Stories

A Stranger in the Land

from The Witch of Blackbird Pond by Elizabeth George Speare

All her life, Kit Tyler has lived with her wealthy grandfather on the

warm, sunny island of Barbados in the West Indies. When her grandfather

dies, the only family left is an aunt in Wethersfield, Connecticut.

Hoping to live with her aunt, sixteen-year-old Kit takes passage on a

ship bound for Connecticut. For days now, the Dolphin has been working

its way slowly up the Connecticut River toward Wethersfield. It is the

year 1687, and to Kit the land seems as bleak and forbidding as the

people she has met.

Early the next morning a contrary breeze came whistling along the river.

The Dolphin sprang to life, scudded the last few miles, and bumped

against the wharf at Wethersfield landing. The shore, muffled in thick

scarves of drifting mist, looked scarcely different from the miles of

unbroken forest that they had seen for the past week.

Sailors began vigorously to roll out the great casks of molasses and

pile them along the wharf. Two of the men lowered over the side the

seven small leather trunks that held all of Kit’s belongings and piled

them, one beside the other, on the wet planking. Kit clambered down the

ladder and stood for the second time on the alien shore that was to be

her home.

Her heart sank. This was Wethersfield! Just a narrow sandy stretch of shoreline, a few piles sunk in the river with rough planking for a platform. Out of the mist jutted a row of cavernous wooden structures that must be warehouses, and beyond that the dense,

dripping green of fields and woods. No town, not a house, only a few men

and boys and two yapping dogs who had come to meet the boat. With

something like panic Kit watched Goodwife Cruff descend the ladder and

stride ahead of her husband along the wharf. Prudence, dragging at her

mother’s hand, gazed back imploringly as they passed.

“Ma,” she ventured timidly, “the pretty lady got off here at

Wethersfield!”

Kit summoned the boldness to speak to her. “Yes,

Prudence,” she called clearly. “And I hope that I will see you often.”

Goodwife Gruff halted and glared at Kit. “I’ll thank you to let my child

alone!” she spat out. “We do not welcome strangers in this town, and you

be the kind we like least.” Jerking Prudence nearly off her feet, she

marched firmly up the dirt road and disappeared in the fog.

Even John Holbrook’s farewells were abstracted. A formal bow, a polite

wish for her pleasant arrival, and he, too, strode eagerly into the fog

in quest of his new teacher. Then Kit saw Captain Eaton approaching and

knew that the moment had come when the truth would have to be told.

“There must be some mistake,” the captain began. “We signaled yesterday

that we would reach Wethersfield at dawn. I expected that your aunt and

uncle would be here to meet you no matter how early it might be.”

Kit swallowed and gathered her courage. “Captain Eaton,” she said

boldly, “my uncle and aunt can hardly be blamed for not meeting me. You

see—well, to be honest, they do not even know that I am coming.”

The captain’s jaw tightened. “You gave me to understand that they had

sent for you to come.”

Kit lifted her head proudly. “I told you that they wanted me,” she

corrected him. “Mistress Wood is my mother’s sister. Naturally she would

always want me to come.”

“Even assuming that to be true, how could you be sure they were still in

Connecticut?”

“My Aunt Rachel’s last letter came only six months ago.”

He scowled with annoyance. “You know very well that I should never have

taken you on board had I known this. Now I shall have to take the time

to find where your uncle lives and deliver you. But understand, I take

no responsibility for your coming.”

Kit’s head went higher. “I am entirely responsible for my own coming,”

she assured him haughtily.

“Fair enough,” the captain responded grimly. “Look here, Nat,” he turned

back. “See if two hands can be spared to carry this baggage.”

Kit’s cheeks went scarlet. Why should Nat, who had carefully been

somewhere else during the whole of the last nine days, have to be so

handy at just this moment? Now whatever befell he was going to be there

to witness it, with those mocking blue eyes and that maddening cool

amusement. What if Aunt Rachel—but there was no time for doubt now.

Between trying to hold up her head confidently and at the same time find

a place to set down her dainty kid shoes between the slimy ruts and the

mud puddles, Kit had all she could tend to.

Along with her pretty shoes, Kit’s spirits sank lower at each step. She

had clutched at a hope that the dark fringe of dripping trees might

somehow be concealing the town she had anticipated. But as they plodded

along the dirt road past wide stumpy fields, her last hopes died. There

was no fine town of Wethersfield. There was a mere settlement, far more

lonely and dreary than Saybrook.

A man in a leather coat and breeches led a cow along the road. He

stopped to stare at them, and even the cow looked astonished. Captain

Eaton took advantage of the meeting to ask directions.

“High Street,” the man said, pointing his jagged stick. “Matthew Wood’s

place is the third house beyond the Common.”

High Street indeed! No more than a cow path! Kit’s shoes were wet

through, and the soaked ruffles of her gown slapped against her ankles.

She would naturally have lifted her skirts free of the uncut grass, but

a new self-consciousness restrained her. She was aware at every step of

the young man who strode behind her with a trunk balanced easily on each

shoulder.

She relaxed slightly at the first glimpse of her uncle’s house. At least

it looked solid and respectable, compared to the cabins they had passed.

Two and a half stories it stood, gracefully proportioned, with leaded

glass windows and clapboards weathered to a silvery gray.

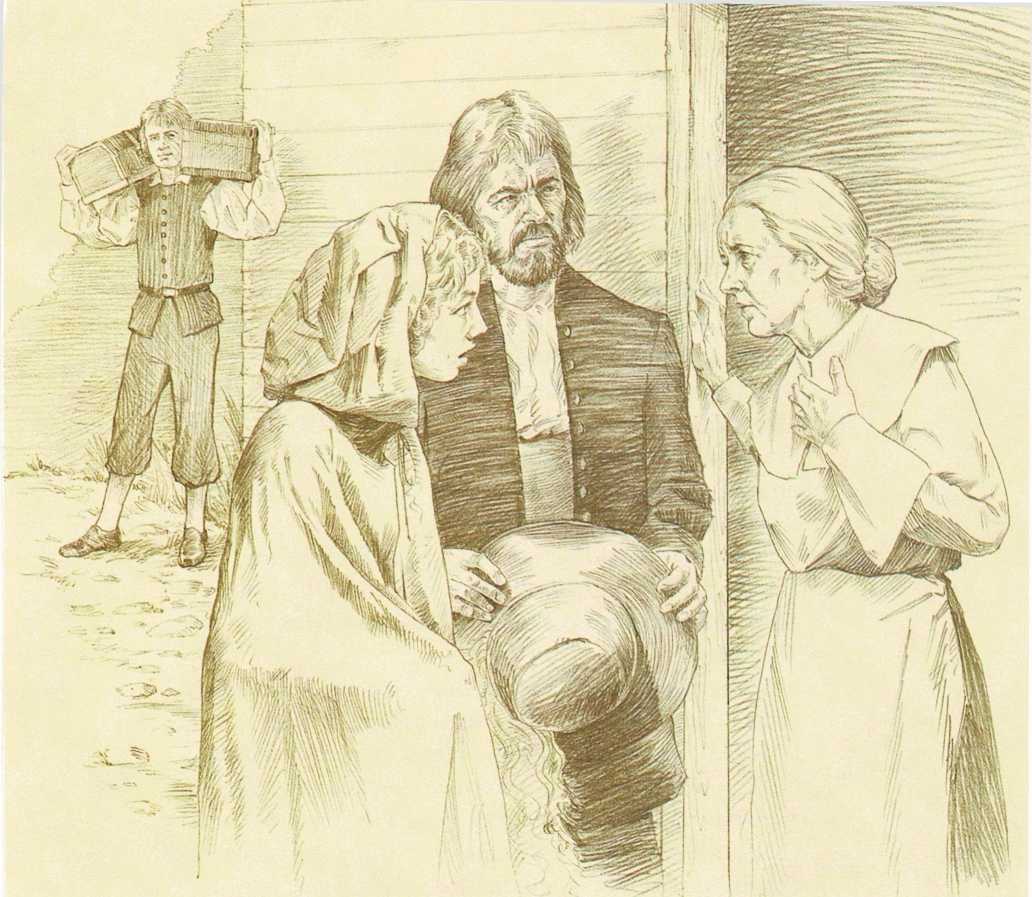

The captain lifted the iron knocker and let it fall with a thud that

echoed in the pit of the girl’s stomach. For a moment she could not

breathe at all. Then the door opened and a thin, gray-haired woman stood

on the threshold. She was quite plainly a servant, and Kit was impatient

when the captain removed his hat and spoke with courtesy.

“Do I have the honor of addressing—?”

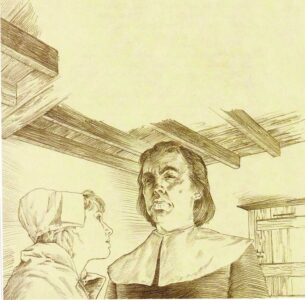

The woman did not even hear him. Her look had flashed past to the girl

who stood just behind, and her face had suddenly gone white. One hand

reached to clutch the doorpost.

“Margaret!” The word was no more than a whisper. For a moment the two

women stared at each other. Then realization swept over Kit.

“No, Aunt Rachel!” she cried. “Don’t look like that!

It is Kit! I am Margaret’s daughter.”

“Kit? You mean—can it possibly be Katherine Tyler? For a moment I

thought—oh, my dear child, how wonderful!”

All at once such a warmth and happiness swept over her pale face that

Kit too was startled. Yes, this strange woman was indeed Aunt Rachel,

and once, a long time ago, she must have been very beautiful.

Captain Eaton cleared his throat. “Well,” he observed, “I am relieved

that this has turned out well after all. What will you have me do with

the baggage, ma’am?”

Rachel Wood’s eyes focused for the first time on the three trunk

bearers. “Goodness,” she gasped, “do all these belong to you, child? You

can just set them there,

I suppose, and I’ll ask my husband about them. Can I offer you and your

men some breakfast, sir?”

“Thank you, we can’t spare any more time. Good day, young lady. I’ll

tell my wife I saw you safely here.”

“I’m sorry to have caused you trouble,” Kit said sincerely. “And I do

thank you, all of you.”

Two of the three sailors had already started back along the road, but

Nat still stood beside the trunks and looked down at her. As their eyes

met, something flashed between them, a question that was suddenly

weighted with regret. But the instant was gone before she could grasp

it, and the mocking light has sprung again into his eyes.

“Remember,” he said softly. “Only the guilty ones stay afloat.”[^8] And

then he was gone.

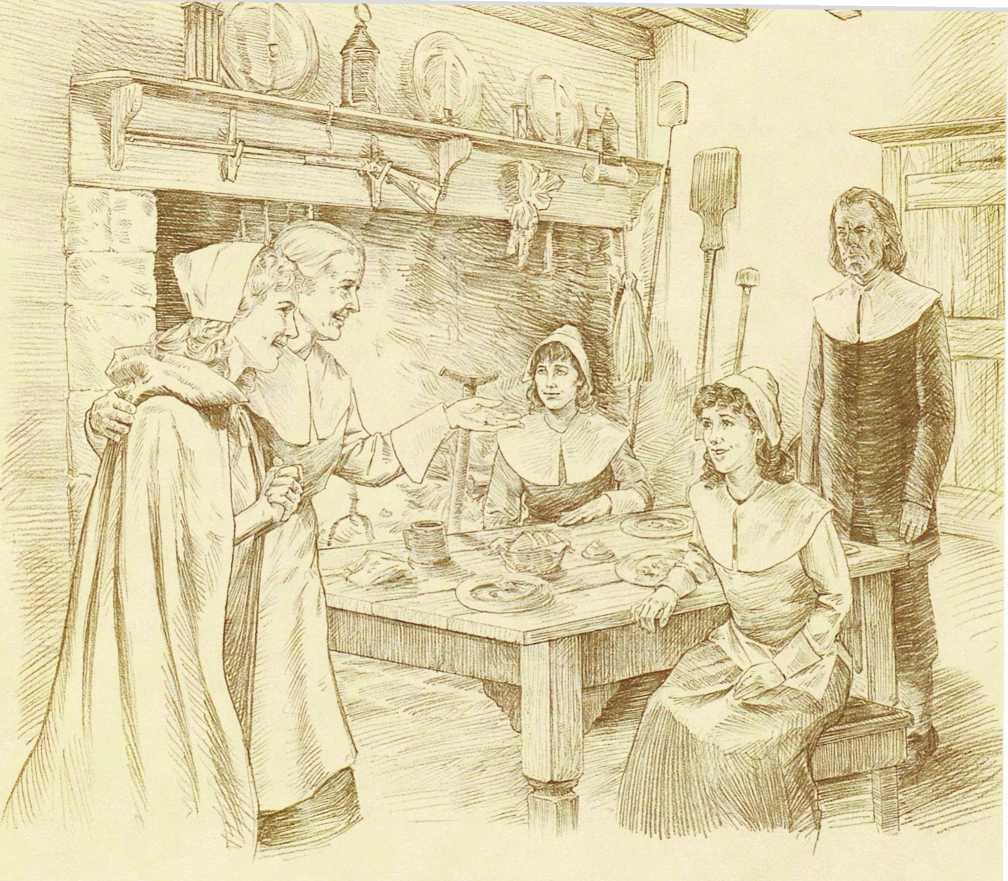

The doorway of Matthew Wood’s house led into a shallow hallway from

which a narrow flight of stairs climbed steeply. Through a second door

Kit stepped into the welcome of the great kitchen. In a fireplace that

filled half one side of the room a bright fire crackled, throwing

glancing patterns of light on creamy plaster walls. There was a gleam of

rubbed wood and burnished pewter.

“Matthew! Girls!” cried her aunt. “Something wonderful has happened!

Here is Katherine Tyler, my sister Margaret’s girl, come all the way

from Barbados!”

Three people stared up at her from the plain board table. Then, from his

place at the head, a man unfolded his tall angular body and came toward

her.

“You are welcome, Katherine,” he said gravely, and took her hand in his

bony fingers. She could not read the faintest sign of welcome in his

thin stern lips or in the dark eyes that glowered fiercely at her from

under heavy grizzled eyebrows.

Behind him a girl sprang up from the table and came forward. “This is

your cousin Judith,” her aunt said, and Kit gasped with pleasure.

Judith’s face fulfilled in every exquisite detail the picture she had

treasured of her imagined aunt. The clear white skin, the blue eyes

under the dark fringe of lashes, the black hair that curled against her

shoulders, and the haughty lift of her perfect small chin—this girl

could have been the toast of a regiment!

“And your other cousin, Mercy.” The second girl had risen more slowly,

and at first Kit was only aware of the most extraordinary eyes she had

ever seen, gray as rain at sea, wide and clear and filled with light.

Then, as Mercy stepped forward, one shoulder dipped and jerked back

grotesquely, and Kit realized that she leaned on crutches.

“How lovely,” breathed Mercy, her voice as arresting as her eyes, “to

see you after all these years, Katherine!”

“Will you call me Kit?” The question sounded abrupt. Kit had been her

grandfather’s name for her, and something in Mercy’s smile had reached

straight across the gulf so that suddenly she wanted to hear the name

spoken again.

“Have you had breakfast?”

“I guess not. I hadn’t even thought of it.”

“Then ’tis lucky we are eating late this morning,” said her aunt. “Take

her cloak, Judith. Come close to the fire, my dear, your skirt is

soaking.”

As Kit threw back the woolen cloak, Judith’s reaching hand fell back.

“My goodness!” she exclaimed. “You wore a dress like that to travel

in?”

In her eagerness to make a good impression Kit had selected this dress

with care, but here in this plain room it seemed overelegant. The three

other women were all wearing some nondescript sort of coarse gray stuff.

Judith laid the cloak thoughtfully on a bench and reached to touch Kit’s

glove.

“What beautiful embroidery,” she said admiringly.

“Do you like them? I’ll give you some just like them if you like. I have

several pairs in my trunk.”

Judith’s eyes narrowed. Rachel Wood was setting out a pewter mug and

spoon and a crude wooden plate.

“Sit here, Katherine, where the fire will warm your back. Tell us how

you happened to come so far. Did your grandfather come with you?”

“My grandfather died four months ago,” Kit explained.

“Why, you poor child! All alone there on that island! Who did come with

you, then?”

“I came alone.”

“Praise be!” her aunt marveled. “Well, you’re here safe and sound. Have

some corn bread, my dear. ‘Twas baked fresh yesterday, and there is new

butter.”

Surprisingly, the bread tasted delicious, though of a coarse texture

like nothing she had ever tasted before. Kit lifted the pewter mug

thirstily, and abruptly set it down. “Is that water?” she asked

politely.

“Of course, drawn fresh from the spring this morning.”

Water! For breakfast! But the corn bread was good, and she managed a

second piece in spite of her dry tongue.

Rachel Wood could not seem to look away from the young face across the

table, and every few moments her eyes brimmed over with tears.

“I declare, you look so like her it takes my breath away. But all the

same, there is a hint of your father there, too. I can see it if I look

closely.”

“You remember my father?” Kit asked eagerly.

“I remember him well. A fine upstanding lad he was, and I never could

blame Margaret. But it broke my heart to have her go so far.”

But Rachel had come even farther. What could she have seen in that

fierce silent man to draw her away from England? Could he have been

handsome? Perhaps, with that strong regal nose and high forehead. But so

terrifying!

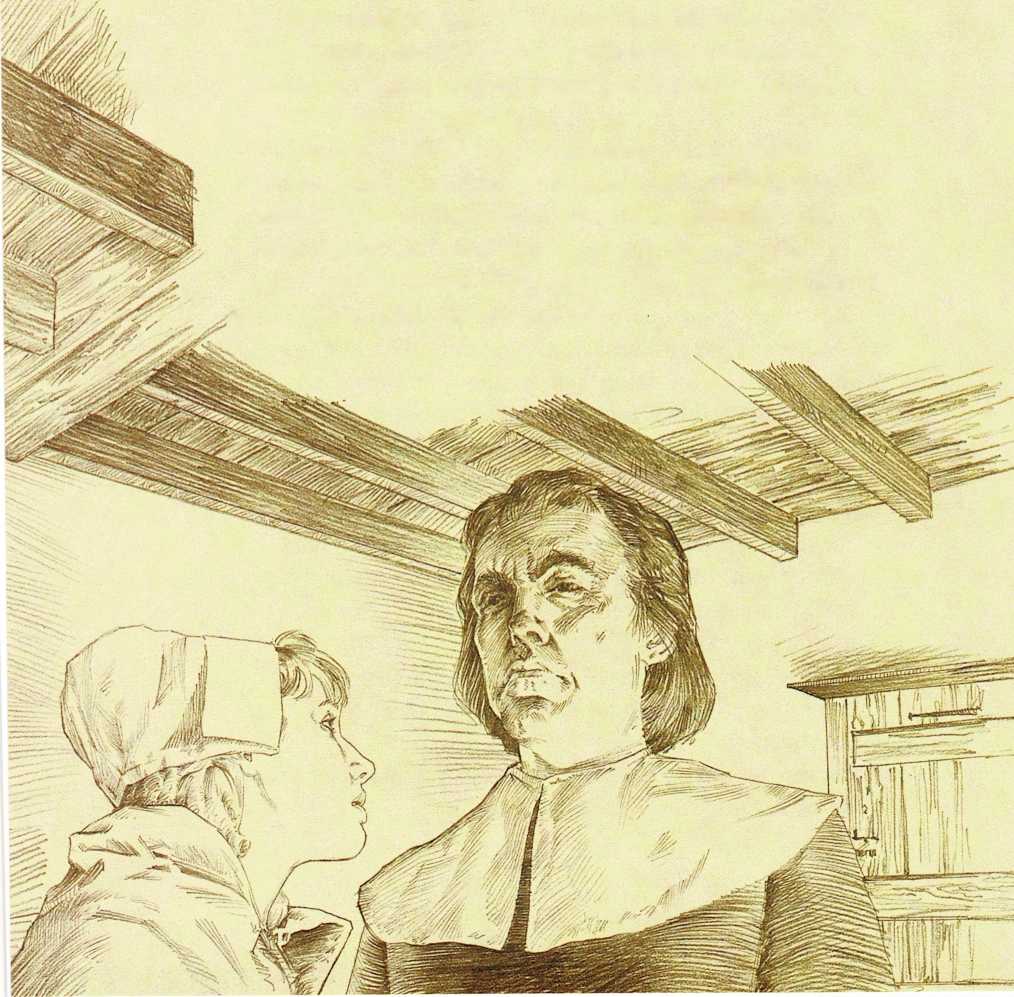

Matthew Wood had not sat down at the table with the others. Though he

had said nothing, Kit had been aware that not a motion had escaped his

intent scowl. Now he pulled down a leather jacket from a peg on the wall

and thrust his long arms into the sleeves.

“I will be working in the south meadow,” he told his wife. “You had best

not expect me till sundown.”

At the open door, however, he stopped and looked back at them. “What is

all this?” he inquired coldly.

“Oh,” said Kit, scrambling to her feet. “I forgot.

Those are my trunks.”

“Yours? Seven trunks? What can be in them?”

“Why—my clothes, and a few things of Grandfather’s.”

“Seven trunks of clothes, all the way from Barbados just for a visit?”

The cold measured word fell like so many stones into the quiet room.

Kit’s throat was so dry she longed now to swallow the water. She lifted

her chin and looked directly into those searching eyes.

“I have not come for a visit, sir.” she answered. “I have come to stay

with you.”

There was a little gasp from Rachel. Matthew Wood closed the door

deliberately and came back toward the table. “Why did you not write to

us first?”

All her life, whenever her grandfather had asked her

a question he had expected a direct answer. Now, in

this stern man facing her, so totally different from her grandfather,

Kit sensed the same quality of directness, and out of an instinctive

respect she gave the only honest answer she could.“I did not dare to write,” she said. “I was afraid

that you might not tell me to come, and I had to come.” Rachel leaned

forward to put a hand on Kit’s arm. “We would not have refused you if

you were inneed,” said her uncle. “But a step like this should not be taken

without due pondering.”

“Matthew,” protested Rachel timidly, “what is there to ponder? We are

the only family she has. Let us talk about it later. Now Katherine is

tired, and your work has been delayed already.”

Matthew Wood drew up a chair and sat down heavily. “The work will have

to wait,” he said. “It is best that we understand this matter at once.

How did you come to set sail all alone?”

“There was a ship in the harbor and they said it was from Connecticut. I

should have sent a letter, I know, but it might have been months before

another ship came. So instead of writing I decided to come myself.”

“You mean that, just on an impulse, you left your rightful home and

sailed halfway across the world?”

“No, it was not an impulse exactly. You see, I really had no home to

leave.”

“What of your grandfather’s estate? I always understood he was a wealthy

man.”

“I suppose he was wealthy, once. But he had not been well for a long

time. I think for years he was not able to manage the plantation, but no

one realized it. He left everything more and more to the overseer, a man

named Bryant. Last winter Bryant sold off the whole crop and then

disappeared. Probably he sailed back to England on the trading ship.

Grandfather couldn’t believe it. After that he was never really well.

The other plantation owners were his friends. Nobody ever pressed him,

but after he died there just seemed to be debts everywhere, wherever I

turned.”

“Did you pay them?”

“Yes, every one of them. All the land had to be sold, and the house and

the slaves, and all the furniture from England. There wasn’t anything

left, not even enough for my passage. To pay my way on the ship I had to

sell my own Negro girl.”

“Humph!” With one syllable Matthew disposed of the sacrifice, only a

little less sharp than Grandfather’s loss, of the little African slave

who had been her shadow for twelve years. There was an awkward silence.

Kit found Mercy’s eyes and was steadied by the quiet sympathy she saw

there. Then her aunt came to put an arm across her shoulder.

“Poor Katherine! It must have been terrible for you! You were perfectly

right to come to us. You do believe she was right, don’t you Matthew?”

“Yes,” her husband conceded harshly. “She was right, I suppose, since we

are her only kin. I will bring in the baggage.” At the door he turned

again. “Your grandfather was a King’s man, I reckon?”

“He was a Royalist, sir. Here in America are you not also subjects of

King James?”

Without answering, Matthew Wood left the room. Seven times he returned,

bending his tall frame to enter the doorway, and with wordless

disapproval set down one after the other the seven small trunks. They

filled one entire end of the room.

“Where on earth can we put them?” quavered her aunt. “I will find a

place for them later in the attic,” said her husband. “Seven trunks! The

whole town will be talking about it before nightfall.”

If you enjoyed this part of The Witch of Blackbird Pond, you will want

to read the rest of the book. As you might expect, high-spirited Kit

rebels against many of the Puritan ways of life, especially the

persecution of so-called witches. And this leads to Kit herself being

accused of witchcraft and brought to trial. You might also try another

of Mrs. Speare’s books, Calico Captive, an exciting tale, based on

actual events, of a girl captured by Indians.