Stories

The Cow-Tail Switch

a West African folk tale

from The Cow-Tail Switch and Other West African Stories by Harold

Courlander and George HerzogNear the edge of the Liberian rain forest, on a hill

overlooking the Cavally River, was the village of

Kundi. Its rice and cassava fields spread in all

directions. Cattle grazed in the grassland near the river. Smoke from

the fires in the round clay houses seeped through the palm-leaf roofs,

and from a distance these faint columns of smoke seemed to hover over

the village. Men and boys fished in the river with nets, and women

pounded grain in wooden mortars before the houses.

In this village, with his wife and many children, lived a hunter by the

name of Ogaloussa.

One morning Ogaloussa took his weapons down from the wall of his house

and went into the forest to hunt. His wife and his children went to tend

their fields, and drove their cattle out to graze. The day passed, and

they ate their evening meal of manioc and fish. Darkness came, but

Ogaloussa didn’t return.

Another day went by, and still Ogaloussa didn’t come back. They talked

about it and wondered what could have detained him. A week passed, then

a month. Sometimes Ogaloussa’s sons mentioned that he hadn’t come home.

The family cared for the crops, and the sons hunted for game, but after

a while they no longer talked about Ogaloussa’s disappearance.

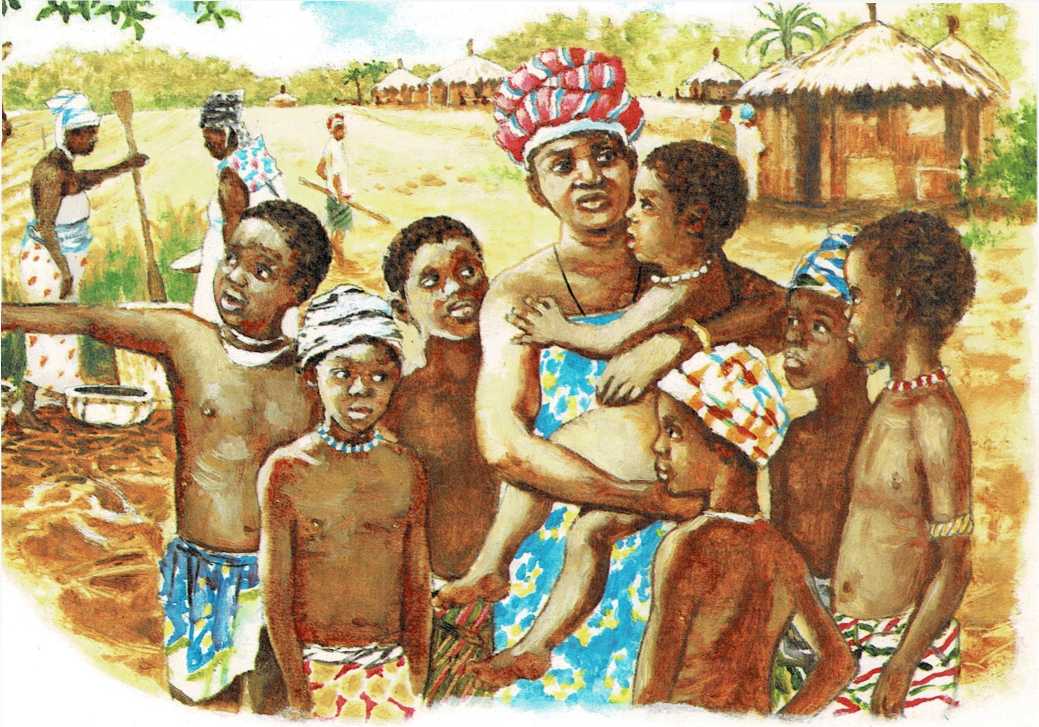

Then, one day, another son was born to Ogaloussa’s wife. His name was

Puli. Puli grew older. He began to sit up and crawl. The time came when

Puli began to talk, and the first thing he said was, “Where is my

father?”

The other sons looked across the rice fields.

“Yes,” one of them said. “Where is Father?”

“He should have returned long ago,” another one said.

“Something must have happened. We ought to look for him,” a third son

said.

“He went into the forest, but where will we find him?” another one

asked.

“I saw him go,” one of them said. “He went that way, across the river.

Let us follow the trail and search for him.”

So the sons took their weapons and started out to

look for Ogaloussa. When they were deep among the great trees and vines

of the forest they lost the trail. They searched in the forest until one

of them found the trail again. They followed it until they lost the way

once more, and then another son found the trail. It was dark in the

forest, and many times they became lost. Each time another son found the

way. At last they came to a clearing among the trees, and there on the

ground scattered about lay Ogaloussa’s bones and his rusted weapons.

They knew then that Ogaloussa had been killed in the hunt.

One of the sons stepped forward and said, “I know how to put a dead

person’s bones together.” He gathered all of Ogaloussa’s bones and put

them together, each in its right place.

Another son said, “I have knowledge too. I know how to cover the

skeleton with sinews and flesh.” He went to work, and he covered

Ogaloussa’s bones with sinews and flesh.

A third son said, “I have the power to put blood into a body.” He went

forward and put blood into Ogaloussa’s veins, and then he stepped aside.

Another of the sons said, “I can put breath into a body.” He did his

work, and when he was through they saw Ogaloussa’s chest rise and fall.

“I can give the power of movement to a body,” another of them said. He

put the power of movement into his father’s body, and Ogaloussa sat up

and opened his eyes.

“I can give him the power of speech,” another son said. He gave the body

the power of speech, and then he stepped back.

Ogaloussa looked around him. He stood up.

“Where are my weapons?” he asked.

They picked up his rusted weapons from the grass where they lay and gave

them to him. They then returned the way they had come, through the

forest and the rice fields, until they had arrived once more in the

village.

Ogaloussa went into his house. His wife prepared a bath for him and he

bathed. She prepared food for him and he ate. Four days he remained in

the house, and on the fifth day he came out and shaved his head, because

this was what people did when they came back from the land of the dead.

Afterwards he killed a cow for a great feast. He took the cow’s tail and

braided it. He decorated it with beads and cowry shells and bits of

shiny metal. It was a beautiful thing. Ogaloussa carried it with him to

important affairs. When there was a dance or an important ceremony he

always had it with him. The people of the village thought it was the

most beautiful cow-tail switch they had ever seen.

Soon there was a celebration in the village because Ogaloussa had

returned from the dead. The people dressed in their best clothes, the

musicians brought out their instruments, and a big dance began. The

drummers beat their drums and the women sang. The people drank much palm

wine. Everyone was happy.

Ogaloussa carried his cow-tail switch, and everyone admired it. Some of

the men grew bold and came forward to Ogaloussa and asked for the

cow-tail switch, but Ogaloussa kept it in his hand. Now and then there

was a clamor and much confusion as many people asked for it at once. The

women and children begged for it too, but Ogaloussa refused them all.

Finally he stood up to talk. The dancing stopped and people came close

to hear what Ogaloussa had to say.

“A long time ago I went into the forest,” Ogaloussa said. “While I was

hunting I was killed by a leopard. Then my sons came for me. They

brought me back from the land of the dead to my village. I will give

this cow-tail switch to one of my sons. All of them have done something

to bring me back from the dead, but I

have only one cow-tail to give. I shall give it to the one who did the

most to bring me home.”

So an argument started.

“He will give it to me!” one of the sons said. “It was I who did the

most, for I found the trail in the forest when it was lost!”

“No, he will give it to me!” another son said. “It was I who put his

bones together!”

“It was I who covered his bones with sinews and flesh!” another said.

“He will give it to me!”

“It was I who gave him the power of movement!” another son said. “I

deserve it most!”

Another son said it was he who should have the switch, because he had

put blood in Ogaloussa’s veins. Another claimed it because he had put

breath in the body. Each of the sons argued his right to possess the

wonderful cow-tail switch.

Before long not only the sons but the other people of the village were

talking. Some of them argued that the son who had put blood in

Ogaloussa’s veins should get the switch, others that the one who had

given

Ogaloussa’s breath should get it. Some of them believed that all of the

sons had done equal things, and that they should share it. They argued

back and forth this way until Ogaloussa asked them to be quiet.

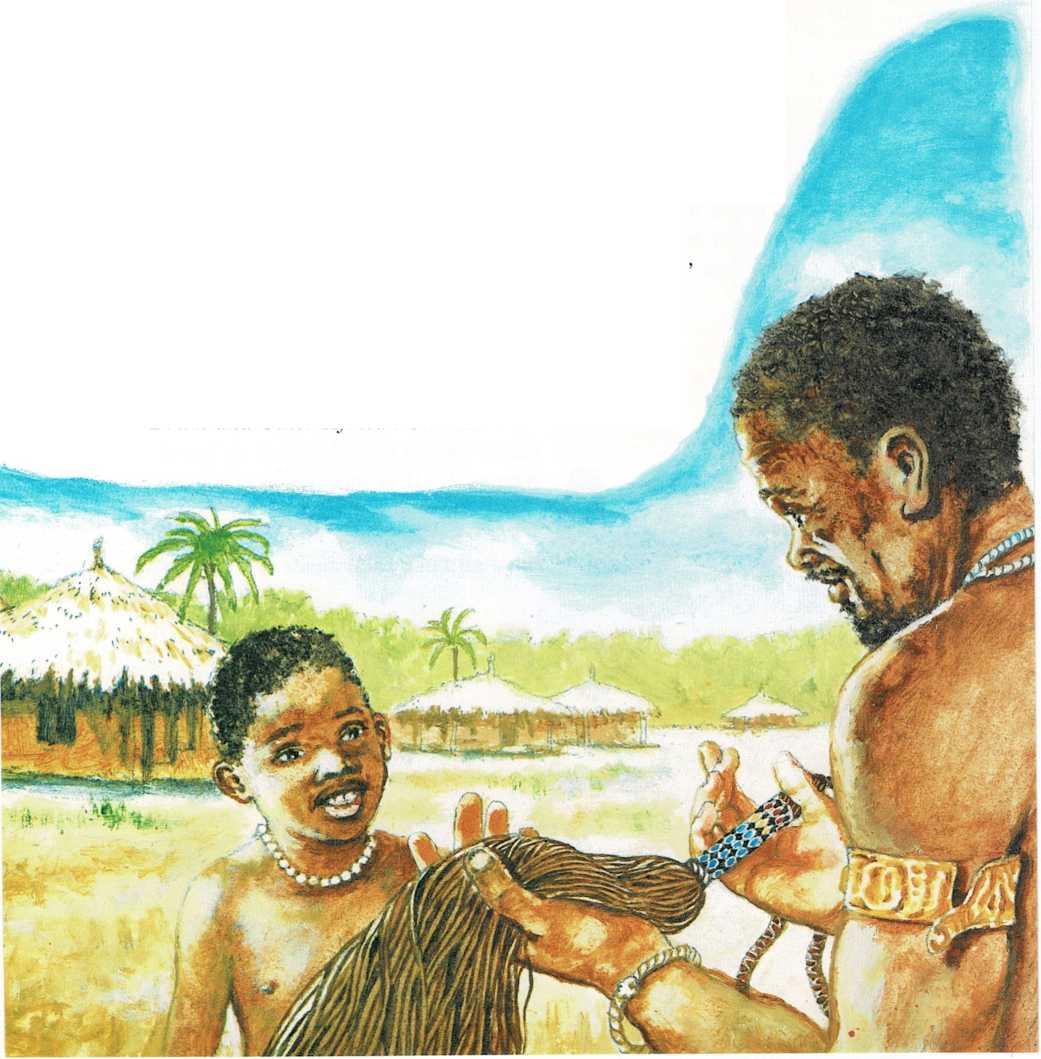

“To this son I will give the cow-tail switch, for I owe most to him,”

Ogaloussa said.

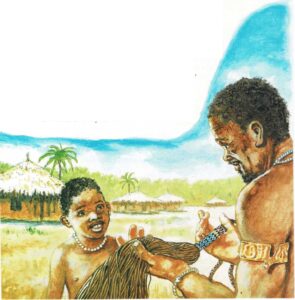

He came forward and bent low and handed it to Puli, the little boy who

had been born while Ogaloussa was in the forest.

The people of the village remembered then that the child’s first words

had been, “Where is my father?” They knew that Ogaloussa was right.

For it was a saying among them that a man is not really dead until he is

forgotten.

J A … .. –

In The Cow-Tail Switch and Other West African Stories, you will find

seventeen more wonderful tales. Other books of African folk tales, all

written or coauthored by Harold Courlander, include Olode the Hunter

and Other Tales from Nigeria, The Hat-Shaking Dance and Other Ashanti

Tales from Ghana, and The King’s Drum and Other African Stories.