The “two-shelled” ones

The creature lay inside its boxlike shell, with the lid open. From under

the lid, a fringe of short, thin tentacles stuck out all around. Among

the tentacles gleamed many tiny, round, beautiful blue eyes—nearly a

hundred of them! The creature was feeding. As water flowed into its box,

it strained out the many tiny plants and animals floating in the water

and took them into its mouth.

The creature’s tiny eyes could not make out colors and shapes—only

light and shadows. Suddenly, some of the eyes saw a humped shadow that

was crawling slowly closer. And the creature’s sense of smell picked up

the odor of its terrible enemy, a starfish!

scallop

At once, the shell snapped shut. Then the creature made a series of hops

that carried it zigzagging off through the water. Some distance away, it

settled down again. It was out of danger for the moment.

The creature was the kind of mollusk we call a scallop

[(skahl]{.smallcaps} uhp). There are about three hundred different kinds

of scallops. They belong to the group of mollusks known as bivalves.

Bivalve means \”two valves.” All bivalves have two shells, and each

shell is called a valve. The top and bottom valves are connected by a

kind of hinge of muscle. Life for a bivalve is like living in a box.

A scallop’s shell is rounded. Usually, there are rows of ridges on it.

The shell may be a lovely shade of red, pale pink, or creamy yellow. The

creature got its name because the edges of the shell are wavy, or

scalloped.

The oyster is a cousin of the scallop. But, unlike a scallop, an oyster

can’t swim. The poor oyster is stuck where it is. When an oyster is very

young, it cements itself to one place and spends the rest of its life

there.

If danger threatens, an oyster can only protect itself by closing its

shell. Often, this does not help. A determined starfish can pull an

oyster’s shell open. And many-kinds of snails can simply drill right

through the shell.

An oyster’s body is just a grayish lump. It has many little feelers, but

no eyes and no way of smelling or hearing. It feeds in the same way a

scallop does. By waving tiny hairs on its gills, an oyster pulls tiny

water creatures in toward its funnel-shaped mouth.

Most oyster shells are rough and lumpy and not a bit pretty. But the

bivalves called pearl

oysters often make something that is very pretty—a pearl!

A pearl is formed when a grain of sand or other tiny object gets inside

an oyster’s shell.

This irritates the oyster. So, it begins to build a shell around the

object, just as it built its shell around itself.

The oyster slowly coats the object with the same smooth, shiny material

that lines the inside of its shell. As more and more of these coats are

built up, a round and beautiful pearl may be formed. Actually, all

bivalves can make pearls. But the best pearls, the ones used as jewels,

come only from pearl oysters.

The bivalves called clams lead a different sort of life from oysters and

scallops. A clam has a thick, muscular \”foot” that it can stick out of

its shell. With this foot, a clam can dig into the sand or mud to hide

itself.

There are many different kinds of clams, with differently shaped shells.

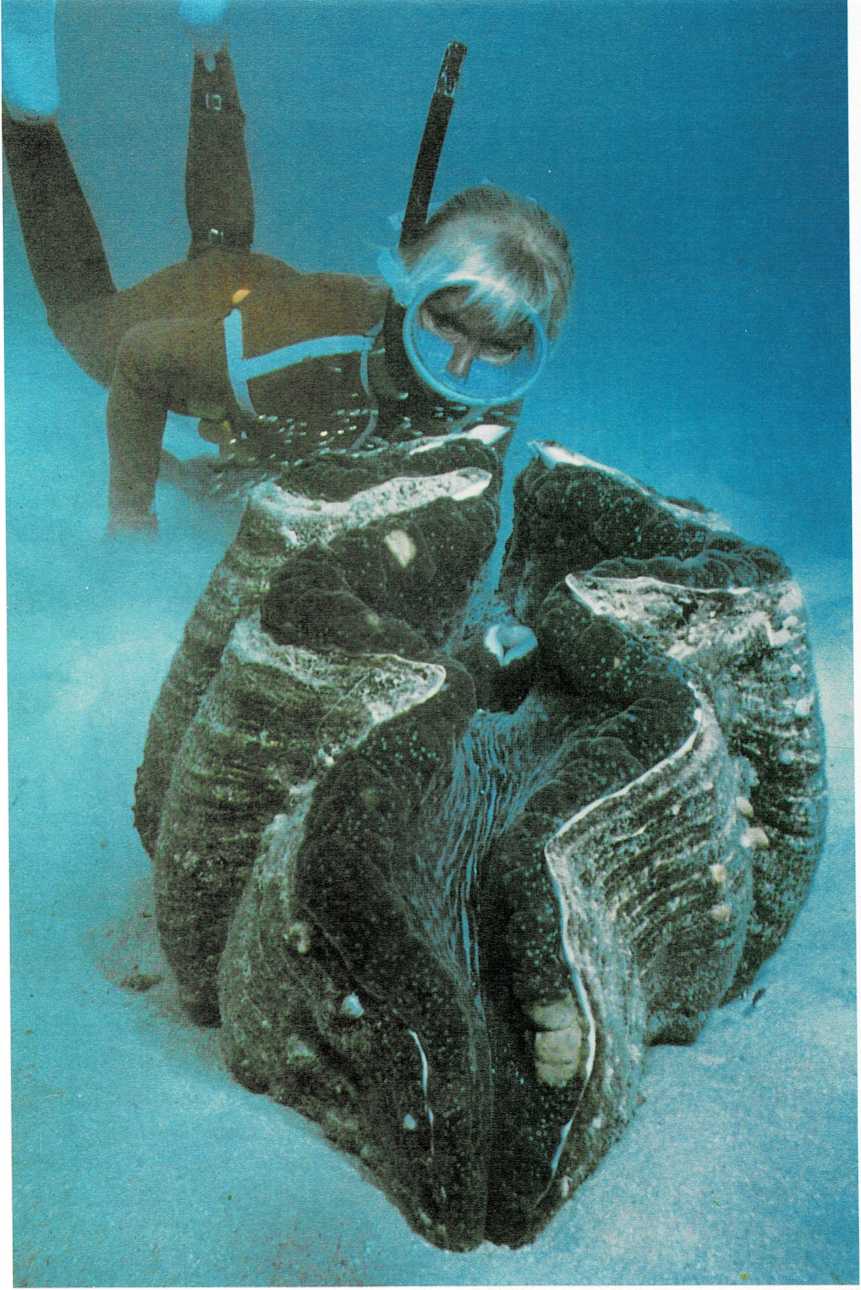

One kind is a giant! This giant clam lives in the Indian and Pacific

oceans. It often has a shell that is more than three feet (1 meter) long

and weighs as much as five hundred pounds (230 kg). Of course, these big

creatures can’t move or dig as small clams can. They simply sit, like

oysters, feeding on tiny creatures that float into their shells.

giant clam and diver