Stories

A New Way

from Toolmaker by Jill Paton Walsh

This story takes place many thousands of years ago, in the time called

the Stone Age, when people made and used stone tools. Ra is a fine

toolmaker, and his skill leads to a new way of life.

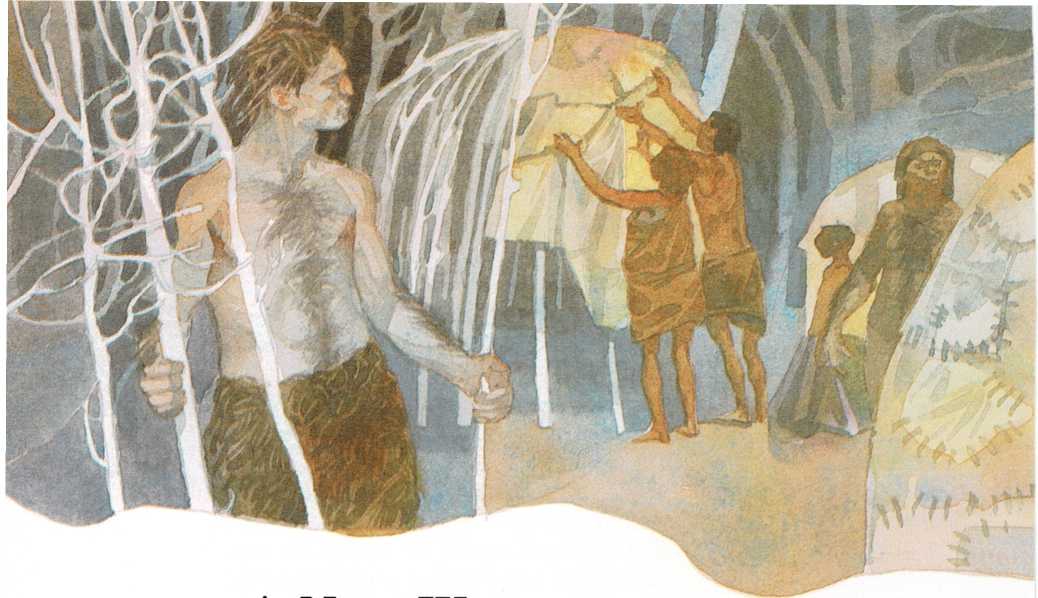

On the grassy slopes in the shelter of the wood, and just a little above

the stream, Ra’s tribe were busy making shelters for the summer, each

family building one hut. They dug away the earth of the hillside till

they got down to a solid, firm floor; then they made a framework of

branches, and stretched over it tents made of skins. There were many

skins in a tent, all carefully stitched together with overlapping edges

to keep out the wind and rain. Ra had not earned one yet—his hut would

be covered in bracken and brushwood. He looked enviously at the others.

Nearly all the huts were almost finished, but only the

Great-grandmother’s was completely ready, for everyone had to help with

hers before starting their own. Ra’s house was slowest of all because he

had nobody helping him. Among the forest tribes a boy lived with his

mother’s and grandmother’s family; but Ra’s mother had died in the snows

of the winter which was just passing, and he had not yet gathered enough

skins and bones and flint tools to buy himself a wife, and join her

family. So for the time being he was alone, and had to live in a hut by

himself.

He had scraped an earth floor out of the grassy slope. Now he was making

a ring of pliable sticks set upright in the ground all around it. He set

to work with the new bundle. First he made a hole by driving a piece of

bone into the ground with a large stone for a hammer. Then he rocked the

bone drill to and fro, pulled it out of the ground, and set the hazel

branch in the hole, wedging it firmly with a little loose earth. Soon

the ring of sticks was finished, with a gap in it for a door. Ra unwound

from his waist a long strip of leather, and reaching up he bent the

hazel branches down over his head one by one, and tied them into a

bundle with his thong.

It was getting dark now, and Ra went hastily down to the stream to find

a piece of flint in the pebbles in the water, to make himself a new axe.

There was no time now to gather bracken to cover the framework of his

hut—that would have to wait till tomorrow. He found a big heavy stone

of the right sort, and then went to one of the bright fires which now

blazed on the slope.

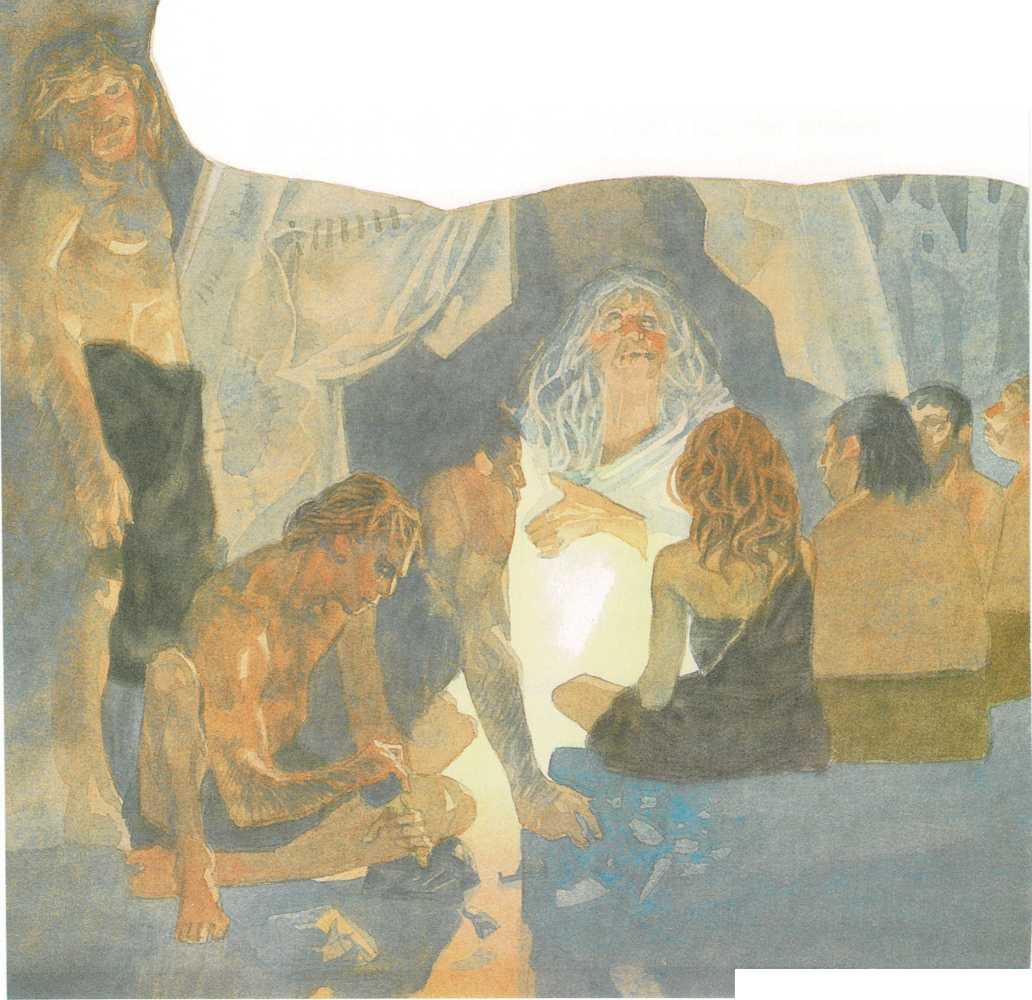

He bowed to the grandmother of the family, who sat between the fire and

the door-hole of the hut, in the place of honour.

“Is there room beside your fire, mother?” he asked her.

“Sit Ra, there is room,” she said. Ra sat down a

little way outside the family circle, and began to make his new axe,

working in the firelight where it fell between the shadows of Brun and

Mi, a boy and girl only a little older than Ra. First Ra broke his stone

in two against the ground. Then he chose the better half, and wedged it

firmly against his bent knee on the ground. Then he took from his

leather pouch a short piece of the leg bone of a stag, and placing one

end against the axe stone, first here, and then there, he struck the

other end with the rejected half of the stone, making flakes of flint

fly off in all directions.

Ra was good at making axes, but the light was poor, and he bent closely

over his work. Even so he could feel that someone was watching him. Ra

glanced up,

hoping it was Mi, and his eyes met those of Yul. Yul was a grown man,

tall and strong, some said the best hunter in the tribe. And he had

hunted with Ra’s father long ago. Ra was in awe of him; he looked away

quickly. When he had finished his axe he stood up to go.

“May the hunt be good tomorrow to those who shared fire with me

tonight,” he said.

In his own unfinished house he lay down to sleep. There was nothing else

to do, for the day had gone in travelling, and in hut making, there had

been no time to hunt, and so there was nothing to eat. Ra was used to

going to bed with an empty stomach, but all winter he had slept in a

deep cave in the distant hills, and he was not used to sleeping in the

open. The year had only just begun to turn warmer, and the leaves were

scarcely breaking bud on the trees when the Great-grandmother had moved

them out of the caves. It was still sharply cold, and a wind swept the

sloping glade. Shivering, Ra wished he had finished his house. Through

the web of sticks over his head he could see the cold stars—the

distant camp fires of the spirit folk who hunt the moon.

“May their arrows stray, their spear-shafts break, their traps all fail

to spring!” muttered Ra to himself, for the moon was useful to his

tribe. Not only the stars disturbed him; unseen creatures moved in the

forest and in the grasses all night long. The echoing tapping of

dripping water in the cave had gone, and instead there were the quiet

movements of living things going about their business, and hunting each

other in the dark. And although he slept, Ra slept so lightly all night

long that he dimly knew from the sound and smell of them what creatures

had come near. No wolf or wildcat came to startle him awake, but he

drowsed on the chill earth till the dawn.

When he woke he went to the stream, and drank

greedily, lifting the water to his mouth in cupped hands. Cold trickles

ran down his forearms, sleeking the thick hair that had grown upon them

last summer. And when he returned to his hut he had a visitor. Yul stood

there.

“Is there room beside your fire, Ra?” he asked. “There is no fire yet,

but there is room,” said Ra. Yul sat down. “Show me the axe you made at

our fireside last night,” he said. Ra stared at Yul in surprise. Then he

picked up the axe, and held it out to Yul. Yul took it, and turned it

over and over in his hands. Then he held it with the thick end in his

palm, and tried it, striking it against the ground.

“This is a good axe, Ra,” he said.

“It is mine,” said Ra, puzzled by all this talk of his axe. “I made it.”

“You were quick and deft about making it,” said Yul. “I take longer. And

when I have an axe to make,

I gather several stones, so that I need not stop to look for another

when the one I am working splits in the wrong place. You had only one

stone with you.”

“The stones are good to me, Yul. They almost always break as I wish them

to.”

“Since that is so, Ra, will you make a new spearhead for me? Hard though

I try, I cannot make them balance so that the spear flies really

straight. You make me a good one.”

Ra was silent. This was a new thing Yul was doing; new things frightened

Ra. The men of his tribe each did everything for himself. There were no

rules for this sort of asking.

“I must hunt, Yul,” he said at last. “I am hungry.”

“Today I will bring you food. I will hunt until I have enough for two,

and share what I catch with you. You can sit here and make me the spear

which I need. Do this for me, Ra.”

“I will do it,” said Ra, unhappily. Indeed one had no choice but to do

what Yul wanted; he was big and strong. He could have knocked Ra down

with one hand only. Ra did not dare refuse him.

So that morning Ra stood at his door like a woman, watching the men and

dogs go out to hunt. The dogs ran yelping at the hunters’ heels, and the

men walked away into the forest, carrying spears, and bows, and bundles

of arrows. The barking sounded clearly in the cold morning, and echoed

faintly from the bare hill above the wooded valley. The sounds came more

and more distant to Ra’s ears. The quiet of the camp made him uneasy. He

wanted to run after the hunt, but instead he went looking for a good

piece of flint.

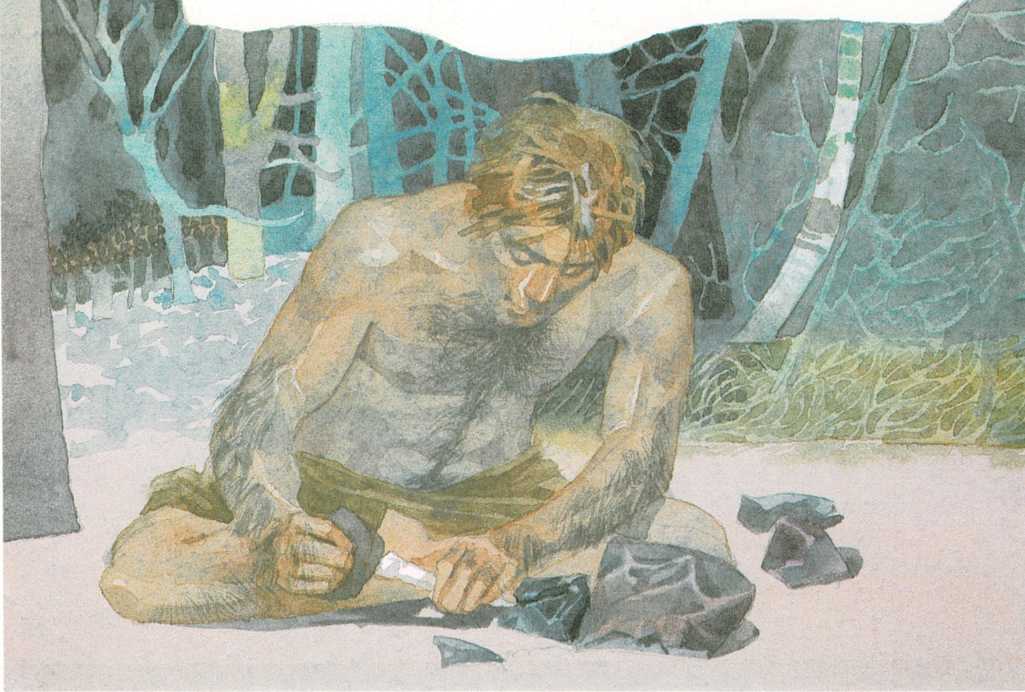

He returned to his hut a while later with two large lumps of flint

tucked under each arm. Then he sat down and set to work. First he wedged

one of his stones firmly on the ground with a little earth, to make an

anvil. Then he chose the best of the stones,

and taking it in two hands raised it above his head, and brought it hard

down on the anvil stone so that it broke cleanly in two across the

middle. He took the larger half, and set it down with the new broken

surface upwards. And now he took his bone chisel and a spare piece of

stone to bang it with. He had to get the slant of the chisel exactly

right to make the flint split where he wanted it to. First he struck the

stone round the rim of the new surface; and at each blow a flake of

stone cracked off the side, so that soon all the hard rough surface of

the stone had been struck away, and he was left with a block of pure

black, unweathered flint.

Now he worked more carefully still. He struck the top surface of his

block near the edge, so that a long narrow flake of flint broke off the

side. This flake would make a good knife; Ra put it on one side. Then he

tried again, and this time got a shorter, wider chip. Just what he

wanted. He put the block aside and

started to work on the chip. It was wafer thin at the edges, and thick

in the middle. Ra tapped the edges gently, and broke off little pieces

until he had rounded it into a leaf shape. Then he trimmed it, holding a

stick at a slant on his anvil, laying the edge of the spearhead against

the stick, and pressing the stick upwards under the thin edge of the

stone blade until a little flake dropped off. These tiny flakes left a

beautiful rippled surface on the flint, like a light wind on dark water.

They also left a wavy, bitter-sharp edge. Ra was pleased. He had never

made a better one.

But now it was finished he had time to feel hungry. He wondered about

the hunt, and felt uneasy. All his instincts, all the ways of his tribe,

told him that when he was hungry he must hunt. He shook his head, and

took up the long flake of flint he had laid aside before. This had flat

straight edges already, because of the way it had split from the block.

Ra took careful aim, and sharpened the end of it with a single blow

which nicked a diagonal chip from the end. Then he took it, and went up

to the forest to cut more brushwood for his hut.

Ra finished his roof, and tied it down securely, and gathered a pile of

pebbles for a hearth. All day the women and children stared at him

curiously, for it was a new thing for man or boy to stay away from the

hunt. And all day Ra’s ears were pricked for any sound of the men

returning.

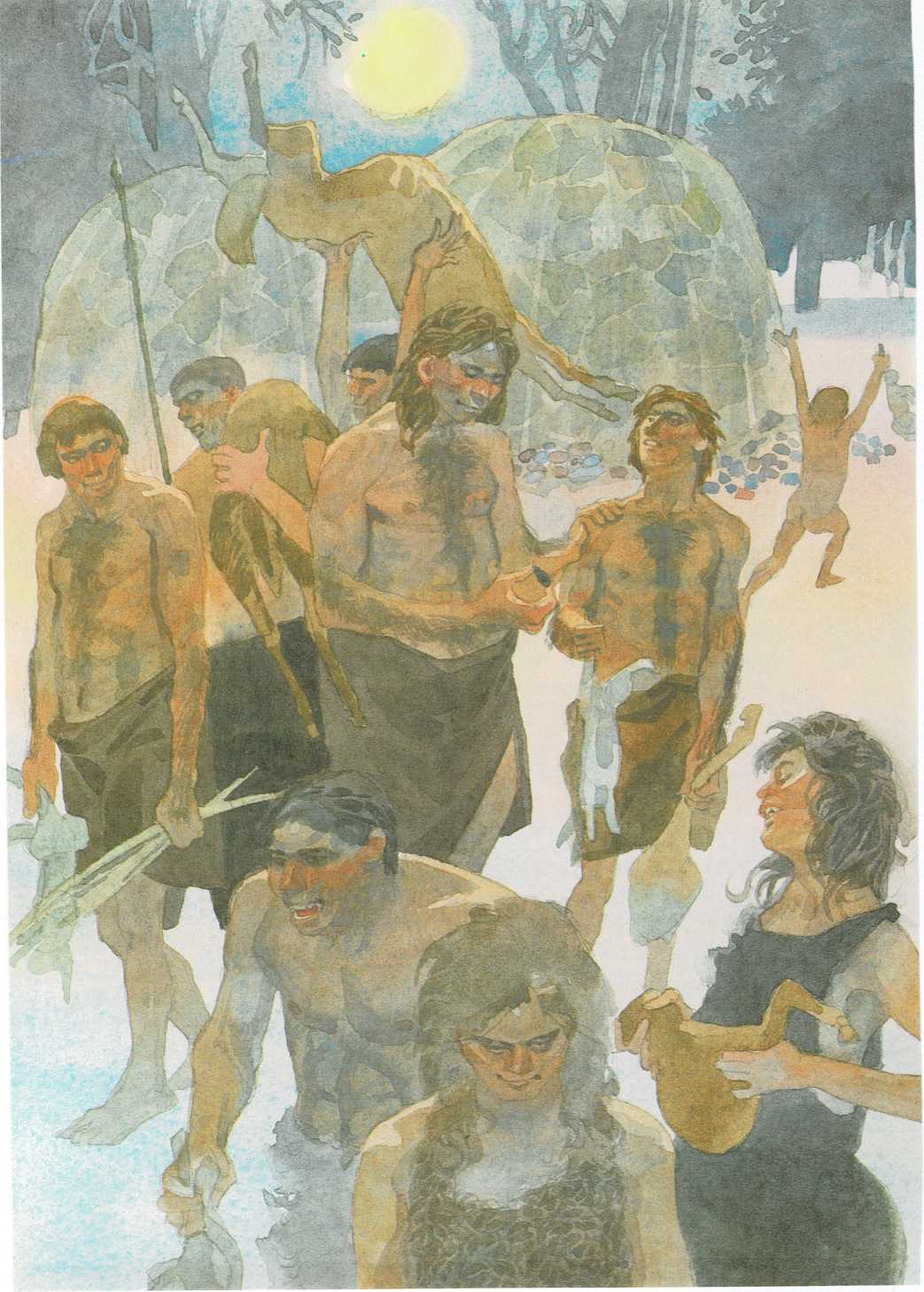

At last he heard them. Down the valley, from among the trees, came the

sound of singing—a low droning song. The hunt had been good. The

hungry families gathered at the hut doors to watch the hunters come.

They marched out of the woods, and scrambled up the slope to the camp,

bringing the carcasses of deer and rabbits across their shoulders. Ra

looked at them hungrily, and licked his lips. He was apprehensive—

what if Yul did not keep his unheard-of bargain? The

night would be cold, and the cramps of hunger in his stomach would keep

him awake. But Yul brought him the flank of a young doe, and half a

rabbit, and exclaimed in delight when he saw the spearhead Ra had made

for him.

“This bargain is good,” he said.

Ra gathered firewood, and stacked it on his hearth of stones, and went

to the Great-grandmother’s house to get fire; for all the fires of his

tribe were lit from hers, and hers had been carried on torches of pine

wood all the way from the winter caves. He roasted his meat on a spit

over the fire, not taking long about it, for he liked it still red and

raw in the middle. He grunted with pleasure as he sunk his teeth into

it, and when he had finished and sat sleepily beside his fire, the good,

well-fed feeling spread through his limbs. He just sat enjoying this

feeling for a long time, and then he built up his fire so that it would

last the night, for it is not only men who hunt for food, and Ra knew

that he did not wake quickly when he was not hungry. Then he crept into

his hut to sleep. He did not fall asleep at once. He felt odd. Never in

all his life before did he remember sleeping well-fed, and yet not tired

from running in the hunt all day. But although the strange feeling was a

new thing, he liked it.

Ra’s new way of life has serious consequences, as you will discover when

you read the rest of the book Toolmaker. Jill Paton Walsh is an

English author with a wide knowledge of historical periods. You may also

like another of her books, Island Sunrise: Prehistoric Cultures in the

British Isles. For another view of the Stone Age, try The First

Farmers in the New Stone Age by Leonard Weisgard.