\

Stories

The Homecoming

from Sounder

by William H. Armstrong

Sounder, a fine coon dog, was shot when the sheriff arrested his master.

His wounds have healed, but he is badly crippled. With the care of the

boy—his master’s son—and the boy’s mother, he has lived for many

years. But he can’t forget his master, who has never returned.

Late one August afternoon the boy and his mother sat on the shaded

corner of the porch. The heat and drought of dog days had parched the

earth, and the crops had been laid by. The boy had come home early

because there was nothing to do in the fields.

“Dog days is a terrible time,” the woman said. “It’s when the heat is so

bad the dogs go mad.” The boy would not tell her that the teacher had

told him that

dog days got their name from the Dog Star because it rose and set with

the sun during that period. She had her own feeling for the earth, he

thought, and he would not confuse it.

“It sure is hot,” he said instead. “Lucky to come from the fields

early.” He watched the heat waves as they made the earth look like it

was moving in little ripples.

Sounder came around the corner of the cabin from somewhere, hobbled back

and forth as far as the road several times, and then went to his cool

spot under the porch. “That’s what I say about dog days,” the woman

said. “Poor creature’s been addled with the heat for three days. Can’t

find no place to quiet down. Been down the road nearly out o’ sight a

second time today, and now he musta come from the fencerows. Whines all

the time. A mad dog is a fearful sight. Slobberin’ at the mouth and

runnin’ every which way ’cause they’re blind. Have to shoot ’em ‘fore

they bite some child. It’s awful hard.”

“Sounder won’t go mad,” the boy said. “He’s lookin’ for a cooler spot, I

reckon.”

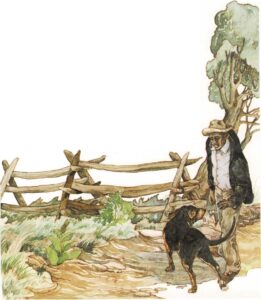

A lone figure came on the landscape as a speck and slowly grew into a

ripply form through the heat waves. “Scorchin’ to be walkin’ and totin’

far today,” she said as she pointed to the figure on the road.

A catbird fussed in the wilted lilac at the corner of the cabin. “Why’s

that bird fussin’ when no cat’s prowlin’? Old folks has a sayin’ that if

a catbird fusses ’bout nothin’, somethin’ bad is cornin’. It’s a bad

sign.”

“Sounder, I reckon,” the boy said. “He just passed her bush when he came

around the cabin.”

In the tall locust at the edge of the fence, its top leaves yellowed

from lack of water, a mockingbird mimicked the catbird with half a dozen

notes, decided it was too hot to sing, and disappeared. The great coon

dog, whose rhythmic panting came through the porch floor, came from

under the house and began to whine.

As the figure on the road drew near, it took shape and grew indistinct

again in the wavering heat. Sometimes it seemed to be a person dragging

something, for little puffs of red dust rose in sulfurous clouds at

every other step. Once or twice they thought it might be a brown cow or

mule, dragging its hooves in the sand and raising and lowering its weary

head.

Sounder panted faster, wagged his tail, whined, moved from the dooryard

to the porch and back to the dooryard.

The figure came closer. Now it appeared to be a child carrying something

on its back and limping.

“The children still at the creek?” she asked.

“Yes, but it’s about dry.”

Suddenly the voice of the great coon hound broke the sultry August

deadness. The dog dashed along the road, leaving three-pointed clouds of

red dust to settle back to earth behind him. The mighty voice rolled out

upon the valley, each flutelike bark echoing from slope to slope.

“Lord’s mercy! Dog days done made him mad.” And the rocker was still.

Sounder was a young dog again. His voice was the same mellow sound that

had ridden the November breeze from the lowlands to the hills. The boy

and his mother looked at each other. The catbird stopped her fussing in

the wilted lilac bush. On three legs, the dog moved with the same

lightning speed that had carried him to the throat of a grounded

raccoon.

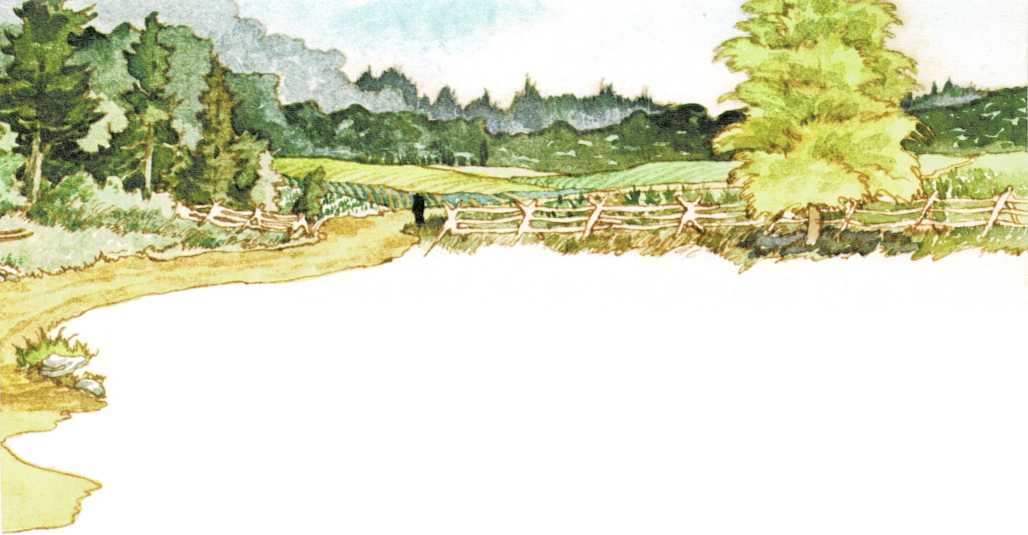

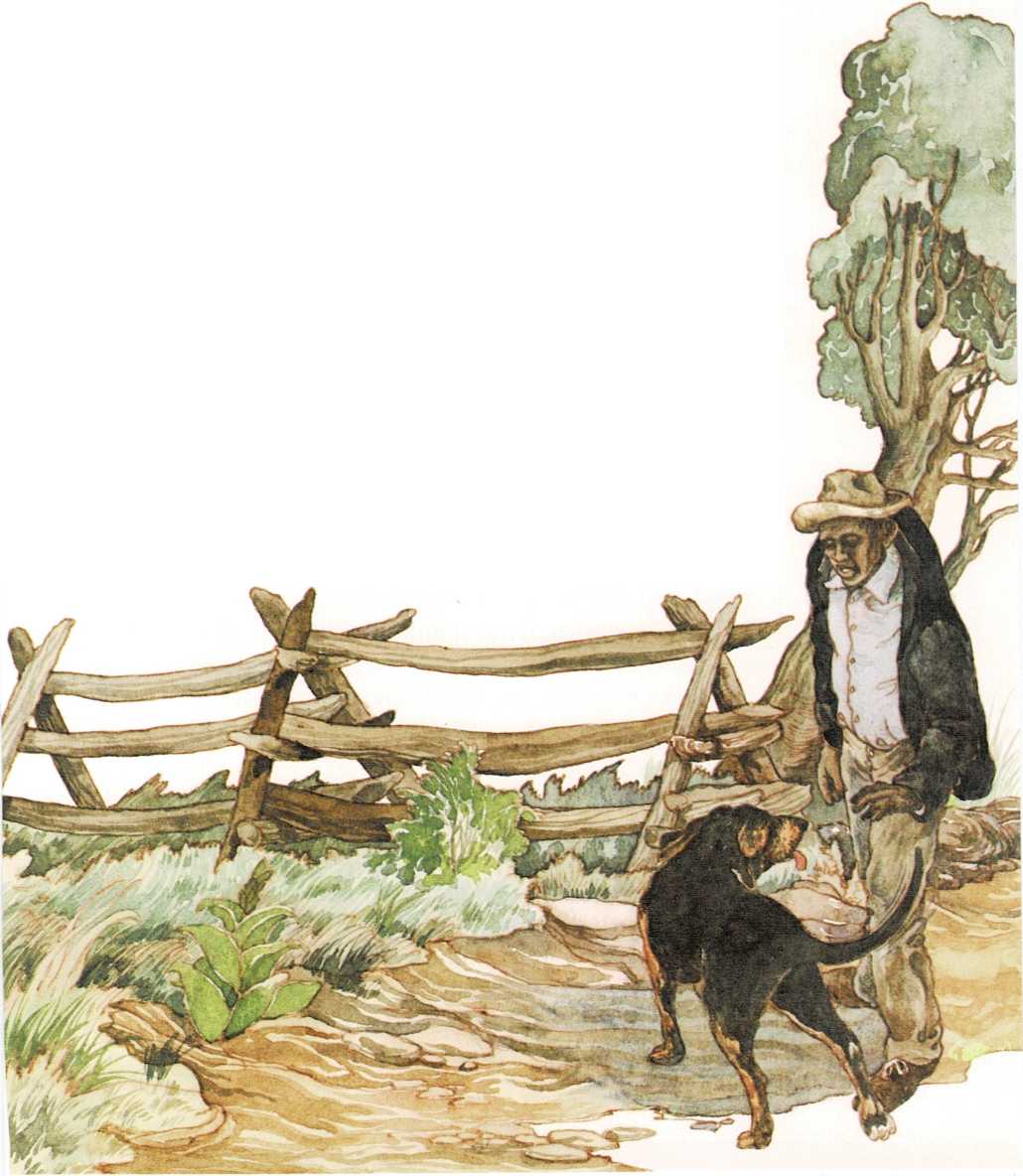

Sounder’s master had come home. Taking what might have been measured as

a halting half step and

then pulling a stiff, dead leg forward, dragging a foot turned sideways

in the dust, the man limped into the yard. Sounder seemed to understand

that to jump up and put his paw against his master’s breast would topple

him into the dust, so the great dog smelled and

whined and wagged his tail and licked the limp hand dangling at his

master’s side. He hopped wildly around his master in a circle that

almost brought head and tail together.

The head of the man was pulled to the side where a limp arm dangled and

where the foot pointed outward as it was dragged through the dust. What

had been a shoulder was now pushed up and back to make a one-sided hump

so high that the leaning head seemed to rest upon it. The mouth was

askew too, and the voice came out of the part farthest away from the

withered, wrinkled, lifeless side.

The woman in the still rocker said, “Lord, Lord,” and sat suffocated in

shock.

“Sounder knew it was you just like you was cornin’ home from work,” the

boy said in a clear voice.

Half the voice of the man was gone too, so in slow,

measured, stuttering he told how he had been caught in a dynamite blast

in the prison quarry, how the dead side had been crushed under an

avalanche of limestone, and how he had been missed for a whole night in

the search for dead and wounded. He told how the pain of the crushing

stone had stopped in the night, how doctors had pushed and pulled and

encased the numb side of his body in a cast, how they had spoken kindly

to him and told him he would die. But he resolved he would not die, even

with a half-dead body, because he wanted to come home again.

“For being hurt, they let me have time off my sentence,” the man said,

“and since I couldn’t work, I guess they was glad to.”

“The Lord has brought you home,” the woman said.

The boy heard faint laughter somewhere behind the cabin. The children

were coming home from the creek. He went around the cabin slowly, then

hurried to meet them.

“Pa’s home,” he said and grabbed his sister, who had started to run

toward the cabin. “Wait. He’s mighty crippled up, so behave like nothin’

has happened.”

“Can he walk?” the youngest child asked.

“Yes! And don’t you ask no questions.”

“You been mighty natural and considerate,” the mother said to the

younger children later when she went to the woodpile and called them to

pick dry kindling for a quick fire. When she came back to the porch she

said, “We was gonna just have a cold piece ’cause it’s so sultry, but

now I think I’ll cook.” Everything don’t change much, the boy thought.

There’s eatin’ and sleepin’ and talkin’ and settin’ that goes on. One

day might be different from another, but there ain’t much difference

when they’re put together.

Sometimes there were long quiet spells. Once or twice the boy’s mother

said to the boy, “He’s powerful proud of your learnin’. Read somethin’

from the

Scriptures.” But mostly they just talked about heat and cold, and wind

and clouds, and what’s gonna be done, and time passing.

As the days of August passed and September brought signs of autumn, the

crippled man sat on the porch step and leaned the paralyzed, deformed

side of his body against a porch post. This was the only comfortable

sitting position he could find. The old coon dog would lie facing his

master, with his one eye fixed and his one ear raised. Sometimes he

would tap his tail against the earth. Sometimes the ear would droop and

the eye would close. Then the great muscles would flex in dreams of the

hunt, and the mighty chest would give off a muffled whisper of a bark.

Sometimes the two limped together to the edge of the fields, or wandered

off into the pine woods. They never went along the road. Perhaps they

knew how strange a picture they made when they walked together.

About the middle of September the boy left to go back to his teacher.

“It’s the most important thing,” his mother said.

And the crippled man said, “We’re fine. We won’t need nothin’.”

“I’ll come for a few days before it’s cold to help gather wood and

walnuts.”

The broken body of the old man withered more and more, but when the

smell of harvest and the hunt came with October, his spirit seemed to

quicken his dragging step. One day he cleaned the dusty lantern globe,

and the old dog, remembering, bounced on his three legs and wagged his

tail as if to say “I’m ready.”

The boy had come home. To gather the felled trees and chop the standing

dead ones was part of the field pay too. He had been cutting and

dragging timber all day.

Sometimes he had looked longingly at the lantern and possum sack, but

something inside him had said

“Wait. Wait and go together.” But the boy did not want to go hunting

anymore. And without his saying anything, his father had said, “You’re

too tired, child. We ain’t goin’ far, no way.”

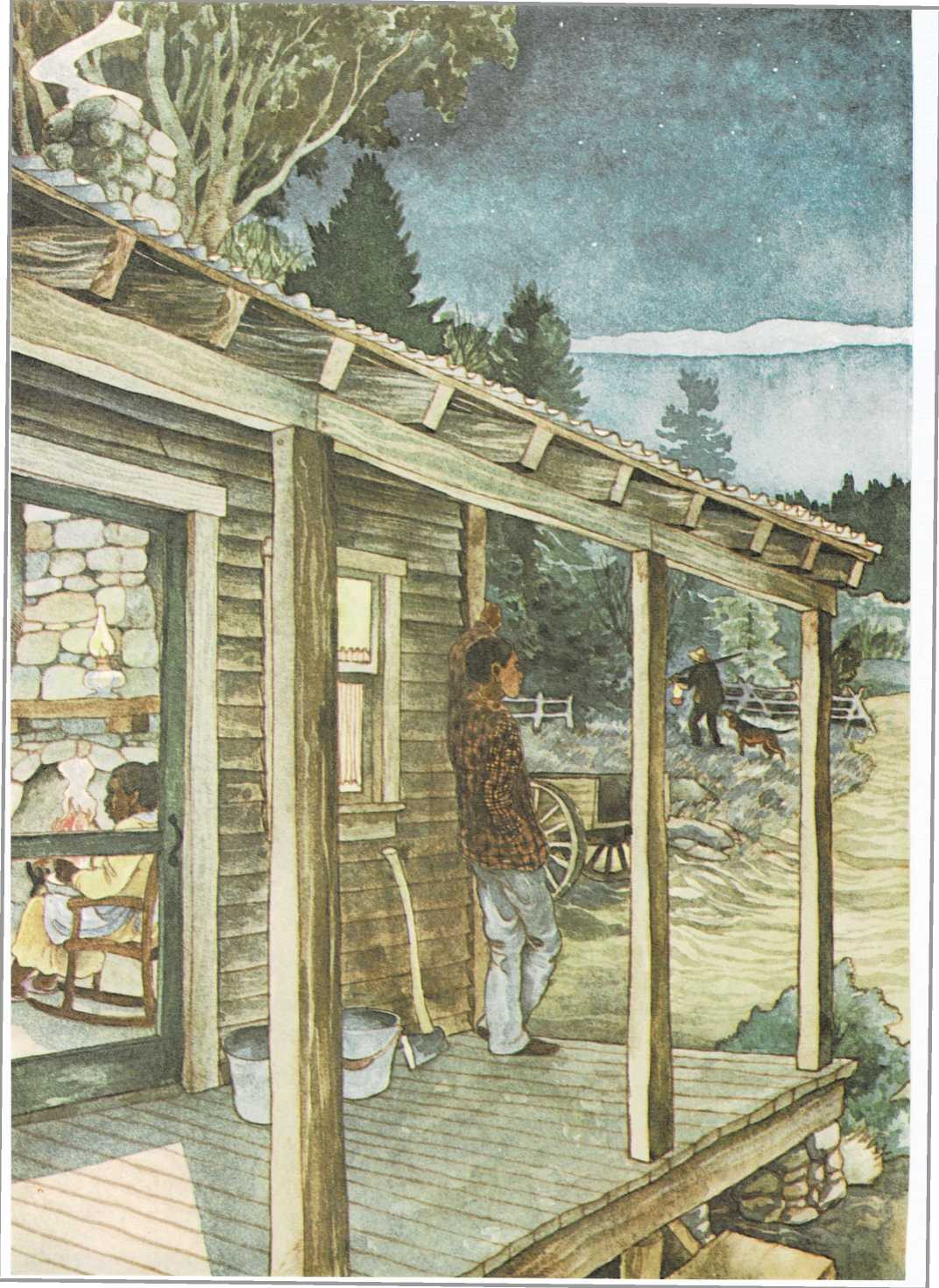

In the early darkness the halting, hesitant swing of the lantern marked

the slow path from fields to pine woods toward the lowlands. The boy

stood on the porch, watching until the light was lost behind pine

branches. Then he went and sat by the stove. His mother rocked as the

mound of kernels grew in the fold of her apron. “He been mighty peart,”

she said. “I hope he don’t fall in the dark. Maybe he’ll be happy now he

can go hunting again.” And she took up her singing where she had left

off.

Ain’t nobody else gonna walk it for you, You gotta walk it by

yourself.

Sounder, his master, the boy, and the boy’s mother all have the kind of

courage it takes to live through long, hard years. And that courage

helps to bring about some very important changes in the boy’s life. To

find out what they are, read Sounder. You’ll meet a very different

kind of dog in Good-Bye, My Lady by James Street. The “lady” washes

herself like a cat, laughs like a child, and becomes a most unusual

friend for Skeeter, the boy who finds her.

This be the verse you grave for me: *Here he lies where he longed to

be; Home is the sailor, home from sea, And the hunter home from the

hill.Requiem

by Robert Louis Stevenson

Under the wide and starry sky Dig the grave and let me lie. Glad did I

live and gladly die, And I laid me down with a will.