Nina Terrance

from The Cry of the Crow by Jean Craighead George

Mandy Tressel awakes to the sound of gun blasts. Her father or older

brothers, Jack and Carver, must be hunting crows in Piney Woods. Even

Drummer, her younger brother, can hardly wait until he is old enough to

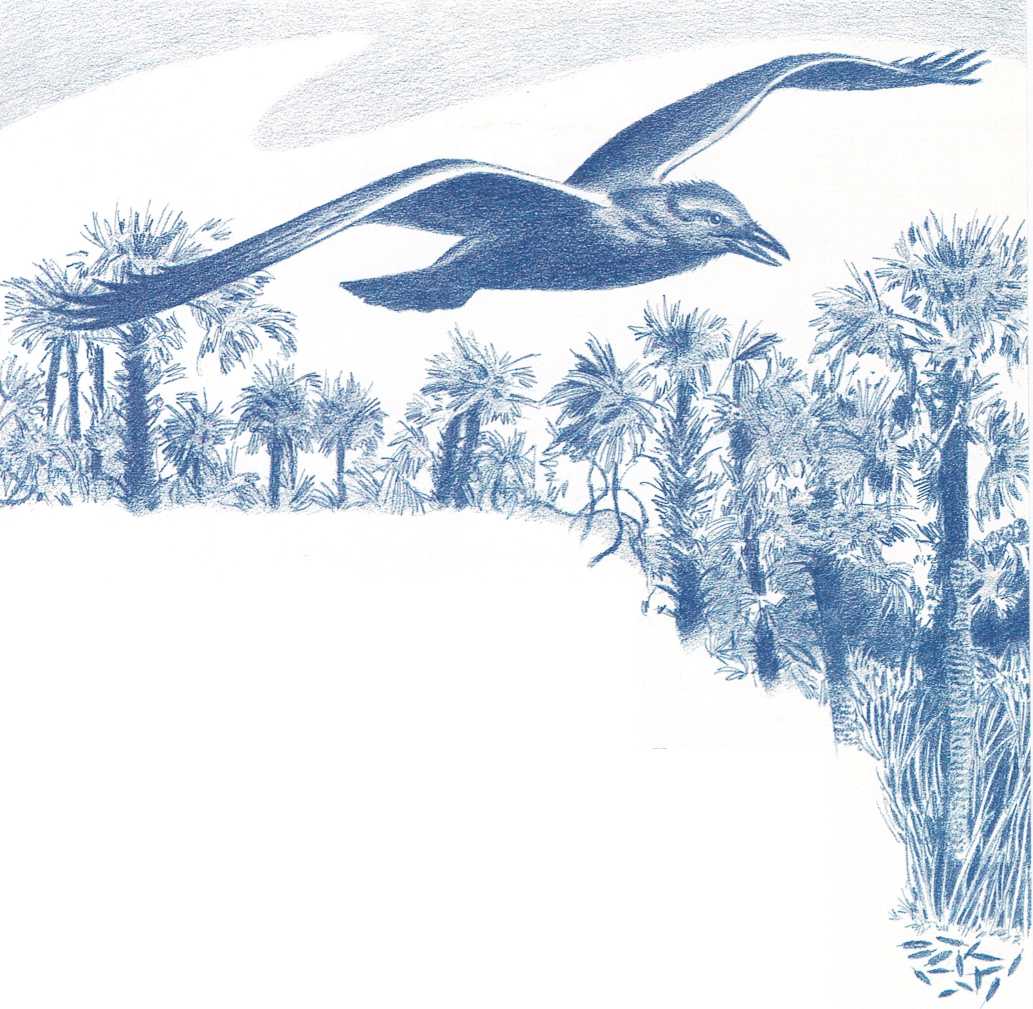

hunt. Later that day, Mandy finds an orphaned baby crow and names her

Nina Terrance. Determined to care for Nina, she makes a hidden nest on

the ground. Somehow, Mandy must keep her father and brothers from

finding her new pet.

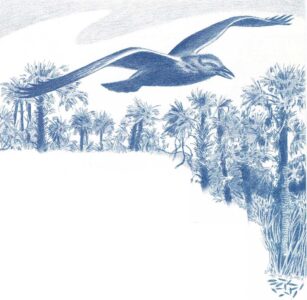

Later that afternoon Kray, the leader of the Trumpet Hammock crows, flew

over Piney Woods and, spotting black feathers on the ground, focused

acutely on them by rounding the curvature of his eye lens as crows do.

He dropped down on a tree limb near the skirted sable palm and stared.

Unlike people, who have one central point of sharp vision, birds have

two—one in the center of the retina and one in the rear. These,

.. together with his overall crow vision, gave Kray three simultaneous

views of the feathers, from each side and forward. What he saw said:

“murdered crow.”“Nevah, nevah,” he mourned. His cry traveled through the forest,

rolled out over the saw grass, and penetrated the dark niches and

hollows of Trumpet Hammock.

At the sound every crow froze where it was. It was as if none existed.

Extensions on stubs appeared, however, black knots on limbs, but no

crows. They had become one with the inanimate things of the forest.

Nina Terrance heard Kray’s doomsday pronouncement and looked at him

through a hole in the leaves. Her stomach pinched with hunger; her legs

wobbled from lack of nourishment. She needed only to cry the begging

note of the eyas crow and Kray, or any other nearby crow, would drop

down and feed the orphan, but she was rendered silent by his “sad crow”

cry.

Still eyeing the black feathers, Kray sidled along the limb, then walked

up a bough like a shadow. When he reached the top of the tree he spread

his wings. A wind gusted under them, lifted him, and carried him

sideways toward the hammock.

“Nevah, nevah,” he moaned once more, then called sharply, “Caia,” for

crows call “caw” when they are flying away from their roost, “caia” when

they are coming home.

An hour of silence passed, then the birds began to move again.

Nina Terrance turned her head. A beetle crept along the fingerlike edges

of one of the palm leaves that made her nest. She watched it, but she

was still unable to coordinate beak and eye to catch it. She had,

however, today fanned her wings for the first time. Yesterday she had

run her beak across her back feathers. Each day she could do one more

bird skill as she developed toward being a bird that could fly.

When at sunset Kray announced the end of the day with one clear “Caw,”

the eyas shook herself and nestled down in her Mandy-made nest. Her

hunger was unbearable. She closed her eyes and slowed down her breathing

to conserve energy.

Promptly at sunup, when she could see, she flopped to the edge of the

nest and prepared to fling herself to the ground and cry until the crows

of Trumpet Hammock came and fed her.

Crunch da dum. She could not move. The sound of the hunter’s footsteps

immobilized her. Crunch da dum, crunch da dum. Far away now, crunch

da dum.

The sun touched the top of the pines and Kray announced the start of the

day. His clan awoke and yawned, then silently preened their feathers to

make them airtight for flight. The eyases in well-hidden nests opened

their eyes. One was old enough to shake himself, three days more

advanced than Nina Terrance.

Presently an adult crow designated himself guard crow for the morning,

for the crows rotate this duty. He sailed to a stub on an old cypress

tree, where he scanned the river of grass, the distant highway, Waterway

Village, and the strawberry field. The berries matured later than most

of Florida’s strawberry crop, for they were a unique cross between a

wild strawberry of the north and the enormous cultivated berries of

Florida and California. Their flavor was piquant and sugar sweet, and

they were very much in demand in fancy restaurants. The guard crow did

not even glance at them. The “sad crow” call of yesterday had linked

death to the woods.

The door of the cinder-block house opened and Mandy came out. The guard

crow knew her as he did her mother. He considered them both harmless

“large rabbits” of the yard and paths and was unafraid of them.

“Caaa caa ca,” he called to the clan—a signal that meant disperse and

go hunt. One by one the crows flapped through the trees and coasted on

partially extended wings out across the Glades, then beat their way

toward the distant highway where they scouted for road kill. The guard

bird watched them go, flattening his eye lens to keep them in focus

three and four miles away. Then he glanced out of the back of his eyes

and scanned for enemies: snakes, rats, owls, hawks, anything that might

threaten the precious eyases.

When the crows were gone, the mockingbirds and wrens flew to their

singing posts and announced ownership of their part of the forest edge.

Nina Terrance was listening to them when she felt Mandy push back the

huge leaves and enter the sable palm tent.

“Hi, Nina Terrance,” she said. “I can’t stay long. I sneaked out of the

house before Daddy got up, to feed you and to make sure you’re all

right.” Cupping her hands, she lifted Nina out of her nest and placed

her on the ground. Dipping a piece of cheese sandwich in a jar of milk,

she held it out for Nina Terrance. The bird instantly recognized the

offering as food although she had never seen bread and cheese before.

She fluttered her wings and begged. Mandy stuffed her mouth and broke

off another bite.

As Nina Terrance ate she changed the shape of her eye lenses from flat

to round and back again. Then she blinked. Something was happening to

her mind. Mandy was becoming her mother and she, Nina Terrance, was

becoming Mandy. Her feathers in her bird mind were knitting into human

clothing, her head was becoming covered with brown hair, and her wings

were feeling like hands.

Mandy was being imprinted on her mind, because whoever feeds a baby bird

is stamped upon its brain as a parent, be it a mechanical toy bird or a

little girl. The bird thereafter considers itself to be like the toy or

the human.

By the end of the feeding Nina Terrance was looking with adoration at

her mother, whom she now thought she resembled. Her mother picked her

up, held her close, and after smelling her sweet feathers put her in the

nest.

“Stay still until I come back,” she said.

“Ay,” croaked Nina Terrance, fluttering her throat to effect an

imitation of her mother’s voice.

When Mandy reached home her father was at his desk in the living room

making notes in his account book. He struggled, head down, shoulders

rounded over the work, for Fred Tressel had never completed sixth grade

and arithmetic came hard to him. He was only comfortable when he was out

in the greenhouse or field crossbreeding his famous stock of

strawberries and, when a good strain came along, an occasional tomato or

pepper. Mandy’s mother, Barbara, often said Fred Tressel was related to

the pollinating bee.

Mandy paused on a dark step to watch this huge man who had grown up

planting vegetables and

fruits—and also hunting alligators until they were protected by the

National Park. When he smiled, which was most of the time, he did not

seem like a person who could shoot crows. Once Mandy had asked him why

he did it, and he had answered: “My family comes first. Our crops are

our living.”

This had not been a very satisfactory answer for Mandy because, one, she

had never seen a crow in the strawberry patch, and two, crows were small

and helpless like Nina Terrance.

She must ask him again, she thought as she crawled back into bed with

her clothes on and waited until she heard her father fixing his

breakfast in the kitchen below.

The clank of pans was her usual signal to get up. She arose, brushed her

hair, and listened as she did every morning to Jack and Carver shouting

in the shower and banging doors. In the cacophony of morning in the

Tressel home she ran down the stairs and hurried through the living room

and across the hall to her parents’ room.

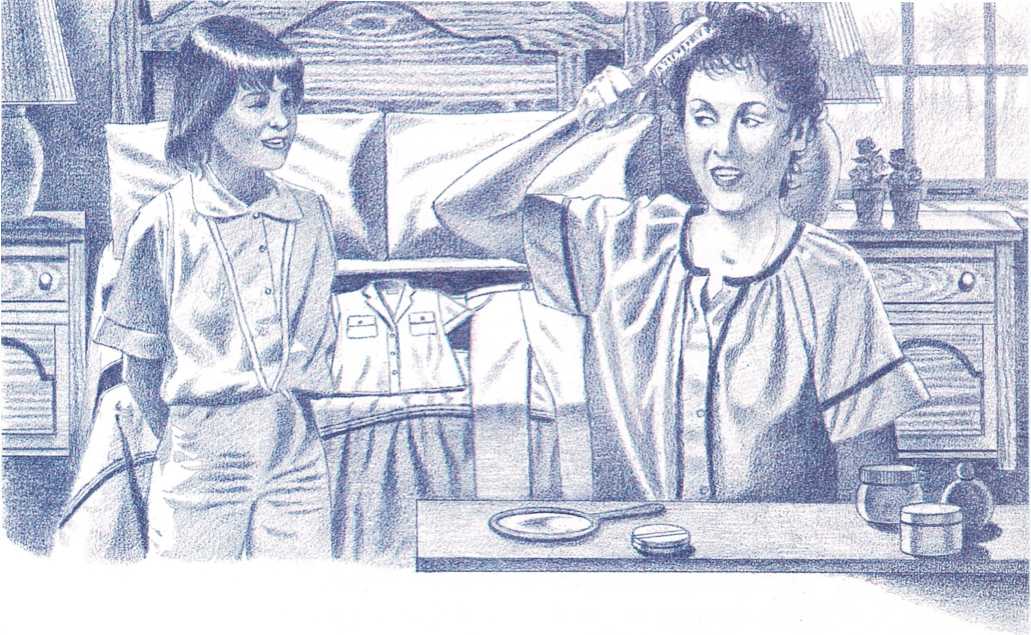

Her mother was seated at her dressing table brushing her short brown

hair and coaxing the front curls into waves.

“Hi, honey,” she said upon seeing Mandy in the mirror. “You look like

you’ve swallowed an alligator. What’s up?”

The door banged as her father went out to the strawberry field. Mandy

sat down on the bed and patted the green slacks and shirt her mother had

laid out for herself. She worked weekdays at the Agricultural Experiment

Station at the north end of town.

“I have a new friend,” she said.

“That’s wonderful. What’s her name?” Her mother peered closer at herself

and rubbed a freckle on her cheek.

“Nina Terrance.”

“That’s an interesting name. Is she Puerto Rican?” “No.”

“Too bad, I hoped maybe she could help me. Maria and Teresa will be

helping with the strawberry crop again and I can’t always understand

them.”

“You speak good Spanish, Mommy,” said Mandy, smoothing the collar of the

shirt on the bed.

“Well, I’m learning, but I could use help. And I hoped your new friend

…”

“Nina Terrance can’t possibly help,” Mandy said so forcibly that Barbara

looked again at her daughter’s reflection in the mirror.

“I just wondered if she could, that’s all. What color is your friend’s

hair?”

“Black.”

“And her eyes?”

“A pale milky blue.”

“Pale milky blue? Good heavens, Mandy, she sounds odd.” Barbara Tressel

slowly swung around on her stool and peered at her daughter. “What do

her parents do?” she asked suspiciously.

\’ “Fly.”

“They do? Where does she live?”

“In Piney Woods.”

“Oh, Mandy. Are you sure you should keep this friend?” Mandy slid off

the bed and walked to her mother’s side.

“Yes, Mommy. I am.”

“You know how your dad feels about crows?” She looked directly into

Mandy’s eyes. “I mean how he really feels about them.”

“Yes.”

“And you think you should go ahead with this?”

“I’ll keep her out of his sight in the woods.”

Barbara slowly brushed her hair.

“Where are her parents?”

“Dead. All the crows of Piney Woods are dead. Daddy and Jack and Carver

shot them all—all but Nina Terrance.”

Barbara winced.

“I think you ought to talk to your father about this. He might not be as

terrible as you think.”

“But he is. He shoots crows.”

“He also knows a lot about crows and might be able to help you. He says

crows are vindictive and remember forever the persons who shoot at them.

You wouldn’t want that crow hurting Daddy or Jack or Carver, would you?”

Mandy did not answer.

“Maybe your dad knows how to erase an imprint of a killer in a crow’s

mind. Then it wouldn’t hurt anyone.”

“How could a crow possibly hurt anyone? Nina Terrance is small and

gentle.”

Barbara shrugged and changed the subject.

“Have you written any more stories?”

Mandy was about to say no, then changed her mind.

“One. For The Waterway Times.\”

“Good. Are they going to run it?”

“No.”

“Shoot,” said Barbara with feeling. “Older brothers sure can be

difficult. I had three.”

Mandy’s head drooped, and she took her mother’s hand.

“Why won’t they let me be part of the newspaper? Drummer is and he’s

just a little boy.”

“I don’t know, Mandy. I really don’t know.” She ran her fingers through

Mandy’s hair. “But I think it is something about practicing being

dominant so they can compete out in the world. Soon Jack and Carver will

have to seek their fortunes, so to speak.”

“I do want to be a reporter for them. They have such a good time working

together on that paper.”

“Never mind, Mandy. You’re wonderful.”

“I’m not. I’m lonely. Loners don’t grow and learn. I’ll stay dumb.” She

slipped her arm around her mother and buried her face in her breast.

Barbara hugged her.

“But you have a remarkable friend now in Nina Terrance.”

Mandy blinked back her tears and smiled up at her mother.

“Nina Terrance attends a private school,” said Mandy.

“Wow, she must be rich.”

“Very rich. She has a favorite charity.”

“She does?” Barbara knitted her brow trying to figure out where the game

was leading.

“Yes, a poor family on the other side of Piney Woods.”

“Oh, I see,” Barbara nodded. “We must pack food boxes for them.”

“Exactly,” said Mandy, clapping her hands in the excitement of their

fantasy world. “And she can’t visit me. Her parents are very

protective.”

“Of course,” Barbara squeezed Mandy’s hand. “I would never have thought

of that.”

“I met her in the dentist’s office. She has braces too.”

“That’s getting pretty complicated. Do you have to have met her in the

dentist’s office?”

“I’ve already told Drummer I did.”

“Well, we had better stick with that. What else did you tell him about

her?”

“That’s all.” Mandy threw herself back on the bed again. “Except that

she’s rich and has a charity.”

“Good.” Barbara became silent as if weighing the wisdom of Mandy’s

keeping the crow.

“How can I tell which is the alarm cry?” Mandy had sensed her change of

heart and was trying to get her more involved. It worked.

“Watch old Kray, the boss bird that Drummer named,” Barbara said. “I

don’t know which one he is, but your daddy says when he or Jack or

Carver come near Trumpet Hammock, he gives the alarm cry and all his

clan vanishes from sight.”

“Does he give it when we come out?”

“No. He knows they hunt and kill crows and we don’t.” Barbara was

smiling helplessly at her daughter. “Mandy, I’m such a sucker for this.

Shall we pack a nice charity box for Nina Terrance’s poor family?”

“You’re going to play,” Mandy exclaimed happily. “Oh, Mommy, you’re

going to love Nina Terrance.”

“Yes, I’m afraid I am. Crows are fascinating, but you’ll have to keep

this one away from the farm.”

“I can do it.”

“Well, baby crows like to follow the parent that feeds them. You’ll have

to be clever. Doctor Bert, at the Experiment Station, is an expert on

crows, too. I’ll ask him what to do today and bring you some of the

bulletins he writes about their behavior and food habits. Crows are

social birds—that is, they live and work together like we people do.

They are very intelligent, too. Your dad says they can even count. If

three hunters go into a woods where a roost is, and two of them leave,

the crows won’t appear until the third hunter departs.”

“Daddy would want me to play with an intelligent friend, wouldn’t he?”

Barbara laughed and buttoned her shirt. “He certainly would.”

Mandy soon learns how clever her pet is—and how much trouble, too.

Read The Cry of the Crow to find out more about Nina Terrance and the

problems she creates. The author, Jean Craighead George, has written

many books about nature and wildlife, such as My Side of the Mountain

and Julie of the Wolves, which won the Newbery Medal.