in her hands.

“Hello, there,” she said, “my horse sent you his best wishes. It’s his

birthday today too, but he has bows on his tail instead of on his head.”

Luckily she dropped the foot before the ringmaster cracked his whip

again, because then all the horses jumped away from the railing and

began to run around the ring.

When the number was over, the ringmaster bowed politely and the horses

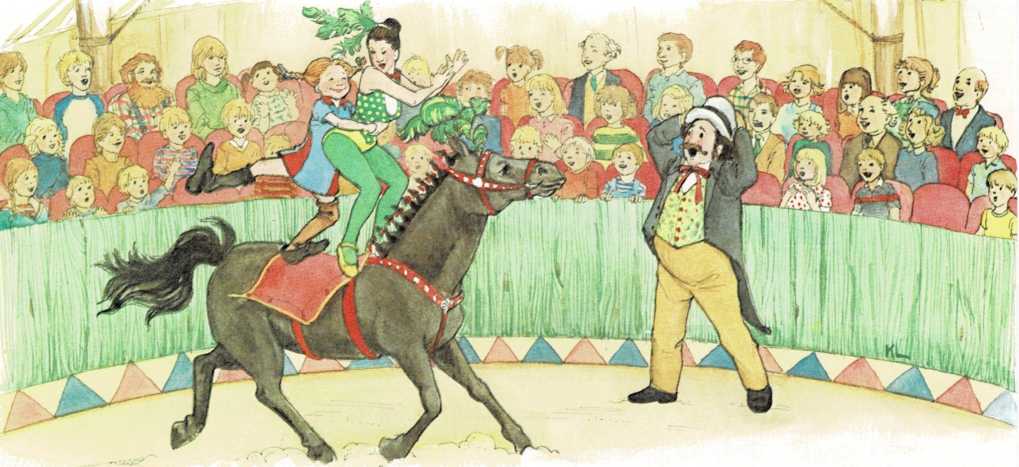

ran out. In an instant the curtain opened again for a coal-black horse.

On its back stood a beautiful lady dressed in green silk tights. The

program said her name was Miss Carmencita.

The horse trotted around in the sawdust, and Miss Carmencita stood

calmly on his back and smiled. But then something happened; just as the

horse passed Pippi’s seat, something came swishing through the air—and

it was none other than Pippi herself. And there she stood on the horse’s

back, behind Miss Carmencita. At first Miss Carmencita was so astonished

that she nearly fell off the horse. Then she got mad. She began to

strike out with her hands behind her back to make Pippi jump off. But

that didn’t work.

“Take it easy,” said Pippi. “Do you think you’re the only one who can

have any fun? Other people have paid too, haven’t they?”

Then Miss Carmencita tried to jump off herself, but that didn’t work

either, because Pippi was holding her tightly around the waist. At that

the audience couldn’t

help laughing. They thought it was so funny to see the lovely Miss

Carmencita held against her will by a little redheaded youngster who

stood there on the horse’s back in her enormous shoes and looked as if

she had never done anything except perform in a circus.

But the ringmaster didn’t laugh. He turned toward an attendant in a red

uniform and made a sign to him to go and stop the horse.

“Is this number already over,” asked Pippi in a disappointed tone, “just

when we were having so much fun?”

“Horrible child!” hissed the ringmaster between his teeth. “Get out of

here!”

Pippi looked at him sadly. “Why are you mad at me?” she asked. “What’s

the matter? I thought we were here to have fun.”

She skipped off the horse and went back to her seat. But now two huge

guards came to throw her out. They took hold of her and tried to lift

her up.

They couldn’t do it. Pippi sat absolutely still, and it was impossible

to budge her although they tried as hard as they could. At last they

shrugged their shoulders and went off….

The next number was about to begin…. The ringmaster … bowed to the

audience, and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, in a moment you will be

privileged to see the Greatest Marvel of all time, the Strongest Man in

the World, the Mighty Adolf, whom no one has yet been able to conquer.

Here he comes, ladies and gentlemen. Allow me to present to you THE

MIGHTY ADOLF.”

And into the ring stepped a man who looked as big as a giant. He wore

flesh-colored tights and had a leopard skin draped around his stomach.

He bowed to the audience and looked very pleased with himself.

“Look at these muscles,” said the ringmaster and squeezed the Mighty

Adolf’s arm where the muscles stood out like balls under the skin.

“And now, ladies and gentlemen, I have a very special invitation for

you. Who will challenge the Mighty Adolf in a wrestling match? Who of

you dares to try his strength against the World’s Strongest Man? A

hundred dollars for anyone who can conquer the Mighty Adolf! A hundred

dollars, ladies and gentlemen! Think of that! Who will be the first to

try?”

Nobody came forth.

“What did he say?” said Pippi.

“He says that anybody who can lick that big man will get a hundred

dollars,” answered Tommy.

“I can,” said Pippi, “but I think it’s too bad to, because he looks

nice.”

“Oh, no, you couldn’t,” said Annika, “he’s the strongest man in the

world.”

“Man, yes,” said Pippi, “but I am the strongest girl in the world,

remember that.”

Meanwhile the Mighty Adolf was lifting heavy iron weights and bending

thick iron rods in the middle just to show how strong he was.

“Oh, come now, ladies and gentlemen,” cried the ringmaster, “is there

really nobody here who wants to earn a hundred dollars? Shall I really

be forced to keep this myself?” And he waved a bill in the air.

“No, that you certainly won’t be forced to do,” said Pippi and stepped

over the railing into the ring.

The ringmaster was absolutely wild when he saw her. “Get out of here! I

don’t want to see any more of you,” he hissed.

“Why do you always have to be so unfriendly?” said Pippi reproachfully.

“I just want to fight with Mighty Adolf.”

“This is no place for jokes,” said the ringmaster. “Get out of here

before the Mighty Adolf hears your impudent nonsense.”

But Pippi went right by the ringmaster and up to Mighty Adolf. She took

his hand and shook it heartily.

“Shall we fight a little, you and I?” she asked.

Mighty Adolf looked at her but didn’t understand a word.

“In one minute I’ll begin,” said Pippi.

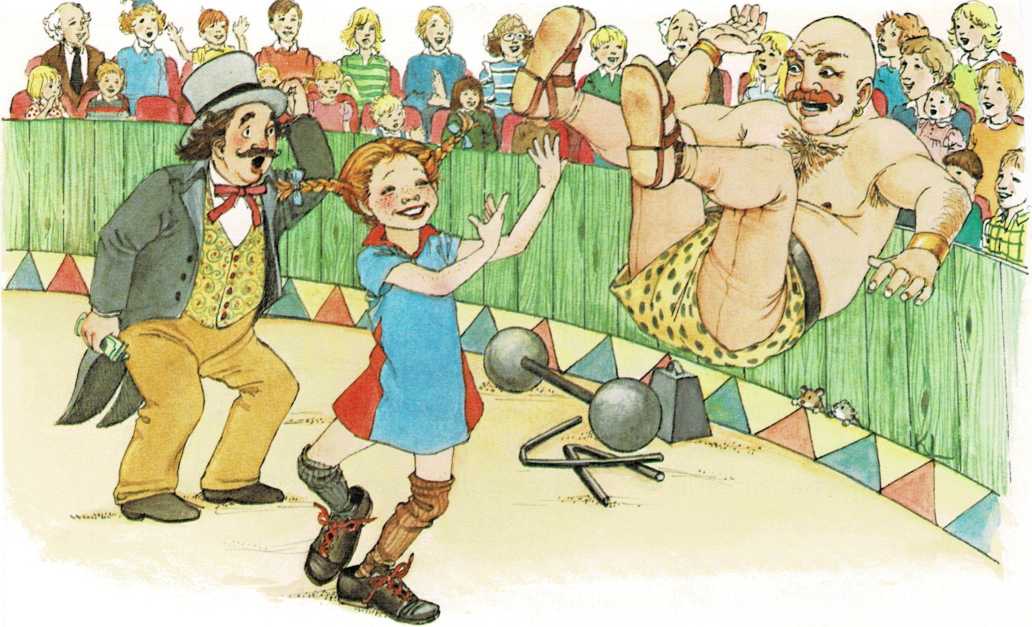

And begin she did. She grabbed Mighty Adolf around the waist, and before

anyone knew what was happening she had thrown him on the mat. Mighty

Adolf leaped up, his face absolutely scarlet.

“Atta girl, Pippi!” shrieked Tommy and Annika, so loudly that all the

people at the circus heard it and began to shriek “Atta girl, Pippi!”

too. The ringmaster sat on the railing, wringing his hands. He was mad,

but Mighty Adolf was madder. Never in his life had he

experienced anything so humiliating as this. And he certainly intended

to show that redheaded girl what kind of a man Mighty Adolf really was.

He rushed at Pippi and caught her around the waist, but Pippi stood firm

as a rock.

“You can do better than that,” she said to encourage him. Then she

wriggled out of his grasp, and in the twinkling of an eye Mighty Adolf

was on the mat again. Pippi stood beside him, waiting. She didn’t have

to wait long. With a roar he was up again, rushing at her.

“Tiddelipom and piddeliday,” said Pippi.

All the people in the tent stamped their feet and threw their hats in

the air and shouted, “Hurrah, Pippi!”

When Mighty Adolf came rushing at her for the third time, Pippi lifted

him high in the air and, with her arms straight above her, carried him

clear around the ring. Then she laid him down on the mat again and held

him there.

“Now, little fellow,” said she, “I don’t think we’ll bother about this

any more. We’ll never have any more fun than we’ve had already.”

“Pippi is the winner! Pippi is the winner!” cried all the people.

Mighty Adolf stole out as fast as he could, and the ringmaster had to go

up and hand Pippi the hundred dollars, although he looked as if he’d

much prefer to eat her.

“Here you are, young lady, here you are,” said he. “One hundred

dollars.”

“That thing!” said Pippi scornfully. “What would I want with that old

piece of paper. Take it and use it to fry herring on if you want to.”

And she went back to her seat.

“This is certainly a long surkus,” she said to Tommy and Annika. “I

think I’ll take a little snooze, but wake me if they need my help about

anything else.”

And then she lay back in her chair and went to sleep at once. There she

lay and snored while the clowns, the sword swallowers, and the snake

charmers did their tricks for Tommy and Annika and all the rest of the

people at the circus.

“Just the same, I think Pippi was best of all,” whispered Tommy to

Annika.

As you have discovered, Pippi is a very unusual girl. In Pippi

Longstocking, the book from which this story came, you can join this

supergirl as she entertains two burglars, upsets a school classroom,

and has many more hilarious adventures. And by then, you will also

want to read Pippi Goes on Board and Pippi in the South Seas.