Stories

The Challenge

from Sea Glass by Laurence Yep

Craig is a Chinese-American boy who has lived in San

Francisco’s Chinatown all his life. Then, when he is in eighth grade,

his family moves back to the small coastal town where his father grew

up. Craig is not very popular. He is overweight, awkward, and no good at

sports. He is also too Chinese for his Americanized cousins and too

American for the old Chinese man who becomes his friend.

I wasn’t very comfortable with any of the old-timers. But the one

old-timer who really got to me was this spooky one I never got to see

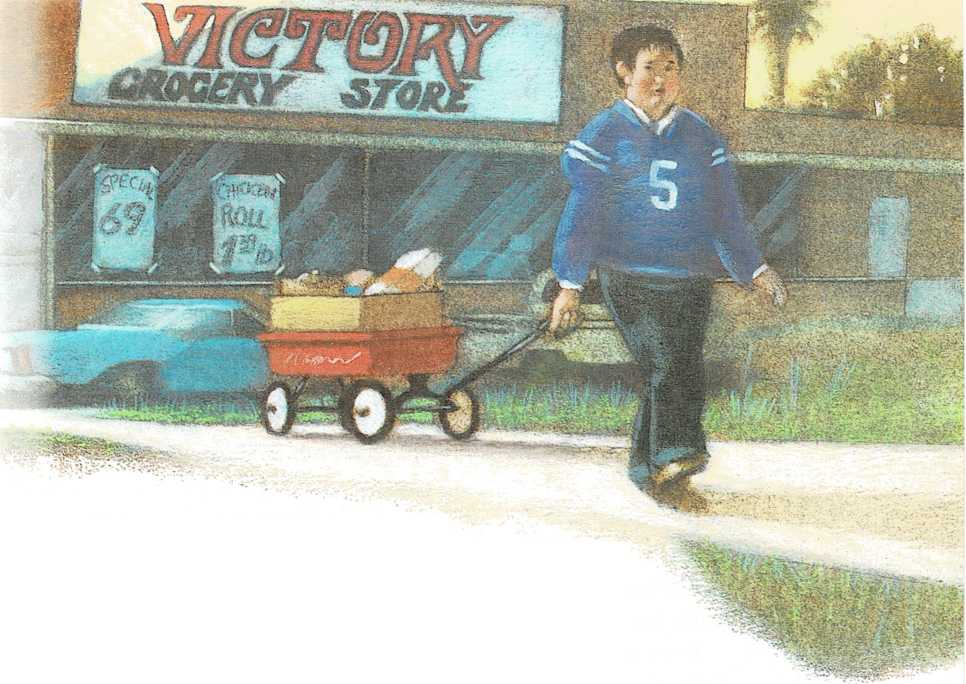

for week after week. His name was Uncle Quail. Of all the grocery

deliveries I had to make, going to his cottage was the longest and the

hardest trip, so I always delivered his groceries last in the afternoon.

I thought of Uncle Quail as some kind of ogre after Uncle Lester’s

stories. Uncle Lester, who actually owned the Victory Grocery Store, was

only a friend of Dad’s and no blood relation to us; but he had said that

his uncle Quail was a blood relative—something like a great-uncle or

even a great-great-great-uncle. Uncle Quail had always been here as

far as Uncle Lester knew, and Uncle Quail had always been one of the

store’s liabilities—like the mortgage, the leaking roof, and the mice.

You see, Uncle Quail received his groceries for free.

Every week I brought him the same things from the list. There were cans

of peas and soup, and a small bag of rice, and other things like

sardines and seven cigars. Uncle always wanted yams—fresh when they

were in season, otherwise he took canned ones. There also had to be a

freshly killed chicken. Uncle Lester had instructed Dad to pay a nearby

farmer special to bring in a freshly killed chicken every week. Dad had

to pluck and clean it, though.

Anyway, during all those months I had been delivering Uncle’s groceries,

I was kind of grateful that he hadn’t come out to talk to me.

Then came that one Saturday in April.

It started out like any other trip. First, I had to go through the part

of town that was one of the oldest; the street was shaded by big poplar

trees whose roots tilted up the sidewalk sections so that the slabs

looked like the waves of a stormy sea that had been frozen suddenly. It

wasn’t any fun pulling the wagon up and down the slabs of sidewalk. But

the fun really began when the sidewalk came to an end, and I had to pull

the wagon along the dirt road.

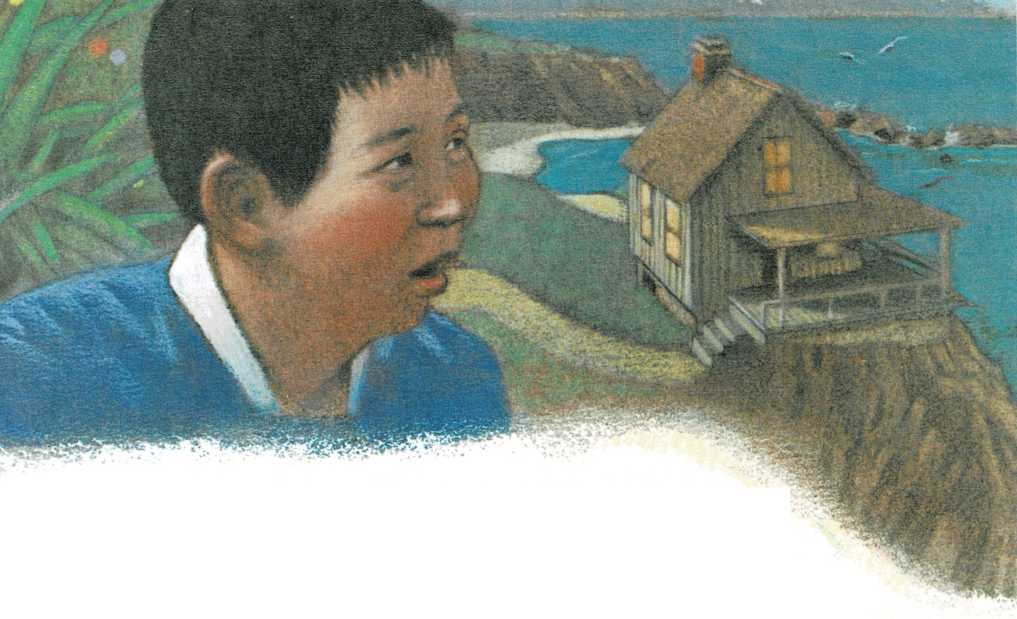

When I reached the cliffs, I stopped and took a breath before I started

up the sandy path that zigzagged to the top. A dirt track led across the

top of the cliffs, and I pulled the wagon along past the brown weeds and

the scraggly windblown trees that grew there. I stopped by the old rusty

wire-mesh fence. The gate was unlocked, as it always was on Saturdays.

The open padlock hung to the side on one of the wires.

Carefully I lowered the wagon down the stone path to Uncle’s house.

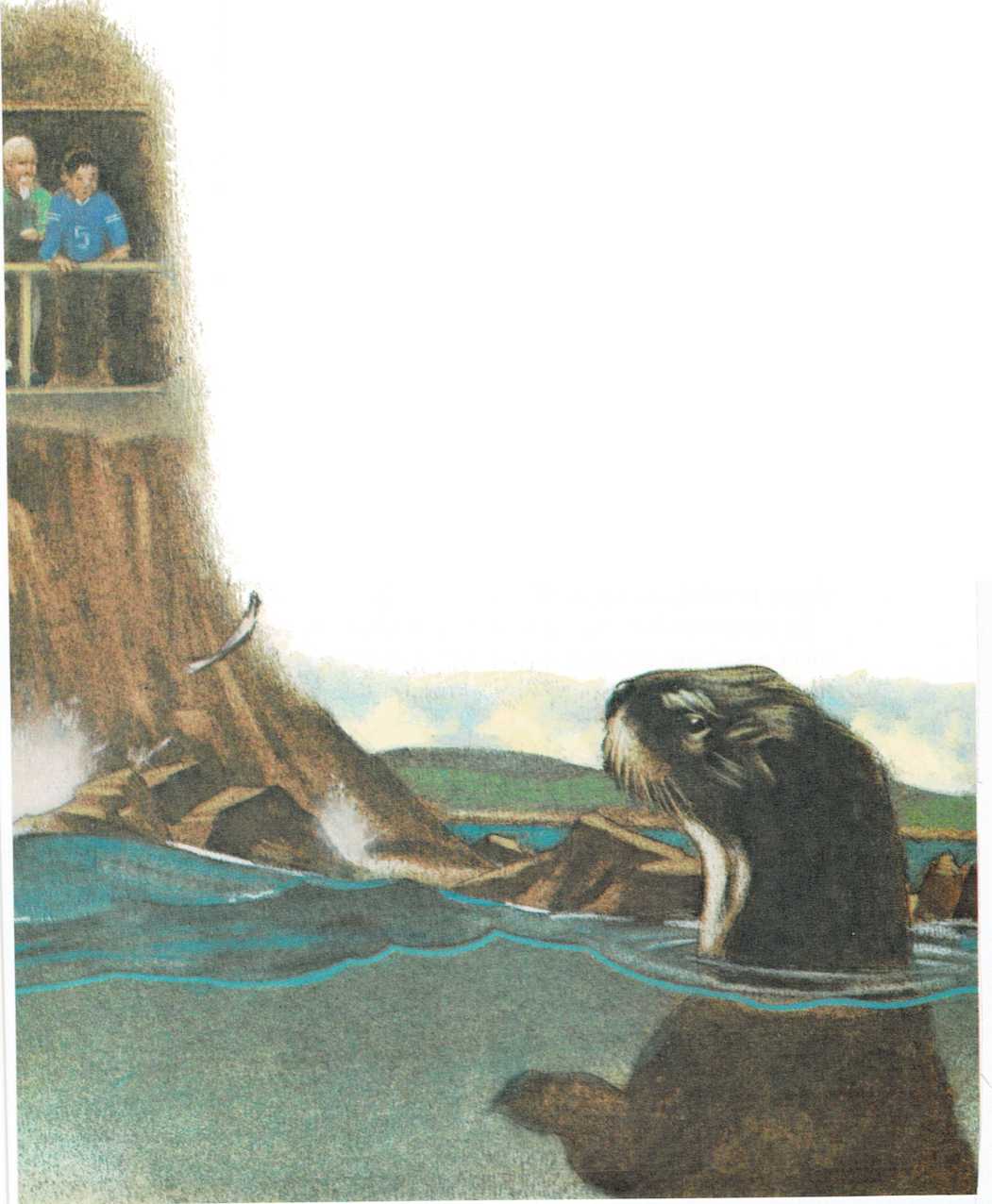

Uncle lived on a small cove about fifty feet across that was formed by

the cliffs and a headland. The rock had crumbled at the mouth of the

cove a long time ago, maybe in some storm when the heavy waves had come

crashing in, and now lay piled across it to form a reef that protected

the cove from the rest of the sea—except for that one narrow opening

in the reef. Right now it must have been high tide, because only the top

of the reef showed.

There was only a little strip of beach at high tide, and I couldn’t see

the wooden pilings where Uncle used to have a small wharf. A stone path

wound up the cliff wall behind the beach for about fifty feet before the

path widened out to a ledge about thirty by forty feet. It was there

that Uncle had built his little wooden cottage. The paint had worn off

long ago, leaving the wooden planks exposed to the wind and the salt

spray so that the wood was a grayish color and smooth as the surface of

a skull.

There were shades over the windows, shades so old that they looked an

orange-goldish color. Sometimes I thought I saw one of the shades

stir—like an eyelid twitching. And I would have this spooky feeling

like someone was watching me.

I would always shove the new carton of groceries and bunch of the past

week’s Chinese newspapers onto the porch. Then I’d take the old box,

which was filled with garbage that Uncle had wrapped neatly in last

week’s newspapers. I’d put the box into the wagon and I’d tear back up

the path with the almost-empty wagon rattling and bumping along behind

me.

But today it was different.

I had just put the carton of groceries on the porch of Uncle’s house

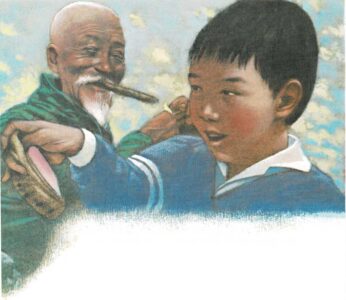

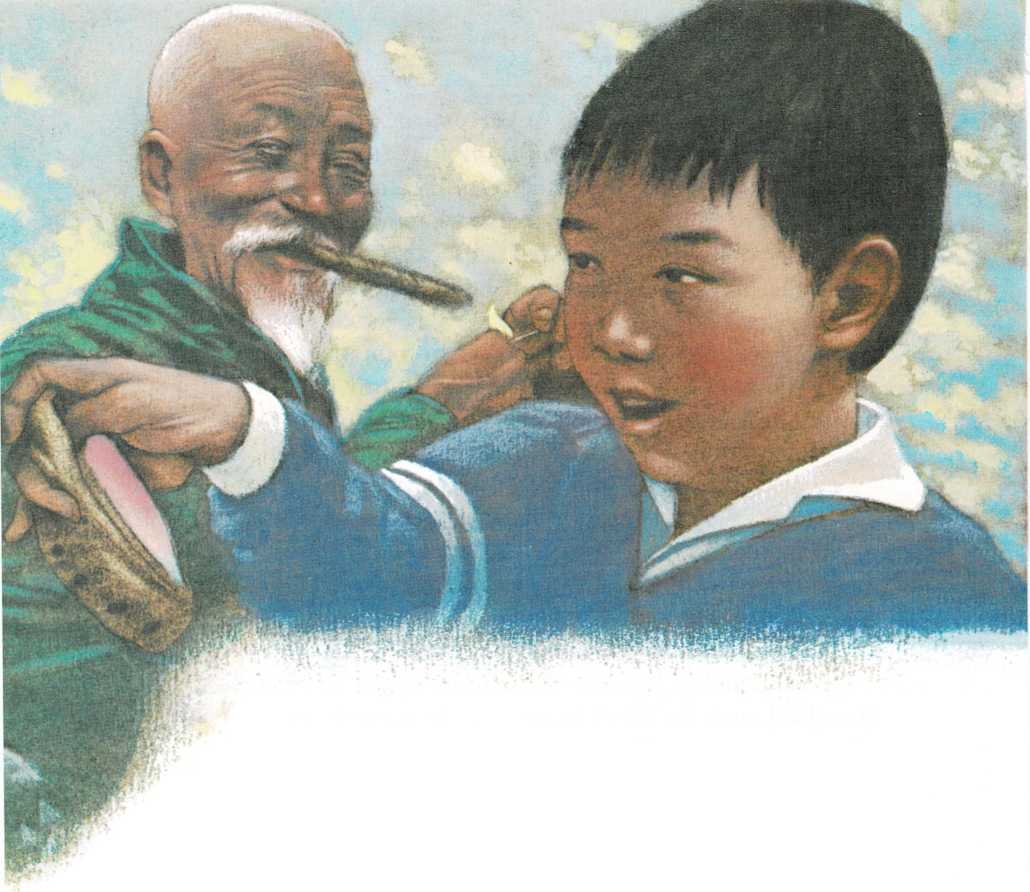

when the door suddenly opened and an elderly Chinese in his seventies

stood there.

On his feet he had a pair of Chinese slippers with dragons embroidered

on the front. His legs were encased in a pair of old gray work pants

that sagged like elephant legs. Over a torn T-shirt, Uncle wore an

old green jacket that came only to his waist. The lining on the inside

obviously had once been of bright bands of yellow, red, and green in

some silklike material, but the coat was torn now at the bottom, and

though Uncle Quail had tried to mend it, the material had been too old

and worn, so that his jacket had torn again, letting the padding begin

to trail out once more.

He held out his hand to me and said something in Chinese, but too

quickly for me to understand. Then he spoke more slowly, barely able to

contain his impatience.

\”‘Quick, boy. I want the sardines.” The last word was in American.

When I just stared at him, he gave a little contemptuous sigh and dug

around in the carton himself, scattering cans left and right onto the

porch. I looked over the railing down at the cove fifty feet below his

house. A small shadow circled underneath the surface of the water.

“What\’s that?” I asked in Chinese. I turned back to Uncle. He had

pried the key off the bottom of the can and fitted it onto the metal tab

on the top. Then he began to wind the entire lid down.

In the meantime, the creature had surfaced so I could see it was an

otter. He stared at us for a moment; then he began to clown in the

water, rolling and spiraling and tumbling.

“Quit showing off” Uncle pretended to scold the otter. With a flick of

his wrist, Uncle threw a fish up high into the air. It glittered as it

fell through the sunny afternoon air: a silvery flake that splashed into

the water near the otter’s head. The otter dove, surfacing to float on

his back with the fish between his humanlike paws. He ate with big nods

of his head as he gulped it down.

Uncle wiped his fingers on the seat of his pants and glanced at me.

“You want to try it?” He held the can in front of me. I slipped a

sardine out and threw it. It

almost hit the otter on the stomach. He looked so surprised and

indignant that Uncle and I both had to laugh. It didn’t seem to bother

the otter, though, because he dove for the fish. We took turns feeding

him after that. The otter seemed to realize when the tin was empty,

because he began to circle the cove.

I watched him slide around in the water. It was hard to think of him as

flesh and bone. He curled around so fast and darted away that he seemed

more like a brown streak that someone was trying to paint on the water,

only the water kept on shrugging off the paint. It almost hurt inside me

to look at him. That otter was so sleek and fast and

graceful—everything I had ever wanted to be and wasn’t. I held on to

the porch railing so I could lean far out to catch one last glimpse as

he shot through the narrow opening in the reef at the mouth of the cove

and out into the open sea. And then I couldn’t see him anymore.

Uncle said something more in Chinese.

“Pardon me?” I asked.

Uncle spoke in American. “I said he’s very

beautiful.” He switched back to Chinese. “What’s the matter: Don’t you

speak the language of the T’ang people?”

“Only a little,” I confessed. I waited for him to begin ranting like

Ah Joe had done.

Uncle grunted like he wasn’t surprised in the least at my stupidity.

“You speak. You act. You even think like a white demon.” By demon,

he meant an American. With a very stern expression on his face, he

stared at me.

I was more intimidated by Uncle than I had been by Ah Joe. Though Uncle

Quail was in his seventies, he still moved quickly and yet

gracefully—as if his body could barely contain all of his energy. His

hair, which he cut short on top and almost shaved on the sides and back

of his head, only accented the bullet shape of his skull. His shoulders

were still broad and heavily muscled.

“Well, little demon, someone squeezes my bread too much.” He made

wringing motions with his hands as if he were twisting the water out of

a wet towel. “Is it you?”

“I guess I just grab it too hard when I’m in a hurry.” I rubbed

nervously at a patch of dirt I’d gotten somehow on my left elbow.

“I only make toast with it anyway,” Uncle said, “but I don’t want toast

that is all twisted. How you like it if I pay you with bent coins,

hunh?”

“I’ll be more careful the next time,” I promised.

“I wait and see.” Uncle clasped his hands behind his back. “What’s your

name, boy?”

“Craig. Craig Chin.”

“Ah.” Uncle scratched for a moment behind his ear. “Are you Calvin’s

son?”

“Yes, sir.”

“He and Lester, they used to bring my groceries. Just like you, hah?” He

waved his hand back and forth between me and him. “But that was a long,

long time ago.” Uncle paused as if he were searching for something else

to say. “Your father was strong. Even when he was small. Very strong.”

Uncle closed his hands into fists and pretended to make his muscles

bulge. “He always play the demon games even then.”

Even down here I couldn’t escape from Dad’s reputation. “Oh” was all I

said.

“And you? You like the demon games?” Uncle asked kindly.

“Sort of,” I said without much enthusiasm. Somehow, whenever I got to

talking to people about my dad, they always wound up asking me if I

liked sports. They assumed not only that I did, but that I would be as

good at them as Dad had been. I went on quickly. “But I’m not very good

at sports.” I glanced at the box with Uncle’s garbage neatly wrapped in

newspaper and began to think of excuses for leaving.

But instead of going on with his questions as other people would have

done, Uncle was silent. When I turned around to say good-bye to him, I

found him studying me. There was a fine network of wrinkles around his

eyes, but I hadn’t noticed them before because his face had been more or

less relaxed. Now, though, his forehead was wrinkled and his eyebrows

were drawn together, and there was a deep, intense look to his eyes. For

a moment, I felt more alive: as if I ought to be like the sunlight

leaping from the back of one ocean wave to another.

Then Uncle blinked his eyes and the look slipped away from his face. He

smiled at me reassuringly. I felt the corners of my mouth turn up into a

brief, uneasy grin. It was as if Uncle understood that I didn’t want to

be asked any more questions about how good I was at sports.

For a long time, neither of us knew what to say to the other. Finally

Uncle faced toward the cove. “You … you like my friend?”

I could only nod my head in agreement. We had something to share after

all. I think that fact pleased the both of us. “Does the otter come here

often?”

“That lazy thing? He only comes when he feels like it. One of these

days, no more fine meals from me.” Uncle did his best to sound as if he

disapproved of the otter because he begged for food. It was actually, as

I was to learn, just Uncle’s way never to compliment anything

wholeheartedly. Uncle added sternly, “It’s a waste of good food.”

Even so, I knew he ordered two cans of sardines every week, because I

was the one who filled his order for groceries. It was written on a

scrap of butcher paper in pencil that had gotten smudged over the

months. I suppose Uncle had dictated the list to his relative, Uncle

Lester.

“Will the otter be back today?” I asked Uncle.

Uncle scratched the side of his nose. “I not think so.” He added, as if

he didn’t know what to do with me, “But you can wait if you want.”

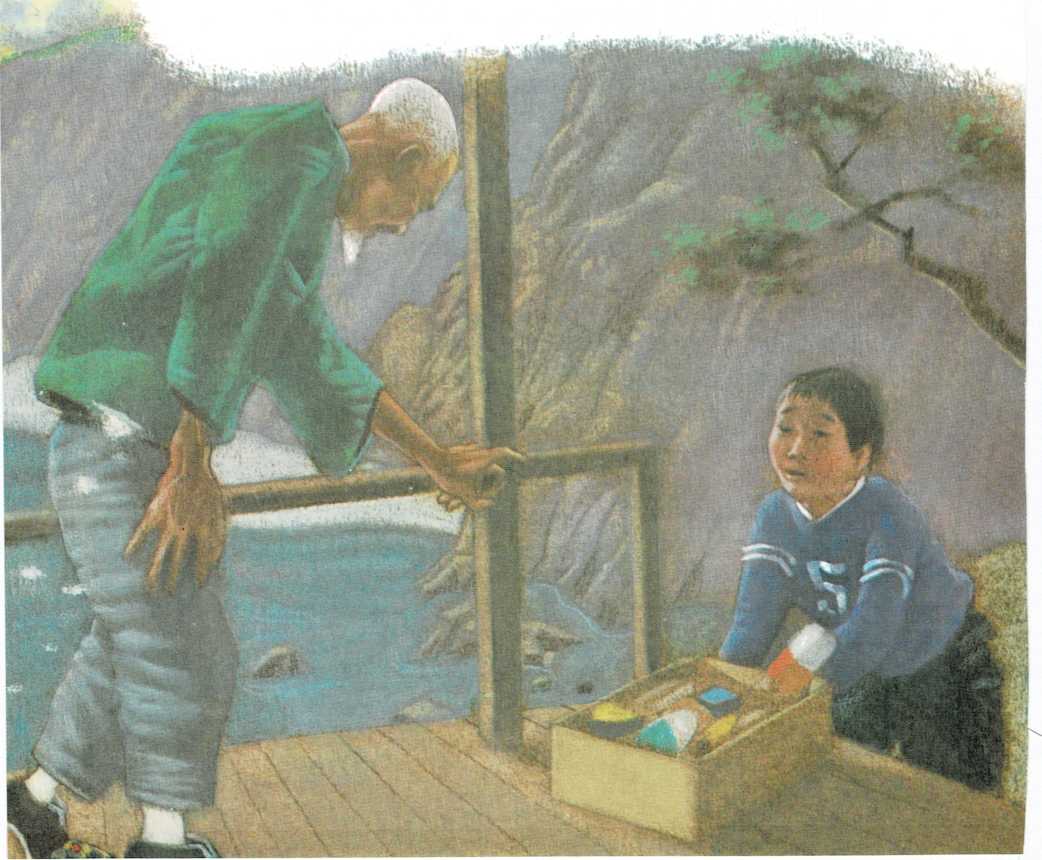

“I guess I could stay a little while.” I sat down on the porch and began

to pick up the cans that Uncle had scattered all around while he had

been hunting for one of the sardine cans. As neatly as I could, I put

the cans back into the carton.

Uncle picked up the seven cigars from the porch where he had tossed them

earlier. Then he sat down carefully on the porch beside me. He stretched

one leg out stiffly and rubbed it as if it ached. With his other hand,

he stowed six of the cigars into a jacket pocket. Finally he unwrapped

the seventh cigar and bit off one end, spitting out the little mouthful.

Then he reversed the cigar and stuck it into his mouth. Clenching it

between his teeth, he hunted around in his pants pocket and took out a

book of matches. His other hand groped around on the porch until it

found a black ugly shell by the left railing. The shell was about

seven inches long. But when he turned it over, I saw the inside was all

silvery, with a beautiful swirl of metallic colors rippling and flowing

around the insides as if this were half of a shell that had hatched a

rainbow.

While he lit his cigar, I studied the shell in fascination. “Where did

you get that?”

“This?” Uncle held up the shell as if he took it for granted. “It’s only

an abalone shell. No good. Got too many cracks.”

“I’ve eaten abalone. I thought they were fish.”

“No, boy.” Uncle laughed. He waved his cigar toward the cliff. “In the

old days there was a whole bunch of us catching abalone south by

Monterey. We cut the meat and put it on trays so the meat dries. Then we

send the meat to China. We sell the shells, too. Some months you could

shut your eyes and just smell the

air.” Uncle closed his eyes and pretended to sniff at the air. “And you

find our camp.”

With great care, Uncle slowly took the cigar from his mouth so that the

ash stayed there until he could tap his cigar against the side of the

abalone shell—it was as if he were playing a game with himself. “Hey,

you know what, boy?” He glanced at me sideways. “I find abalone on my

reef still.” He jabbed his cigar at the air in the direction of the

reef. “Someday I take you out there and we dive for abalone.” He added,

“But you think you could keep it a secret? I don’t want everyone down

here.” He turned and looked at me shrewdly.

“I can keep a secret,” I said doubtfully, “but do we really have to swim

out there?”

Uncle grunted. “Maybe I see how well you swim. The abalone, they don’t

come crawling into your hand, you know.” Uncle was doing his best to

sound disinterested, but I could hear the eagerness in his voice.

Even so, I hesitated. “I don’t know.” I didn’t want to disappoint Uncle,

and yet I didn’t know how to tell him that I found it embarrassing to go

swimming. Once, when we were still in San Francisco, I’d gone to Ocean

Beach with some friends, and I felt real stupid there. I’m fat. I wore

an extra-big T-shirt to cover up my stomach. And my swimming trunks were

large ones and they hung down almost to my knees. I felt like all the

average, thin people were looking at me and snickering.

Uncle sucked at his cigar and then blew out a large circle. “Don’t you

worry, boy,” he said gently. “Most of the time nobody comes up here, so

nobody can see us.” It was as if he could read my mind. Sometimes you

meet people who like having other people around so they can have an

excuse to hear their own voices talking. But as I came to know Uncle, I

found that he could understand people—almost as if he could read

people’s minds and didn’t much like what he read there so he usually

didn’t make the effort. Uncle knocked some more ash into the shell. “You

know, it’s a funny thing, but I don’t like people watching me. A few

times people come up to the cliffs, but then I can smell them so I go

inside.”

I looked down at the seawater surging up the sand. It was like a thing

alive, with gold scales winking and disappearing and reappearing again

on the surface. And outside the cove I could see the separate shades of

water in the sea. It certainly looked inviting.

But then I let myself imagine what Mom and Dad would say, especially

Dad, when I gave them an abalone shell as a decoration for our house.

Maybe if I had two, I could show one of the shells to the other kids. I

could just picture the kids’ faces.

“You do swim, don’t you, boy?” Uncle asked.

“I learned in the pool at the Chinatown Y up in the City.”

Uncle snorted in disgust. “That’s tame water. Nothing to see but

chlorine and the legs of other people kicking.” He nodded toward his

cove. “You take a place like this. Now that’s water.”

I held on to the railing. “It might be fun to swim here. If it’s okay.”

“Oh-kay.” Uncle made it sound like two separate words. “Next Saturday,

when you bring my food.” He gave an almost shy little smile.

Do you think that Craig will face up to the challenge Uncle Quail has

set for him? You can find out by reading the rest of Sea Glass. You

might also like to read two other books by Laurence Yep: Child of the

Owl, which is about a Chinese-American girl named Casey, and

Dragonwings, a story about a Chinese boy who goes to live with his

father in America.