The “unsinkable” ship

On a bright, clear, and cold night in April, 1912, a sleek, giant ship

plowed through the waters of the North Atlantic. The ship was moving at

a speed of about twenty-two knots (25 miles or 41 kilometers) an hour.

This was too fast, for there had been many warnings by radio that the

water ahead was dotted with icebergs.

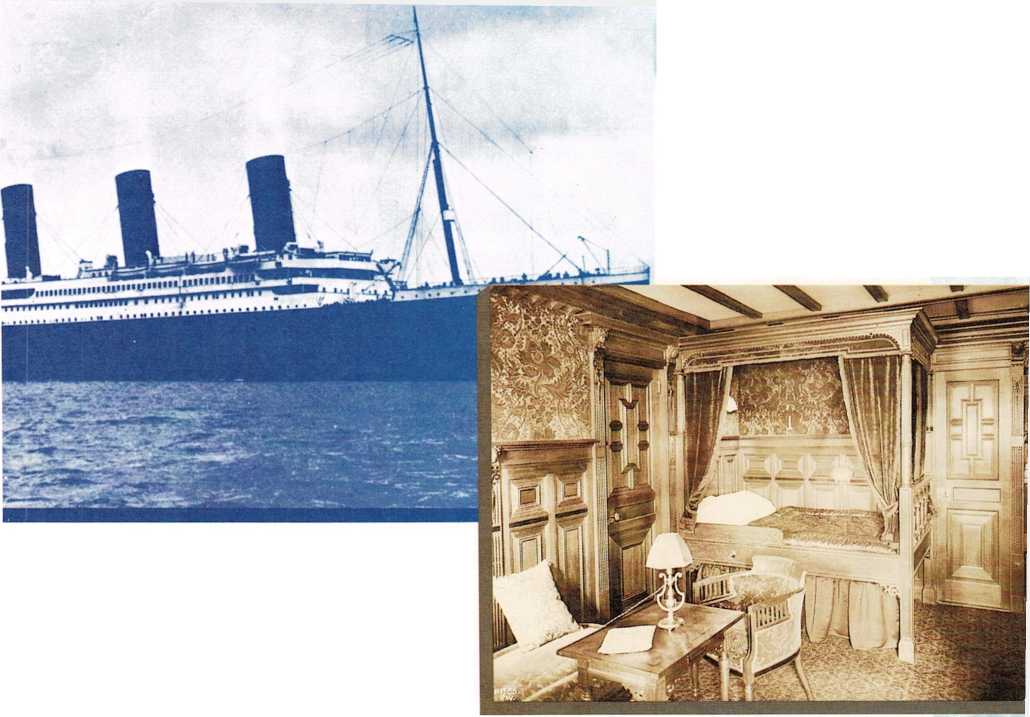

The ship was named Titanic, a word that means \”huge.” It was

well-named, for it was the largest ship in the world—882.5 feet (269

meters) long. It was the kind of ship known as a luxury liner, a kind of

floating hotel. It contained hundreds of beautiful rooms for passengers,

as well as game rooms, dining rooms, and a gymnasium.

The Titanic was a brand-new ship. In fact, this was her first voyage.

People said she was unsinkable. The builders had divided the lower part

of the ship into sixteen watertight compartments. Even if as many as

four of these should fill with water, the air in the others would keep

the ship afloat. \”God Himself could not sink this ship,” a member of

the crew had boasted before the Titanic sailed.

The Titanic was sailing from Southampton, England, to New York City.

All together, counting passengers and crew, there were more than two

thousand people aboard. As the brightly lighted ship sped through the

night,

This is the Titanic as it left England at the start of its

first—and only—voyage.

The Titanic was a luxury liner. It had hundreds of beautiful

passenger cabins like this one.

most of those on board were asleep in their cabins, confident of their

safety.

A little before midnight, a sailor on lookout duty sighted a large

iceberg in the ship’s path. He picked up the phone to the bridge, the

place from which the ship was steered.

\”Iceberg! Right ahead!”

At once, the officer on duty ordered the steersman to make a sharp turn.

For a moment, it seemed as if the ship must crash into the iceberg.

Then, at the last instant, the ship veered away. It passed the towering,

jagged mass of ice so closely that anyone standing on deck might have

reached out and touched it.

But as the Titanic slid past the iceberg, there was a faint grinding

noise. The ship seemed to shudder slightly.

Many passengers were awakened by the noise and the jar. Others, still

awake, heard the sound and felt the jar. Some went out on deck to see

what had happened.

The Titanic’s captain, a white-bearded man named Edward Smith, rushed

to the bridge from his cabin nearby. Quickly, he ordered men to check to

see what damage had been done. They found that the iceberg, hard as rock

and sharp as a knife, had sliced a gash three hundred feet (90 meters)

long in the ship’s bottom. Water was pouring into six compartments. The

men looked at one another in shock. There was no doubt—the Titanic

was going to sink!

The captain issued orders. The ship’s radio operator was told to send

out signals for help. Members of the crew hurried down the ship’s

corridors, waking passengers and helping them into life jackets. Most

people were a bit anxious, but there was no panic. They were not told

that the ship was going to sink— most of them wouldn’t have believed

it anyway.

The crew uncovered the lifeboats and made them ready. But there was a

terrible problem. There were only enough boats for about half the people

aboard.

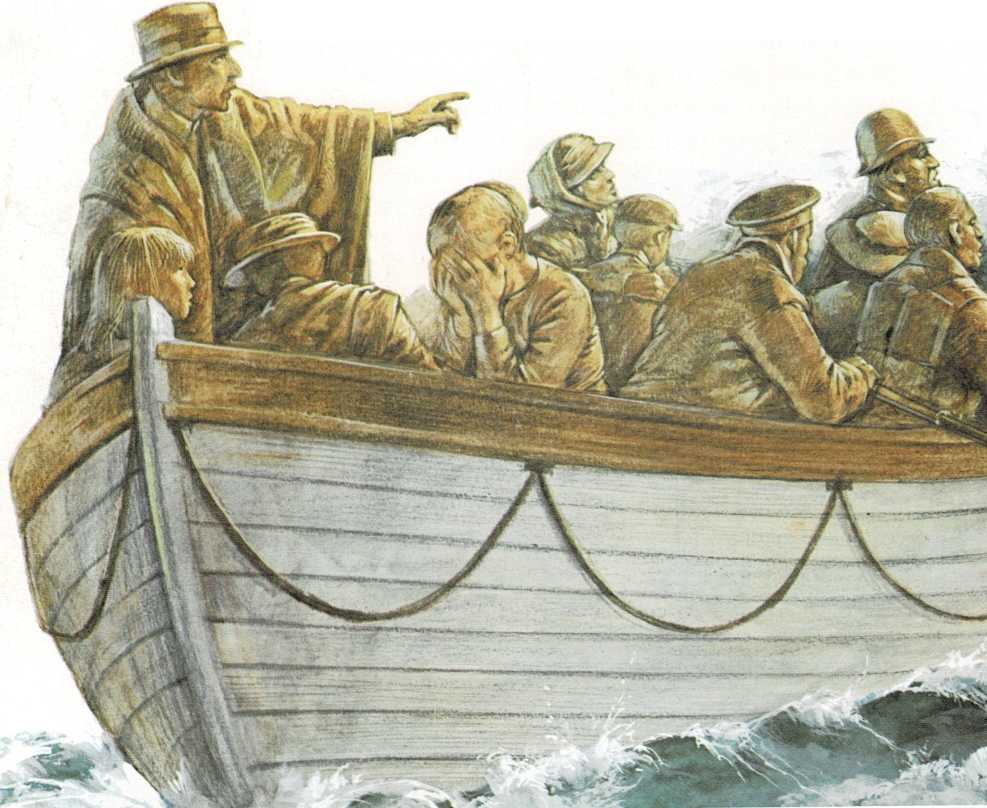

According to the law of the sea, women and children were put into the

lifeboats first. Husbands kissed their wives good-by, fathers kissed

their children. Many women refused to get into the boats, not wishing to

leave their husbands. Some men went, members of the crew and others who

could row the boats. Many people were left aboard, but they still

thought that everyone would be saved. Help was surely on the way. And

besides, the Titanic couldn’t really sink—could it?

As the lifeboats were lowered into the black, cold water, a ship was

seen on the horizon, less than twenty miles (32 kilometers) away. Help

was at hand! At once, signal rockets were fired. They streaked up into

the sky to explode with a bang and a flash of white stars.

But there was no reply from the other ship. Nor was there any response

to the distress signals sent out by radio. Months later, it was learned

that this ship, the Californian, had stopped for the night because of

the ice. Her radio operator, who had been on duty for more than fifteen

hours, went to bed only twenty minutes before the Titanic hit the

iceberg.

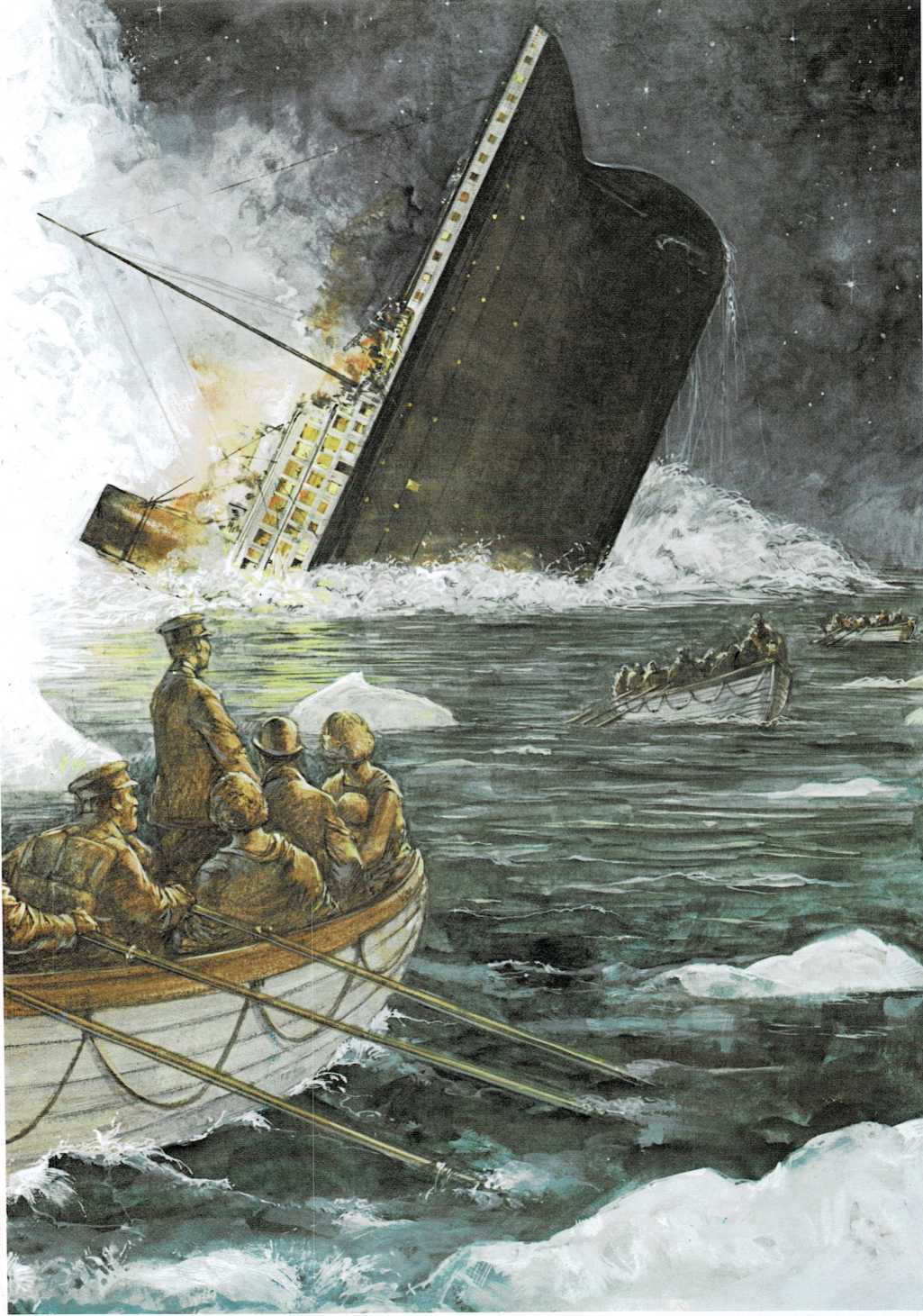

The lifeboats began to pull away from the Titanic. Everyone now knew

that the ship was indeed sinking. Its bow, or front, was much lower in

the water than the stern, or rear. Slowly, the stern rose into the air.

Many of the people left on board jumped into the icy water, hoping to

swim to a boat or find a piece of floating wreckage to which they could

cling.

Minutes dragged by while the people in the boats stared, unbelieving,

too shocked and stunned even to cry. The bow of the ship was now

underwater. The stern was lifting ever higher. The water around the

sinking ship was filled with floating objects—chairs, tables,

shuffleboard sticks . . . and people swimming for their lives.

Slowly, the Titanic’s, stern lifted until it was pointing straight up

at the sky. Then, gently, it sloped back and the ship slid beneath the

surface. With a last swirl, the water closed over the \”unsinkable”

ship.

A few—a very few—of those who had jumped overboard, or had been

washed

overboard as the ship went down, managed to reach a boat. Many people

were trapped on the sinking ship. Others died in the icy water.

From the time it grazed the iceberg, the Titanic had taken just two

hours and forty minutes to sink. Now, for more than another hour and a

half, the people in the boats fought to stay alive. It was bitter cold,

and many were only half dressed. Most were soaked to the skin. A few

died, of shock and cold.

Finally, at four o’clock in the morning, with the sun rising over a calm

sea dotted with floating icebergs, the ship Carpathia arrived. She had

steamed fifty-eight miles at top speed. Quickly, the frozen, stunned

survivors were taken aboard. There were only 705 of them. Some 1,500

people had died in the disaster— victims of the sea.