Stories

Thunder Butte

from When Thunders Spoke by Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve

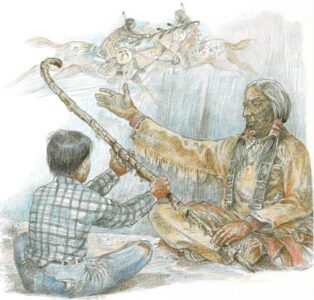

Fifteen-year-old Norman Two Bull is a modern Sioux boy who does not

accept the old Indian beliefs. One night he goes to his grandfather’s

tent, which is near Norman’s house on the Sioux reservation. Old Matt

Two Bull tells him that he has dreamed that if Norman would go to the

top of the Butte of Thunders—known to the Sioux as a Wakan, or holy

hill—good things will happen. But Norman must follow the old way—up

the south side and down the west side. When Norman agrees, his

grandfather gives him a strong willow cane to use as a probe and a

weapon. Early the next morning, Norman sets out. After a difficult

climb, he finally reaches the top of the butte.

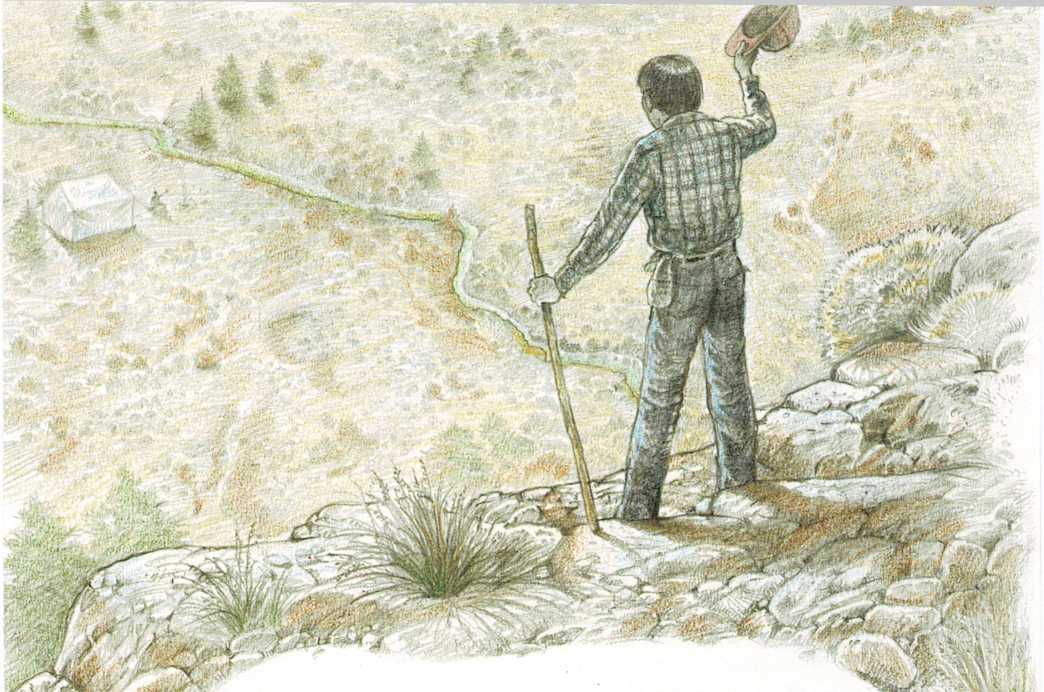

Norman gazed at a new world. The sun bathed the eastern valley in pale

yellow which was spotted with dark clumps of sage. The creek was a green

and silver serpent winding its way to the southeast. His grandfather’s

tent was a white shoe box in its clearing, and beside it stood a

diminutive form waving a red flag. It was Matt Two Bull signaling with

his shirt, and Norman knew that his grandfather had been watching him

climb. He waved his hat in reply and then walked to the outer edge of

the butte.^1^

The summit was not as smoothly flat as it looked from below. Norman

stepped warily over the many cracks and holes that pitted the surface.

He was elated that he had successfully made the difficult ascent, but

now as he surveyed the butte top he had a sense of discomfort.

There were burn scars on the rough summit, and Norman wondered if these

spots were where the lightning had struck, or were they evidence of

ancient man-made fires? He remembered that this was a sacred place to

the old ones and his uneasiness increased. He longed to be back on the

secure level of the plains.

On the west edge he saw that the butte cast a sharp shadow below because

the rim protruded as sharply as it had on the slope he’d climbed. Two

flat rocks jutted up on either side of a narrow opening, and Norman saw

shallow steps hewn into the space between. This must be the trail of

which his grandfather had spoken.

Norman stepped down and then quickly turned to hug the butte face as the

steps ended abruptly in space. The rest of the rocky staircase lay

broken and crumbled below. The only way down was to jump.

He cautiously let go of the willow branch and [^4]

watched how it landed and bounced against the rocks. He took a deep

breath as if to draw courage from the air. He lowered himself so that he

was hanging by his fingertips to the last rough step, closed his eyes

and dropped.

The impact of his landing stung the soles of his feet. He stumbled and

felt the cut of the sharp rocks against one knee as he struggled to

retain his balance. He did not fall and finally stood upright breathing

deeply until the wild pounding of his heart slowed. “Wow,” he said

softly as he looked back up at the ledge, “that must have been at least

a twenty-foot drop.”

He picked up the willow branch and started walking slowly down the steep

slope. The trail Matt Two Bull had told him about had been obliterated

by years of falling rock. Loose shale and gravel shifted under Norman’s

feet, and he probed cautiously ahead with the cane to test the firmness

of each step.

He soon found stones which he thought were agates. He identified them by

spitting on each rock and rubbing the wet spot with his finger. The dull

rock seemed to come alive! Variegated hues of brown and gray glowed as

if polished. They were agates all right. Quickly he had his salt bag

half full.

It was almost noon and his stomach growled. He stopped to rest against a

large boulder and pulled out his lunch from his shirt. But his mouth was

too dry to chew the cheese sandwich. He couldn’t swallow without water.

Thirsty and hungry, Norman decided to go straight down the butte and

head for home.

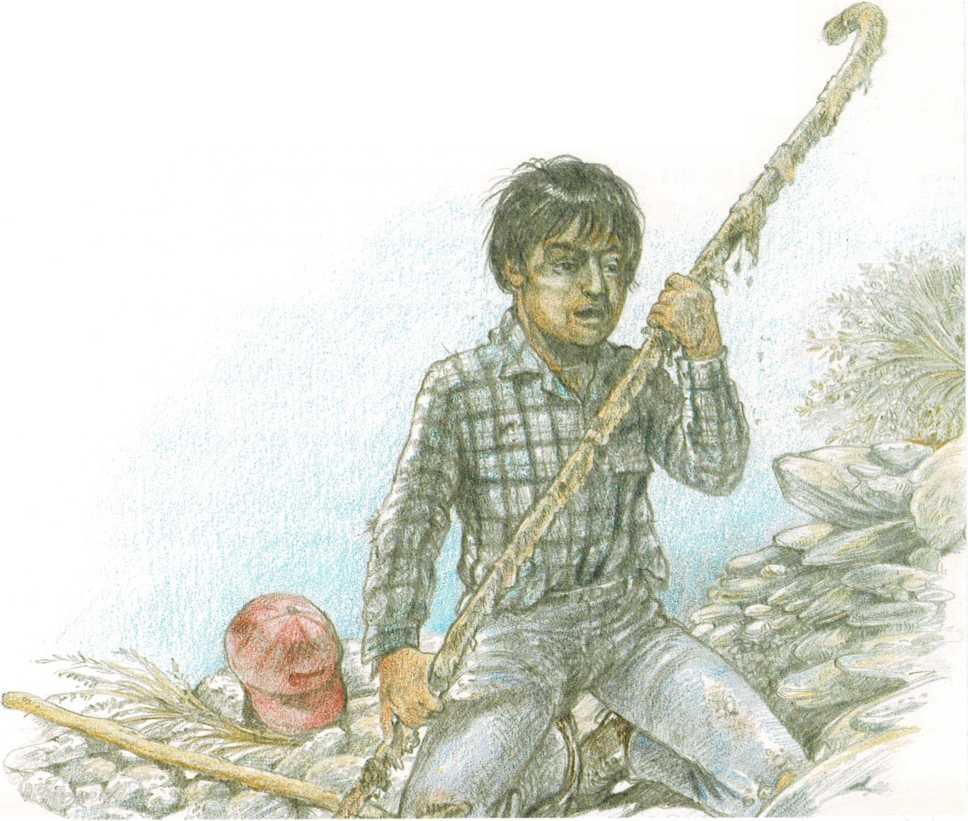

Walking more confidently as the slope leveled out he thrust the pointed

cane carelessly into the ground. He suddenly fell as the cane went deep

into the soft shale.

Norman slid several feet. Loose rocks rolled around him as he came to

rest against a boulder. He lay still for a long time fearing that his

tumble might cause a rock fall. But no thundering slide came, so he

cautiously climbed back to where the tip of the willow branch protruded

from the ground.

He was afraid that the cane may have plunged into a rattlesnake den.

Carefully he pulled out the stout branch, wiggling it this way and that

with one hand while he dug with the other. It came loose, sending a

shower of rocks down the hill, and Norman saw that something else was

sticking up in the hole he had uncovered.

Curious, and seeing no sign of snakes, he kept digging and soon found

the tip of a leather-covered stick. Bits of leather and wood fell off in

his hand as he gently pulled. The stick, almost as long as he was tall

and curved on one end, emerged as he tugged. Holding it before him, his

heart pounding with excitement, he realized that he had found a thing

that once belonged to the old ones.

Norman shivered at the thought that he may have disturbed a grave, which

was tehinda, forbidden. He

cleared more dirt away but saw no bones nor other sign that this was a

burial place. Quickly he picked up the stick and his willow cane and

hurried down the hill. When he reached the bottom he discovered that in

his fall the salt bag of agates had pulled loose from his belt. But he

did not return to search for it. It would take most of the afternoon to

travel around the base of the butte to the east side.

The creek was in the deep shade of the butte when he reached it and

thirstily flopped down and drank. He crossed the shallow stream and

walked to his grandfather’s tent.

“You have been gone a long time,” Matt Two Bull greeted as Norman walked

into the clearing where the old man was seated.

“I have come from the west side of the butte, Grandpa,” Norman said

wearily. He sat down on the ground and examined a tear in his jeans and

the bruise on his knee.

“Was it difficult?” the old man asked.

“Yes,” Norman nodded. He told of the rough climb up the south slope, the

jump down and finally of his fall which led him to discover the long

leather-covered stick. He held the stick out to his grandfather who took

it and examined it carefully.

“Are you sure there was no body in the place where you found this?”

Norman shook his head. “No, I found nothing else but the stick. Do you

know what it is, Grandpa?”

“You have found a coup stick which belonged to the old ones.”

“I know that it is old because the wood is brittle and the leather is

peeling, but what is—was a coup stick?” Norman asked.

“In the days when the old ones roamed all of the plains,” the old man

swept his hand in a circle, “a courageous act of valor was thought to be

more

important than killing an enemy. When a warrior rode or ran up to his

enemy, close enough to touch the man with a stick, without killing or

being killed, the action was called coup.

“The French, the first white men in this part of the land, named this

brave deed coup. In their language the word meant ‘hit’ or ‘strike.’

The special stick which was used to strike with came to be known as a

coup stick.

“Some sticks were long like this one,” Matt Two Bull held the stick

upright. “Some were straight, and others had a curve on the end like the

sheep herder’s crook,” he pointed to the curving end of the stick.

“The sticks were decorated with fur or painted leather strips. A warrior

kept count of his coups by tying an eagle feather to the crook for

each brave deed. See,” he pointed to the staff end, “here is a remnant

of a tie thong which must have once held a feather.”

The old man and boy closely examined the coup stick. Matt Two Bull

traced with his finger the faint zig zag design painted on the stick.

“See,” he said, “it is the thunderbolt.”

“What does that mean?” Norman asked.

“The Thunders favored a certain few of the young men who sought their

vision on the butte. The thunderbolt may have been part of a sacred

dream sent as a token of the Thunders’ favor. If this was so, the young

man could use the thunderbolt symbol on his possessions.”

“How do you suppose the stick came to be on the butte?” Norman asked.

His grandfather shook his head. “No one can say. Usually such a thing

was buried with a dead warrior as were his weapons and other prized

belongings.”

“Is the coup stick what you dreamed about, Grandpa?”

“No. In my dream I only knew that you were to find a Wakan, a holy

thing. But I did not know what it would be.”

Norman laughed nervously. “What do you mean, Wakan? Is this stick

haunted?”

Matt Two Bull smiled, “No, not like you mean in a fearful way. But in a

sacred manner because it once had great meaning to the old ones.”

“But why should I have been the one to find it?” Norman questioned.

His grandfather shrugged, “Perhaps to help you understand the ways—the

values of the old ones.”

“But nobody believes in that kind of thing anymore,” Norman scoffed.

“And even if people did, I couldn’t run out and hit my enemy with the

stick and get away with it.” He smiled thinking of Mr. Brannon. “No one

would think 1 was brave. I’d probably just get thrown in jail.”

Suddenly Norman felt compelled to stop talking. In the distance he heard

a gentle rumble which seemed to come from the butte. He glanced up at

the hill looming high above and saw that it was capped with dark,

low-hanging clouds.

Matt Two Bull looked too and smiled. “The Thunders are displeased with

your thoughts,” he said to Norman. “Listen to their message.”

A sharp streak of lightning split the clouds and the thunder cracked and

echoed over the plains.

Norman was frightened but he answered with bravado, “The message I get

is that a storm is coming,” but his voice betrayed him by quavering.

“Maybe you’d better come home with me, Grandpa. Your tent will be soaked

through if it rains hard.”

“No,” murmured Matt Two Bull, “no rain will come. It is just the

Thunders speaking.” There was another spark of lightning, and an

explosive reverberation sounded as if in agreement with the old man.

Norman jumped to his feet. “Well, I’m going home. Mom will be worried

because I’m late now.” He turned to leave.

“Wait!” Matt Two Bull commanded. “Take the coup stick with you.”

Norman backed away, “No, I don’t want it. You can have it.”

The old man rose swiftly despite the stiffness of his years and sternly

held out the stick to the boy. “You found it. It belongs to you. Take

it!”

Norman slowly reached out his hands and took the stick.

“Even if you think the old ways are only superstition and the stick no

longer has meaning, it is all that remains of an old life and must be

treated with respect.” Matt Two Bull smiled at the boy. “Take it,” he

repeated gently, “and hang it in the house where it will not be

handled.”

Norman hurried home as fast as he could carrying the long stick in one

hand and the willow cane in the other. He felt vaguely uneasy and

somehow a little frightened. It was only when he reached the security of

his home that he realized the thunder had stopped and there had been no

storm.

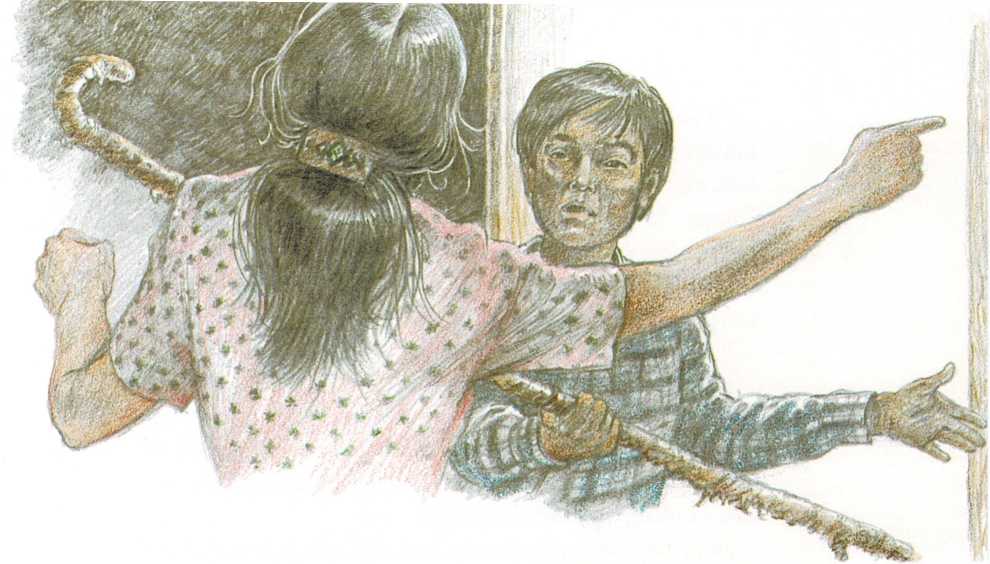

“Mom,” he called as he went into the house, “I’m home.”

His mother was standing at the stove. “Oh, Norman,” she greeted him

smiling. “I’m glad you’re back. I was beginning to worry.” Her welcoming

smile turned to a frown as she saw the coup stick in Norman’s hand.

“What is that?”

“Grandpa says it’s a coup stick. Here,” Norman handed it to her, “take

a look at it. It’s interesting the way it is made and decor—“

“No,” Sarah interrupted and backed away from him. “I won’t touch that

heathen thing no matter what it is! Get it out of the house!”

“What?” Norman asked, surprised and puzzled.

“There is nothing wrong with it. It’s just an old stick I found up on

the butte.”

“I don’t care,” Sarah insisted. “I won’t have such a thing in the

house!”

“But, Mom,” Norman protested, “it’s not like we believe in those old

ways the way Grandpa does.”

But Sarah was adamant. “Take it out of the house!”

she ordered, pointing to the door. “We’ll talk about it when your dad

gets home.”

Reluctantly Norman took the coup stick outside and gently propped it

against the house and sat on the steps to wait for his father. He was

confused. First by his grandfather’s reverent treatment of the coup

stick as if it were a sacred object and then by Sarah’s rejection of it

as a heathen symbol.

He looked at the stick where it leaned against the wall and shook his

head. So much fuss over a brittle, rotten length of wood. Even though he

had gone through a lot of hard, even dangerous, effort to get it he was

now tempted to heave it out on the trash pile.

Norman wearily leaned his head against the house. He suddenly felt tired

and his knee ached. As he sat wearily rubbing the bruise John Two Bull

rode the old mare into the yard. Norman got up and walked back to the

shed to help unsaddle the horse.

John climbed stiffly out of the saddle. His faded blue work shirt and

jeans were stained with perspiration and dirt. His boots were worn and

scuffed.

“Hard day, Dad?” Norman asked.

“Yeah,” John answered, slipping the bridle over the mare’s head.

“Rustlers got away with twenty steers last night. I spent the day

counting head and mending fences. Whoever the thief was cut the fence,

drove a truck right onto the range and loaded the cattle without being

seen.” He began rubbing the mare down as she munched the hay in her

manger.

“How did your day on the butte go?” John asked.

“Rough,” Norman answered. “I’m beat too. The climb up the butte was

tough and coming down was bad too.” He told his father all that had

happened on the butte, winding up with the climax of his falling and

finding the old coup stick.

John listened attentively and did not interrupt until Norman told of

Matt Two Bull’s reaction to the stick. “I think Grandpa’s mind has

gotten weak,” Norman said. “He really believes that the coup stick has

some sort of mysterious power and that the Thunders were talking.”

“Don’t make fun of your grandfather,” John reprimanded, “or of the old

ways he believes in.”

“Okay, okay,” Norman said quickly, not wanting another scolding. “But

Mom is just the opposite from Grandpa,” he went on. “She doesn’t want

the coup stick in the house. Says it’s heathen.”

He walked to the house and handed the stick to his father. John examined

it and then carried it into the house.

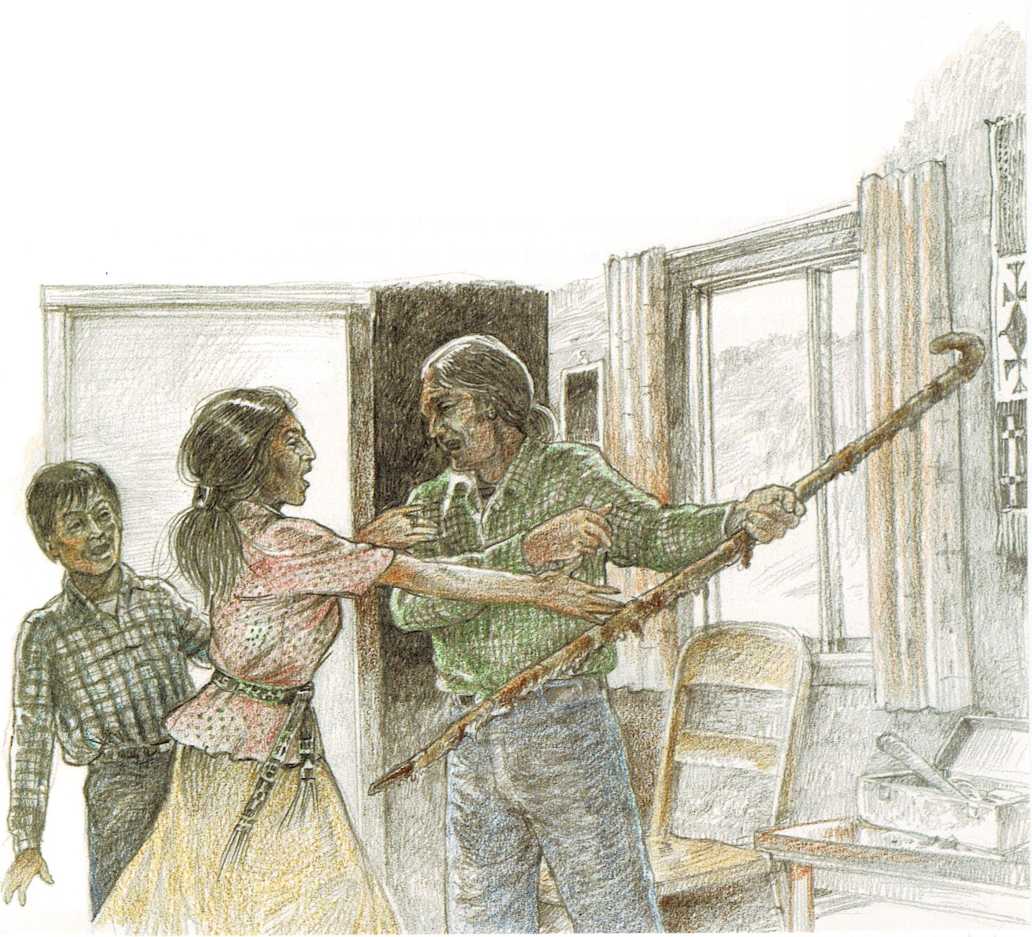

“John!” Sarah exclaimed as she saw her husband bring the stick into the

room. “I told Norman, and I tell you, that I won’t have that heathenish

thing in the house!”

But John ignored her and propped the stick against the door while he

pulled his tool box out from under the washstand to look for a hammer

and nails.

“John,” Sarah persisted, “did you hear me?”

“I heard,” John answered quietly, but Norman knew

his father was angry. “And I don’t want to hear anymore.”

Norman was surprised to hear his father speak in such a fashion. John

was slow to anger, usually spoke quietly and tried to avoid conflict of

any kind, but now he went on.

“This,” he said holding the coup stick upright, “is a relic of our

people’s past glory when it was a good thing to be an Indian. It is a

symbol of something that shall never be again.”

Sarah gasped and stepped in front of her husband as he started to climb

a chair to pound the nails in the wall above the window. “But that’s

what I mean,” she said. “Those old ways were just superstition. They

don’t mean anything now—they can’t because such a way of life can’t be

anymore. We don’t need to have those old symbols of heathen ways hanging

in the house!” She grabbed at the coup stick, but John jerked it out

of her reach.

“Don’t touch it!” he shouted and Sarah fell back against the table in

shocked surprise. Norman took a step forward as if to protect his

mother. The boy had never seen his father so angry.

John shook his head as if to clear it. “Sarah, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean

to yell. It’s just that the old ones would not permit a woman to touch

such a thing as this.” He handed Norman the stick to hold while he

hammered the nails in the wall. Then he hung the stick above the window.

“Sarah,” he said as he put the tools away, “think of the stick as an

object that could be in a museum, a part of history. It’s not like we

were going to fall down on our knees and pray to it.” His voice was

light and teasing as he tried to make peace.

But Sarah stood stiffly at the stove preparing supper and would not

answer. Norman felt sick. His appetite was gone. When his mother set a

plate of food before him he excused himself saying, “I guess I’m too

tired to eat,” and went to his room.

But after he had undressed and crawled into bed he couldn’t sleep. His

mind whirled with the angry words his parents had spoken. They had never

argued in such a way before. “I wish I had never brought that old stick

home,” he whispered and then pulled the pillow over his head to shut out

the sound of the low rumble of thunder that came from the west.

[5ye]{.smallcaps}

Old Matt Two Bull dreamed of good things happening if Norman climbed the

butte. But the first thing the old coup stick brings is a family

argument. You can find out what happens next by reading When Thunders

Spoke. The author, Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve, who spent her childhood

on a Sioux reservation, has written other books about the American

Indians, including Betrayed, High Elk’s Treasure, and *Jimmy Yellow

Hawk.