Glooscap and His People

from Glooscap and His Magic: Legends of the Wabanaki Indians by Kay

Hill

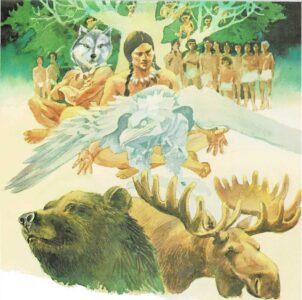

Glooscap is the great culture hero of the Wabanaki (or Abnaki) Indians

of Eastern Canada and the northeastern United States. Here is one of

many legends about this super being.

In the Old Time, long before the White Man came, the Indians believed

that every rock and river, every tree and bird and animal, possessed a

spirit—and some spirits were good and some were evil. Around these

spirits, which they pictured as giants and wizards and magical animals,

the Indians invented marvelous stories called “atookwakuns,” or wonder

tales. They tell these stories to amuse the children, even to this day,

and the stories the children love best are the stories of Glooscap and

his People.

In the beginning, the Indians tell the children, there was just the

forest and the sea—no people and no animals. Then Glooscap came. Where

this wondrous giant was born and when, they cannot tell, but he came

from somewhere in the Sky with Malsum his twin brother to the part of

North America nearest the rising sun. There, anchoring his canoe, he

turned it into a granite island covered with spruce and pine. He called

the island Uktamkoo, the land we know today as Newfoundland. This, in

the beginning, was Glooscap’s lodge.

The Great Chief looked and lived like an ordinary Indian except that he

was twice as tall and twice as strong, and possessed great magic. He was

never sick, never married, never grew old, and never died. He had a

magic belt which gave him great power, and he used this power only for

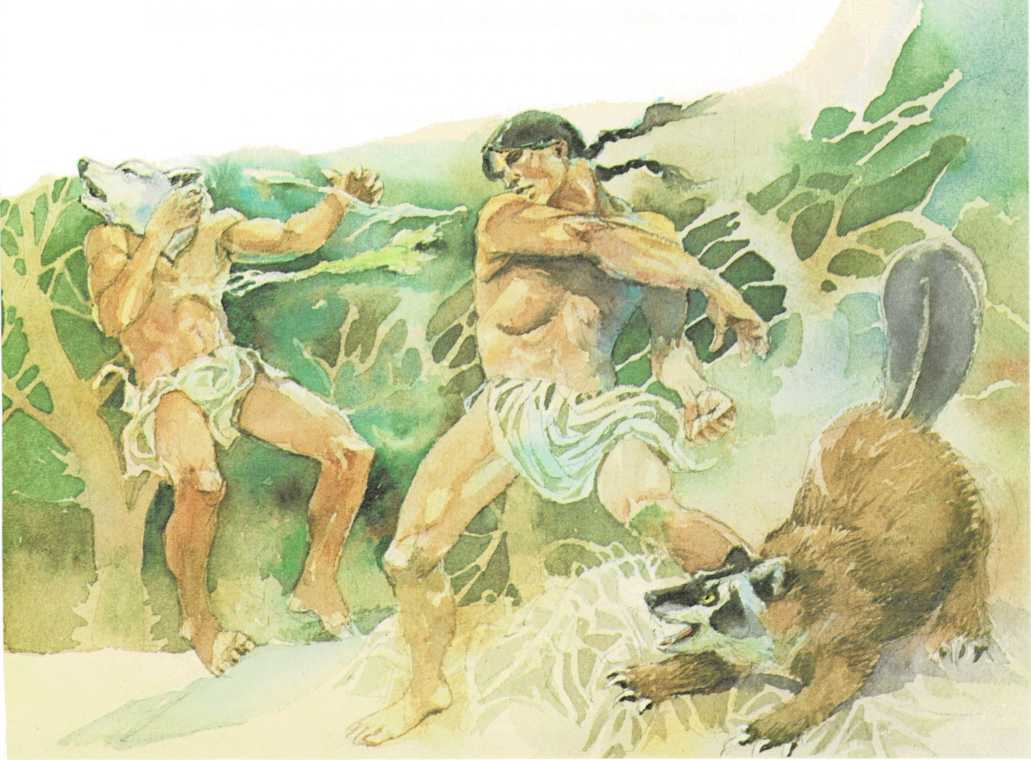

good. Malsum, his brother, also

great of stature, had the head of a wolf and the body of an Indian. He

knew magic too, but he used his power for evil.

It was the warm time when Glooscap came. As he set about his work, the

air was fragrant with balsam and the tang of the sea. First, out of the

rocks, he made the Little People—the fairies, or Megumoowesoos, small

hairy creatures who dwelt among the rocks and made wonderful music on

the flute, such music that all who heard it were bewitched. From amongst

them, Glooscap chose a servant, Marten, who was like a younger brother

to him.

Next Glooscap made men. Taking up his great bow, he shot arrows into the

trunks of ash trees. Out of the trees stepped men and women. They were a

strong and graceful people with light brown skins and shining black

hair, and Glooscap called them the Wabanaki, which means “those who live

where the day breaks.” In time, the Wabanaki left Uktamkoo and divided

into separate tribes and are today a part of the great Algonquin

nation—but in the old days only the Micmacs, Malicetes, Penobscots and

Passamaquoddies, living in the eastern woodlands of Canada and the

United States, were Glooscap’s People.

Gazing upon his handiwork, Glooscap was pleased and his shout of triumph

made the tall pines bend like grass.

He told the people he was their Great Chief and would rule them with

love and justice. He taught them how to build birchbark wigwams and

canoes, how to make weirs for catching fish, and how to identify plants

useful in medicine. He taught them the names of all the Stars, who were

his brothers.

Then, from among them, he chose an elderly woman whom he called

Noogumee, or grandmother, which is a term of respect amongst Indians for

any elderly female. Noogumee was the Great Chief’s housekeeper all her

days.

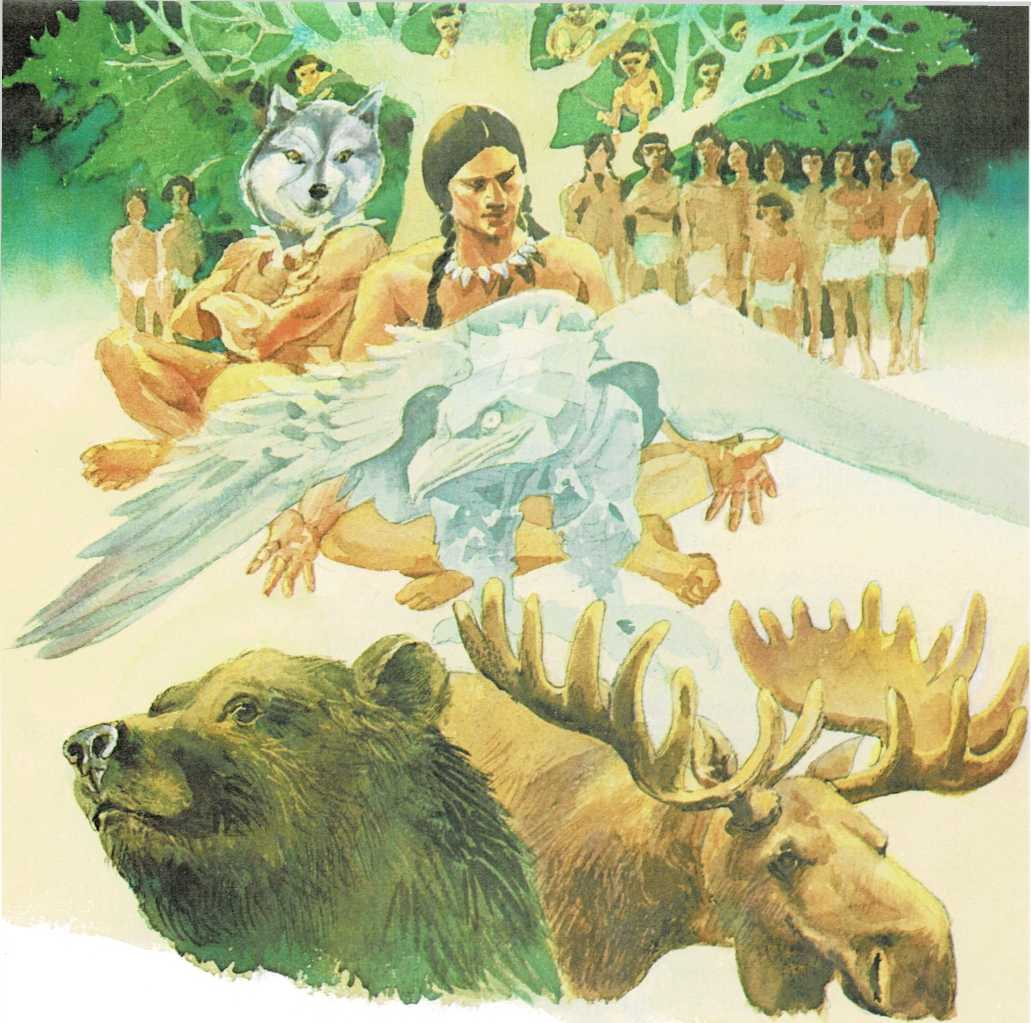

Now, finally, out of rocks and clay, Glooscap made the animals—Miko

the Squirrel, Team the Moose, Mooin the Bear, and many, many others.

Malsum looked on enviously, thinking he too should have had a hand in

creation, but he had not been given that power. However, he whispered an

evil charm, and the remainder of the clay in Glooscap’s hands twisted

and fell to the ground in the form of a strange animal—not beaver, not

badger, not wolverine, but something of all three, and capable of taking

any of these forms he chose.

“His name is Lox!” said Malsum triumphantly.

“So be it,” said Glooscap. “Let Lox live amongst us in peace, so long as

he remains a friend.” Yet he resolved to watch Lox closely, for he could

read the heart and knew that Lox had Malsum’s evil in him.

Now Glooscap had made the animals all very large, most of them larger

and stronger than man. Lox, the troublemaker, at once saw his chance to

make mischief.

He went in his wolverine body to Team the Moose and admired his fine

antlers, which reached up to the top of the tallest pine tree. “If you

should ever meet a man,” said Lox, “you could toss him on your horns up

to the top of the world.”

Now Team, who was just a little bit stupid, went at once to Glooscap and

said, “Please, Master, give me a man, so I can toss him on my horns up

to the top of the world!”

“I should say not!” cried Glooscap, touching Team with his hand—and

the moose was suddenly the size he is today.

Then Lox went in his badger form to the squirrel and said, “With that

magnificent tail of yours, Miko, you could smash down every lodge in the

village.”

“So I could,” said Miko proudly, and with his great tail he swept the

nearest wigwam right off the ground. But the Great Chief was near. He

caught Miko up in his hand and stroked the squirrel’s back until he was

as small as he is today.

“From now on,” said his Master, “you will live in trees and keep your

tail where it belongs.” And since that time Miko the Squirrel has

carried his bushy tail on his back.

Next, the rascally Lox put on his beaver shape and went to Mooin the

Bear, who was hardly any bigger than he is today, but had a much larger

throat.

“Mooin,” said Lox slyly, “supposing you met a man, what would you do to

him?” The bear scratched his head thoughtfully. “Eat him,” he said at

last, with a grin. “Yes, that’s what I’d do—I’d swallow him whole!”

And having said this, Mooin felt his throat begin to shrink.

“From now on,” said Glooscap sternly, “you may swallow only very small

creatures.” And today the bear, big as he is, eats only small animals,

fish and wild berries.

Now the Great Chief was greatly annoyed at the way his animals were

behaving, and wondered if he ought to have made them. He summoned them

all and gave them a solemn warning:

“I have made you man’s equal, but you wish to be his master. Take

care—or he may become yours!”

This did not worry the troublemaker Lox, who only resolved to be more

cunning in the future. He knew very well that Malsum was jealous of

Glooscap and wished to be lord of the Indians himself. He also knew that

both brothers had magic powers and that neither could be killed except

in one certain way. What that way was, each kept secret—from all but

the Stars,

whom they trusted. Each sometimes talked in the starlight to the people

of the Sky.

“Little does Malsum know,” said Glooscap to the Stars, “that I can never

be killed except by the blow of a flowering rush.” And not far off,

Malsum boasted to those same Stars—“I am quite safe from Glooscap’s

power. I can do anything I like, for nothing can harm me but the roots

of a flowering fern.”

Now, alas, Lox was hidden close by and overheard both secrets. Seeing

how he might turn this to his own advantage, he went to Malsum and said

with a knowing smile, “What will you give me, Malsum, if I tell you

Glooscap’s secret?”

“Anything you like,” cried Malsum. “Quick—tell me!” “Nothing can hurt

Glooscap save a flowering rush,”

said the traitor. “Now give me a pair of wings, like the pigeon, so I

can fly.”

But Malsum laughed.

“What need has a beaver of wings?” And kicking the

troublemaker aside, he sped to find a flowering rush.

Lox picked himself up furiously and hurried to Glooscap.

“Master!” he cried, “Malsum knows your secret and

is about to kill you. If you would save yourself, know

that only a fern root can destroy him!”

Glooscap snatched up the nearest fern, root and all, just in

time—for his evil brother was upon him, shouting his war cry. And

all the animals, who were

angry at Glooscap for reducing their size and power, cheered Malsum; but

the Indians were afraid for their Master.

Glooscap braced his feet against a cliff, and Malsum paused. For a

moment, the two crouched face to face, waiting for the moment to strike.

Then the wolf-like Malsum lunged at Glooscap’s head. Twisting his body

aside, the Great Chief flung his weapon. It went swift to its target,

and Malsum leapt back—too late. The fern root pierced his envious

heart, and he died.

Now the Indians rejoiced, and the animals crept sullenly away. Only Lox

came to Glooscap, impudently.

“I’ll have my reward now, Master,” he said, “a pair of wings, like the

pigeon’s.”

“Faithless creature!” Glooscap thundered, knowing full well who had

betrayed him, “I made no such bargain. Begone!” And he hurled stone

after stone at the fleeing Lox. Where the stones fell—in Minas

Basin—they turned into islands and are there still.

And the banished Lox roams the world to this day, appealing to the evil

in men’s hearts and making trouble wherever he goes.

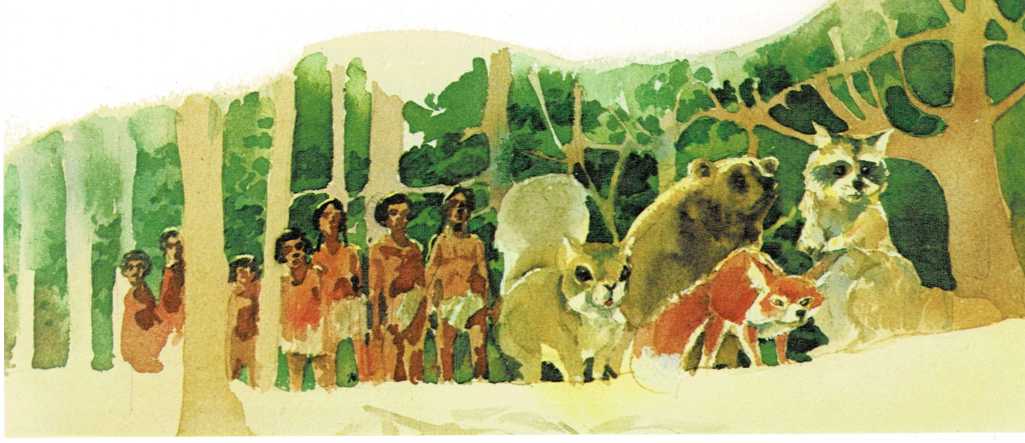

Now Glooscap called his people around him and said, “I made the animals

to be man’s friends, but they have acted with selfishness and treachery.

Hereafter, they shall be your servants and provide you with food and

clothing.”

Then he showed the men how to make bows and arrows and stone-tipped

spears, and how to use them. He also showed the women how to scrape

hides and turn them into clothing.

“Now you have power over even the largest wild creatures,” he said. “Yet

I charge you to use this power gently. If you take more game than you

need for food and clothing, or kill for the pleasure of killing, then

you will be visited by a pitiless giant named Famine, and when he comes

among men, they suffer hunger and die.”

The Indians readily promised to obey Glooscap in this, as in all things.

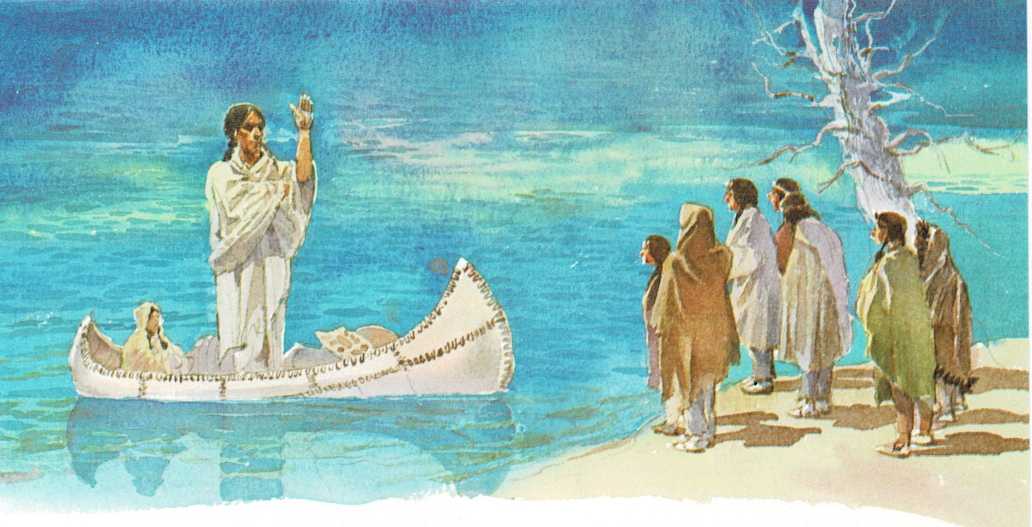

But now, to their dismay, they saw Marten launch the Master’s canoe and

Noogumee entering it with Glooscap’s household goods. Glooscap was

leaving them!

“I must dwell now in a separate place,” said the Great Chief, “so that

you, my people, will learn to stand alone, and become brave and

resourceful. Nevertheless, I shall never be far from you, and whoever

seeks me diligently in time of trouble will find me.”

Then, waving farewell to his sorrowful Wabanaki, Glooscap set off for

the mainland. Rounding the southern tip of what is now Nova Scotia, the

Great Chief paddled up the Bay of Fundy. In the distance, where the Bay

narrows and the great tides of Fundy rush into Minas Basin, Glooscap saw

a long purple headland, like a moose swimming, with clouds for

antlers, and headed his canoe in that direction. Landing, he gazed at

the slope of red sandstone, with its groves of green trees at the

summit, and admired the amethysts encircling its base like a string of

purple beads.

“Here I shall build my lodge,” said Glooscap, and he named the place

Blomidon.

Now Glooscap dwelt on Blomidon a very long time, and during that time

did many wonderful things for his People. Of these things you will hear

in the pages to follow.

But for the present, kespeadooksit, which means “the story ends.”

Glooscap and His Magic by Kay Hill, the book from which this story was

taken, contains many other fine tales about Glooscap. You may also want

to read other Indian legends, such as Skunny Wundy: Seneca Indian

Tales by Arthur C. Parker and Tonweya and the Eagles and. Other Lakota

Indian Tales by Rosebud Yellow Robe.