Rosa-Too-Little

by Sue Felt

It was winter. The snow was piled in shapeless mounds along 110th

Street.

But it wasn’t the snow that bothered Rosa as she

followed Margarita up the library steps into the warm indoors.

For as long as she could remember Rosa had been following her big

sister, Margarita, to the library.

And every time Rosa waited while Margarita returned her books.

And every time she waited Rosa was sad. She wanted very much to have

books of her own to return.

“Please, Margarita,” she would say, “when can I join?” “You are too

little, Rosa. You have to write your name and get a card before you can

take books out.”

“Oh, there is Peter Rabbit in bed,” Rosa would say,

“and there is Mrs. Rabbit making him some Camomile

Tea and Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail are eating bread and milk and

blackberries.”

“It is always the same. Last winter I was too little. Last summer I was

too little. Why am I always too little to have my own books?” Rosa

sighed.

Rosa was big enough to help her mother at home while Margarita and

Antonio were at school. But whenever Margarita came from school to take

her to the library, Rosa was ready.

Always before Margarita chose new books she would hold Rosa up to press

her face against the cool glass to look into that small other world of

the Peep Show.

On Fridays Margarita and Antonio went to Story Hour upstairs while Rosa,

who was too little, sat in the Reading Room looking at Picture Books.

She looked at the pictures until she knew every one by heart. This made

Rosa sad, too. She was certain that if she could only have her own

library card and take home her own books she would be able to read them.

She wanted so

much to go to Story Hour, too, and hear the library teacher tell fairy

tales. Sometimes Margarita told Rosa the stories or read them to her at

home. But Rosa knew it was not quite the same as hearing them at Story

Hour. She was sure she must be nearly big enough to make a wish and help

blow out the candle after Story Hour. Antonio had told her about that

part, too.

“Oh, how I would like to do that. Why am I always too little?” Rosa

sighed.

The snow melted. After light spring rains the trees in Central Park were

fringed with baby green leaves.

Margarita carried her jump rope to school and often played double Dutch

on the sidewalks in the evenings as the nights grew warmer.

And Rosa was too little for jump rope.

When Margarita wasn’t jumping rope she was roller skating. And Mother

said Rosa was too little for roller skates.

It seemed to Rosa she was too little for anything. Antonio and his

friends once again were training their pigeons on the rooftops. Antonio

and his friends didn’t want her on the roof. And Antonio was too busy to

take her to the library. No one would take her to the library. And that

was what Rosa wanted to do most of all.

She was sad.

Rosa begged and begged her mother to let her go alone to the library.

Finally one day her mother said yes.

Rosa could go all by herself. She remembered to wait for the green

lights crossing the street. She remembered to wait in line. She was very

proud to do it all alone.

But when at last she reached the desk and the library teacher asked for

her books, Rosa suddenly remembered something else.

Rosa Maldonado did not have any books; she did not even have a library

card. She was too little to join. Poor little Rosa covered her face,

pushed her way out of the line, and ran down the stairs, out the door,

and all the way home.

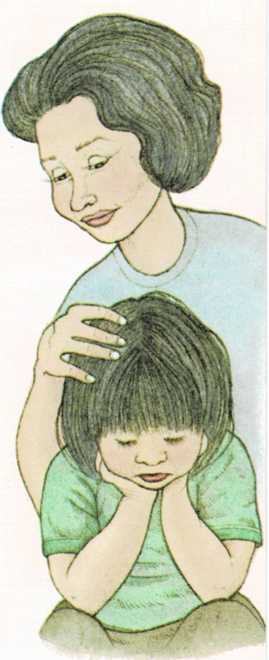

“Rosa, little dear, what is the matter, chiquita?” her mother asked.

Rosa sobbed louder, but at last her mother understood.

“Rosa,” she comforted, “we will make a plan, a secret for you and me!”

And Rosa was not quite so sad!

The next day was hot, but Rosa and her mother didn’t mind. They started

their plan.

All through the long, hot, city summer Rosa worked on her plan except

for the days when the street-cleaning men turned on the water hydrant,

the Pompa, Rosa, Margarita, and Antonio called it. Then they rushed

through the fast, cold spray of water. The pavement was cool on the

soles of their feet.

Most of the children forgot about books, but not Rosa.

Sometimes in the afternoon Margarita took Rosa to hear the Picture Books

read in the library. Everything was quiet in the summer. There were not

so many children, for\’some of them were in camp and some were in the

country and all the rest were too hot and sticky to do much of anything.

Rosa listened to the stories and smiled inside with her secret.

And every day Rosa worked on her plan in a special corner at home so

that Margarita and Antonio wouldn’t guess.

One day Mama said:

“When school starts in September, Rosa may go with

Margarita and Antonio.”

Then Rosa smiled. She was not too little any more.

She could hardly wait.

The last day before school was to begin the little penny merry-go-round

came. La machina, the children called it. Everyone on 110th Street who

had pennies had a ride, and the others followed the music. But they

weren’t so happy as when la machina had been there in the spring.

Playtime was over—no more long days of jump rope, marbles, skating,

and stoopball.

But Rosa skipped with joy.

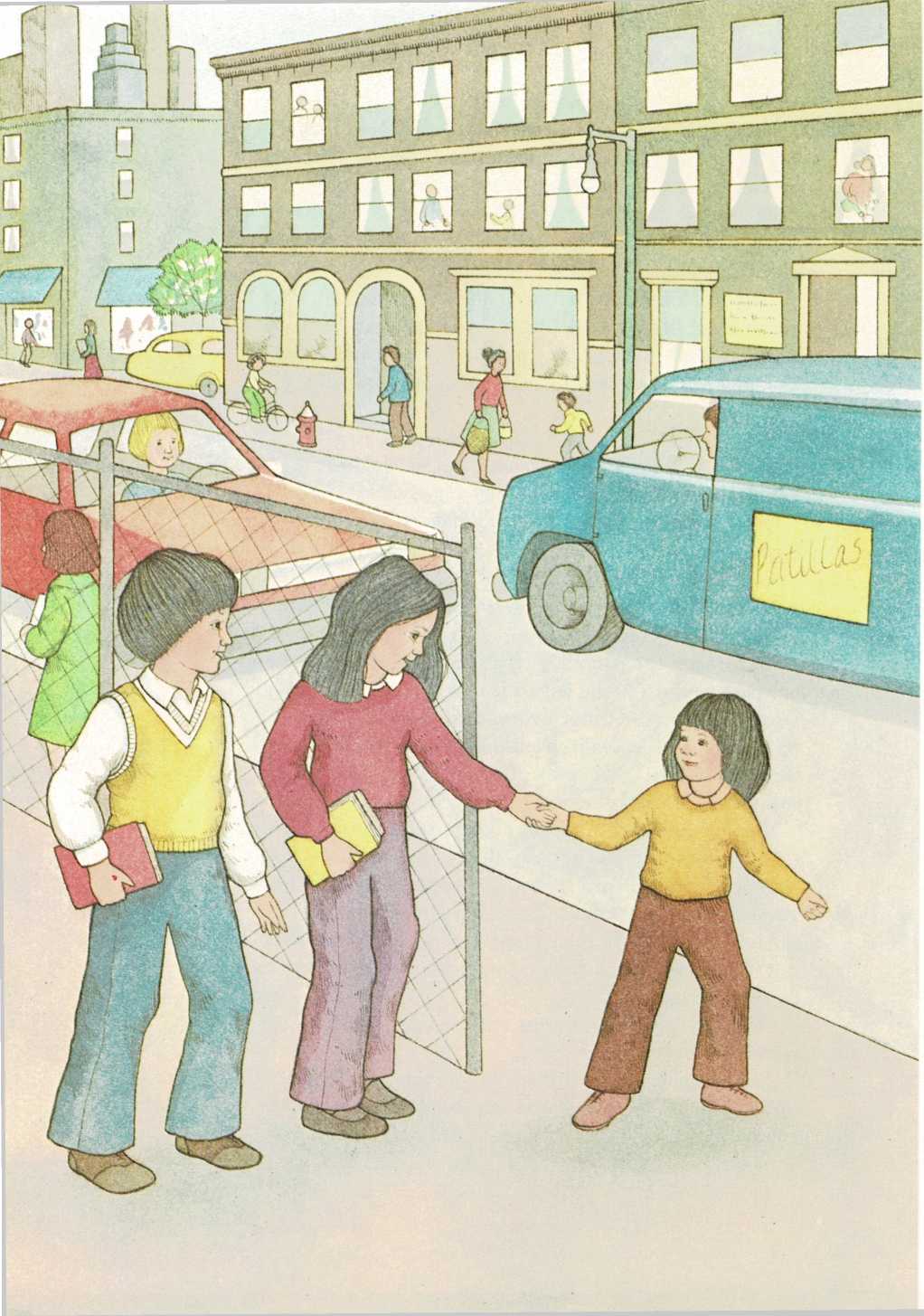

On Monday school started, and Rosa walked with Margarita and

Antonio—quiet and proud. It was very exciting to be in school, but

there was something else Rosa wanted to do, too.

At three o’clock she waited by the playground gate till Margarita and

Antonio came out and then Rosa pulled her sister’s hand.

“Margarita, Margarita, today may I go?”

“Rosa, what are you talking about? How do you like school?” said

Margarita.

“It’s wonderful. But Margarita, today may I go to the library with you?”

asked Rosa, still pulling her sister’s hand.

“But Rosa,” said Margarita, “why today? I have homework to do.”

“Please, Margarita.” And finally Margarita gave in to Rosa’s pleading

and they went together to the library.

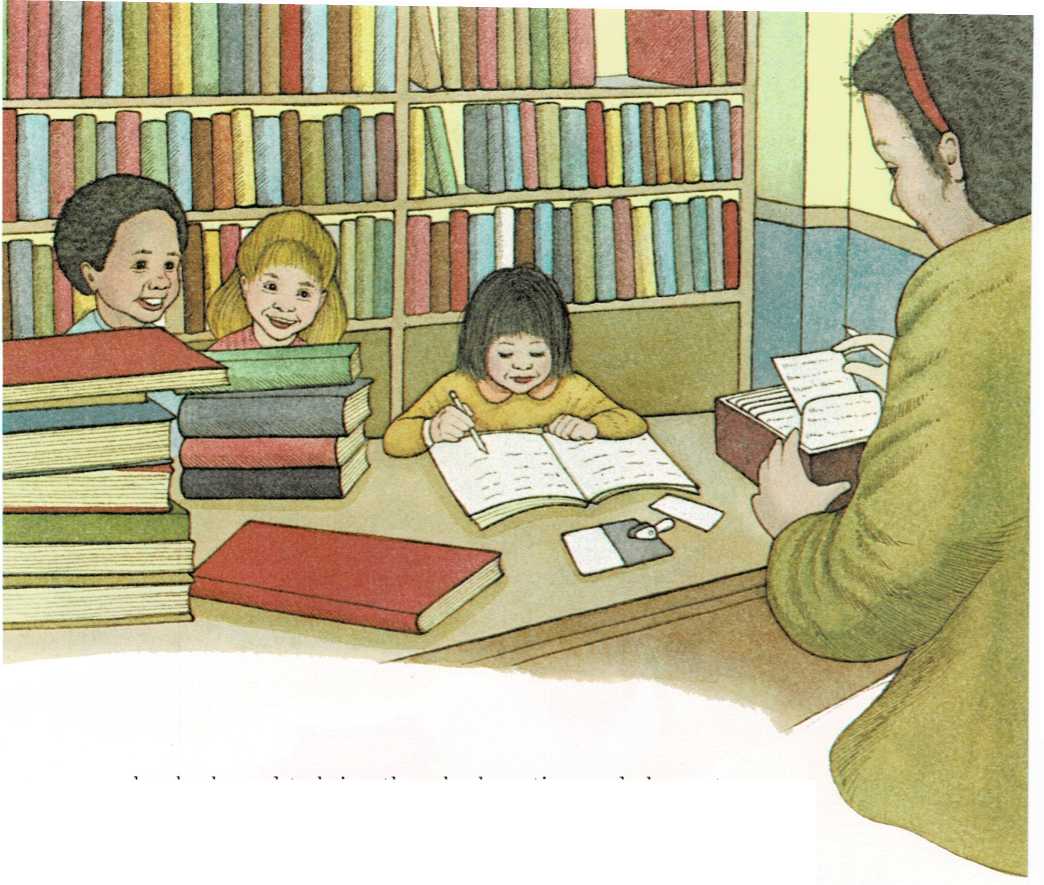

Lots of boys and girls were back again to get their cards after the

summer. Soon Rosa’s turn came.

“What do you want, Rosa?” asked the librarian, who had seen Rosa so many

times she knew her name.

“I want to join, please,” said Rosa.

“Oh, but Rosa, you are very little. You must be able to write your name,

you know.”

“I can write my name,” Rosa said proudly.

The library lady smiled and took a white slip of paper

from a drawer, dipped a pen in the inkwell, and said: “Write your name

on this line, Rosa.”

Rosa held tight to the pen and carefully, carefully made the letters.

The pen scratched. Rosa wasn’t used to ink, and she wasn’t sure the

librarian could read her name, but when Rosa looked up, the library lady

smiled.

“That’s fine, Rosa,” she said.

“Why, Rosa,” Margarita said, “that’s wonderful!” and she wrote in the

address and school and Rosa’s grade and age.

“Rosa, take this home and have your mother fill out the other side, then

bring it back,” the librarian said.

Rosa ran down the stairs and out the door. She ran all the way home and

into the kitchen where her mother was preparing dinner.

“Mama, Mama, I joined, I joined! I wrote my name and you must sign the

paper so I can get my card.”

Her mother smiled proudly and kissed Rosa’s hot little face. She signed

her name and Rosa’s father’s name on the back of the paper.

The librarian was surprised to see Rosa back so soon.

“I ran,” Rosa said, and showed her mother’s name on the paper. Then the

librarian gave Rosa a blue slip of paper and Rosa wrote her name again.

All the time Rosa saw her name on a brand-new card. It would be all her

own. The library teacher helped her read the pledge:

When I write my name in this book, I promise to take good care of the

books I use in the library and at home and to obey the rules of the

library.

Then Rosa stood on a stool and wrote her name in the big book. That was

the best moment of all, because now Rosa Maldonado’s name was in the

book, the big black book where all the other children who could write

had signed their names.

She listened to the rules carefully, although she already knew them. She

promised to take good care of

her books and to bring them back on time and always to have her hands

clean!

Then Rosa walked over to the Easy Books and found the two books she

wanted. She knew just where to find them.

Rosa then waited in line to have her books stamped. She smiled back at

the library teacher. Then she walked down the library stairs and out

into the brisk evening. She squeezed her very own books.

“I am not too little any more,” said Rosa.

She was very happy.

Tell Me Some More by Crosby Bonsall and Mike’s House by Julia Sauer

are two other good stories about children and libraries. And if you want

to meet another delightful Puerto Rican family, try Friday Night Is

Papa Night by Ruth Sonneborn.