Stories

The Highwayman

by Alfred Noyes

Part One

The wind was a torrent of darkness among the gusty trees, The moon was a

ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas, The road was a ribbon of

moonlight over the purple moor, And the highwayman came riding—

Riding—riding—

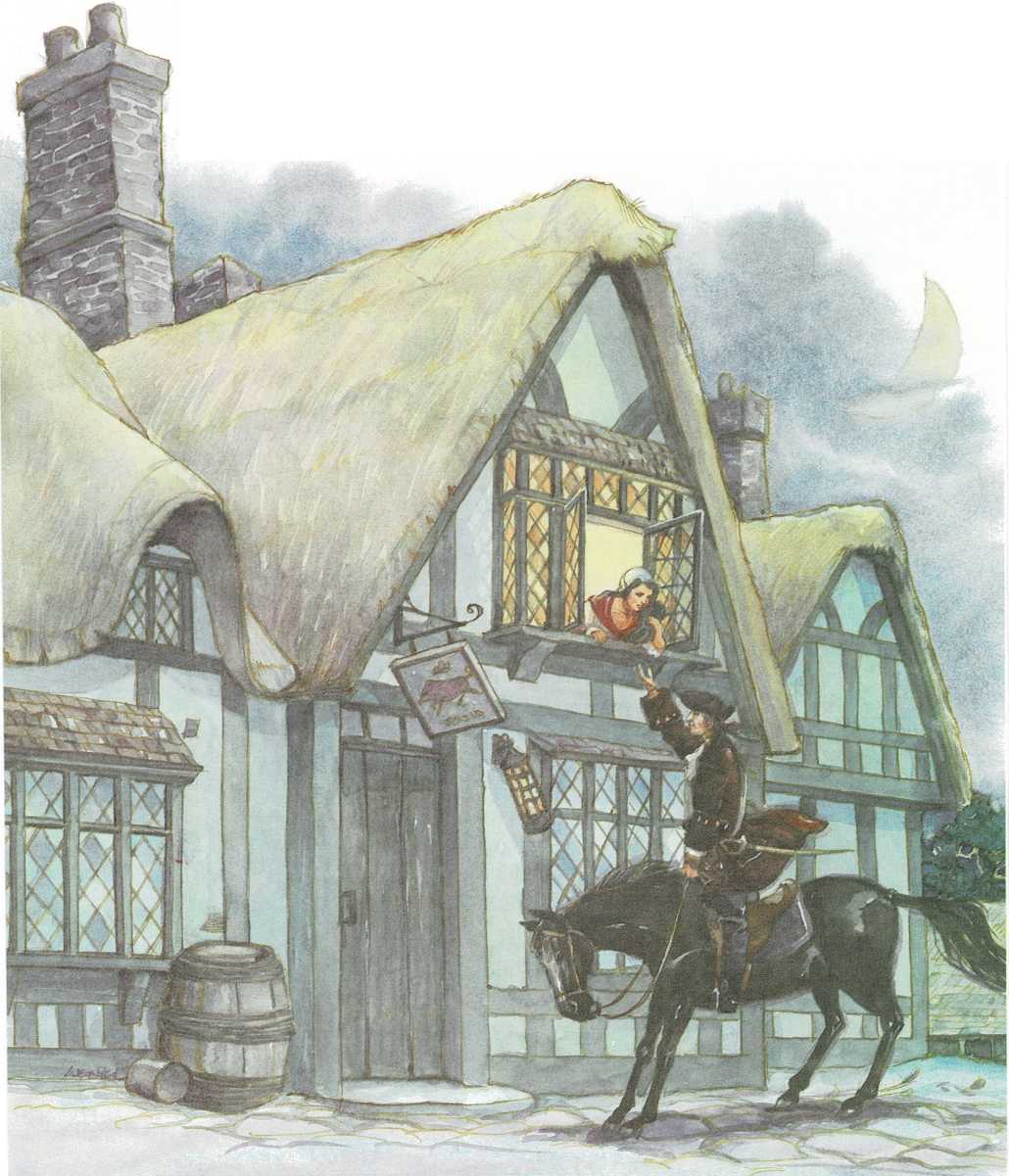

The highwayman came riding, up to the old inn-door.

He’d a French cocked-hat on his forehead, a bunch of lace at his chin, A

coat of the claret velvet, and breeches of brown doeskin: They fitted

with never a wrinkle; his boots were up to the thigh!

And he rode with a jewelled twinkle,

His pistol butts a-twinkle,

His rapier hilt a-twinkle, under the jewelled sky.

Over the cobbles he clattered and clashed in the dark inn-yard,

And he tapped with his whip on the shutters, but all was locked and

barred: He whistled a tune to the window, and who should be waiting

there But the landlord’s black-eyed daughter,

Bess, the landlord’s daughter,

Plaiting a dark red love-knot into her long black hair.

And dark in the dark old inn-yard a stable-wicket creaked Where Tim, the

ostler, listened; his face was white and peaked, His eyes were hollows

of madness, his hair like moldy hay;

But he loved the landlord’s daughter,

The landlord’s red-lipped daughter:

Dumb as a dog he listened, and he heard the robber say— “One kiss, my

bonny sweetheart, I’m after a prize tonight, But I shall be back with

the yellow gold before the morning light. Yet if they press me sharply,

and harry me through the day, Then look for me by moonlight,

Watch for me by moonlight:

I’ll come to thee by moonlight, though Hell should bar the way.”

He rose upright in the stirrups, he scarce could reach her hand;

But she loosened her hair i’ the casement! His face burnt like a brand

As the black cascade of perfume came tumbling over his breast;

And he kissed its waves in the moonlight,

(Oh, sweet black waves in the moonlight)

Then he tugged at his reins in the moonlight, and galloped away to the

West.

Part Two

He did not come in the dawning; he did not come at noon;

And out of the tawny sunset, before the rise o’ the moon,

When the road was a gypsy’s ribbon, looping the purple moor,

A red-coat troop came marching—

Marching—marching—

King George’s men came marching, up to the old inn-door.

They said no word to the landlord, they drank his ale instead;

But they gagged his daughter and bound her to the foot of her narrow

bed.

Two of them knelt at her casement, with muskets at the side!

There was death at every window;

And Hell at one dark window;

For Bess could see, through her casement, the road that he would ride.

They had tied her up to attention, with many a sniggering jest:

They had bound a musket beside her, with the barrel beneath her breast!

“Now keep good watch!” and they kissed her. She heard the dead man

say— Look for me by moonlight;

Watch for me by moonlight;

I\’ll come to thee by moonlight, though Hell should bar the way!

She twisted her hands behind her; but all the knots held good!

She writhed her hands till her fingers were wet with sweat or blood!

They stretched and strained in the darkness, and the hours crawled by

like years;

Till, now, on the stroke of midnight,

Cold, on the stroke of midnight,

The tip of one finger touched it! The trigger at least was hers!

The tip of one finger touched it; she strove no more for the rest!

Up, she stood up to attention, with the barrel beneath her breast, She

would not risk their hearing: she would not strive again;

For the road lay bare in the moonlight,

Blank and bare in the moonlight;

And the blood of her veins in the moonlight throbbed to her Love’s

refrain.

Tlot-tlot, tlot-tlot! Had they heard it? The horse-hoofs ringing

clear—

Tlot-tlot, tlot-tlot, in the distance? Were they deaf that they did

not hear?

Down the ribbon of moonlight, over the brow of the hill,

The highwayman came riding,

Riding, riding!

The red-coats looked to their priming! She stood up straight and still!

Tlot-tlot, in the frosty silence! Tlot-tlot in the echoing night!

Nearer he came and nearer! Her face was like a light!

Her eyes grew wide for a moment; she drew one last deep breath,

Then her finger moved in the moonlight,

Her musket shattered the moonlight,

Shattered her breast in the moonlight and warned him—with her death.

He turned; he spurred to the West; he did not know who stood

Bowed with her head o’er the musket, drenched with her own red blood!

Not till the dawn he heard it, and his face grew gray to hear

How Bess, the landlord’s daughter,

The landlord’s black-eyed daughter,

Had watched for her Love in the moonlight; and died in the darkness

there.

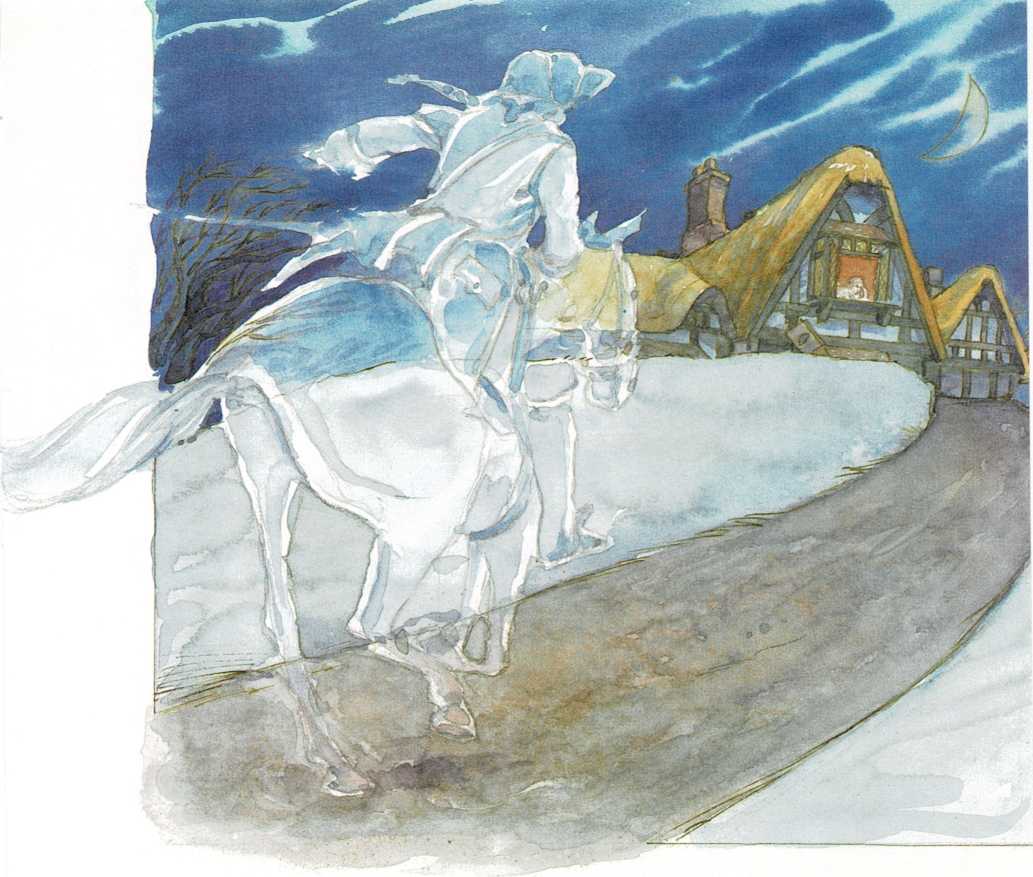

Back he spurred like a madman, shrieking a curse to the sky,

With the white road smoking behind him, and his rapier brandished high!

Blood-red were his spurs in the golden noon; wine-red was his velvet

coat;

When they shot him down on the highway,

Down like a dog on the highway,

And he lay in his blood on the highway, with the bunch of lace at his

throat.

And still of a winter’s night, they say, when the wind is in the trees,

When the moon is a ghostly galleon tossed upon cloudy seas, When the

road is a ribbon of moonlight over the purple moor, A highwayman comes

riding—

Riding—riding—

A highwayman comes riding, up to the old inn-door.

Over the cobbles he clatters and clangs in the dark inn-yard;

And he taps with his whip on the shutters, but all is locked and

barred: He whistles a tune to the window, and who should be waiting

there But the landlord’s black-eyed daughter,

Bess, the landlord’s daughter,

Plaiting a dark red love-knot into her long black hair.

—

from Hills End by Ivan Southall

The Storm

Elaine Godwin, a schoolteacher in a small Australian town, has a great

interest in the rocks, plants, and creatures of the surrounding

mountains. When Adrian, one of her students, tells of finding a cave

with paintings that must have been done by Aborigines a long time ago,

she is very excited. But most of Adrian’s friends think he has just

told another of his whoppers to get out of trouble. Together, they set

off into the mountains to find the cave.

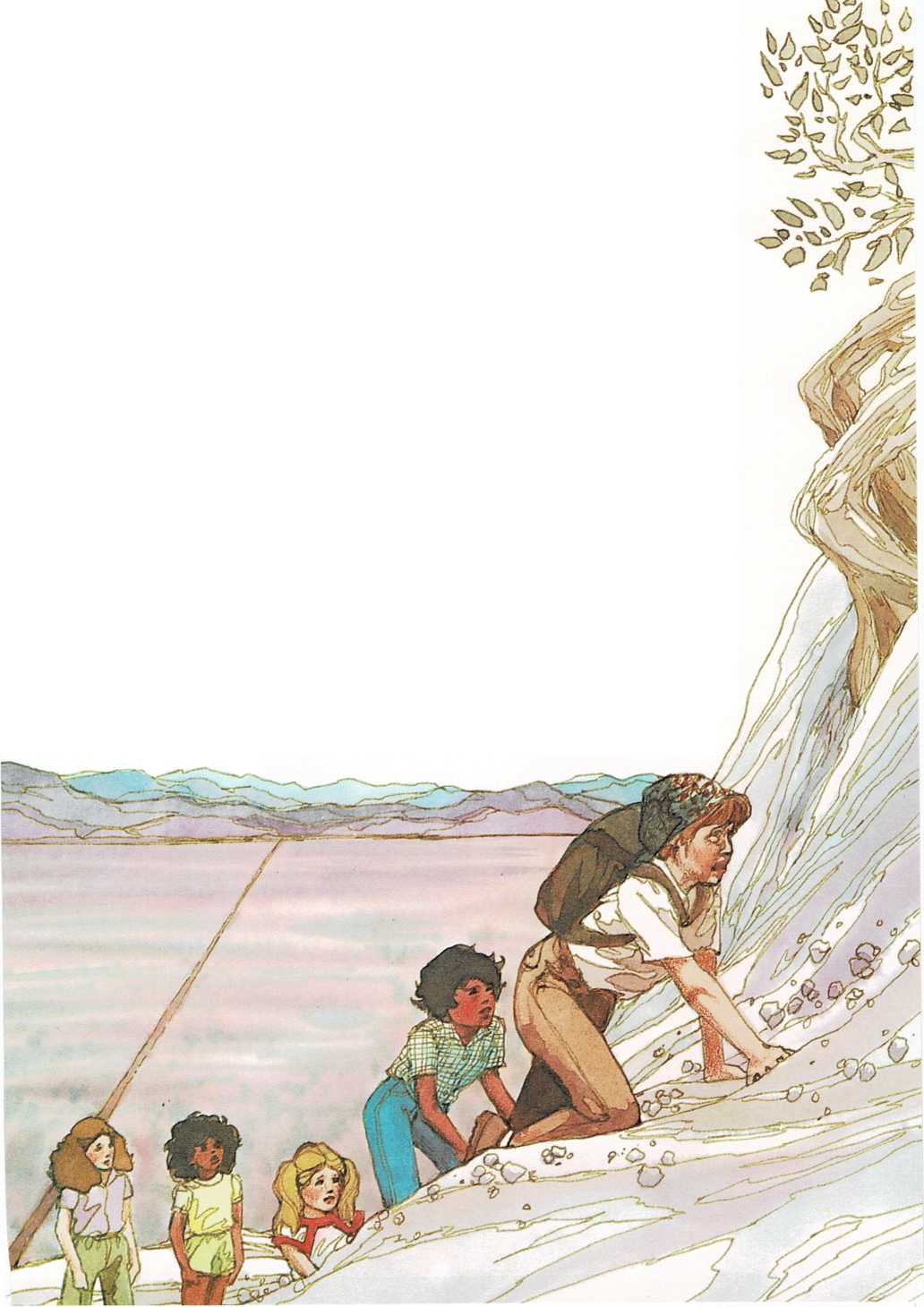

At the foot of the bluff Miss Godwin gathered her children round her.

She was guilty of deceiving them. They thought she only wanted to talk

but really she wanted to rest. She felt like a jelly inside, quivery and

without any strength. She knew now that this climb up the bluff was

every bit as bad as she had feared. This was why she hadn’t climbed it

when she had come before; it had been simply common sense, not

cowardice.

She drew her book from her haversack and it fell open at a photograph of

the rock paintings at Lightning Totem Centre in North Australia.

“. .. Now take a good look at these, Adrian, and tell me if you find any

similarities to what you saw.”

Adrian had been through this before. “No,” he said.

“You’re sure?”

“Certain, miss.”

“I’m going to ask you once more, Adrian, to go through the book from

cover to cover and make your selection. There must be similarities

somewhere.”

“I told you about the red hands, miss.”

“That doesn’t help much, Adrian. There are thousands of red hands

throughout the continent. It is their association with these other

things that is mystifying.”

Paul sighed inwardly. Of course the association was mystifying. It

wasn’t even true. But Miss Godwin had spoken about this, over and over

again. She was excited by it. She had kept harping on it, perhaps trying

to break Adrian’s story down, but Adrian’s story had never broken. He

hadn’t changed a detail. He had described things which, Miss Godwin

said, had never been found before. They must have been made a very long

time ago, perhaps thousands of years ago, by artists out of touch with

all other men.

So she waited while Adrian thumbed over the book again, from photograph

to photograph, endeavoring to steady her nerves and marshal her

strength. If she failed to make the climb what would these children

think of a teacher who taught them to explore but was afraid to explore

herself? What would they think of a teacher who enthused about the art

of the Stone Age men but was too frightened to make a personal effort to

see it?

“Really, miss,” said Adrian, closing the book and passing it back to

her, “it might be that I’ve forgotten, but I’m sure they were

different.”

“Very well, Adrian.” Miss Godwin glanced at her watch. “We’ll find out

how good an explorer you are. I think you’d better lead the way with

Paul, don’t you, and the rest of us can follow very carefully?”

“Yes, miss. There’s no danger really. It looks much worse than it is.

There’s only one thing. Don’t look down unless you’ve got something to

hang on to.”

“Do you hear that, children? Adrian says there’s no danger and Adrian

knows. But if any of you would rather stay down here just say the word.”

Gussie would have liked to have stayed, very, very much, but she was

frightened that everyone would tease her. She didn’t like the look of

the water trickling from the rocks, or the moss and the slime. And her

legs were aching, with the awful ache that she got sometimes and that

her mother called “growing pains.” It didn’t seem right that it hurt to

grow, Gussie thought, but perhaps that was why the trees groaned

sometimes. Perhaps it hurt them, too.

Maisie, too, was rather anxious, but she was frightened to speak up,

frightened that everyone would make fun of her.

“If it is an important discovery,” she said, “will we all be famous?”

“I don’t know about that,” said Miss Godwin. “Adrian will be the famous

one. We’ll have to name the discovery after him.”

“Golly!” said Paul, shaken for the moment. “Can we do that?”

“Of course we can. It’s our right, and if the Government agrees the

caves will be known by his name for ever and ever.”

“No kiddin’?” queried Adrian.

Miss Godwin coughed discreetly. “That isn’t quite the word, Adrian, but

it is a fact. They’ll be named in your honor.” Perhaps she was rueful

then. She wasn’t selfish, but it would have been nice if they had

suggested the discovery be named after her. She couldn’t expect children

to think of that.

“Come along, then. Let’s start.”

The heat was very trying and Miss Elaine Godwin shuffled up the face of

the bluff, perspiring freely, shaking so much at the knees that she was

sure they were knocking together. Dear, dear, dear! Why couldn’t she act

her age and admit it was too much for her? She was groaning for breath

and her pulse was beating so hard in her temples that all she could hear

was its thud-thud-thud. And, bless her soul, she’d have to get down

again afterward. That would be worse by far. It was this continual

patter of little stones, and the times she slipped on wet rocks or

slime, the times she looked down because the depths drew her eyes with a

dreadful fascination, the times she groped for a foothold and sent a

shower of fragments on the children beneath her. The times she was giddy

and her head swam, the times she wanted to scream at the top of her

voice, yet had to say so calmly, “Come along, children.”

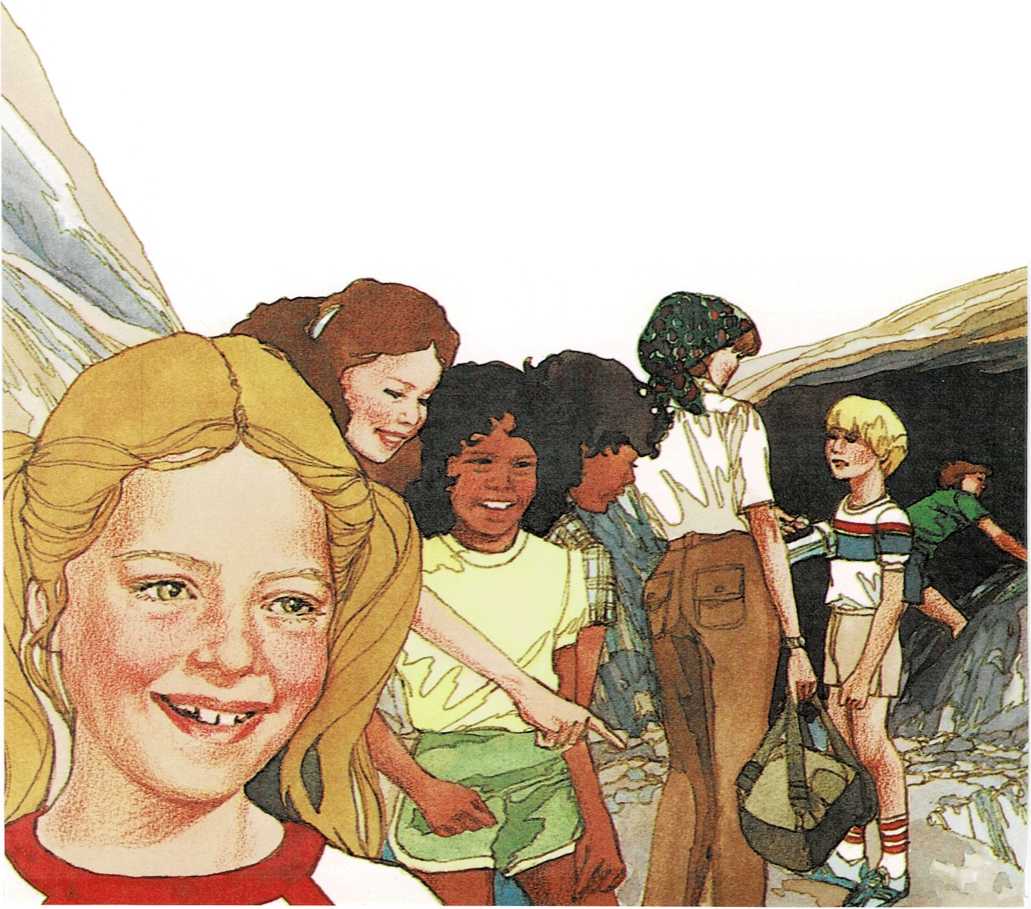

Suddenly she was there, on the wide ledge that formed the opening to a

cave, and Paul was smiling at her and Adrian seemed unusually subdued.

“Well, well, well,” she said breathlessly. “Here we are.”

Harvey, Gussie, Maisie, and finally Frances came up on the ledge behind

her. The girls were flushed and excited, full of their achievement

because not too many girls had got as far as this before. They had been

surprised to discover that the way up was far less dangerous than they

had been told. Of course, they had had to be careful, but no more

careful than in climbing a tree.

Miss Godwin was still fluttery and was finding it difficult to conceal

her distress. All she wanted to do was sit down, and she never knew how

she resisted the yearning. She was a brave soul and a far better leader

than she gave herself credit for. They never dreamed that she was

frightened, never imagined the state of her mind.

“Now, Adrian,” she said, “we’re in your hands.” “Have you brought a

torch, Miss Godwin?” “Of course. Of course. Always prepared.”

Miss Godwin’s torch was an electric lantern, six volts, and its power

would last for days.

“Is it very far in, Adrian?”

“No miss. So long as we find the right cave it’s only a few yards.”

“Goodness!” Miss Godwin was rather stern. “You have no doubt that you

can find it?”

“Oh, no. It might take a little time, but I’ll find it.”

“Very well. As I said, we’re in your hands. Take the torch. We don’t

know how soon we’ll need it. The sunlight won’t last for ever.”

It was Gussie who was left behind. She was so enthralled by the great

rock bed lying beneath her that these silly caves pitting the face of

the bluff seemed unimportant. She had climbed high, right up here, and

the view was the reward, the depth of space, the impression that she was

sitting in an airplane looking over the side. She simply didn’t notice

the sky until suddenly there were no shadows.

She glanced up and the sun had vanished behind the strangest looking

cloud she had ever seen. It seemed to have reached out of the north like

a big black arm and closed its hand round the sun.

“Ooh,” she said. “Look at that.”

She turned, and there was no one to look. They’d all gone.

“Oh, brother!” she said. “Wait for me. Wait for me!” “Goodness!”

exclaimed Miss Elaine Godwin. “What was that?”

She knew what it was, really, but she was so accustomed to putting

questions to children that she felt obliged to ask.

“That was thunder,” said Frances.

“Thunder, indeed. I hope we’re all not going to get wet on the way

home.”

She wasn’t thinking that at all. Her only thought was her fear of

descending the bluff. If rain came with the thunder the footholds would

be like glass, and somehow she was sure it was raining; although these

caves were warm there was in the air the touch and smell of water or

ice.

“Children,” she said, “I think we’d better go back to the entrance to

see what’s happening.”

“I’ll go, miss,” said Paul. “I know my way. I’ll only be half a minute.”

“Thank you all the same, Paul, but we must keep

together. We have only the one torch, and I don’t wish to be left in the

dark, nor do I wish you to be stumbling alone in the dark. Lead the way,

Adrian.”

“Fancy a storm on a day like this!” said Gussie. “Ooh!”

“Yes, Augusta?” said Miss Godwin. “What did you mean by that tone of

surprise?”

“I must have seen it coming. I saw a cloud. The funniest cloud you ever

saw.”

Miss Godwin shivered. “What was funny about it, Augusta?”

“It was like a big black arm, reaching across the sky, taking hold of

the sun.”

“You should have told me, child.” Her voice was so sharp that they were

surprised. “Hurry on, Adrian. If there’s to be a storm we must get out

of here.”

They followed the beam of the torch, this way and that way, but Miss

Godwin was bustling so busily on Adrian’s heels that she confused him

and he took the wrong turning. He wasn’t certain in his mind that he was

wrong, but the doubt was there, and Paul said, “Not this way, Adrian.”

“We’ll leave that to Adrian, shall we?” snapped Miss Godwin.

“But he might be right, miss,” stammered Adrian.

“I—I think he is right.”

“Nonsense. I distinctly remember this chamber.

Hurry on.”

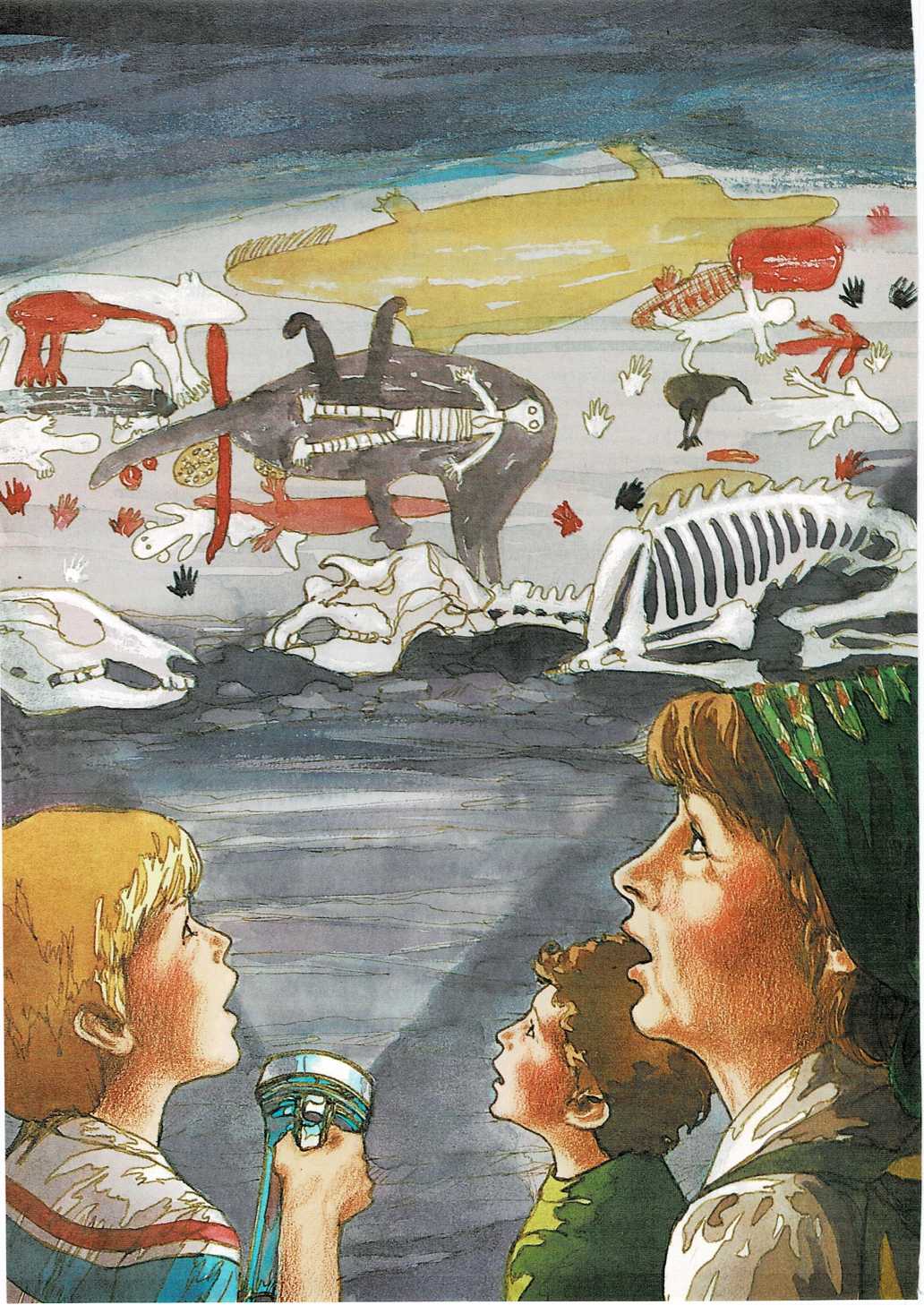

But Adrian knew he didn’t remember it, not from any of his journeys in

here, and when the pale whiteness of old bones moved into the beam of

the torch he was certain he’d never set foot in this cave before.

He heard the sharp intake of Miss Godwin’s breath close to his ear,

heard the squeal from Harvey and the gasp from Paul.

“Wait!”

Miss Godwin took the torch from Adrian and directed it across the floor

of the cave to a ledge. There were many bones, huge bones, and kangaroo

skulls twice as large as any they had ever seen, and on the walls beyond

were red hands and black hands and white hands and drawings of animals

and devil men.

Miss Godwin sighed, a deep, shuddering sigh, and Gussie cried out, and

Paul was so ashamed he wished the ground would open up and swallow him.

Adrian was panting in wonderment, in amazement, in absolute elation.

They were here. The drawings were here. And they’d called him a liar.

That prim and proper Paul had called him a liar and he wasn’t a liar at

all.

“I’m sorry, Adrian,” Paul murmured. “Golly, I am sorry!”

Frances, strangely, was a little saddened. She had believed Adrian yet

she was sorry that Paul had been proved wrong—and Gussie was all

confused. She had been so sure that Adrian had been lying. So very, very

sure, because Paul had been so sure.

Suddenly all were talking at once, and Miss Godwin had to raise her

voice to a shout. “Be quiet!”

She waited a few moments. “That’s better. That’s very much better. Now,

no one is to touch a single thing. Before we make any examination I want

to photograph everything just as we find it…. Adrian, this is a most

wonderful, wonderful discovery. My only regret is that I didn’t come a

week ago. Imagine it, children—Hills End will be famous. We’ll have

anthropologists coming here. Great scholars from all over the world.

Children, children, this is the most wonderful thing that has ever

happened to us. Oh dear, I—I’m really so excited. I’m all of a

flutter. Adrian, my boy.” She thrust her arm round him and hugged him

tight. “Why didn’t you tell us about the bones, too? Didn’t you think

they were important? They’re the bones of the giant kangaroo—and the

diprotodon, I think. Adrian, Adrian, these animals have been extinct for

tens of thousands—perhaps hundreds of thousands—of years….

Goodness me, I’m all of a flutter! I—I cannot believe my eyes. I’m

going to wake up in a minute. Oh dear, dear, dear!”

“You won’t wake up, Miss Godwin,” said Paul. “It’s real. Really and

truly real.”

She sighed again, a shivering and breathless sigh. “Take the torch,

Paul. Shine it on my haversack. I—I must get my things.”

She was trembling so much she could hardly undo the straps and she took

out her camera and her tripod and her flashlight fittings, and suddenly

heard the thunderclaps again and felt the cold air that was rapidly

expelling the warmth from the caves.

She looked up with a troubled frown and slowly stood erect, leaving her

precious equipment at her feet. “First of all,” she said, “I think we’d

better take a look at the weather. We mustn’t lose our sense of

proportion. These drawings will be here tomorrow—next week—they’ll

remain. We must take a look at the weather.”

“Now, miss?”

“Certainly, Adrian. But we must make sure that we don’t lose our cave.

It took a long while to find it, even though you were sure you knew

where it was. Now, what shall we do?”

“I’ll go, miss” said Paul. “I said before it would be all right.”

“No. We stay together. While you’re with me you’re my responsibility.

There had been no warning of a storm. This was some trick of the

weather. Some local disturbance…. “Now what shall we do? Of course,

what we want is a ball of string. That’s it. A ball of string. Always be

prepared, children. That’s the division between the foolish and the

wise.”

She took the ball of string from her haversack, tied the loose end

round a heavy stone, and directed Paul to proceed in front with the

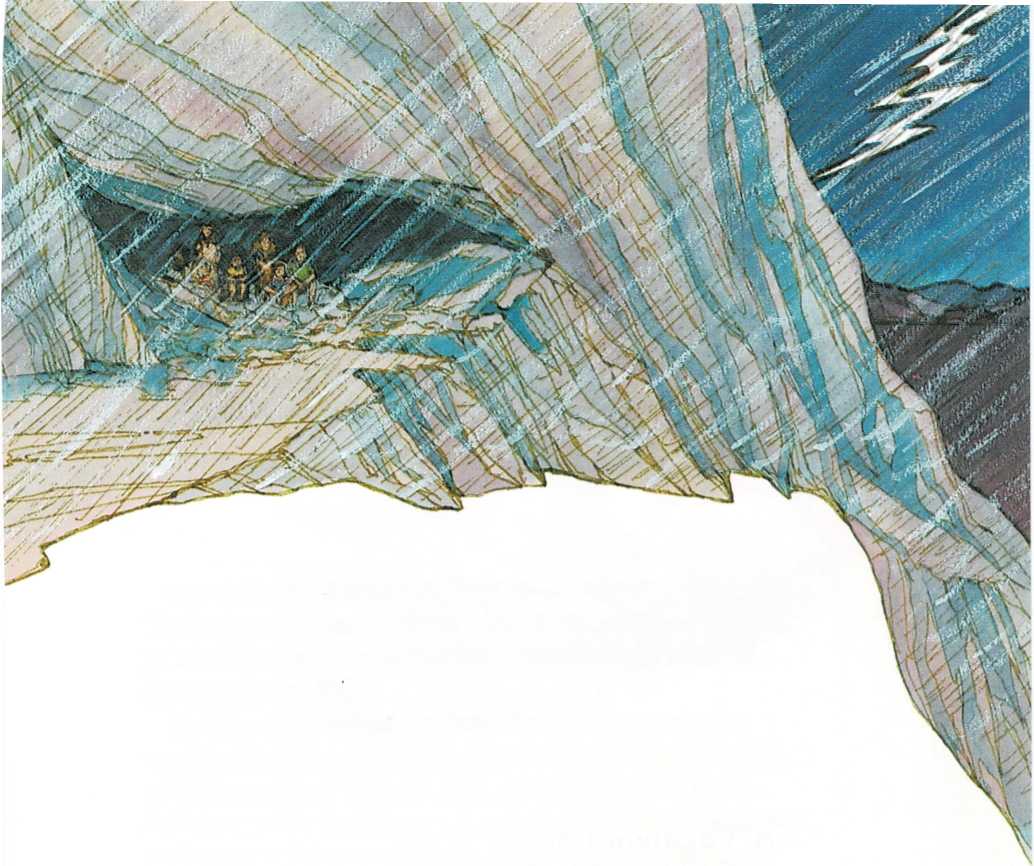

torch while she paid out the string behind her.So they came again toward the opening, toward a world of frightening

sound and vivid lightning flashes, of bitter cold, of violent wind, of

torrential rain and hailstones. The hailstones struck the ledge and

bounced and were as big as golf balls. They couldn’t approachthe opening. They had to stop well back, clear of showering ice and

wind-driven rain. The world beyond

was like a block of frosted glass—water, ice, and wind in a mass

through which they could not see.

The tremendous storm that sweeps over the mountains creates havoc. The

children, separated from their teacher, manage to get back to the town

of Hills End only to find it flooded and deserted. They are on their own

in a struggle to survive. Ivan Southall, the author of Hills End, is

one of Australia’s best writers of children’s books. Another of his

stories you might like is Ash Road, which is about a group of children

caught in the path of a devastating fire.