The Sheep with the Wooden Collar

a French-Canadian folk tale from sashes red and blue by Natalie

Savage Carlson

Little Jean-Baptiste LeBlanc began feeling like one big man when he had

a brother smaller than himself. The new Nichet was not a playmate for

him yet, but Jean-Baptiste did not mind that.

He carried his little brother about in his arms. He talked to him and

sang a song to him about a gray hen who laid her coco^1^ in the church

just for Nichet.

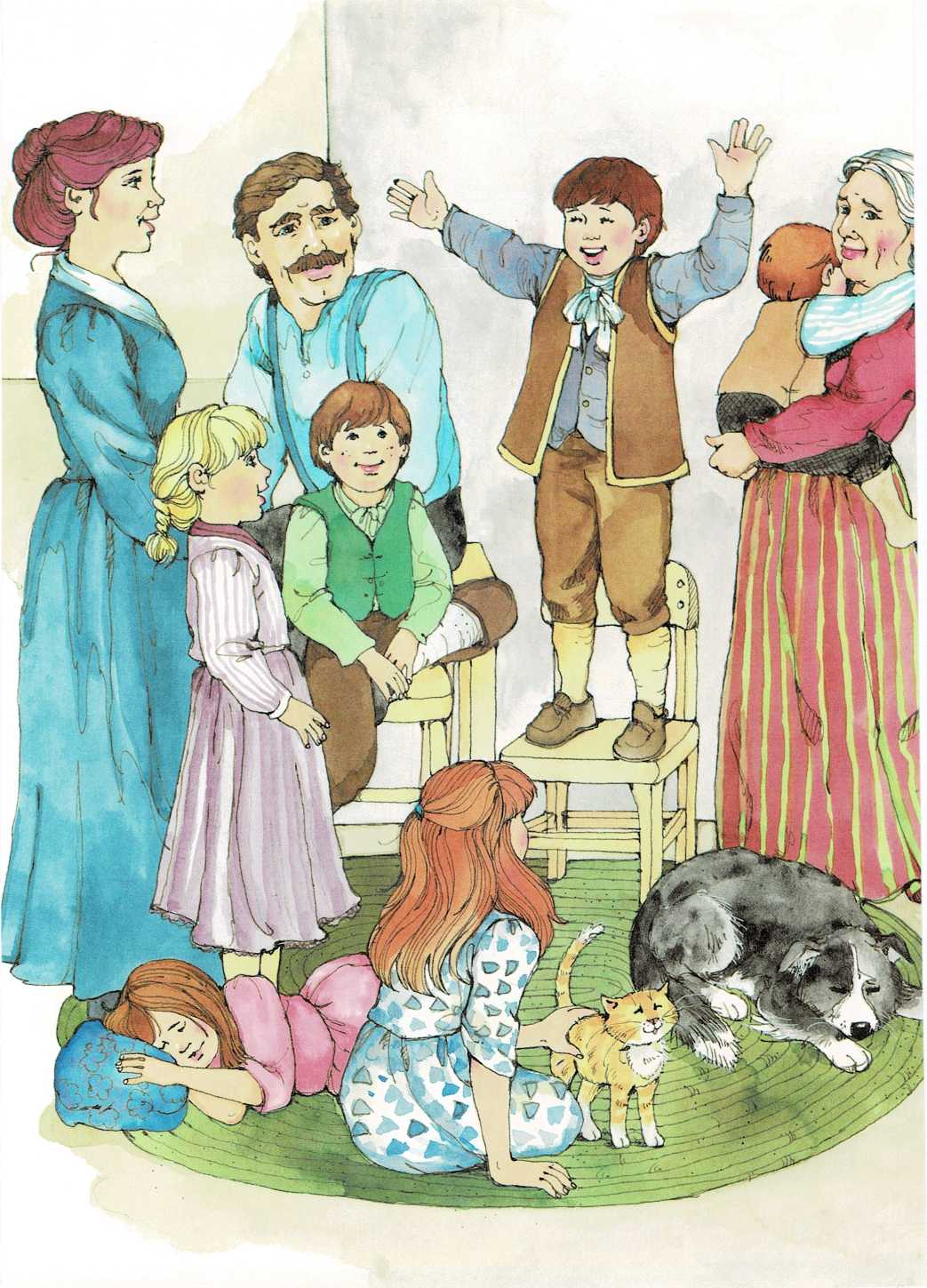

When all the LeBlancs went to a stay-awake party given by the neighbors,

Jean-Baptiste was made the special watcher of the new little nest egg.

Now that he was such a big boy, he was able to stay awake later at the

parties. He was able to sing songs with the others and listen to the

exciting stories told by the old heads. Stories about fearsome loups

garous[^1] [^2] and lutins[^3] [^4] [^5] and fi-follets ‘.

Jean-Baptiste began wishing he could tell such stories. He often thought

about this as he rocked his little brother or played with his pet

whistler, who woke up in the spring and still remembered how to dance.

He thought about the exciting stories as he did his chores around the

farmhouse. He was thinking about them the day his father sent him and

his dog Toutou\” to the river pasture to drive home the sheep.

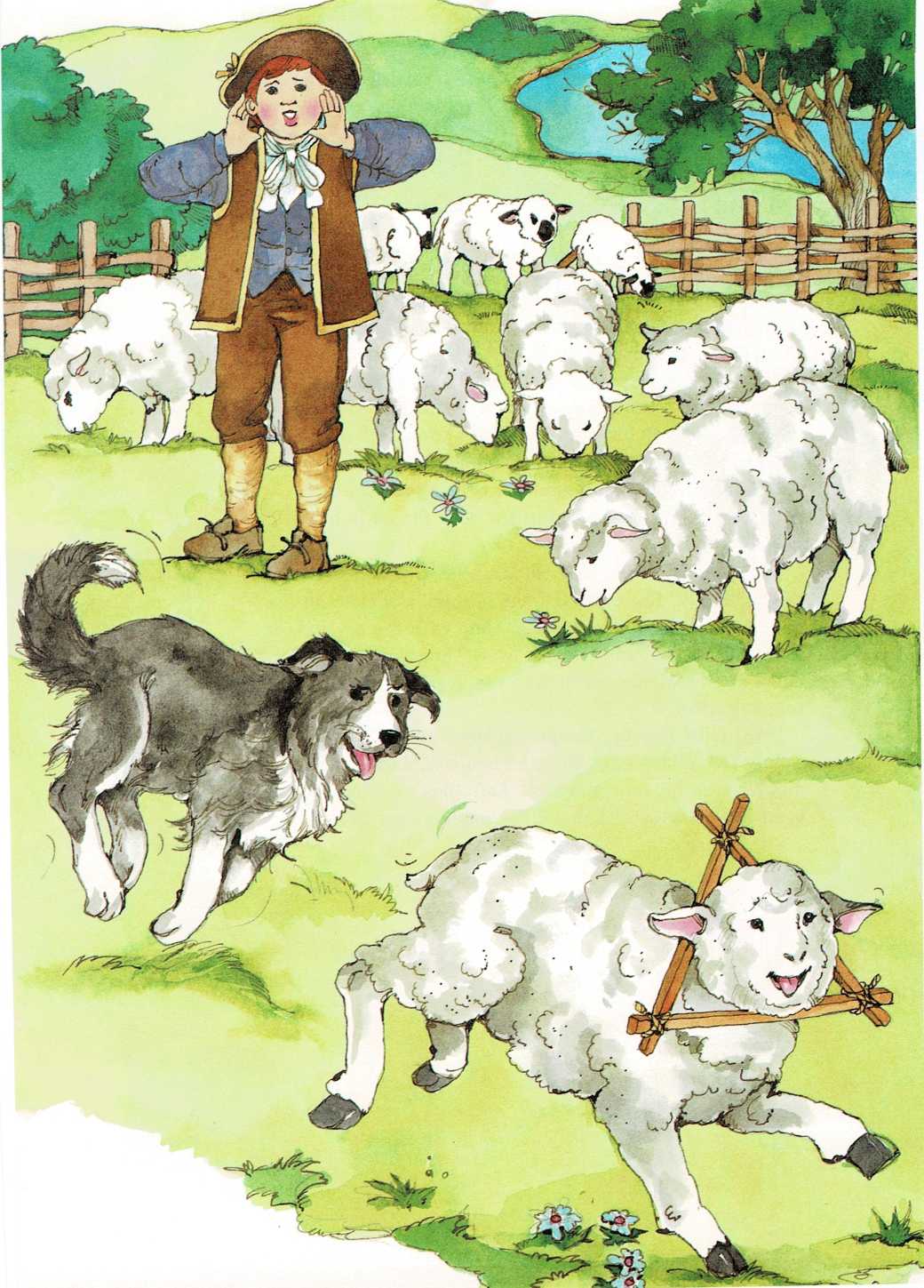

Jean-Baptiste leaned on the woven fence that leaned on the ground.

He watched the sheep nibbling the fresh grass and bleating about nothing

at all. He watched the marbly-eyed gray sheep who wore a wooden collar

around her neck.

“That sheep has a mind of her own,” his father had said. “It is not bad

for a cow or a chicken or a horse to have a mind of its own. But when a

sheep has a mind of her own, she begins jumping over fences.”

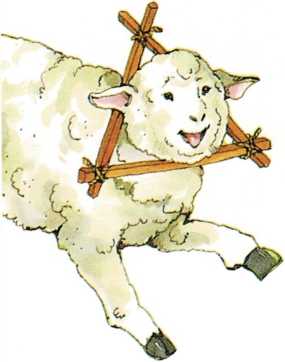

So the sheep with her own mind had to wear a wooden collar so she

couldn’t jump over the woven fence.

She had her own mind with her this late afternoon. “Moute, moute!”

Jean-Baptiste called to the sheep.

All the other sheep were ready to follow tails home, but the one with

the wooden collar had her own idea. She ran back and forth across the

pasture, lifting her hoofs and lifting her tail.

Toutou was right behind her, nipping at her hoofs as they went up and

down. First she ran away to the north. Then she turned east. Finally she

turned south and followed the other sheep to the road.

Jean-Baptiste thought about this as he and Toutou walked in the dust of

the sheep.

“Be! Be!” bleated the other sheep in a chorus, as if they were singing a

round.

But the sheep with the mind of her own didn’t sing one “be.” She tossed

her wooden collar. She lifted her hoofs and she lifted her tail. She ran

along by herself.

Jean-Baptiste decided to make his story about her. As his worn moccasins

scuffed in the dusty sheep tracks, his mind made up the story. He could

hardly wait to get home to tell it to his father.

He didn’t have to wait that long. Luc Boulanger came driving his

two-wheeled cart toward them. When he met the sheep, he saw that he

couldn’t go any farther until they were past him. So he stopped his

horse.

The sheep on the right wanted to pass him on the left. The sheep on the

left wanted to pass him on the right. They bumped into each other and

followed tails around Luc Boulanger’s cart. They made two streams of

wool, as if the cart were a canoe in the middle.

J

“Be! Be!” bleated the sheep following tails.

But the sheep with the wooden collar didn’t say a single “be.” She just

lifted her hoofs and lifted her tail until she came to Luc Boulanger’s

horse. Then she dropped her hoofs and dropped her tail. She would not go

any farther. Luc Boulanger snapped at her with his whip, but that only

frightened his horse.

“That is a stubborn sheep you have there,” said Luc to Jean-Baptiste.

Jean-Baptiste put his hands in his pockets and looked up at Luc.

“She is a very strange sheep also,” said the boy. “I did not think I

would get her this close to home. She wouldn’t leave the pasture with

the other sheep. She ran

north and grew as big as a yearling calf. She turned east and grew as

big as a horse. She turned south and grew as big as a house. So,

believe me, the other sheep and I started to run down this road as

fast as our feet would take us. And Toutou ran too. He was afraid of

that sheep as big as a house.”

Luc Boulanger’s eyes were almost as big as his ears at this tale. He

backed his horse way over to the side of the road. He squeezed himself

into the farthest end of the seat as the sheep with the wooden collar

went by, lifting her hoofs and lifting her tail.

Jean-Baptiste and Toutou drove the sheep up the LeBlanc lane to the

barn. The boy opened the door and the dog drove the sheep through it.

Then the little boy kicked up his moccasins like a frolicky lamb

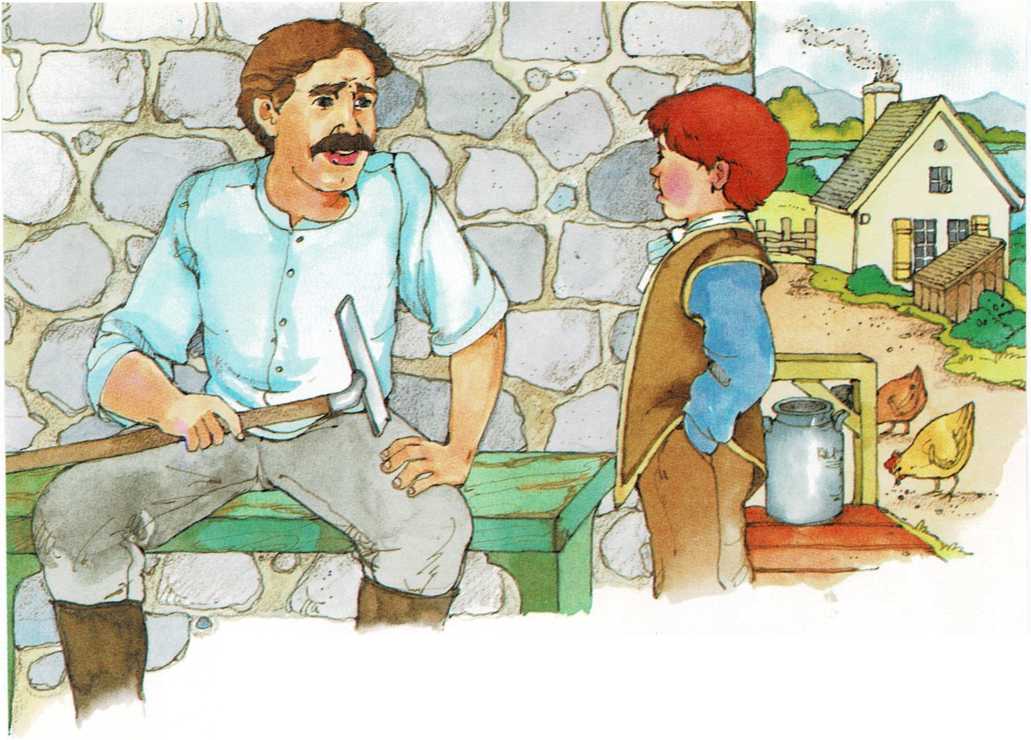

himself. He ran to find his father. He found him mending a broken hoe

near the back door.

Jean-Baptiste put his hands in his pockets and looked up into his

father’s face.

“Papa,” he said, “something very strange happened today.”

“Did that sheep jump the fence even with the wooden collar on her neck?”

asked Jean LeBlanc.

“No, Papa, it was stranger than that,” said the boy. “When I went with

Toutou to get the sheep, she tried to run away from us. She ran north

and grew big as a yearling calf. She turned east and grew big as a

horse.

She turned south and grew big as a house. It really stretched my eyes,

Papa.”

“My faith,” cried Jean LeBlanc. “The sheep is bewitched. I always

thought there was something strange about a sheep having a mind of her

own. Do not

go near her alone.”

All the other LeBlancs were told about the sheep. \’ ”

“She ran north and got big as a yearling calf,” repeated Jean-Baptiste,

with his hands in his pockets. “She turned east and grew big as a horse.

She turned south and grew big as a house.”

The little LeBlancs began to howl.

“She is a loup garou,” cried Marie-Elaine. “We are living on a farm

with a loup garou.”

“The lutin must be riding her,” cried Pierre-Paul.

Mamma was sitting in the rocking chair feeding the new Nichet some

gruel. She held the baby closer so that the sheep could not get him.

“Poush!” said Grandmere. “A sheep is a sheep. How could a stupid sheep

grow big as a horse or a house? Come here, Jean-Baptiste. Let me feel

your forehead. Perhaps you have a fever.”

But no one listened to Grandmere because a fever is a dull thing while a

bewitched sheep is an exciting one.

Luc Boulanger came over next day. He came on his own two legs. He kept

looking uneasily toward the barn.

“Jean LeBlanc,” he said, “that sheep with the wooden collar stood in the

road and stared at my horse. Now my horse has gone lame.”

Jean LeBlanc was sorry about the lame horse. He offered Luc Boulanger

the loan of his own horse.

It wasn’t long before Luc Boulanger was back again.

“Jean LeBlanc,” he said, “you remember how your

bewitched sheep nibbled a leaf off my apple tree as she went down the

road this morning. Now all the leaves are turning brown and I think the

tree will die.”

Jean LeBlanc could sympathize with his neighbor about the apple tree.

What is as good as an apple baked in pastry or eaten raw in its own red

skin?

“I will see that you get some of my apples this summer,” he offered.

Everyone told Jean LeBlanc what to do about his sheep. But Jaco Pichet,

the butcher, had the best cure for a bewitched sheep.

“Bring her to my place,” he said, “and I will butcher her. She will no

longer run north and east and south. And I have yet to see the mutton

chops that grew any bigger after they left the butcher’s scales.”

Jean LeBlanc agreed that this was the best thing to do about the sheep

with the wooden collar.

He asked Jean-Baptiste to help him get her to the butcher because all

the sheep were used to the little boy.

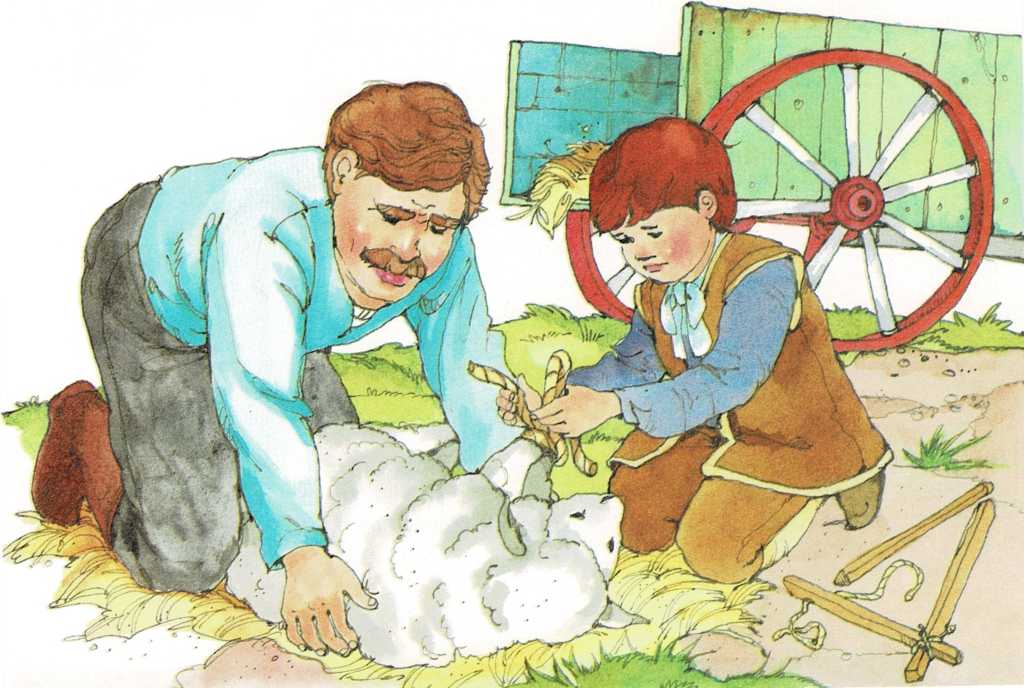

Jean-Baptiste helped his father unfasten the wooden collar from the

sheep’s neck. He helped tie her hoofs together. He helped lift her into

the two-wheeled cart. And all the time that Jean-Baptiste was helping,

he had an unhappy look on his small face.

He sat quietly beside his father on the seat of the cart. His head hung

low. He did not ask any questions.

“Be-e-e,” cried the sheep in protest, as the cart rode over a stone in

the road.

Jean-Baptiste could not stand himself any longer. “Papa,” he said in a

low voice, “I have something to tell you.”

“Did you forget to close the barn door?” asked his father.

“Worse than that, Papa,” said Jean-Baptiste. “The sheep we are taking to

the butcher did not go north and get big as a yearling calf. She did not

turn east and grow big as a horse. She did not turn south and grow big

as a house. She only ran around in the pasture lifting her hoofs and

lifting her tail.”

Jean LeBlanc pulled on the reins. The horse stopped and the cart

stopped.

“Jean-Baptiste,” said his father sternly, “you have been telling one big

untruth about the poor sheep.”

The boy miserably nodded his head. “I don’t want her to go to the

butcher, Papa,” he said. “She never does anything wrong but jump over

fences. And she looks so gay when she runs across the pasture lifting

her hoofs and lifting her tail.”

Jean LeBlanc turned the horse around. The road was not wide so he had to

make the horse and cart go back and forth several times before they were

headed for home again.

“It is a wicked thing to tell an untruth, Jean-Baptiste,” said his

father.

The boy nodded some more. Then he fell into deep thought. As usual his

deep thought was followed by questions.

“Papa,” asked Jean-Baptiste, “is it an untruth when the old heads say

that they were chased by the loup garou? Was Michel Meloche telling a

big untruth when he said that a boat of ghostly fishermen went flying

through the clouds?”

Jean LeBlanc suddenly became very busy with his horse. He yelled at her

and jerked at the reins as if she were running away.

“My faith, must you spill us into the ditch?” shouted Jean LeBlanc,

although his horse wasn’t doing anything but jogging along in the middle

of the road.

Jean-Baptiste sat waiting for his father’s answer.

His father settled back into the seat again. He changed the reins from

one hand to the other. He cracked the whip over the horse’s back. Flic,

flac. Then he smiled wisely at his little son.

“The old heads and Michel Meloche do not tell untruths, my little

cabbage,” he said. “They tell stories.”

“What is the difference between an untruth and a story?” asked the boy.

“Ho, ho, there is a great difference,” said his father, getting busy

with the horse again.

“But what is the difference, Papa?” insisted Jean-Baptiste.

The wise look which the boy knew so well crossed his father’s face

again.

“The difference is in the way one tells it,” said Jean LeBlanc. “When a

man tells an untruth, he stands still with his hands in his pockets and

his eyes in one place. But when a man tells a story he waves his arms

qa [^6] and rolls his eyes qa. Then all the people know that they

can believe it or not—as they wish.”

Jean-Baptiste was satisfied with this explanation.

Soon they were home and the boy had to confess to the whole family that

he had told an untruth about the sheep with the wooden collar.

Mamma scolded him and the other children were

ashamed of him. But Grandmere could understand exactly how it had

happened.

She took Jean-Baptiste into her own room and did some more explaining

about untruths and stories.

“It is like this, Jean-Baptiste,” she said. “You have often heard that

when our people first came to Canada, they were surrounded by dangers.

There were hostile Indians and fierce animals and new sicknesses. But

these dangers were not enough for people as strong and brave as ours.

They needed more dangers so they made up loups garous and lutins and

fi-follets. And all the other creatures that only people as smart as

ours could think up.” Grandmere patted the little boy’s head. Then she

untied the strings of the round black cap on her head. “But as far as

your old Grandmere can see, they are only fancy untruths,” she added

tartly.

So the sheep had her wooden collar put on her neck again and she went

back to the pasture with the others.

Everything was explained to the neighbors in a way which did not shame

little Jean-Baptiste. It was done at the Boulangers’ stay-awake party

one pleasant summer evening. It was a gay fete, with tables full of food

and floors full of dancing feet and children.

Old Pierre Boulanger played his violin and even the grandmeres danced to

that.

When all the feet were tired of dancing and half of the children were

asleep, Luc Boulanger waved his hands for quiet.

“A story,” he cried. “Who will tell us an exciting story?”

Then Jean LeBlanc rose to his feet and proudly looked down at his

next-to-the-littlest son.

“Jean-Baptiste has a story,” he announced. “Only a few have heard it so

far, but tonight he will tell it to everyone.”

He stood the boy on a chair so everyone could see him. Then he sat down

again.

Jean-Baptiste blinked like a little owl pulled out of its

tree hole. Then he began to wave his arms qa and roll his eyes qa.

“We have a strange sheep,” he said. “Only last week she did a marvelous

thing which I saw with my own eyes. I had gone to the pasture with

Toutou, our dog, to bring home the sheep.”

Faster waved Jean-Baptiste’s arms qa and faster rolled his eyes qa.

“But the sheep with the wooden collar would not follow the other sheep.

She ran away from us. She went north and grew big as a yearling calf.

She turned east and grew big as a horse. She turned south and grew big

as a house. Then there was a terrible clap of thunder, and lightning

flashed all around that great sheep. Fire came out of her eyes and—my

faith, I ran home then.”

Everyone laughed and clapped. Luc Boulanger laughed and clapped the

loudest. He knew now that the sheep was not really bewitched. Everyone

knew that there was nothing wrong with the sheep with the wooden collar

except that she liked to jump over fences.

Luc Boulanger patted Jean-Baptiste on the back. “You are one fine

storyteller,” he said. “When you get big, you will be as good as old

Michel Meloche.”