Stories

The Boy Who Became a Wizard

from A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin

Earthsea is an imaginary world made up entirely of islands. On one of

these, the island of Gont, lives the boy Duny. Duny longs to be a mage,

or wizard, and he already has some magical powers. Now his magic is

about to be put to the test. The savage Kargs, from the Kargad Empire

which lies to the west, have sailed to invade Gont.

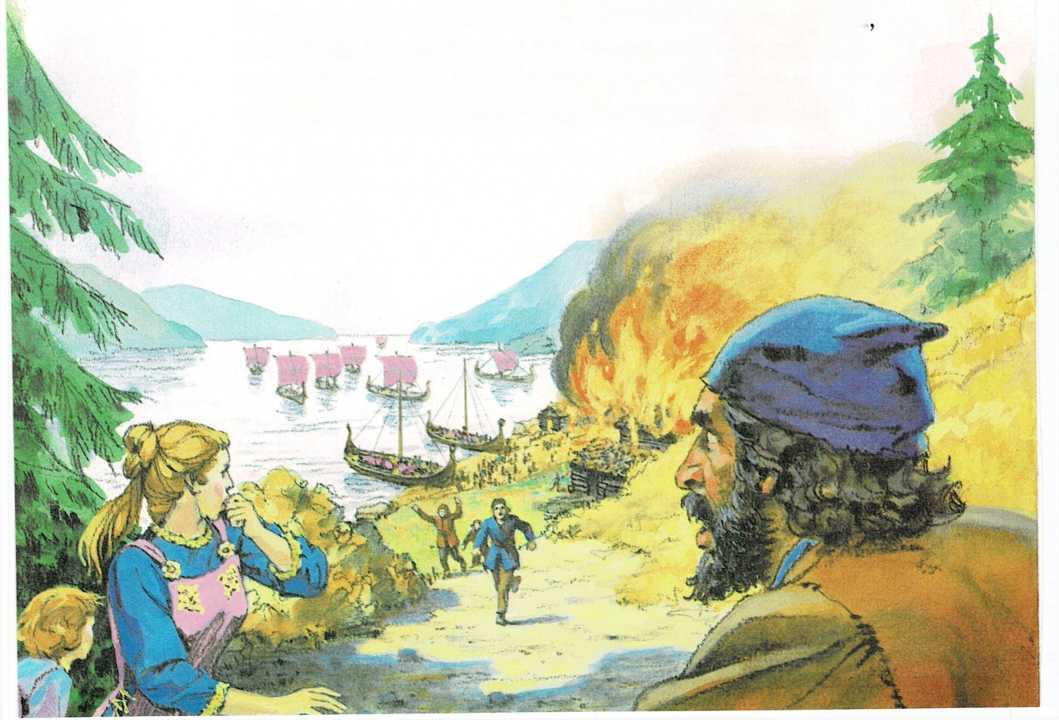

In those days the Kargad Empire was strong. Those are four great lands

that lie between the Northern and the Eastern Reaches: Karego-At, Atuan,

Hur-at-Hur,

Atnini. The tongue they speak there is not like any

spoken in the Archipelago or the other Reaches, and

they are a savage people, white-skinned, yellow-haired and fierce,

liking the sight of blood and the smell of burning towns. Last year

they had attacked the Torikles and the strong island Torheven, raiding

in

great force in fleets of red-sailed ships. News of this came north to

Gont, but the Lords of Gont were busy with their piracy and paid small

heed to the woes of other lands. Then Spevy fell to the Kargs and was

looted and laid waste, its people taken as slaves, so that even now it

is an isle of ruins. In lust of conquest the Kargs sailed next to Gont,

coming in a host, thirty great long ships, to East Port. They fought

through that town, took it, burned it; leaving their ships under guard

at the mouth of the River Ar they went up the Vale wrecking and looting,

slaughtering cattle and men. As they went they split into bands, and

each of these bands plundered where it chose. Fugitives brought warning

to the villages of the heights. Soon the people of Ten Alders saw smoke

darken the eastern sky, and that night those who climbed the High Fall

looked down on the Vale all hazed and red-streaked with fires where

fields ready for harvest had been set ablaze, and orchards burned, the

fruit roasting on the blazing boughs, and barns and farmhouses

smouldered in ruin.

Some of the villagers fled up the ravines and hid in the forest, and

some made ready to fight for their lives, and some did neither but stood

about lamenting. The witch was one who fled, hiding alone in a cave up

on the Kapperding Scarp and sealing the cave-mouth with spells. Duny’s

father the bronzesmith was one who stayed, for he would not leave his

smelting-pit and forge where he had worked for fifty years. All that

night he labored beating up what ready metal he had there into

spearpoints, and others worked with him binding these to the handles of

hoes and rakes, there being no time to make sockets and shaft them

properly. There had been no weapons in the village but hunting bows and

short knives, for the mountain folk of Gont are not warlike; it is not

warriors they are famous for, but goat-thieves, sea-pirates, and

wizards.

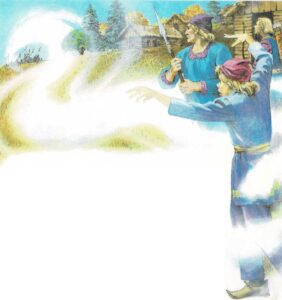

With sunrise came a thick white fog, as on many autumn mornings in the

heights of the island. Among their huts and houses down the straggling

street of Ten Alders the villagers stood waiting with their hunting bows

and new-forged spears, not knowing whether the Kargs might be far off or

very near, all silent, all peering into the fog that hid shapes and

distances and dangers from their eyes.

With them was Duny. He had worked all night at the forge-bellows,

pushing and pulling the two long sleeves of goathide that fed the fire

with a blast of air. Now his arms so ached and trembled from that work

that he could not hold out the spear he had chosen. He did not see how

he could fight or be of any good to himself or the villagers. It rankled

at his heart that he should die, spitted on a Kargish lance, while still

a boy: that he should go into the dark land without ever having known

his own name, his true name as a man. He looked down at his thin arms,

wet with cold fog-dew, and raged at his weakness, for he knew his

strength. There was power in him, if he knew how to use it, and he

sought among all the spells he knew for some device that might give him

and his companions an advantage, or at least a chance. But need alone is

not enough to set power free: there must be knowledge.

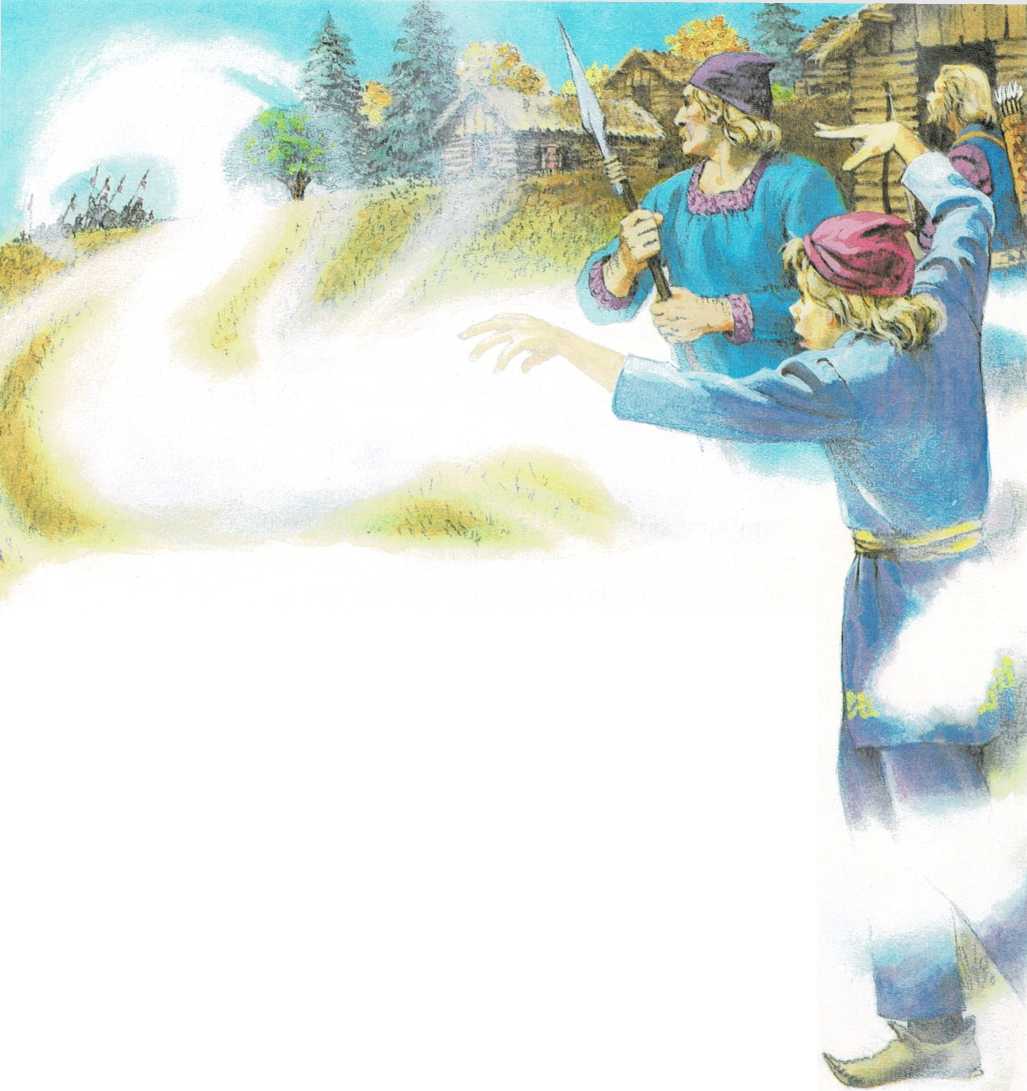

The fog was thinning now under the heat of the sun that shone bare above

on the peak in a bright sky. As the mists moved and parted in great

drifts and smoky wisps, the villagers saw a band of warriors coming up

the mountain. They were armored with bronze helmets and greaves and

breastplates of heavy leather and shields of wood and bronze, and armed

with swords and the long Kargish lance. Winding up along the steep bank

of the Ar they came in a plumed, clanking, straggling line, near enough

already that their white faces could be seen, and the words of their

jargon heard as they shouted to one another. In this band of the

invading horde there were about a hundred men, which is not many; but in

the village were only eighteen men and boys.

Now need called knowledge out: Duny, seeing the fog blow and thin across

the path before the Kargs, saw a spell that might avail him. An old

weatherworker of the Vale, seeking to win the boy as prentice, had

taught him several charms. One of these tricks was called fogweaving, a

binding-spell that gathers the mists together for a while in one place;

with it one skilled in illusion can shape the mist into fair ghostly

seemings, which last a little and fade away. The boy had no such skill,

but his intent was different, and he had the strength to turn the spell

into his own ends. Rapidly and aloud he named the places of the

boundaries of the village, and then spoke the fogweaving charm, but in

among its words he enlaced the words of a spell of concealment, and last

he cried the word that set the magic going.

Even as he did so his father coming up behind him struck him hard on the

side of the head, knocking him right down. “Be still, fool! keep your

blattering mouth shut, and hide if you can’t fight!”

Duny got to his feet. He could hear the Kargs now at the end of the

village, as near as the great yew tree

by the tanner’s yard. Their voices were clear, and the clink and creak

of their harness and arms, but they could not be seen. The fog had

closed and thickened all over the village, greying the light, blurring

the world till a man could hardly see his own hands before him.

“I’ve hidden us all,” Duny said, sullenly, for his head hurt from his

father’s blow, and the working of the doubled incantation had drained

his strength. “I’ll keep up this fog as long as I can. Get the others to

lead them up the High Fall.”

The smith stared at his son who stood wraithlike in that weird, dank

mist. It took him a minute to see Duny’s meaning, but when he did he ran

at once, noiselessly, knowing every fence and corner of the village, to

find the others and tell them what to do. Now through the grey fog

bloomed a blur of red, and the Kargs set fire to the thatch of a house.

Still they

did not come up into the village, but waited at the lower end till the

mist should lift and lay bare their loot and prey.

The tanner, whose house it was that burned, sent a couple of boys

skipping right under the Kargs’ noses, taunting and yelling and

vanishing again like smoke into smoke. Meantime the older men, creeping

behind fences and running from house to house, came close on the other

side and sent a volley of arrows and spears at the warriors, who stood

all in a bunch. One Karg fell writhing with a spear, still warm from its

forging, right through his body. Others were arrow-bitten, and all

enraged. They charged forward then to hew down their puny attackers, but

they found only the fog about them, full of voices. They followed the

voices, stabbing ahead into the mist with their great, plumed,

bloodstained lances. Up the length of the street they

came shouting, and never knew they had run right through the village, as

the empty huts and houses loomed and disappeared again in the writhing

grey fog. The villagers ran scattering, most of them keeping well ahead

since they knew the ground; but some, boys or old men, were slow. The

Kargs stumbling on them drove their lances or hacked with their swords,

yelling their war cry, the names of the White Godbrothers of Atuan:

“Wuluah! Atwah!”

Some of the band stopped when they felt the land grow rough underfoot,

but others pressed right on, seeking the phantom village, following dim

wavering shapes that fled just out of reach before them. All the mist

had come alive with these fleeing forms, dodging, flickering, fading on

every side. One group of the Kargs chased the wraiths straight to the

High Fall, the cliff’s edge above the springs of Ar, and the shapes they

pursued ran out onto the air and there vanished in a thinning of the

mist, while the pursuers fell screaming through fog and sudden sunlight

a hundred feet sheer to the shallow pools among the rocks. And those

that came behind and did not fall stood at the cliff’s edge, listening.

Now dread came into the Kargs’ hearts and they began to seek one

another, not the villagers, in the uncanny mist. They gathered on the

hillside, and yet always there were wraiths and ghost-shapes among them,

and other shapes that ran and stabbed from behind with spear or knife

and vanished again. The Kargs began to run, all of them, downhill,

stumbling, silent, until all at once they ran out from the grey blind

mist and saw the river and the ravines below the village all bare and

bright in morning sunlight. Then they stopped, gathering together, and

looked back. A wall of wavering, writhing grey lay blank across the

path, hiding all that lay behind it. Out from it burst two or three

stragglers, lunging and stumbling along, their long lances rocking on

their shoulders. Not one

Karg looked back more than that once. All went down, in haste, away from

the enchanted place.

Farther down the Northward Vale those warriors got their fill of

fighting. The towns of the East Forest, from Ovark to the coast, had

gathered their men and sent them against the invaders of Gont. Band

after band they came down from the hills, and that day and the next the

Kargs were harried back down to the beaches above East Port, where they

found their ships burnt; so they fought with their backs to the sea till

every man of them was killed, and the sands of Armouth were brown with

blood until the tide came in.

But on that morning in Ten Alders village and up on the High Fall, the

dank grey fog had clung a while, and then suddenly it blew and drifted

and melted away. This man and that stood up in the windy brightness of

the morning, and looked about him wondering. Here lay a dead Karg with

yellow hair long, loose, and bloody; there lay the village tanner,

killed in battle like a king.

Down in the village the house that had been set afire still blazed. They

ran to put the fire out, since their battle had been won. In the street,

near the great yew, they found Duny the bronzesmith’s son standing by

himself, bearing no hurt, but speechless and stupid like one stunned.

They were well aware of what he had done, and they led him into his

father’s house and went calling for the witch to come down out of her

cave and heal the lad who had saved their lives and their property, all

but four who were killed by the Kargs, and the one house that was burnt.

No weapon-hurt had come to the boy, but he would not speak nor eat nor

sleep; he seemed not to hear what was said to him, not to see those who

came to see him. There was none in those parts wizard enough to cure

what ailed him. His aunt said, “He has overspent his power,” but she had

no art to help him.

While he lay thus dark and dumb, the story of the lad who wove the fog

and scared off Kargish swordsmen with a mess of shadows was told all

down the Northward Vale, and in the East Forest, and high on the

mountain and over the mountain even in the Great Port of Gont. So it

happened that on the fifth day after the slaughter at Armouth a stranger

came into Ten Alders village, a man neither young nor old, who came

cloaked and bareheaded, lightly carrying a great staff of-oak that was

as tall as himself. He did not come up the course of the Ar like most

people, but down, out of the forests of the higher mountainside. The

village goodwives saw well that he was a wizard, and when he told them

that he was a heal-all, they brought him straight to the smith’s house.

Sending away all but the boy’s father and aunt the stranger stooped

above the cot where Duny lay staring into the dark, and did no more than

lay his hand on the boy’s forehead and touch his lips once.

Duny sat up slowly looking about him. In a little while he spoke, and

strength and hunger began to come back into him. They gave him a little

to drink and eat, and he lay back again, always watching the stranger

with dark wondering eyes.

The bronzesmith said to that stranger, “You are no common man.”

“Nor will this boy be a common man,” the other answered. “The tale of

his deed with the fog has come to Re Albi, which is my home. I have come

here to give him his name, if as they say he has not yet made his

passage into manhood.”

The witch whispered to the smith, “Brother, this must surely be the Mage

of Re Albi, Ogion the Silent, that one who tamed the earthquake—“

“Sir,” said the bronzesmith who would not let a great name daunt him,

“my son will be thirteen this month coming, but we thought to hold his

Passage at the feast of Sun-return this winter.”

“Let him be named as soon as may be,” said the mage, “for he needs his

name. I have other business now, but I will come back here for the day

you choose. If you see fit I will take him with me when I go thereafter.

And if he prove apt I will keep him as prentice, or see to it that he is

schooled as fits his gifts. For to keep dark the mind of the mageborn,

that is a dangerous thing.”

Very gently Ogion spoke, but with certainty, and even the hard-headed

smith assented to all he said.

On the day the boy was thirteen years old, a day in the early splendor

of autumn while still the bright leaves are on the trees, Ogion returned

to the village from his rovings over Gont Mountain, and the ceremony of

Passage was held. The witch took from the boy his name Duny, the name

his mother had given him as a baby. Nameless and naked he walked into

the cold springs of the Ar where it rises among rocks under the high

cliffs. As he entered the water clouds crossed the sun’s face and great

shadows slid and mingled over the water of the pool about him. He

crossed to the far bank, shuddering with cold but walking slow and erect

as he should through that icy, living water. As he came to the bank

Ogion, waiting, reached out his hand and clasping the boy’s arm

whispered to him his true name: Ged.

Thus was he given his name by one very wise in the uses of power.

The feasting was far from over, and all the villagers were making merry

with plenty to eat and beer to drink and a chanter from down the Vale

singing the Deed of the Dragonlords, when the mage spoke in his quiet

voice to Ged: “Come, lad. Bid your people farewell and leave them

feasting.”

Ged fetched what he had to carry, which was the good bronze knife his

father had forged him, and a leather coat the tanner’s widow had cut

down to his size, and an alderstick his aunt had becharmed for him:

that was all he owned besides his shirt and breeches. He said farewell

to them, all the people he knew in all the world, and looked about once

at the village that straggled and huddled there under the cliffs, over

the river-springs. Then he set off with his new master through the steep

slanting forests of the mountain isle, through the leaves and shadows of

bright autumn.

In the book, The Wizard of Earthsea, you can follow Ged to the School

for Wizards. You will also see what happens when, driven by pride and

jealousy, he uses his power too soon and unleashes a shadowy evil that

threatens all of Earthsea. The author, Ursula K. Le Guin, has written

two other books about the adventures of Ged that you will want to read:

Tombs of Atuan and *The Farthest Shore.