I Leave the Island

from Island of the Blue Dolphins by Scott O’Dell

The book from which this story is taken is based on historical facts.

When a ship comes to take a small band of Indians to the mainland,

twelve-year-old Karana is left behind. She is certain the ship will turn

back for her, but it does not. Except for a pack of wild dogs, she is

alone.

sk sk

Summer is the best time on the Island of the Blue Dolphins. The sun is

warm then and the winds blow milder out of the west, sometimes out of

the south.

It was during these days that the ship might return and now I spent most

of my time on the rock, looking out from the high headland into the

east, toward the country where my people had gone, across the sea that

was never-ending.

Once while I watched I saw a small object which I took to be the ship,

but a stream of water rose from it and I knew that it was a whale

spouting. During those summer days I saw nothing else.

The first storm of winter ended my hopes. If the white men’s ship were

coming for me it would have come during the time of good weather. Now I

would have to wait until winter was gone, maybe longer.

The thought of being alone on the island while so many suns rose from

the sea and went slowly back into the sea filled my heart with

loneliness. I had not felt so lonely before because I was sure that the

ship would return as Matasaip had said it would. Now my hopes were dead.

Now I was really alone. I could not eat much, nor could I sleep without

dreaming terrible dreams.

The storm blew out of the north, sending big waves against the island

and winds so strong that I was

unable to stay on the rock. I moved my bed to the foot of the rock and

for protection kept a fire going throughout the night. I slept there

five times. The first night the dogs came and stood outside the ring

made by the fire. I killed three of them with arrows, but not the

leader, and they did not come again.

On the sixth day, when the storm had ended, I went to the place where

the canoes had been hidden, and let myself down over the cliff. This

part of the shore was sheltered from the wind and I found the canoes

just as they had been left. The dried food was still good, but the water

was stale, so I went back to the spring and filled a fresh basket.

I had decided during the days of the storm, when I had given up hope of

seeing the ship, that I would take one of the canoes and go to the

country that lay

toward the east. I remember how Kimki, before he had gone, had asked the

advice of his ancestors who had lived many ages in the past, who had

come to the island from that country, and likewise the advice of Zuma,

the medicine man who held power over the wind and the seas. But these

things I could not do, for Zuma had been killed by the Aleuts, and in

all my life I had never been able to speak with the dead, though many

times I had tried.

Yet I cannot say that I was really afraid as I stood there on the shore.

I knew^T^ that my ancestors had crossed the sea in their canoes, coming

from that place which lay beyond. Kimki, too, had crossed the sea. I was

not nearly so skilled with a canoe as these men, but I must say that

whatever might befall me on the endless waters did not trouble me. It

meant far less than the thought of staying on the island alone, without

a home or companions, pursued by wild dogs, where everything reminded me

of those who were dead and those who had gone away.

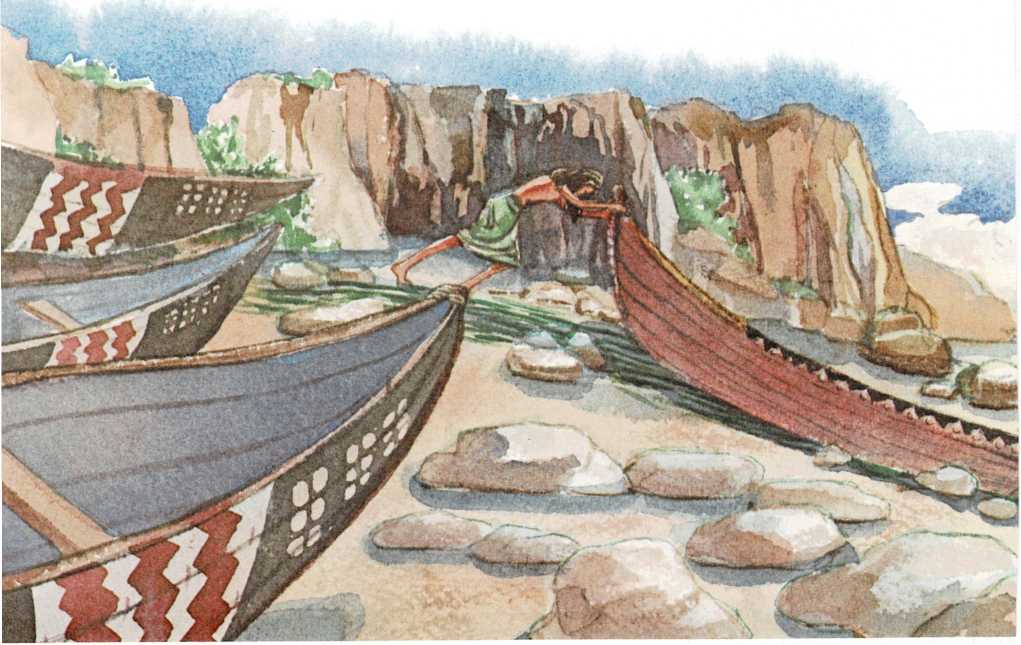

Of the four canoes stored there against the cliff, I chose the smallest,

which was still very heavy because it could carry six people. The task

that faced me was to push it down the rocky shore and into the water, a

distance four or five times its length.

This I did by first removing all the large rocks in front of the canoe.

I then filled in all these holes with pebbles and along this path laid

down long strips of kelp, making a slippery bed. The shore was steep and

once I got the canoe to move with its own weight, it slid down the path

and into the water.

The sun was in the west when I left the shore. The sea was calm behind

the high cliffs. Using the two-bladed paddle I quickly skirted the south

part of the island. As I reached the sandspit the wind struck. I was

paddling from the back of the canoe because you can go faster kneeling

there, but I could not handle it in the wind.

Kneeling in the middle of the canoe, I paddled hard and did not pause

until I had gone through the tides that run fast around the sandspit.

There were many small waves and I was soon wet, but as I came out from

behind the spit the spray lessened and the waves grew long and rolling.

Though it would have been easier to go the way they slanted, this would

have taken me in the wrong direction. I therefore kept them on my left

hand, as well as the island, which grew smaller and smaller, behind me.

At dusk I looked back. The Island of the Blue Dolphins had disappeared.

This was the first time that I felt afraid.

There were only hills and valleys of water around me now. When I was in

a valley I could see nothing and when the canoe rose out of it, only the

ocean stretching away and away.

Night fell and I drank from the basket. The water cooled my throat.

The sea was black and there was no difference between it and the sky.

The waves made no sound among themselves, only faint noises as they went

under the canoe or struck against it. Sometimes the noises seemed angry

and at other times like people laughing. I was not hungry because of my

fear.

The first star made me feel less afraid. It came out low in the sky and

it was in front of me, toward the east. Other stars began to appear all

around, but it was this one I kept my gaze upon. It was in the figure

that we call a serpent, a star which shone green and which I knew. Now

and then it was hidden by mist, yet it always came out brightly again.

Without this star I would have been lost, for the waves never changed.

They came always from the same direction and in a manner that kept

pushing me away from the place I wanted to reach. For this reason the

canoe made a path in the black water like a snake. But somehow I kept

moving toward the star which shone in the east.

This star rose high and then I kept the North Star on my left hand, the

one we call “the star that does not move.” The wind grew quiet. Since it

always died down when the night was half over, I knew how long I had

been traveling and how far away the dawn was.

About this time I found that the canoe was leaking. Before dark I had

emptied one of the baskets in which food was stored and used it to dip

out the water that came over the sides. The water that now moved around

my knees was not from the waves.

I stopped paddling and worked with the basket until the bottom of the

canoe was almost dry. Then I searched around, feeling in the dark along

the smooth planks, and found the place near the bow where the water was

seeping through a crack as long as my hand and the width of a finger.

Most of the time it was out of the sea, but it leaked whenever the canoe

dipped forward in the waves.

The places between the planks were filled with black pitch which we

gather along the shore. Lacking this, I tore a piece of fiber from my

skirt and pressed it into the crack, which held back the water.

Dawn broke in a clear sky and as the sun came out of the waves I saw

that it was far off on my left. During the night I had drifted south of

the place I wished to go, so I changed my direction and paddled along

the path made by the rising sun.

There was no wind on this morning and the long waves went quietly under

the canoe. I therefore moved faster than during the night.

I was very tired, but more hopeful than I had been since I left the

island. If the good weather did not change I would cover many leagues

before dark. Another night and another day might bring me within sight

of the shore toward which I was going.

Not long after dawn, while I was thinking of this strange place and what

it would look like, the canoe began to leak again. This crack was

between the same planks, but was a larger one and close to where I was

kneeling.

The fiber I tore from my skirt and pushed into the crack held back most

of the water which seeped in whenever the canoe rose and fell with the

waves. Yet I could see that the planks were weak from one end to the

other, probably from the canoe being stored so long in the sun, and that

they might open along their whole length if the waves grew rougher.

It was suddenly clear to me that it was dangerous to go on. The voyage

would take two more days, perhaps longer. By turning back to the island

I would not have nearly so far to travel.

Still I could not make up my mind to do so. The sea was calm and I had

come far. The thought of turning back after all this labor was more than

I could bear. Even greater was the thought of the deserted island I

would return to, of living there alone and forgotten. For how many suns

and how many moons?

The canoe drifted idly on the calm sea while these thoughts went over

and over in my mind, but when I saw the water seeping through the crack

again, I picked up the paddle. There was no choice except to turn back

toward the island.

I knew that only by the best of fortune would I ever reach it.

The wind did not blow until the sun was overhead. Before that time I

covered a good distance, pausing only when it was necessary to dip water

from the canoe. With the wind I went more slowly and had to stop more

often because of the water spilling over the sides, but the leak did not

grow worse.

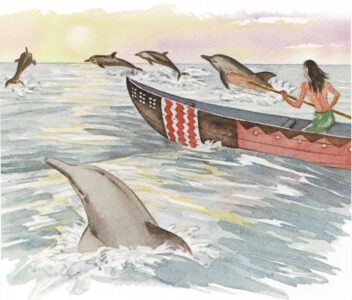

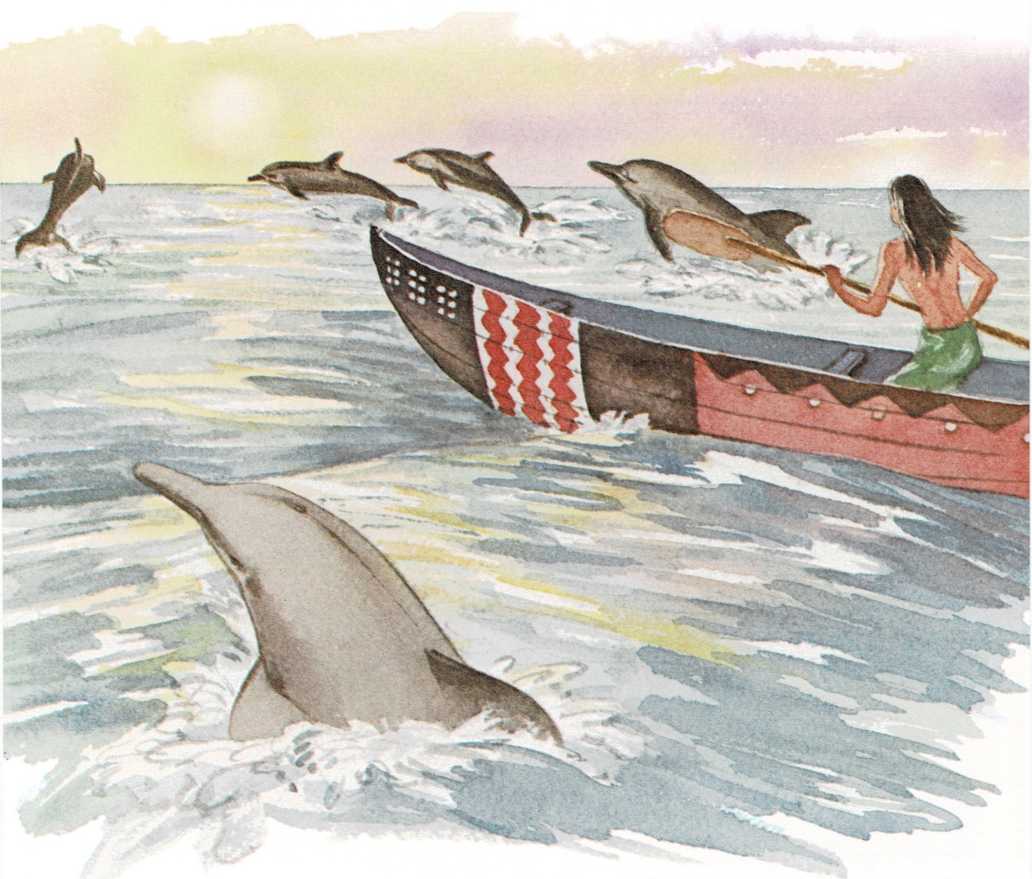

This was my first good fortune. The next was when a swarm of dolphins

appeared. They came swimming out of the west, but as they saw the canoe

they turned around in a great circle and began to follow me. They swam

up slowly and so close that I could see their eyes, which are large and

the color of the ocean. Then they swam on ahead of the canoe, crossing

back and forth in front of it, diving in and out, as if they were

weaving a piece of cloth with their broad snouts.

Dolphins are animals of good omen. It made me happy to have them

swimming around the canoe, and though my hands had begun to bleed from

the chafing of the paddle, just watching them made me forget the pain. I

was very lonely before they appeared, but now I felt that I had friends

with me and did not feel the same.

The blue dolphins left me shortly before dusk. They left as quickly as

they had come, going on into the west, but for a long time I could see

the last of the sun shining on them. After night fell I could still see

them in my thoughts and it was because of this that I kept on paddling

when I wanted to lie down and sleep.

More than anything, it was the blue dolphins that took me back home.

Fog came with the night, yet from time to time I

could see the star that stands high in the west, the red star called

Magat which is part of the figure that looks like a crawfish and is

known by that name. The crack in the planks grew wider so I had to stop

often to fill it with fiber and to dip out the water.

The night was very long, longer than the night before. Twice I dozed

kneeling there in the canoe, though I was more afraid than I had ever

been. But the morning broke clear and in front of me lay the dim line of

the island like a great fish sunning itself on the sea.

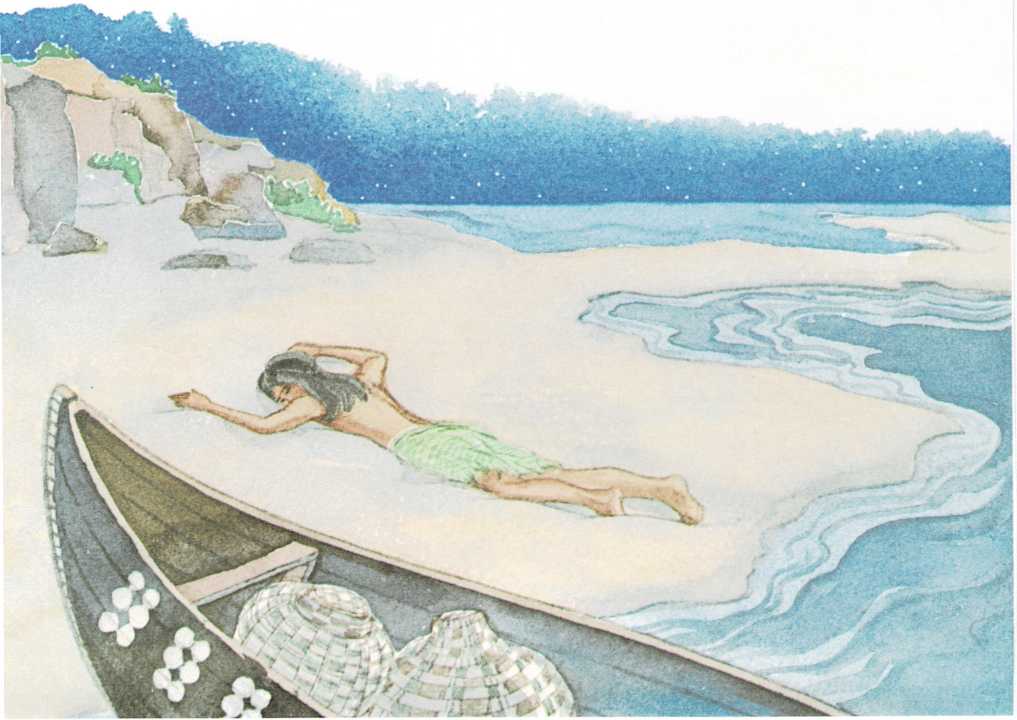

I reached it before the sun was high, the sandspit and its tides that

bore me into the shore. My legs were stiff from kneeling and as the

canoe struck the sand I fell when I rose to climb out. I crawled through

the shallow water and up the beach. There I lay for a long time, hugging

the sand in happiness.

I was too tired to think of the wild dogs. Soon I fell asleep. I was

awakened by the waves dragging at my

feet. Night had come, but being too tired to leave the sandspit, I

crawled to a higher place where I would be safe from the tide, and again

went to sleep.

In the morning I found the canoe a short distance away. I took the

baskets, my spear, and the bow and arrows, and turned the canoe over so

that the tides could not take it out to sea. I then climbed to the

headland where I had lived before.

I felt as if I had been gone a long time as I stood there looking down

from the high rock. I was happy to be home. Everything that I saw—the

otter playing in the kelp, the rings of foam around the rocks that

guarded the harbor, the gulls flying, the tides moving past the

sandspit—filled me with happiness.

I was surprised that I felt this way, for it was only a short time ago

that I had stood on this same rock and felt that I could not bear to

live here another day.

I looked out at the blue water stretching away and all the fear I had

felt during the time of the voyage came back to me. On the morning I

first sighted the island and it had seemed like a great fish sunning

itself, I thought that someday I would make the canoe over and go out

once more to look for the country that lay beyond the ocean. Now I knew

that I would never go again.

The Island of the Blue Dolphins was my home; I had no other.

Will the ship return for Karana? If not, how will a twelve-year-old girl

manage to survive on her own? What will she eat? Where will she find

shelter? And how will she protect herself from the wild dogs? You can

find out by reading the book, Island of the Blue Dolphins. Once you

start it, you won’t be able to put it down. You may also want to try

Call It Courage by Armstrong Sperry, which is about a Polynesian boy

who overcomes his fear of the ocean.