The Living Kuan-yin

a Chinese folk tale

from Sweet and Sour: Tales from China by Carol Kendall and Yao-wen Li

Even though the family name of Chin means gold, it does not signify

that everyone of that name is rich. Long ago, in the province of

Chekiang, however, there was a certain wealthy Chin family of whom it

was popularly said that its fortune was as great as its name. It seemed

quite fitting, then, when a son was born to the family, that he should

be called Po-wan, “Million,” for he was certain to be worth a million

pieces of gold when he came of age.

With such a happy circumstance of names, Po-wan himself never doubted

that he would have a never-ending supply of money chinking through his

fingers, and he spent it accordingly—not on himself, but on any

unfortunate who came to his attention. He had a deep sense of compassion

for anyone in distress of body or spirit: a poor man had only to hold

out his hand, and Po-wan poured gold into it; if a destitute

The Living Kuan-yin

widow and her brood of starvelings but lifted sorrowful eyes to his, he

provided them with food and lodging and friendship for the rest of their

days.

In such wise did he live that even a million gold pieces were not enough

to support him. His resources so dwindled that finally he scarcely had

enough food for himself; his clothes flapped threadbare on his wasted

frame; and the cold seeped into his bone marrow for lack of a fire.

Still he gave away the little money that came to him.

One day, as he scraped out half of his bowl of rice for a beggar even

hungrier than he, he began to ponder on his destitute state.

“Why am I so poor?” he wondered. “I have never spent extravagantly. I

have never, from the day of my birth, done an evil deed. Why then am I,

whose very name is A Million Pieces of Gold, no longer able to find even

a copper to give this unfortunate creature, and have only a bowl of rice

to share with him?”

He thought long about his situation and at last determined to go without

delay to the South Sea. Therein, it was told, dwelt the all-merciful

goddess, the Living Kuan-yin, who could tell the past and future. He

would put his question to her and she would tell him the answer.

Soon he had left his home country behind and travelled for many weeks in

unfamiliar lands. One day he found his way barred by a wide and

furiously flowing river. As he stood first on one foot and then on the

other, wondering how he could possibly get across, he heard a commanding

voice calling from the top of an overhanging cliff.

“Chin Po-wan!” the voice said, “if you are going to the South Sea,

please ask the Living Kuan-yin a question for me!”

“Yes, yes, of course,” Po-wan agreed at once, for he had never in his

life refused a request made of him. In

any case, the Living Kuan-yin permitted each person who approached her

three questions, and he had but one of his own to ask.

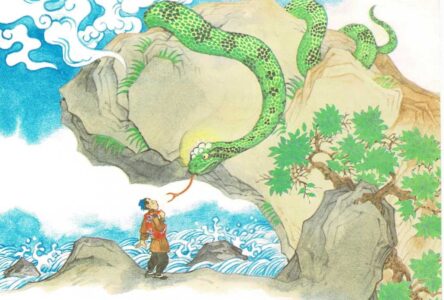

Craning his head towards the voice coming from above, he suddenly began

to tremble, for the speaker was a gigantic snake with a body as large as

a temple column. Po-wan was glad he had agreed so readily to the

request.

“Ask her then,” said the snake, “why I am not yet a dragon even though I

have practiced self-denial for more than one thousand years?”

“That I will do, and gl-gladly,” stammered Po-wan, hoping that the snake

would continue to practice self-denial just a bit longer. “But, your .

.. your Snakery … or your Serpentry, perhaps I should say … that

is … you see, don’t you … first I must cross this raging river,

and I know not how.”

“That is no problem, at all,” said the snake. “I shall carry you across,

of course.”

“Of course,” Po-wan echoed weakly. Overcoming his fear and his

reluctance to touch the slippery-slithery scales, Chin Po-wan climbed on

to the snake’s back and rode across quite safely. Politely, and just a

bit hurriedly, he thanked the self-denying serpent and bade him goodbye.

Then he continued on his way to the South Sea.

By noon he was very hungry. Fortunately a nearby inn offered meals at a

price he could afford. While waiting for his bowl of rice, he chatted

with the innkeeper and told him of the Snake of the Cliff, which the

innkeeper knew well and respected, for the serpent always denied bandits

the crossing of the river. Inadvertently, during the exchange of

stories, Po-wan revealed the purpose of his journey.

“Why then,” cried the innkeeper, “let me prevail upon your generosity to

ask a word for me.” He laid an appealing hand on Po-wan’s ragged sleeve.

“I have a beautiful daughter,” he said, “wonderfully amiable and

pleasing of disposition. But although she is in her twentieth year, she

has never in all her life uttered a single word. I should be very much

obliged if you would ask the Living Kuan-yin why she is unable to

speak.”

Po-wan, much moved by the innkeeper’s plea for his mute daughter, of

course promised to do so. For after all, the Living Kuan-yin allowed

each person three questions and he had but one of his own to ask.

Nightfall found him far from any inn, but there were houses in the

neighbourhood, and he asked for lodging at the largest. The owner, a man

obviously of great wealth, was pleased to offer him a bed in a fine

chamber, but first begged him to partake of a hot meal and good drink.

Po-wan ate well, slept soundly, and, much refreshed, was about to depart

the following morning, when his good host, having learned that Po-wan

was journeying to the South Sea, asked if he

would be kind enough to put a question for him to the Living Kuan-yin.

“For twenty years,” he said, “from the time this house was built, my

garden has been cultivated with the utmost care, yet in all those years,

not one tree, not one small plant, has bloomed or borne fruit, and

because of this, no bird comes to sing nor bee to gather nectar. I don’t

like to put you to a bother, Chin Po-wan, but as you are going to the

South Sea anyway, perhaps you would not mind seeking out the Living

Kuan-yin and asking her why the plants in my garden don’t bloom?”

“I shall be delighted to put the question to her,” said Po-wan. For

after all, the Living Kuan-yin allowed each person three questions, and

he had but…

Travelling onward, Po-wan examined the quandary in which he found

himself. The Living Kuan-yin allowed but three questions, and he had

somehow, without quite knowing how, accumulated four questions. One of

them, would have to go unasked, but which? If he left out his own

question, his whole journey would have been in vain. If, on the other

hand, he left out the question of the snake, or the innkeeper, or the

kind host, he would break his promise and betray their faith in him.

“A promise should never be made if it cannot be kept,” he told himself.

“I made the promises and therefore I must keep them. Besides, the

journey will not be in vain, for at least some of these problems will be

solved by the Living Kuan-yin. Furthermore, assisting others must

certainly be counted as a good deed, and the more good deeds abroad in

the land, the better for everyone, including me.”

At last he came into the presence of the Living Kuan-yin.

First, he asked the serpent’s question: “Why is the Snake of the Cliff

not yet a dragon, although he has

practised self-denial for more than one thousand years?”

And the Kuan-yin answered: “On his head are seven bright pearls. If he

removes six of them, he can become a dragon.”

Next, Po-wan asked the innkeeper’s question: “Why is the innkeeper’s

daughter unable to speak, although she is in the twentieth year of her

life?”

And the Living Kuan-yin answered: “It is her fate to remain mute until

she sees the man destined to be her husband.”

Last, Po-wan asked the kind host’s question: “Why are there never

blossoms in the rich man’s garden, although it has been carefully

cultivated for twenty years?”

And the Living Kuan-yin answered: “Buried in the garden are seven big

jars filled with silver and gold. The flowers will bloom if the owner

will rid himself of half the treasure.”

Then Chin Po-wan thanked the Living Kuan-yin and bade her good-bye.

On his return journey, he stopped first at the rich man’s house to give

him the Living Kuan-yin’s answer. In gratitude the rich man gave him

half the buried treasure.

Next Po-wan went to the inn. As he approached, the innkeeper’s daughter

saw him from the window and called, “Chin Po-wan! Back already! What did

the Living Kuan-yin say?”

Upon hearing his daughter speak at long last, the joyful innkeeper gave

her in marriage to Chin Po-wan.

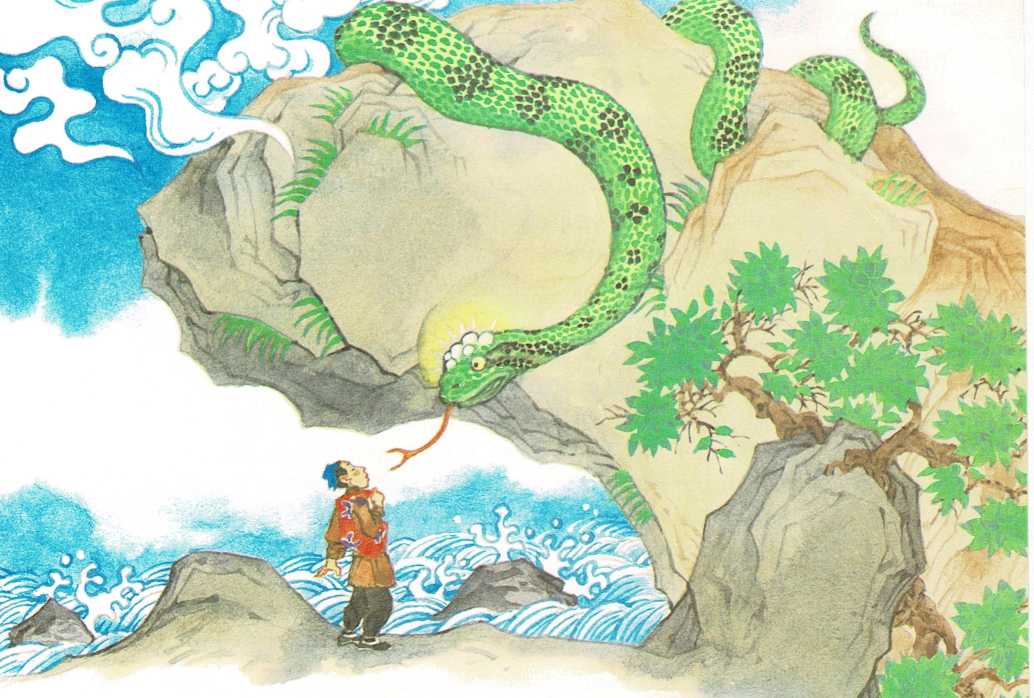

Lastly, Po-wan went to the cliffs by the furiously flowing river to tell

the snake what the Living Kuan-yin had said. The grateful snake

immediately gave him six of the bright pearls and promptly turned into a

magnificent dragon, the remaining pearl in his forehead lighting the

headland like a great beacon.

And so it was that Chin Po-wan, that generous and good man, was once

more worth a million pieces of gold.

5?S

Did you like this tale? If so, there are many others like it waiting for

you in Sweet and Sour: Tales from China, which is a choice collection

of charming Chinese folk tales. And if you look in the folklore section

of your library, you will find hundreds of other books filled with tales

from many lands.