Stories

I Strike the Jolly Roger

From Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

Treasure Island is one of the best adventure tales ever written. The

story, which takes place in the 1700’s, is told by young Jim Hawkins.

After Jim finds a map of buried treasure, the local squire and doctor

buy a ship, the Hispaniola, and hire a crew that includes the

one-legged Long John Silver as cook. When the ship reaches the island,

Silver and most of the crew (who are really pirates) mutiny and take

over the ship. Jim and his friends retreat to a small fort on the

island.

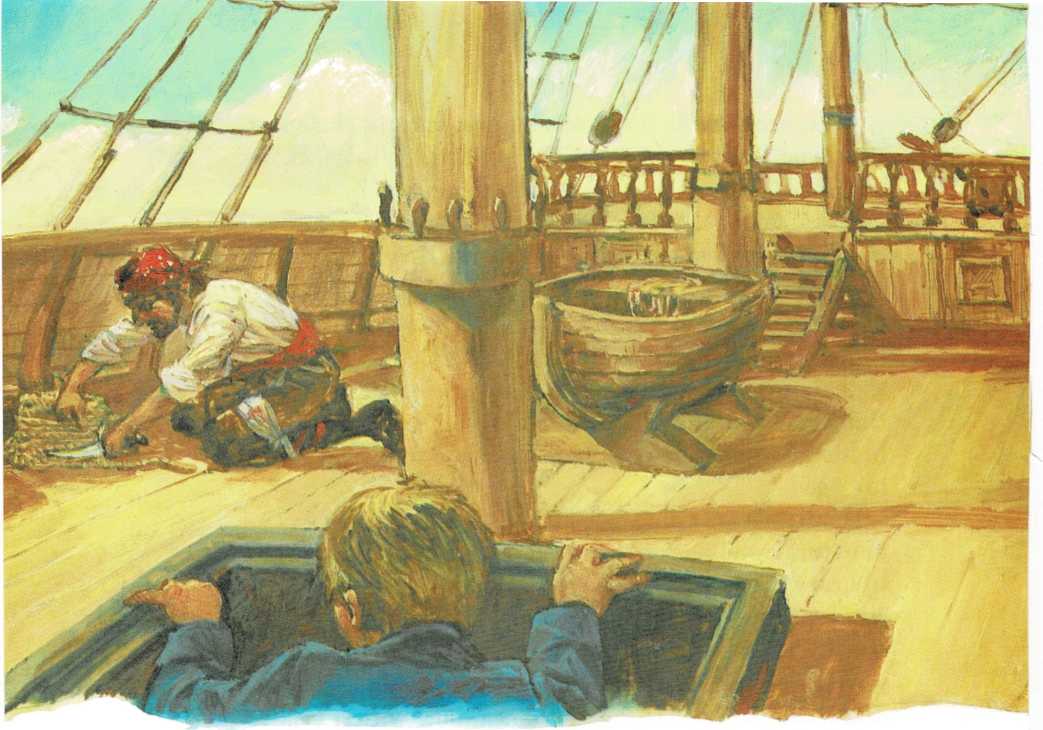

One night, when the pirates are ashore, Jim arms himself with two

pistols and slips out of the fort. He goes out to the Hispaniola in a

tiny boat and cuts the anchor cable so that the ship will drift ashore.

He then discovers that Israel Hands and another pirate, who wears a red

nightcap, are aboard. But they are drunk and fighting and don’t know

that the ship is adrift.

When he tries to return to shore, Jim’s tiny boat is caught by currents

and he drifts until daylight. Then he sees the Hispaniola, now under

sail. When he realizes that no one is steering the ship, he decides to

board her, which he does. But let Jim tell the rest—just as it

happened.

There were the two watchmen, sure enough: red-cap on his back, as stiff

as a handspike, with his arms stretched out like those of a crucifix,

and his teeth showing through his open lips; Israel Hands propped

against the bulwarks, his chin on his chest, his hands lying open before

him on the deck, his face as white, under its tan, as a tallow candle.

At every jump of the schooner, red-cap slipped to and fro; but—what

was ghastly to behold—neither his attitude nor his fixed

teeth-disclosing grin was anyway disturbed by this rough usage. At every

jump, too, Hands appeared still more to sink into himself and settle

down upon the deck, his feet sliding ever the farther out, and the whole

body canting towards the stern, so that his face became, little by

little, hid from me; and at last I could see nothing beyond his ear and

the frayed ringlet of one whisker.

At the same time, I observed, around both of them, splashes of dark

blood upon the planks, and began to feel sure that they had killed each

other in their drunken wrath.

While I was thus looking and wondering, in a calm moment, when the ship

was still, Israel Hands turned partly round, and, with a low moan,

writhed himself back to the position in which I had seen him first.

I walked aft until I reached the main-mast.

“Come aboard, Mr. Hands,” I said, ironically.

He rolled his eyes round heavily; but he was too far gone to express

surprise. All he could do was to utter one word, “Brandy.”

It occurred to me there was no time to lose; and, dodging the boom as it

once more lurched across the deck, I slipped aft, and down the companion

stairs into the cabin.

It was such a scene of confusion as you can hardly fancy. All the

lockfast places had been broken open in quest of the chart. The floor

was thick with mud, where ruffians had sat down to drink or consult

after wading in the marshes round their camp. The bulkheads, all painted

in clear white, and beaded round with gilt, bore a pattern of dirty

hands. Dozens of empty bottles clinked together in corners to the

rolling of the ship. One of the doctor’s medical books lay open on the

table, half of the leaves gutted out, I suppose, for pipelights. In the

midst of all this the lamp still cast a smoky glow, obscure and brown as

umber.

I went into the cellar; all the barrels were gone, and of the bottles a

most surprising number had been drunk out and thrown away. Certainly,

since the mutiny began, not a man of them could ever have been sober.

Foraging about, I found a bottle with some brandy left, for Hands; and

for myself I routed out some biscuit, some pickled fruits, a great bunch

of raisins, and a piece of cheese. With these I came on deck, put down

my own stock behind the rudder head, and well out of the coxswain’s[^9]

reach, went forward to the water-breaker, and had a good, deep drink of

water, and then, and not till then, gave Hands the brandy.

He must have drunk a gill before he took the bottle from his mouth.

“Aye,” said he, “by thunder, but I wanted some o’ that!”

I had sat down already in my own corner and begun to eat.

“Much hurt?” I asked him.

He grunted, or, rather, I might say, he barked.

“If that doctor was aboard,” he said, “I’d be right enough in a couple

of turns; but I don’t have no manner of luck, you see, and that’s what’s

the matter with me. As for that swab, he’s good and dead, he is,” he

added, indicating the man with the red cap. “He

warn’t no seaman, anyhow. And where mought you have come from?”

“Well,” said I, “I’ve come aboard to take possession of this ship, Mr.

Hands; and you’ll please regard me as your captain until further

notice.”

He looked at me sourly enough, but said nothing. Some of the colour had

come back into his cheeks, though he still looked very sick, and still

continued to slip out and settle down as the ship banged about.

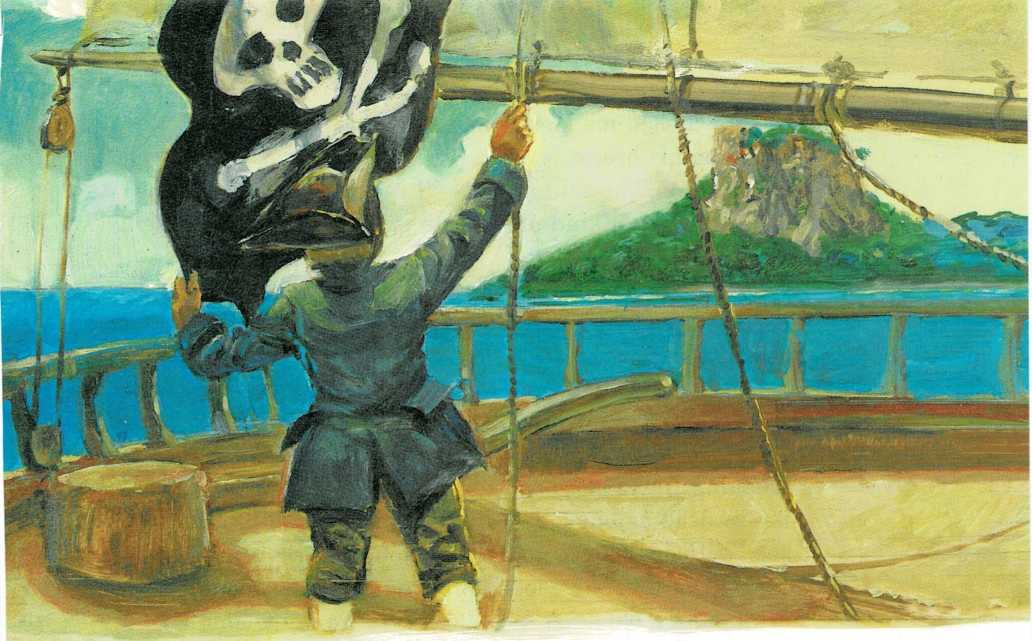

“By-the-by,” I continued, “I can’t have these colours, Mr. Hands; and,

by your leave, I’ll strike ’em.[^10] Better none than these.”

And, again dodging the boom, I ran to the colour lines, handed down

their cursed black flag, and chucked it overboard.

“God save the king!” said I, waving my cap; “and there’s an end to

Captain Silver!”

He watched me keenly and slyly, his chin all the while on his breast.

“I reckon,” he said at last—“I reckon, Cap’n Hawkins, you’ll kind of

want to get ashore, now. S’pose we talks.”

“Why, yes,” says I, “with all my heart, Mr. Hands. Say on.” And I went

back to my meal with a good appetite.

“This man,” he began, nodding feebly at the corpse—“O’Brien were his

name—a rank Irelander—this man and me got the canvas on her, meaning

for to sail her back. Well, he’s dead now, he is—as dead as bilge;

and who’s to sail this ship, I don’t see. Without I gives you a hint,

you ain’t that man, as far’s I can tell. Now, look here, you gives me

food and drink, and a old scarf or ankecher to tie my wound up, you do;

and I’ll tell you how to sail her; and that’s about square all round, I

take it.”

“I’ll tell you one thing,” says I: “I’m not going back to Captain Kidd’s

anchorage.[^11] [^12] I mean to get into North Inlet, and beach her

quietly there.”

“To be sure you did,” he cried. “Why, I ain’t sich an infernal lubber,

after all. I can see, can’t I? I’ve tried my fling, I have, and I’ve

lost, and it’s you has the wind of me. North Inlet? Why, I haven’t no

ch’ice, not I! I’d help you sail her up to Execution Dock,^1^ by

thunder! so I would.”

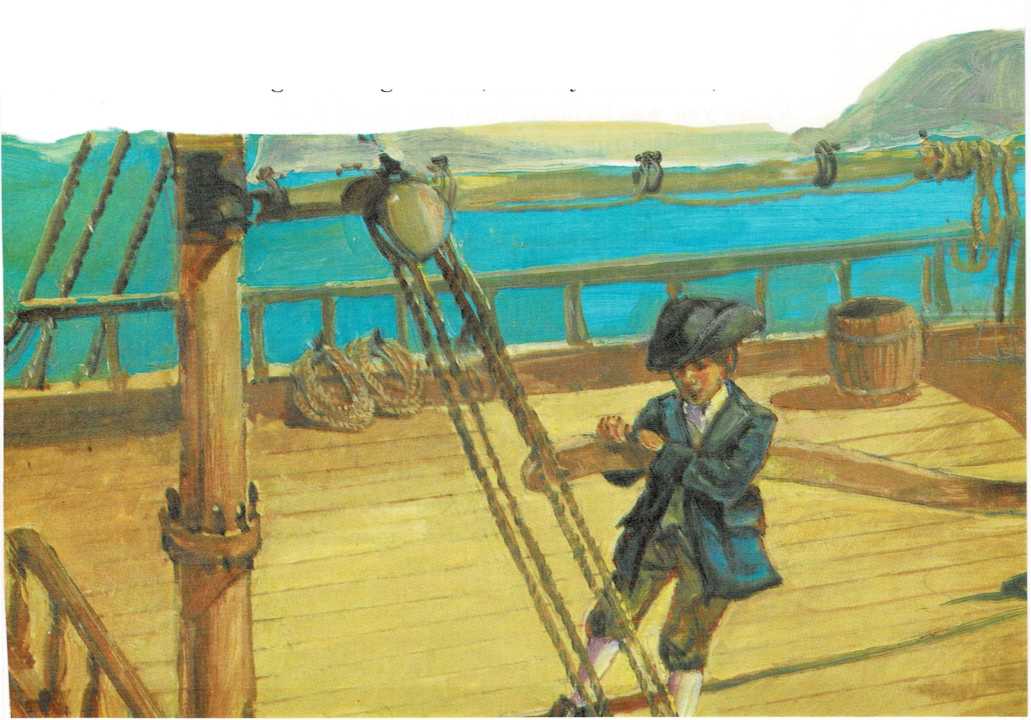

Well, as it seemed to me, there was some sense in this. We struck our

bargain on the spot. In three minutes I had the Hispaniola sailing

easily before the wind along the coast of Treasure Island, with good

hopes of turning the northern point ere noon, and

beating down again as far as North Inlet before high water, when we

might beach her safely, and wait till the subsiding tide permitted us to

land.

Then I lashed the tiller and went below to my own chest, where I got a

soft silk handkerchief of my mother’s. With this, and with my aid, Hands

bound up the great bleeding stab he had received in the thigh, and after

he had eaten a little and had a swallow or two more of the brandy, he

began to pick up visibly, sat straighter up, spoke louder and clearer,

and looked in every way another man.

The breeze served us admirably. We skimmed before it like a bird, the

coast of the island flashing by, and the view changing every minute.

Soon we were past the high lands and bowling beside low, sandy country,

sparsely dotted with dwarf pines, and soon we were beyond that again,

and had turned the corner of the rocky hill that ends the island on the

north.

I was greatly elated with my new command, and pleased with the bright,

sunshiny weather and these different prospects of the coast. I had now

plenty of water and good things to eat, and my conscience,

which had smitten me hard for my desertion, was quieted by the great

conquest I had made. I should, I think, have had nothing left me to

desire but for the eyes of the coxswain as they followed me derisively

about the deck, and the odd smile that appeared continually on his face.

It was a smile that had in it something both of pain and weakness—a

haggard, old man’s smile; but there was, besides that, a grin of

derision, a shadow of treachery in his expression as he craftily

watched, and watched, and watched me at my work.

The wind, serving us to a desire, now hauled into the west. We could run

so much the easier from the northeast corner of the island to the mouth

of the North Inlet. Only, as we had no power to anchor, and dared not

beach her till the tide had flowed a good deal farther, time hung on our

hands. The coxswain told me how to lay the ship to; after a good many

trials I succeeded, and we both sat in silence, over another meal.

“Cap’n,” said he, at length, with that same uncomfortable smile, “here’s

my old shipmate, O’Brien; s’pose you was to heave him overboard. I ain’t

partic’lar as a rule, and I don’t take no blame for settling his hash;

but I don’t reckon him ornamental, now, do you?”

“I’m not strong enough, and I don’t like the job; and there he lies for

me,” said I.

“This here’s an unlucky ship—this Hispaniola, Jim,” he went on,

blinking. “There’s a power of men been killed in this Hispaniola—a

sight o’ poor seamen dead and gone since you and me took ship to

Bristol. I never seen sich dirty luck, not I. There was this here

O’Brien, now—he’s dead, ain’t he? Well, now, I’m no scholar, and

you’re a lad as can read and figure; and, to put it straight, do you

take it as a dead man is dead for good, or do he come alive again?”

“You can kill the body, Mr. Hands, but not the spirit; you must know

that already,” I replied. “O’Brien there is in another world, and maybe

watching us.”

“Ah!” says he. “Well, that’s unfort’nate—appears as if killing parties

was a waste of time. Howsomever, sperrits don’t reckon for much, by what

I’ve seen. I’ll chance it with the sperrits, Jim. And now, you’ve spoke

up free, and I’ll take it kind if you’d step down into that there cabin

and get me a—well, a—shiver my timbers! I can’t hit the name on’t;

well, you get me a bottle of wine, Jim—this here brandy’s too strong

for my head.”

Now, the coxswain’s hesitation seemed to be unnatural; and as for the

notion of his preferring wine to brandy, I entirely disbelieved it. The

whole story was a pretext. He wanted me to leave the deck—so much was

plain; but with what purpose I could in no way imagine. His eyes never

met mine; they kept wandering to and fro, up and down, now with a look

to the sky, now with a flitting glance upon the dead O’Brien. All the

time he kept smiling, and putting his tongue out in the most guilty,

embarrassed manner, so that a child could have told that he was bent on

some deception. I was prompt with my answer, however, for I saw where my

advantage lay; and that with a fellow so densely stupid I could easily

conceal my suspicions to the end.

“Some wine?” said I. “Far better. Will you have white or red?”

“Well, I reckon it’s about the blessed same to me, shipmate,” he

replied; “so it’s strong, and plenty of it, what’s the odds?”

“All right,” I answered. “I’ll bring you port, Mr. Hands. But I’ll have

to dig for it.”

With that I scuttled down the companion with all the noise I could,

slipped off my shoes, ran quietly along the sparred gallery, mounted the

forecastle ladder, and

popped my head out of the fore companion. I knew he would not expect to

see me there; yet I took every precaution possible; and certainly the

worst of my suspicions proved too true.

He had risen from his position to his hands and knees; and, though his

leg obviously hurt him pretty sharply when he moved—for I could hear

him stifle a groan—yet it was at a good, rattling rate that he trailed

himself across the deck. In half a minute he had reached the port

scuppers, and picked, out of a coil of rope, a long knife, or rather a

short dirk, discoloured to the hilt with blood. He looked upon it for a

moment, thrusting forth his under jaw, tried the point upon his hand,

and then, hastily concealing it in the bosom of his jacket, trundled

back again into his old place against the bulwark.

This was all that I required to know. Israel could move about; he was

now armed; and if he had been at so much trouble to get rid of me, it

was plain that I was meant to be the victim. What he would do

afterwards—whether he would try to crawl right across the island from

North Inlet to the camp among the swamps, or whether he would fire Long

Torn,^0^ trusting that his own comrades might come first to help him,

was, of course, more than I could say.

Yet I felt sure that I could trust him in one point, since in that our

interests jumped together, and that was in the disposition of the

schooner. We both desired to have her stranded safe enough, in a

sheltered place, and so that, when the time came, she could be got off

again with as little labour and danger as might be; and until that was

done I considered that my life would certainly be spared.

While I was thus turning the business over in my mind, I had not been

idle with my body. I had stolen back to the cabin, slipped once more

into my shoes, and laid my hand at random on a bottle of wine, and now,

with this for an excuse, I made my reappearance on the deck.

Hands lay as I had left him, all fallen together in a bundle, and with

his eyelids lowered, as though he were too weak to bear the light. He

looked up, however, at my coming, knocked the neck off the bottle, like

a man who had done the same thing often, and took a good swig, with his

favourite toast of “Here’s luck!” Then he lay quiet for a little, and

then, pulling out a stick of tobacco, begged me to cut him a quid.

“Cut me a junk o’ that,” says he, “for I haven’t no knife, and hardly

strength enough, so be as I had. Ah,

- “Long Tom” was the name given the single small cannon that the ship

carried.

Jim, Jim, I reckon I’ve missed stays! Cut me a quid, as’ll likely be the

last, lad; for I’m for my long home, and no mistake.”

“Well,” said I, “I’ll cut you some tobacco; but if I was you and thought

myself so badly, I would go to my prayers, like a Christian man.”

“Why?” said he. “Now, you tell me why.”

“Why?” I cried. “You were asking me just now about the dead. You’ve

broken your trust; you’ve lived in sin and lies and blood; there’s a man

you killed lying at your feet this moment; and you ask me why! For God’s

mercy, Mr. Hands, that’s why.”

I spoke with a little heat, thinking of the bloody dirk he had hidden in

his pocket, and designed, in his ill thoughts, to end me with. He, for

his part, took a great draught of the wine, and spoke with the most

unusual solemnity.

“For thirty years,” he said, “I’ve sailed the seas, and seen good and

bad, better and worse, fair weather and foul, provisions running out,

knives going, and what not. Well, now I tell you, I never seen good come

o’ goodness yet. Him as strikes first is my fancy; dead men don’t bite;

them’s my views—amen, so be it. And now, you look here,” he added,

suddenly changing his tone, “we’ve had about enough of this foolery. The

tide’s made good enough by now. You just take my orders, Cap’n Hawkins,

and we’ll sail slap in and be done with it.”

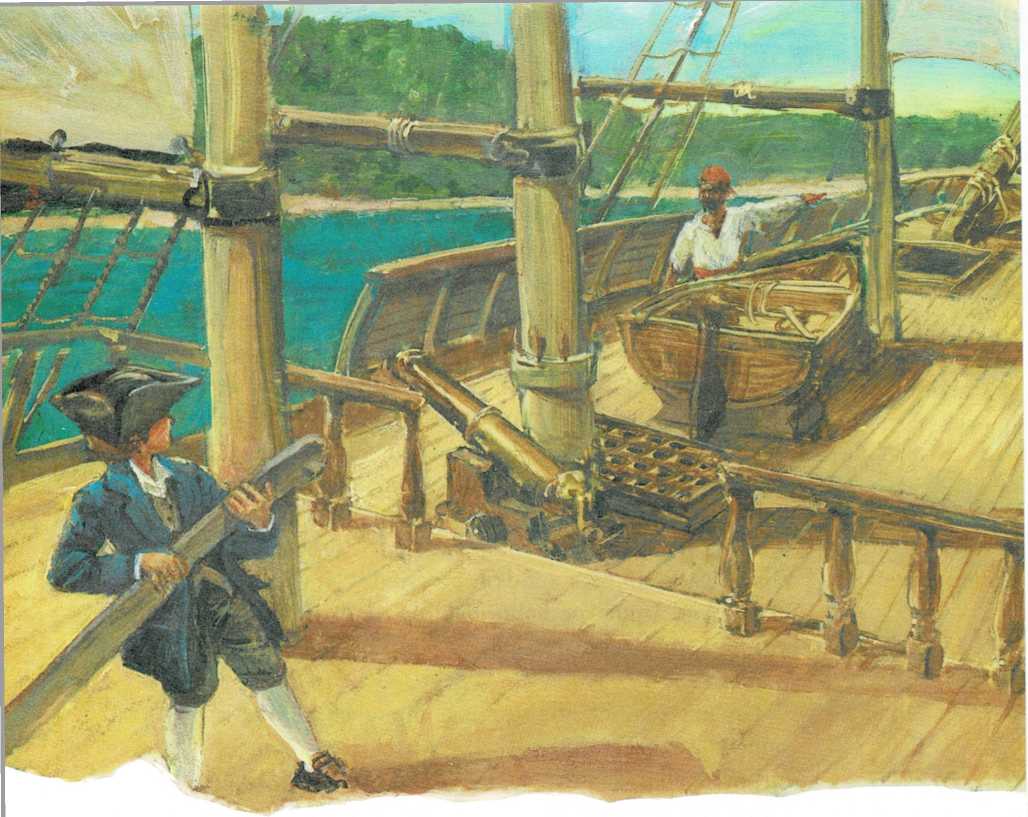

All told, we had scarce two miles to run; but the navigation was

delicate, the entrance to this northern anchorage was not only narrow

and shoal, but lay east and west, so that the schooner must be nicely

handled to be got in. I think I was a good, prompt subaltern, and I am

very sure that Hands was an excellent pilot; for we went about and

about, and dodged in, shaving the banks, with a certainty and a neatness

that were a pleasure to behold.

Scarcely had we passed the heads before the land closed around us. The

shores of North Inlet were as thickly wooded as those of the southern

anchorage; but the space was longer and narrower, and more like, what in

truth it was, the estuary of a river. Right before us, at the southern

end, we saw the wreck of a ship in the last stages of dilapidation. It

had been a great vessel of three masts, but had lain so long exposed to

the injuries of the weather, that it was hung about with great webs of

dripping seaweed, and on the deck of it shore bushes had taken root, and

now flourished thick with flowers. It was a sad sight, but it showed us

that the anchorage was calm.

“Now,” said Hands, “look there; there’s a pet bit for to beach a ship

in. Fine flat sand, never a catspaw, trees all around of it, and flowers

a-blowing like a garding on that old ship.”

“And once beached,” I inquired, “how shall we get her off again?”

“Why, so,” he replied: “you take a line ashore there on the other side

at low water: take a turn about one o’ them big pines; bring it back,

take a turn round the capstan, and lie-to for the tide. Come high water,

all hands take a pull upon the line, and off she comes as sweet as

natur’. And now, boy, you stand by. We’re near the bit now, and she’s

too much way on her. Starboard a

little—so—steady—starboard—larboard a little—steady—steady!”

So he issued his commands, which I breathlessly obeyed; till, all of a

sudden, he cried, “Now, my hearty, luff!” And I put the helm hard up,

and the Hispaniola swung round rapidly, and ran stem on for the low

wooded shore.

The excitement of these last manoeuvres had somewhat interfered with the

watch I had kept hitherto, sharply enough, upon the coxswain. Even then

I was still so much interested, waiting for the ship to touch, that I

had quite forgot the peril that hung over my head, and stood craning

over the starboard bulwarks and watching the ripples spreading wide

before the bows. I might have fallen without a struggle for my life, had

not a sudden disquietude seized upon me, and made me turn my head.

Perhaps I had heard a creak, or seen his shadow moving with the tail of

my eye; perhaps it was an instinct like a cat’s; but, sure enough, when

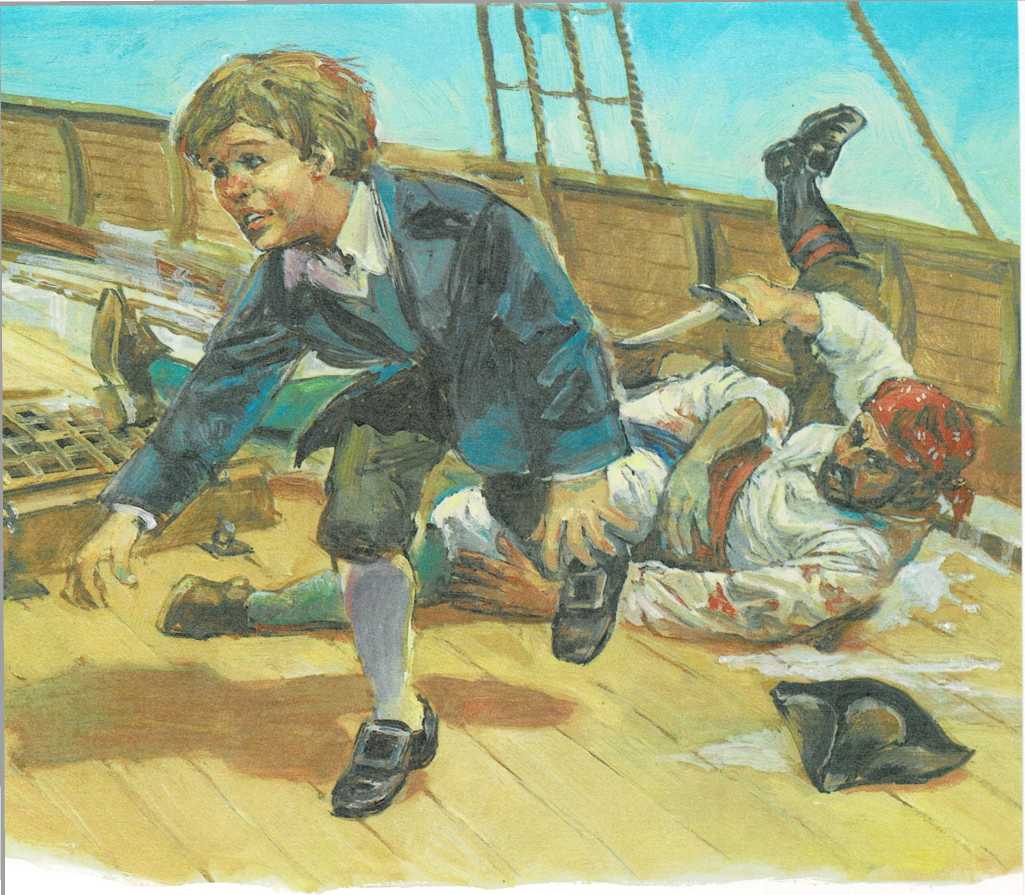

I looked round, there was Hands, already half-way towards me, with the

dirk in his right hand.

We must both have cried out aloud when our eyes met; but while mine was

the shrill cry of terror, his was a roar of fury like a charging bull’s.

At the same instant he threw himself forward, and I leaped

sideways towards the bows. As I did so, I let go of the tiller, which

sprang sharp to leeward; and I think this saved my life, for it struck

Hands across the chest, and stopped him, for the moment, dead.

there followed neither flash nor sound; the priming was useless with

sea-water. I cursed myself for my neglect. Why had not I, long before,

reprimed and

Before he could recover, I was safe out of the corner where he had me

trapped, with all the deck to dodge about. Just forward of the main-mast

I stopped, drew a pistol from my pocket, took a cool aim, though he had

already turned and was once more coming directly after me, and drew the

trigger. The hammer fell, but reloaded my only weapons? Then I should

not have been as now, a mere fleeing sheep before this butcher.

Wounded as he was, it was wonderful how fast he could move, his grizzled

hair tumbling over his face, and his face itself as red as a red ensign

with his haste and fury. I had no time to try my other pistol,

nor, indeed, much inclination, for I was sure it would be useless. One

thing I saw plainly: I must not simply retreat before him, or he would

speedily hold me boxed into the bows, as a moment since he had so nearly

boxed me in the stern. Once so caught, and nine or ten inches of the

blood-stained dirk would be my last experience on this side of eternity.

I placed my palms against the main-mast, which was of a goodish bigness,

and waited, every nerve upon the stretch.

Seeing that I meant to dodge, he also paused; and a moment or two passed

in feints on his part, and corresponding movements upon mine. It was

such a game as I had often played at home about the rocks of Black Hill

Cove; but never before, you may be sure, with such a wildly beating

heart as now. Still, as I say, it was a boy’s game, and I thought I

could hold my own at it, against an elderly seaman with a wounded thigh.

Indeed, my courage had begun to rise so high, that I allowed myself a

few darting thoughts on what would be the end of the affair; and while I

saw certainly that I could spin it out for long, I saw no hope of any

ultimate escape.

Well, while things stood thus, suddenly the Hispaniola struck,

staggered, ground for an instant in the sand, and then, swift as a blow,

canted over to the port side, till the deck stood at an angle of

forty-five degrees, and about a puncheon*’ of water splashed into the

scupper holes, and lay, in a pool, between the deck and bulwark.

We were both of us capsized in a second, and both of us rolled, almost

together, into the scuppers; the dead red-cap, with his arms still

spread out, tumbling stiffly after us. So near were we, indeed, that my

head came against the coxswain’s foot with a crack that made my teeth

rattle. Blow and all, I was the first afoot again; for Hands had got

involved with the dead body. The sudden canting of the ship had made the

deck no place

- A puncheon [(puhn]{.smallcaps} chuhn) is a large cask, and also a

unit of measure equal to 84 gallons (318 liters).

for running on; I had to find some new way of escape, and that upon the

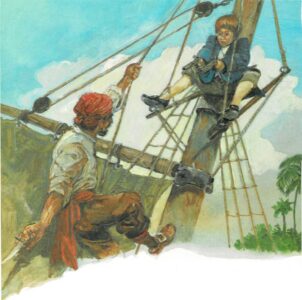

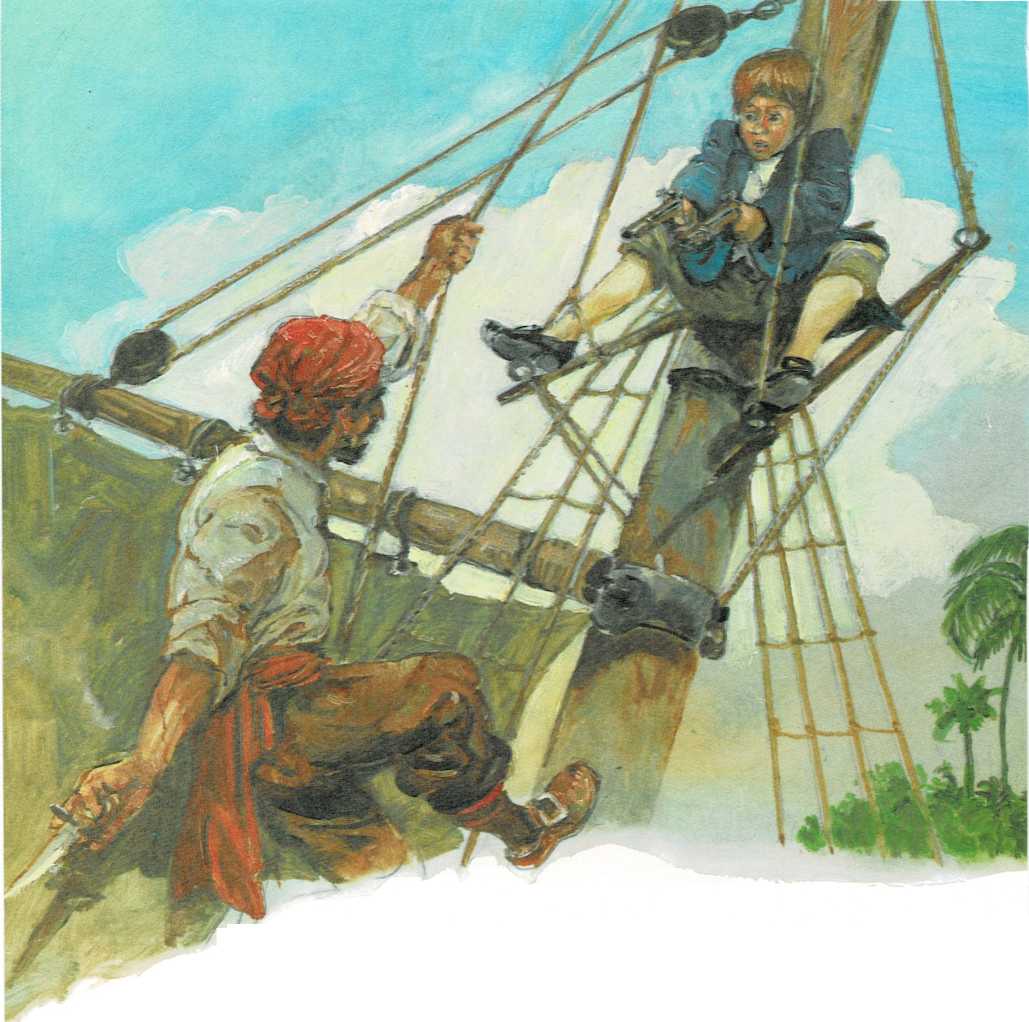

instant, for my foe was almost touching me. Quick as thought, I sprang

into the mizzen shrouds, rattled up hand over hand, and did not draw a

breath till I was seated on the cross-trees.

I had been saved by being prompt; the dirk had struck not half a foot

below me, as I pursued my upward flight; and there stood Israel Hands

with his mouth open and his face upturned to mine, a perfect statue of

surprise and disappointment.

Now that I had a moment to myself, I lost no time in changing the

priming of my pistol, and then, having

one ready for service, and to make assurance doubly sure, I proceeded

to draw the load of the other, andrecharge it afresh from the beginning.

My new employment struck Hands all of a heap; he began to see the dice

going against him; and, after an

obvious hesitation, he also hauled himself heavily into the shrouds,

and, with the dirk in his teeth, began slowly and painfully to mount. It

cost him no end of time and groans to haul his wounded leg behind him;

and I had quietly finished my arrangements before he was much more than

a third of the way up. Then, with a pistol in either hand, I addressed

him.

“One more step, Mr. Hands,” said I, “and I’ll blow your brains out! Dead

men don’t bite, you know,” I added, with a chuckle.

He stopped instantly. I could see by the working of his face that he was

trying to think, and the process was so slow and laborious that, in my

new-found security, I laughed aloud. At last, with a swallow or two, he

spoke, his face still wearing the same expression of extreme perplexity.

In order to speak he had to take the dagger from his mouth, but, in all

else, he remained unmoved.

“Jim,” says he, “I reckon we’re fouled, you and me, and we’ll have to

sign articles. I’d have had you but for that there lurch: but I don’t

have no luck, not I; and I reckon I’ll have to strike, which comes hard,

you see, for a master mariner to a ship’s younker like you, Jim.”

I was drinking in his words and smiling away, as conceited as a cock

upon a wall, when, all in a breath, back went his right hand over his

shoulder. Something sang like an arrow through the air; I felt a blow

and then a sharp pang, and there I was pinned by the shoulder to the

mast. In the horrid pain and surprise of the moment—I scarce can say

it was by my own volition, and I am sure it was without a conscious

aim—both my pistols went off, and both escaped out of my hands. They

did not fall alone; with a choked cry, the coxswain loosed his grasp

upon the shrouds, and plunged head first into the water.

If this small part of Treasure Island has given you a taste for

adventure, read the whole book. It is excitement from beginning to end.

And then you might try Silver’s Revenge by Robert Leeson, which is all

about what happened to those few who survived the voyage of the

Hispaniola.