Stories

Anansi and the Plantains

from Anansi the Spider Man by Philip M. Sherlock

Who was Anansi?

He was a man and he was a spider.

When things went well he was a man, but when he was in great danger he

became a spider, safe in his web high up on the ceiling. That was why

his friend Mouse called him “Ceiling Thomas.”

Anansi’s home was in the villages and forests of West Africa. From there

long years ago thousands of men and women came to the islands of the

Caribbean. They brought with them the stories that they loved, the

stories about clever Br’er Anansi, and his friends Tiger and Crow and

Moos-Moos and Kisander the cat.

Today the people of the islands still tell these stories to each other.

So, in some country village in Jamaica when the sun goes dowm the

children gather round an old woman and listen to the stories of Anansi.

In the dim light they see the animals—Goat, Rat, Crow, and the

others—behaving like men and women. They see how excited everyone

becomes as soon as Anansi appears. They laugh at the way in which he

tricks all the strong animals and gets the better of those who are much

bigger than himself. At last the story comes to an end. The night and

bedtime come. But next day when the children see Ceiling Thomas they

know that he is more than a spider. They know that he is Anansi, the

spider man, and they do him no harm.

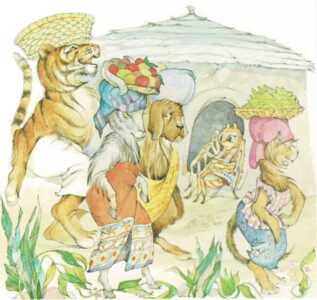

It was market day, but Anansi had no money. He sat at the door of his

cottage and watched Tiger and Kisander the cat, Dog and Goat, and a host

of others hurrying to the market to buy and sell. He had nothing to

sell, for he had not done any work in his field. Turtle had won the few

coins that he had saved in the broken calabash that he kept hidden under

his bed. How was he to find food for his wife Crooky and for the

children? Above all, how was he to find food for himself?

Soon Crooky came to the door and spoke to him.

“You must go out now, Anansi, and find something for us to eat. We have

nothing for lunch, nothing for dinner, and tomorrow is Sunday. What are

we going to do without a scrap of food in the house?”

“I am going out to work for some food,” said Anansi. “Do not worry.

Every day you have seen me go with nothing and come home with something.

You watch and see!”

Anansi walked about until noon and found nothing, so he lay down to

sleep under the shade of a large mango tree. There he slept and waited

until the sun began to go down. Then, in the cool of the evening, he set

off for home. He walked slowly, for he was ashamed to be going home

empty-handed. He was asking himself what he was to do, and where he

would find food for the children, when he came face to face with his old

friend Rat going home with a large bunch of plantains on his head. The

bunch was so big and heavy that Brother Rat had to bend down almost to

the earth to carry it.

Anansi’s eyes shone when he saw the plantains, and he stopped to speak

to his friend Rat.

“How are you, my friend Rat? I haven’t seen you for a very long time.”

“Oh, I am staggering along, staggering along,” said Rat. “And how are

you—and the family?”

Anansi put on his longest face, so long that his chin almost touched his

toes. He groaned and shook his head. “Ah, Brother Rat,” he said, “times

are hard, times are very hard. I can hardly find a thing to eat from one

day to the next.” At this tears came into his eyes, and he went on:

“I walked all yesterday. I have been walking all today and I haven’t

found a yam or a plantain.” He glanced for a moment at the large bunch

of plantains. “Ah, Br’er Rat, the children will have nothing but water

for supper tonight.”

“I am sorry to hear that,” said Rat, “very sorry indeed. I know how I

would feel if I had to go home to my wife and children without any

food.”

“Without even a plantain,” said Anansi, and again he looked for a moment

at the plantains.

Br’er Rat looked at the bunch of plantains, too. He put it on the ground

and looked at it in silence.

Anansi said nothing, but he moved toward the plantains. They drew him

like a magnet. He could not take his eyes away from them, except for an

occasional quick glance at Rat’s face. Rat said nothing. Anansi said

nothing. They both looked at the plantains.

Then at last Anansi spoke. “My friend,” he said, “what a lovely bunch of

plantains! Where did you get it in these hard times?”

“It’s all that I had left in my field, Anansi. This bunch must last

until the peas are ready, and they are not ready yet.”

“But they will be ready soon,” said Anansi, “they will be ready soon.

Brother Rat, give me one or two of the plantains. The children have

eaten nothing, and they have only water for supper.”

“All right, Anansi,” said Rat. “Just wait a minute.”

Rat counted all the plantains carefully and then said, “Well, perhaps,

Br’er Anansi, perhaps!” Then he counted them again and finally broke off

the four smallest plantains and gave them to Anansi.

“Thank you,” said Anansi, “thank you, my good friend. But, Rat, it’s

four plantains, and there are five of us in the family—my wife, the

three children, and myself.”

Rat took no notice of this. He only said, “Help me to put this bunch of

plantains on my head, Br’er Anansi, and do not try to break off any

more.”

So Anansi had to help Rat to put the bunch of plantains back on his

head. Rat went off, walking slowly because of the weight of the bunch.

Then Anansi set off for his home. He could walk quickly because the four

plantains were not a heavy burden. When he got to his home he handed the

four plantains to Crooky, his wife, and told her to roast them. He went

outside and sat down in the shade of the mango tree until Crooky called

out to say that the plantains were ready.

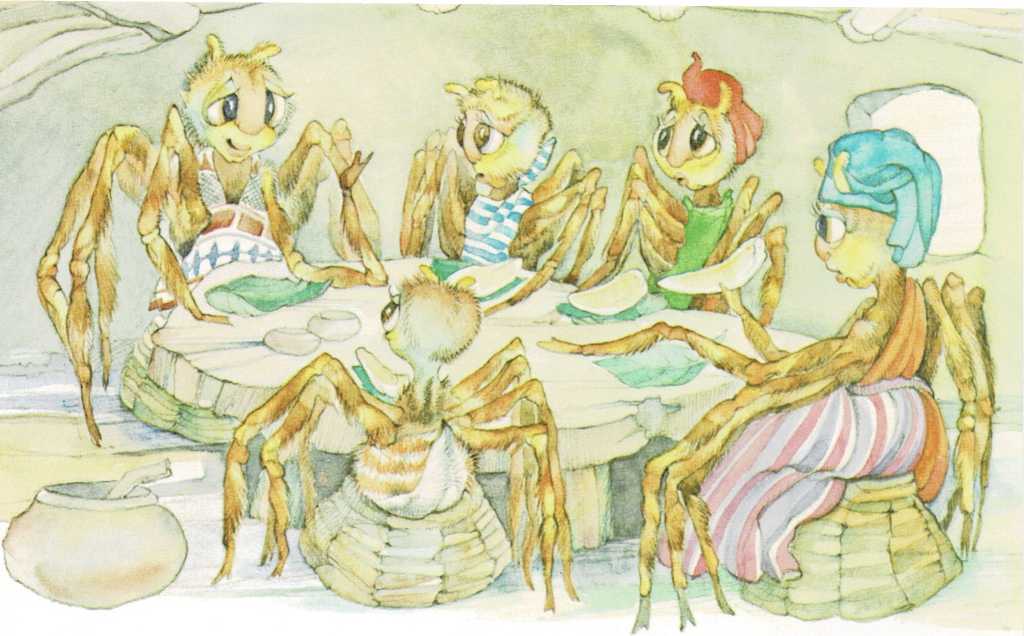

Anansi went back inside. There were the four plantains, nicely roasted.

He took up one and gave it to the girl. He gave one each to the two

boys. He gave the last and biggest plantain to his wife. After that he

sat down empty-handed and very very sad-looking, and his wife said to

him, “Don’t you want some of the plantains?”

“No,” said Anansi, with a deep sigh. “There are only enough for four of

us. I’m hungry, too, because I haven’t had anything to eat; but there

are just enough for you.”

The little child asked, “Aren’t you hungry, Papa?” “Yes, my child, I am

hungry, but you are too little.

You cannot find food for yourselves. It’s better for me to remain hungry

as long as your stomachs are filled.” “No, Papa,” shouted the children,

“you must have half of my plantain.” They all broke their plantains in

two, and each one gave Anansi a half. When Crooky saw what was happening

she gave Anansi half of her plantain, too. So, in the end, Anansi got

more than anyone, just as usual.

dk

There are other wonderful Anansi stories in Anansi the Spider Man by

Philip M. Sherlock, the book from which this tale came. And you might

try Ears and Tails and Common Sense: More Stories from the Caribbean

by Philip M. Sherlock and Hilary Sherlock. Or, for the West African

versions, try Ananse the Spider: Tales from an Ashanti Village and

Tales of an Ashanti Father, both by Peggy Appiah.