Pinocchio

from The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi translated from the

Italian by Carol Della Chiesa

When Mastro Cherry the carpenter found a piece of wood that laughed and

talked, he gave it to his good friend Geppetto. The kindly old Geppetto

took the wood home, for he wanted to carve a marionette that would dance

and turn somersaults. And so begins the story of the famous—and very

naughty—Pinocchio.

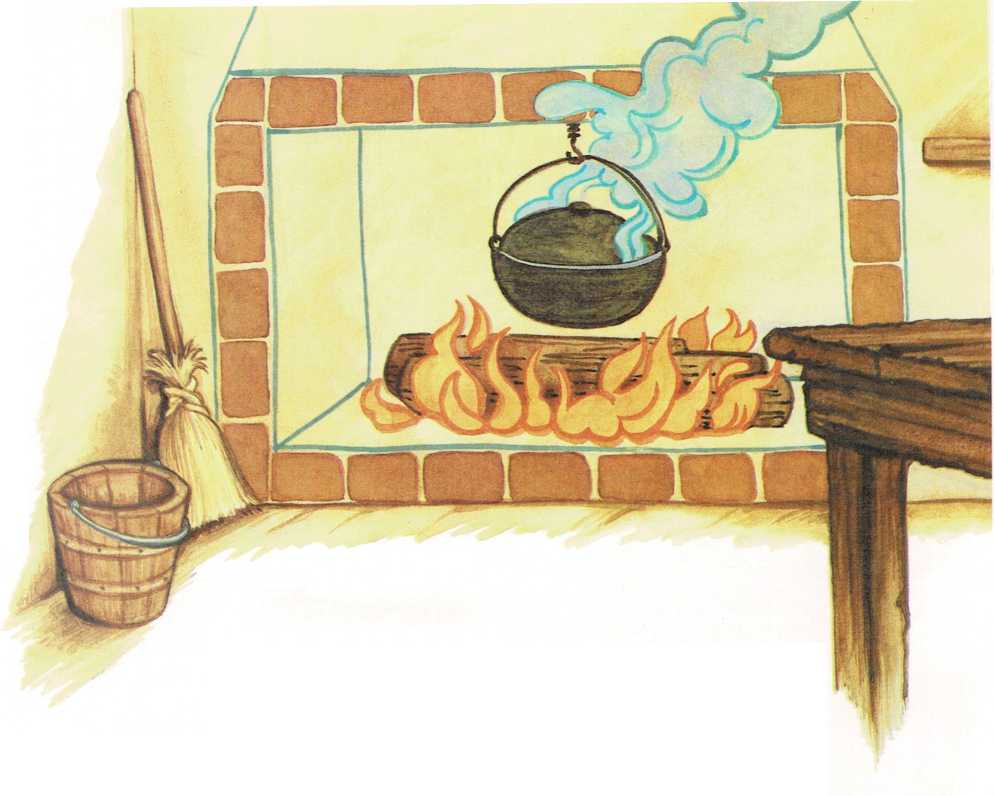

Little as Geppetto’s house was, it was neat and comfortable. It was a

small room on the ground floor, with a tiny window under the stairway.

The furniture could not have been much simpler: a very old chair, a

rickety old bed, and a tumble-down table. A fireplace full of burning

logs was painted on the wall opposite the door. Over the fire, there was

painted a pot full of something which kept boiling happily away and

sending up clouds of what looked like real steam.

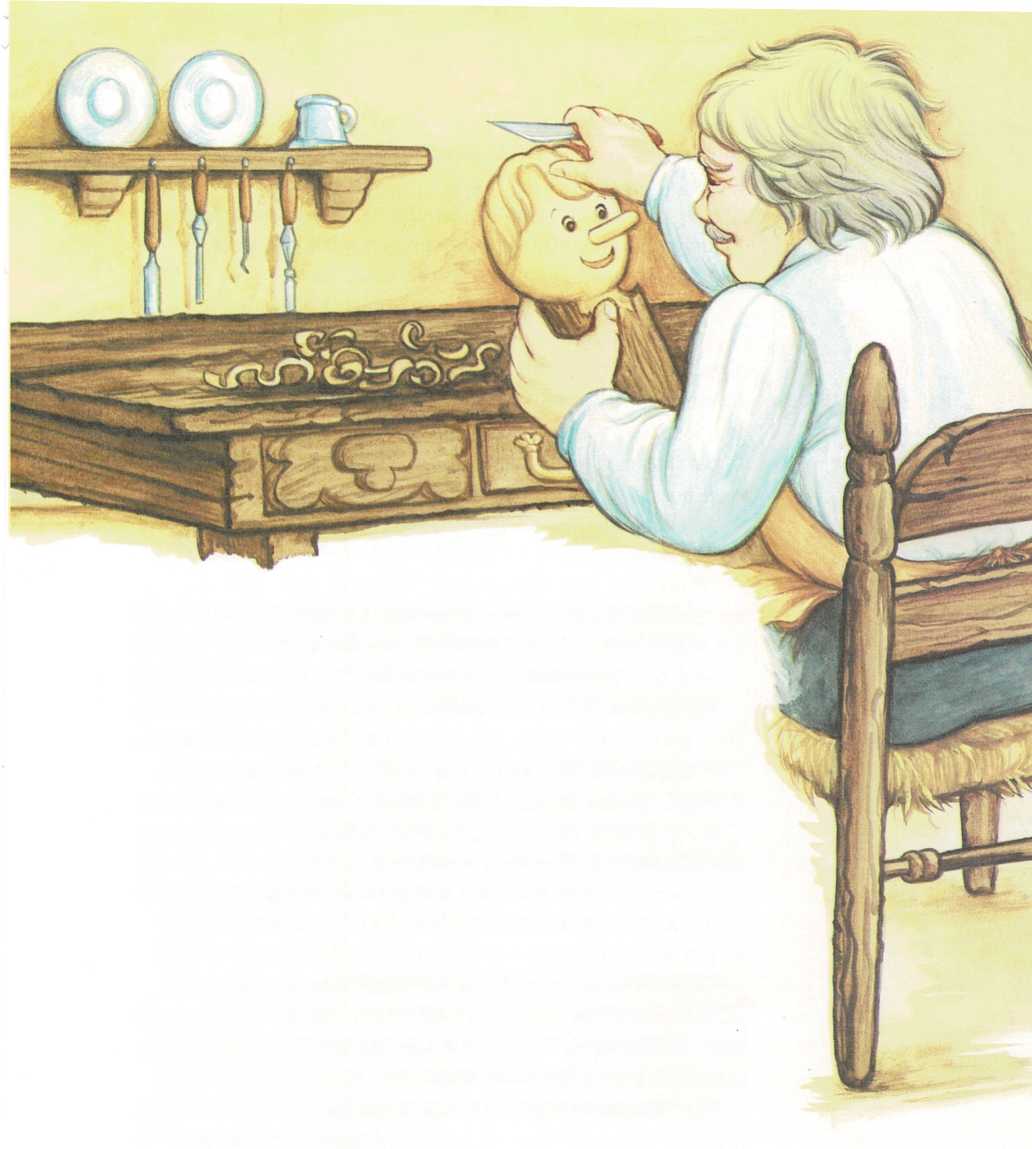

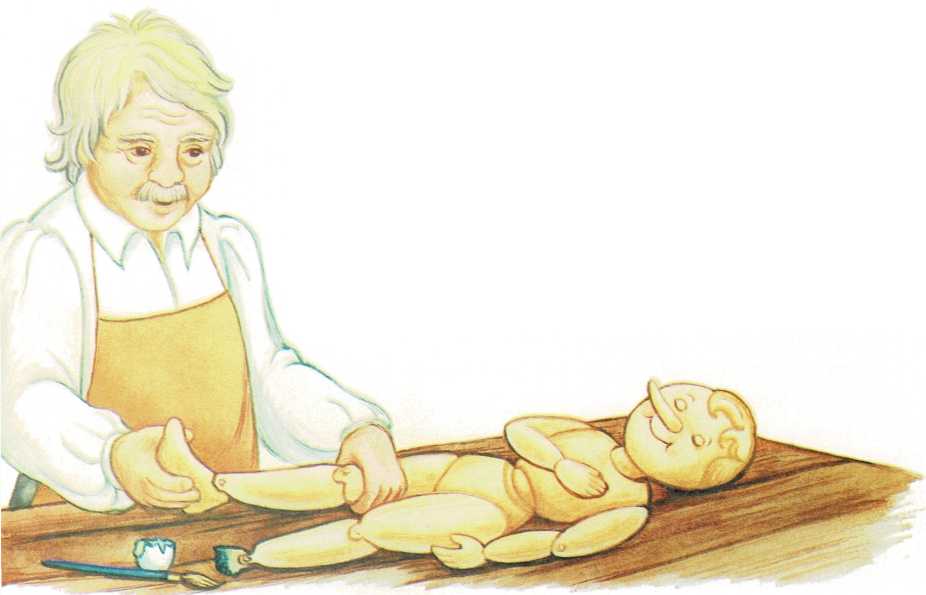

As soon as he reached home, Geppetto took his tools and began to cut and

shape the wood into a marionette.

“What shall I call him?” he said to himself. “I think

I’ll call him Pinocchio. This name will make his fortune. I knew a

whole family of Pinocchi once—Pinocchio the father, Pinocchia the

mother, and Pinocchi the children—and they were all lucky. The richest

of them begged for his living.”

After choosing the name for his marionette, Geppetto set seriously to

work to make the hair, the forehead, the eyes. Fancy his surprise when

he noticed that these eyes moved, and then stared fixedly at him.

Geppetto, seeing this, felt insulted and said in a grieved tone:

“Ugly wooden eyes, why do you stare so?”

There was no answer.

After the eyes, Geppetto made the nose, which began to stretch as soon

as finished. It stretched and stretched and stretched till it became so

long it seemed endless.

Poor Geppetto kept cutting it and cutting it, but the more he cut, the

longer grew that impertinent nose. In despair he let it alone.

Next he made the mouth.

No sooner was it finished than it began to laugh and poke fun at him.

“Stop laughing!” said Geppetto angrily; but he might as well have spoken

to the wall.

“Stop laughing, I say!” he roared in a voice of thunder. The mouth

stopped laughing, but stuck out a long tongue.

Not wishing to start an argument, Geppetto made believe he saw nothing

and went on with his work.

After the mouth, he made the chin, then the neck, the shoulders, the

stomach, the arms, and the hands.

As he was about to put the last touches on the finger tips, Geppetto

felt his wig being pulled off. He glanced up and what did he see? His

yellow wig was in the marionette’s hand. “Pinocchio, give me my wig!”

But instead of giving it back, Pinocchio put it on his own head, which

was half swallowed up in it.

At that unexpected trick, Geppetto became very sad and downcast, more so

than he had ever been before.

“Pinocchio, you wicked boy!” he cried out. “You are not yet finished,

and you start out by being impudent to your poor old father. Very bad,

my son, very bad!”

And he wiped away a tear.

The legs and feet still had to be made. As soon as they were done,

Geppetto felt a sharp kick on his nose.

“I deserve it!” he said to himself. “I should have thought of this

before I made him. Now it’s too late!” He took hold of the marionette

under the arms and put him on the floor to teach him to walk.

Pinocchio’s legs were so stiff that he could not move them, and Geppetto

held his hand and showed him how to put out one foot after the other.

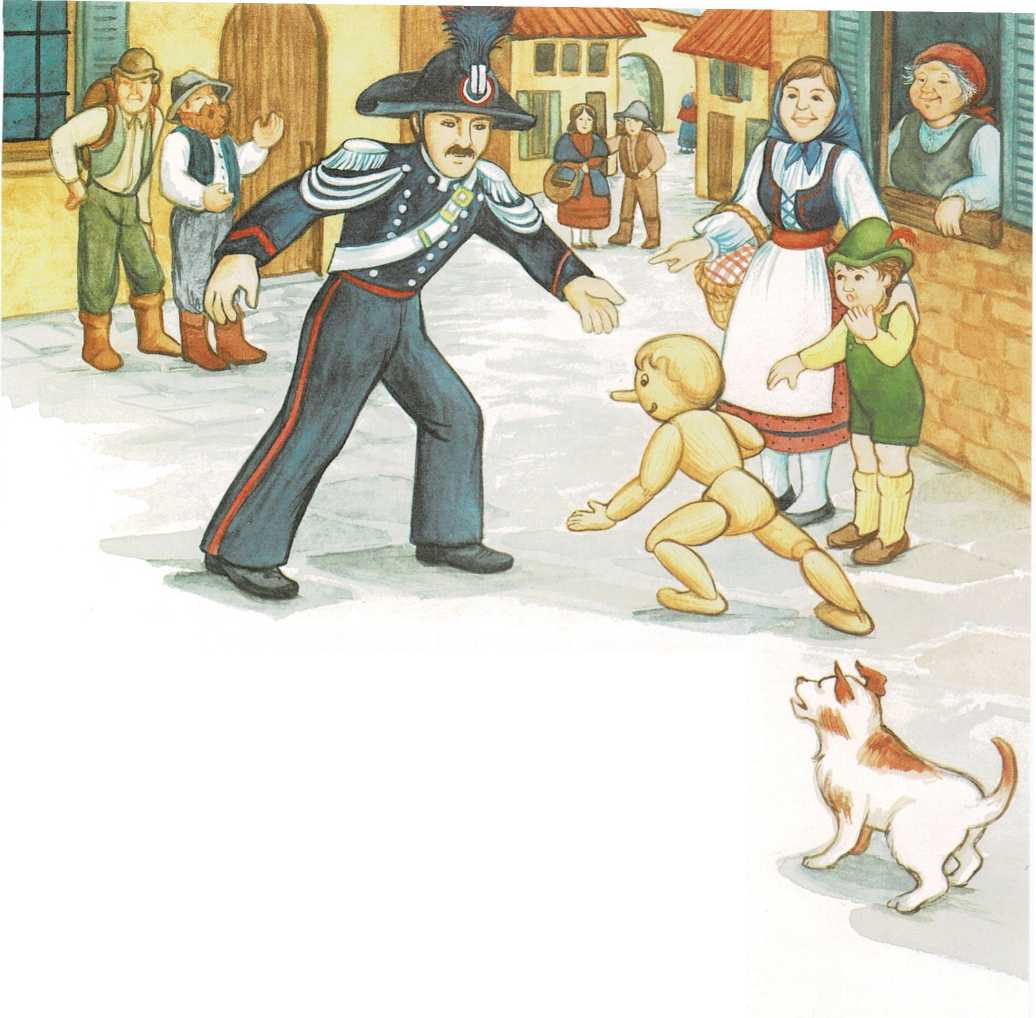

When his legs were limbered up, Pinocchio started walking by himself and

ran all around the room. He came to the open door, and with one leap he

was out into the street. Away he flew!

Poor Geppetto ran after him but was unable to catch him, for Pinocchio

ran in leaps and bounds, his two wooden feet, as they beat on the stones

of the street, making as much noise as twenty peasants in wooden shoes.

“Catch him! Catch him!” Geppetto kept shouting. But the people in the

street, seeing a wooden marionette

running like the wind, stood still to stare and to laugh until they

cried.

At last, by sheer luck, a policeman happened along who, hearing all that

noise, thought that it might be a runaway colt, and stood bravely in the

middle of the street, with legs wide apart, firmly resolved to stop it

and prevent any trouble.

Pinocchio saw the policeman from afar and tried his best to escape

between the legs of the big fellow, but without success.

The policeman grabbed him by the nose (it was an extremely long one and

seemed made on purpose for that very thing) and returned him to Mastro

Geppetto.

The little old man wanted to pull Pinocchio’s ears. Think how he felt

when, upon searching for them, he discovered that he had forgotten to

make them!

All he could do was to seize Pinocchio by the back of the neck and take

him home. As he was doing so, he shook him two or three times and said

to him angrily:

“We’re going home now. When we get home, then we’ll settle this matter!”

Pinocchio, on hearing this, threw himself on the ground and refused to

take another step. One person after another gathered around the two.

Some said one thing, some another.

“Poor marionette,” called out a man. “I am not surprised he doesn’t want

to go home. Geppetto, no doubt, will beat him unmercifully, he is so

mean and cruel!”

“Geppetto looks like a good man,” added another, “but with boys he’s a

real tyrant. If we leave that poor marionette in his hands he may tear

him to pieces!”

They said so much that, finally, the policeman ended matters by setting

Pinocchio at liberty and dragging Geppetto to prison. The poor old

fellow did not know how to defend himself, but wept and wailed like a

child and said between his sobs:

“Ungrateful boy! To think I tried so hard to make you a well-behaved

marionette! I deserve it, however! I should have given the matter more

thought.”

Very little time did it take to get poor old Geppetto to prison. In the

meantime that rascal, Pinocchio, free now from the clutches of the

policeman, was running wildly across fields and meadows, taking one

short cut after another toward home. In his wild flight, he leaped over

brambles and bushes, and across brooks and ponds, as if he were a goat

or a hare chased by hounds.

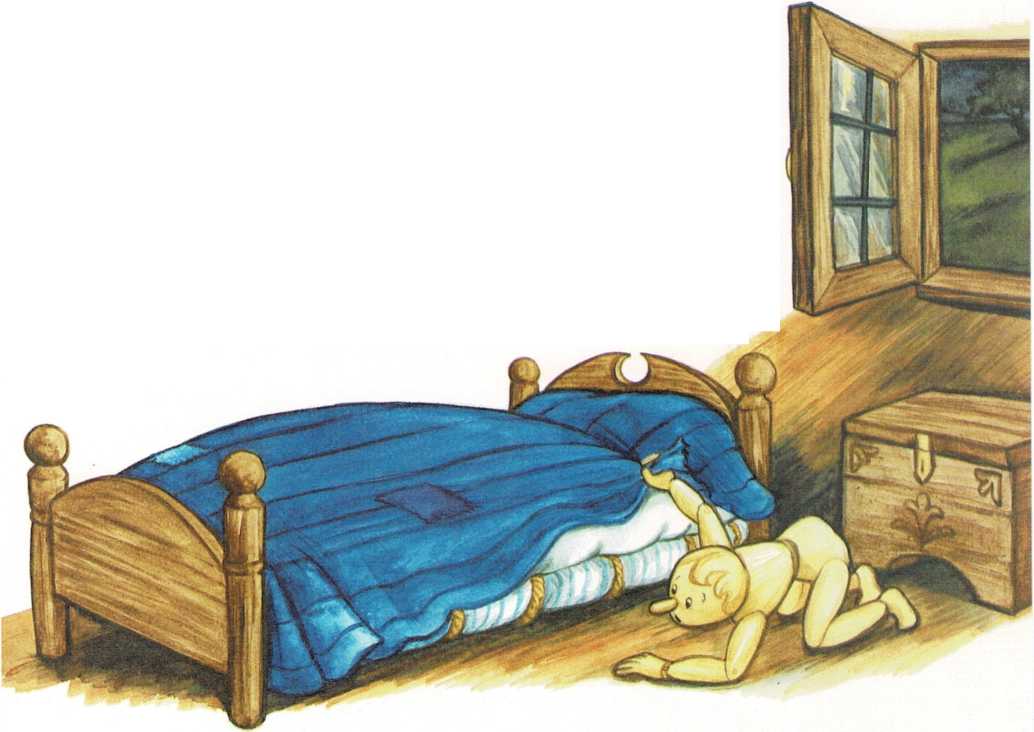

On reaching home, he found the house door half open. He slipped into the

room, locked the door, and threw himself on the floor, happy at his

escape. But, as night came on, a queer, empty feeling at the pit of his

stomach reminded the marionette that he had eaten nothing as yet.

A boy’s appetite grows very fast, and in a few moments the queer, empty

feeling had become hunger, and the hunger grew bigger and bigger, until

soon he was as ravenous as a bear.

Poor Pinocchio ran to the fireplace where the pot was boiling and

stretched out his hand to take the cover off, but to his amazement the

pot was only painted! Think how he felt! His long nose became at least

two inches longer.

He ran about the room, dug in all the boxes and drawers, and even looked

under the bed in search of a piece of bread, hard though it might be, or

a cooky, or perhaps a bit of fish. A bone left by a dog would have

tasted good to him! But he found nothing.

And meanwhile his hunger grew and grew. The only relief poor Pinocchio

had was to yawn; and he certainly did yawn. Soon he became dizzy and

faint.

He wept and wailed to himself: “It was wrong of me to disobey Father and

to run away from home. If he were here now, I wouldn’t be so hungry! Oh,

how horrible it is to be hungry!”

Suddenly he saw, among the sweepings in a corner, something round and

white that looked very much like a hen’s egg. In a jiffy he pounced upon

it. It was an egg.

The marionette’s joy knew no bounds. It is impossible to describe it,

you must picture it to yourself. Certain that he was dreaming, he turned

the egg over and over in his hands, fondled it, kissed it, and talked to

it:

“And now, how shall I cook you? Shall I make an omelet? No, it is better

to fry you in a pan! Or shall I drink you? No, the best way is to fry

you in the pan. You will taste better.”

No sooner said than done. He placed a little pan over a foot warmer full

of hot coals. In the pan, instead of oil or butter, he poured a little

water. As soon as the water started to boil—tac!—he broke the

eggshell. But in place of the white and the yolk of the egg, a little

yellow chick, fluffy and gay and smiling, escaped from it. Bowing

politely to Pinocchio, he said to him:

“Many, many thanks, indeed, Mr. Pinocchio, for having saved me the

trouble of breaking my shell! Good-by and good luck to you and remember

me to the family!”

With these words he spread out his wings and, darting to the open

window, he flew away into space till he was out of sight.

The poor marionette stood as if turned to stone, with wide eyes, open

mouth, and the empty halves of the eggshell in his hands. When he came

to himself, he began to cry and shriek at the top of his lungs, stamping

his feet on the ground and wailing all the while: “If I had not run away

from home and if Father

were here now, I should not be dying of hunger. Oh, how horrible it is

to be hungry!”

And as his stomach kept grumbling more than ever and he had nothing to

quiet it with, he thought of going out for a walk to the nearby village,

in the hope of finding some charitable person who might give him a bit

of bread.

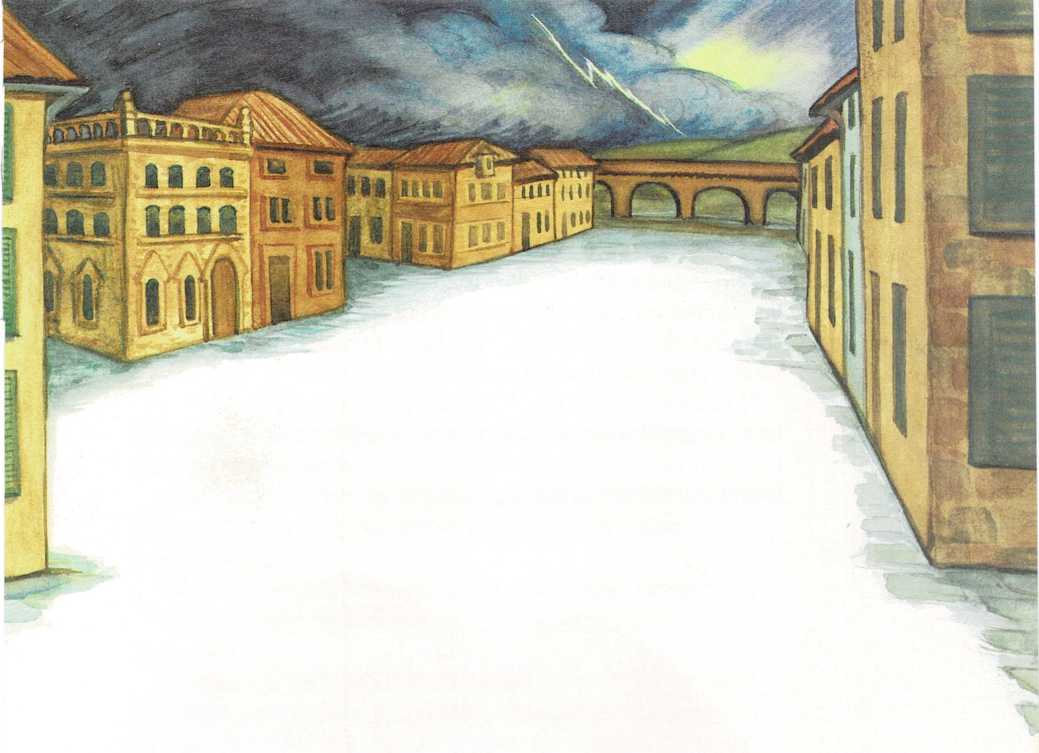

Pinocchio hated the dark street, but he was so hungry that, in spite of

it, he ran out of the house. The night was pitch-black. It thundered,

and bright flashes of lightning now and again shot across the sky,

turning it into a sea of fire. An angry wind blew cold and raised dense

clouds of dust, while the trees shook and moaned in a weird way.

Pinocchio was greatly afraid of thunder and lightning, but the hunger he

felt was far greater than his fear. In a dozen leaps and bounds, he came

to the village, tired out, puffing like a whale, and with his tongue

hanging.

The whole village was dark and deserted. The stores were closed, the

doors, the windows. In the streets, not even a dog could be seen.

Pinocchio, in desperation, ran up to a doorway, threw himself upon the

bell, and pulled it wildly, saying to himself, “Someone will surely

answer that!”

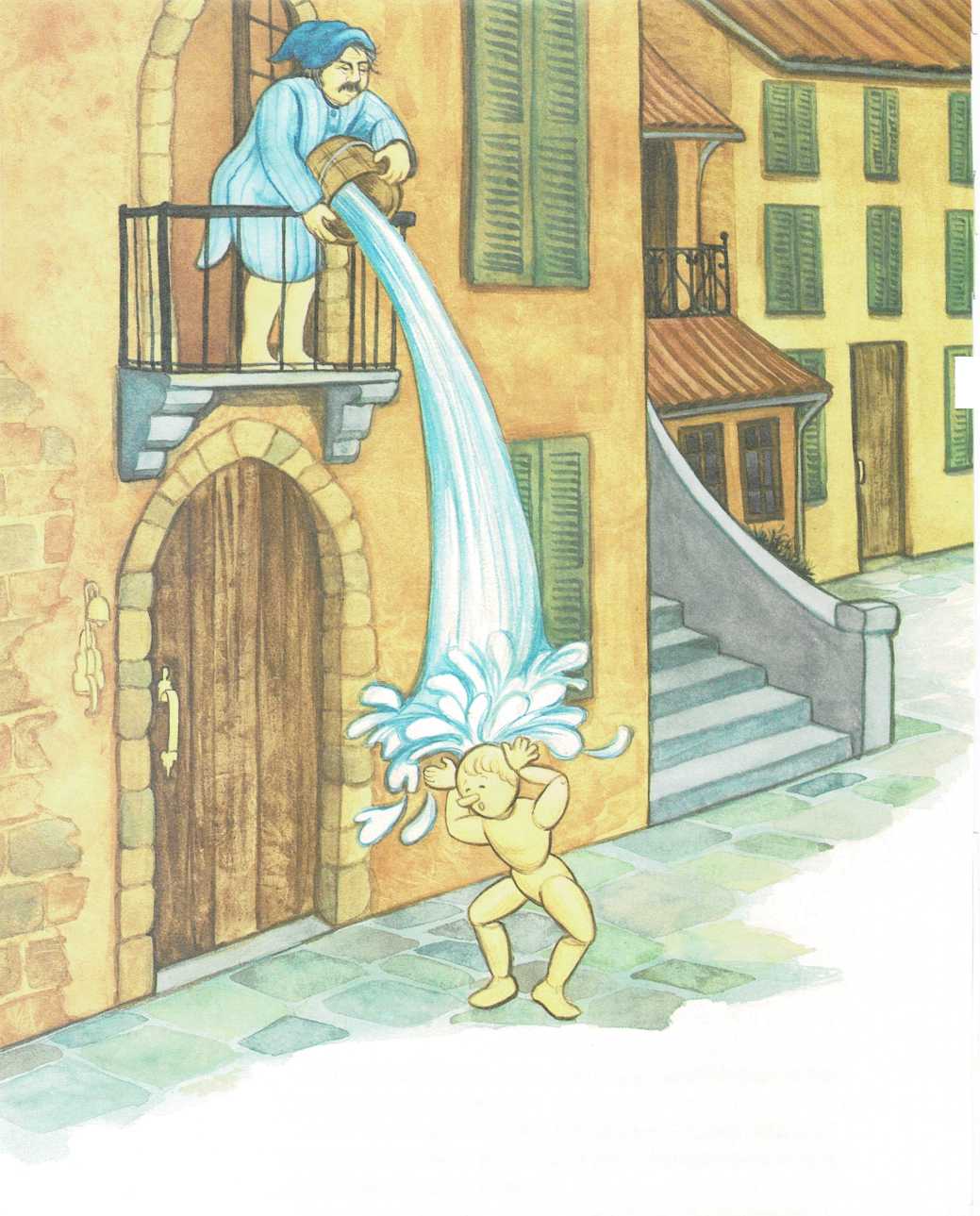

He was right. An old man in a nightcap opened the window and looked out.

He called down angrily, “What do you want at this hour of night?”

“Will you be good enough to give me a bit of bread? I am hungry.”

“Wait a minute and I’ll come right back,” answered the old fellow,

thinking he had to deal with one of those boys who love to roam around

at night ringing people’s bells while they are peacefully asleep.

After a minute or two, the same voice cried, “Get under the window and

hold out your hat!”

Pinocchio had no hat, but he managed to get under the window just in

time to feel a shower of ice-cold water pour down on his poor wooden

head, his shoulders, and over his whole body.

He returned home as wet as a rat, and tired out from weariness and

hunger.As he no longer had any strength left with which to stand, he sat down

on a little stool and put his two feet on the stove to dry them.There he fell asleep, and while he slept, his wooden

[iwi\’jd]{.underline}

feet began to burn. Slowly, very slowly, they blackened and turned to

ashes.

Pinocchio snored away happily as if his feet were not his own. At dawn

he opened his eyes just as a loud knocking sounded at the door.

“Who is it?” he called, yawning and rubbing his eyes.

“It is I,” answered a voice. It was the voice of

Geppetto.

The poor marionette, who was still half asleep, had not yet found out

that his two feet were burned and gone. As soon as he heard his father’s

voice, he jumped up from his seat to open the door, but, as he did so,

he staggered and fell headlong to the floor.

In falling, he made as much noise as a sack of wood falling from the

fifth story of a house.

“Open the door for me!” Geppetto shouted from the street.

“Father, dear Father, I can’t,” answered the marionette in despair,

crying and rolling on the floor.

“Why can’t you?”

“Because someone has eaten my feet.”

“And who has eaten them?”

“The cat,” answered Pinocchio, seeing that little animal busily playing

with some shavings in the corner of the room.

“Open! I say,” repeated Geppetto, “or I’ll give you a sound whipping

when I get in.”

“Father, believe me, I can’t stand up. Oh, dear! Oh, dear! I shall have

to walk on my knees all my life.”

Geppetto, thinking that all these tears and cries were only other pranks

of the marionette, climbed up the side of the house and went in through

the window.

At first he was very angry, but on seeing Pinocchio stretched out on the

floor and really without feet, he felt very sad and sorrowful. Picking

him up from the floor, he fondled and caressed him, talking to him while

the tears ran down his cheeks: “My little Pinocchio, my dear little

Pinocchio! How did you burn your feet?”

“I don’t know, Father, but believe me, the night has been a terrible one

and I shall remember it as long as I live. The thunder was so noisy and

the lightning so bright—and I was hungry. I put the pan on the coals,

but the chick flew away and said, Til see you again! Remember me to the

family.’ And my hunger grew, and I went out, and the old man with a

nightcap looked out of the window and threw water on me, and I came home

and put my feet on the stove to dry them because I was still hungry, and

I fell asleep and now my feet are gone but my hunger isn’t!

Oh!—Oh!—Oh!” And poor Pinocchio began to scream and cry so loudly

that he could be heard for miles around.

Geppetto, who had understood nothing of all that jumbled talk except

that the marionette was hungry, felt sorry for him and, pulling three

pears out of his pocket, offered them to him, saying, “These three pears

were for my breakfast, but I give them to you gladly. Eat them and stop

weeping.”

“If you want me to eat them, please peel them for me.”

“Peel them?” asked Geppetto, very much surprised. “I should never have

thought, dear boy of mine, that you were so dainty and fussy about your

food. Bad, very bad! In this world, even as children, we must accustom

ourselves to eat of everything, for we never know what life may hold in

store for us!”

“You may be right,” answered Pinocchio, “but I will not eat the pears if

they are not peeled. I don’t like them.”

And good old Geppetto took out a knife, peeled the three pears, and put

the skins in a row on the table.

Pinocchio ate one pear in a twinkling and started to throw the core

away, but Geppetto held his arm.

“Oh, no, don’t throw it away! Everything in this world may be of some

use!”

“But the core I will not eat!” cried Pinocchio in an angry tone.

“Who knows?” repeated Geppetto calmly.

And later the three cores were placed on the table next to the skins.

Pinocchio had eaten the three pears, or rather devoured them. Then he

yawned and wailed, “I’m still hungry.”

“But I have no more to give you.”

“Really, nothing—nothing?”

“I have only these three cores and these skins.”

“Very well, then,” said Pinocchio, “if there is nothing else I’ll eat

them.”

At first he made a wry face, but, one after another, the skins and the

cores disappeared.

“Ah! Now I feel fine!” he said after eating the last one.

“You see,” observed Geppetto, “that I was right when I told you that one

must not be too fussy and too dainty

22a about food. My dear, we never know what life may have in store for

us!”

The marionette, as soon as his hunger was appeased, started to grumble

and cry that he wanted a new pair of feet. But Mastro Geppetto, in order

to punish him for his mischief, let him alone the whole morning. After

dinner he said to him, “Why should I make your feet over again? To see

you run away from home once more?”

“I promise you,” answered the marionette, sobbing, “that from now on

I’ll be good—“

“Boys always promise that when they want something,” said Geppetto.

“I promise to go to school every day, to study, and to succeed—“

“Boys always sing that song when they want their own will.”

“But I am not like other boys! I am better than all of them and I always

tell the truth. I promise you, Father, that I’ll learn a trade, and I’ll

be the comfort and support of your old age.”

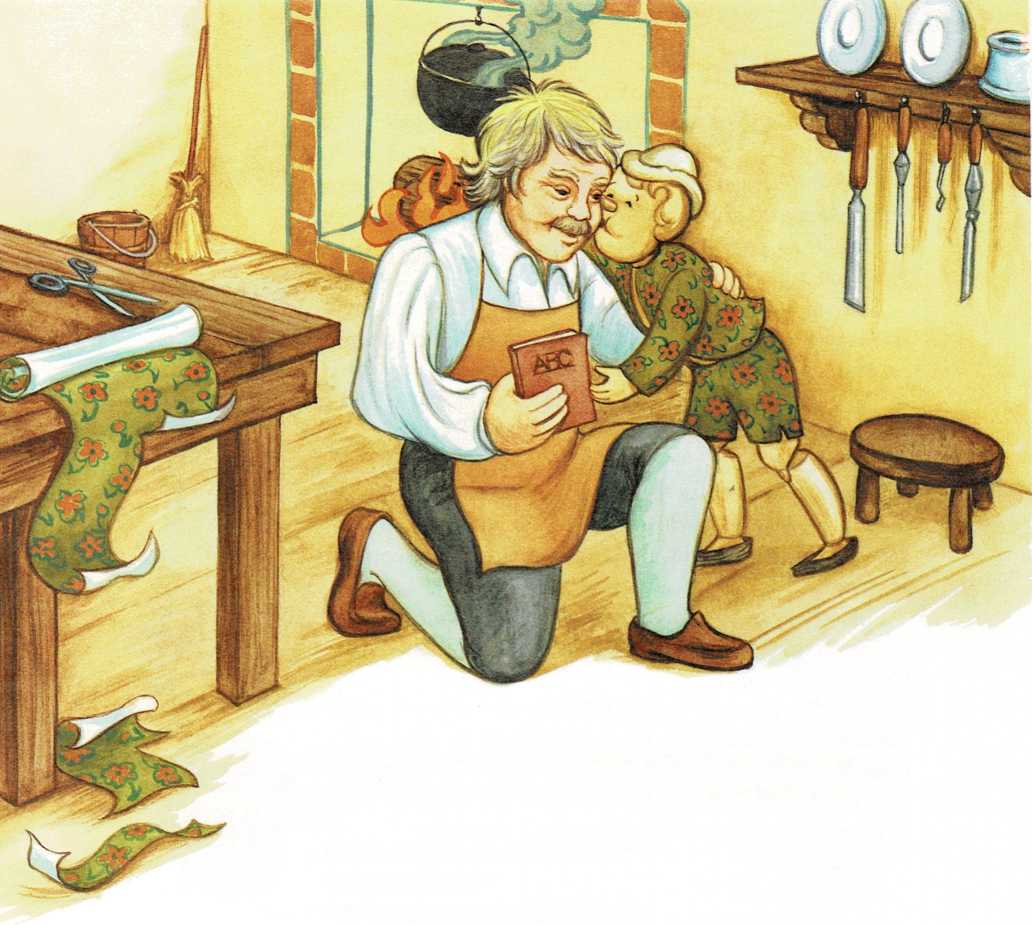

Geppetto, though trying to look very stern, felt his eyes fill with

tears and his heart soften when he saw Pinocchio so unhappy. He said no

more, but taking his tools and two pieces of wood, he set to work

diligently.

In less than an hour the feet were finished, two slender, nimble little

feet, strong and quick, modeled as if by an artist’s hands.

“Close your eyes and sleep!” Geppetto then said to the marionette.

Pinocchio closed his eyes and pretended to be asleep, while Geppetto

stuck on the two feet with a bit of glue melted in an eggshell, doing

his work so well that the joint could hardly be seen.

As soon as the marionette felt his new feet, he gave one leap from the

table and started to skip and jump around, as if he had lost his head

from very joy.

“To show you how grateful I am to you, Father, I’ll go to school now.

But to go to school I need a suit of clothes.”

Geppetto did not have a penny in his pocket, so he made his son a little

suit of flowered paper, a pair of shoes from the bark of a tree, and a

tiny cap from a bit of dough.

Pinocchio ran to look at himself in a bowl of water, and he felt so

happy that he said proudly, “Now I look like a gentleman.”

“Truly,” answered Geppetto. “But remember that fine clothes do not make

the man unless they be neat and clean.”

“Very true,” answered Pinocchio, “but, in order to go to school, I still

need something very important.”

“What is it?”

“An ABC book.”

“To be sure! But how shall we get it?”

“That’s easy. We’ll go to a bookstore and buy it.”

“And the money?”

“I have none.”

“Neither have I,” said the old man sadly.

Pinocchio, although a happy boy always, became sad and downcast at these

words. When poverty shows itself, even mischievous boys understand what

it means.

“What does it matter, after all?” cried Geppetto all at once, as he

jumped up from his chair. Putting on his old coat, full of darns and

patches, he ran out of the house without another word.

After a while he returned. In his hands he had the

ABC book for his son, but the old coat was gone. The poor fellow was in

his shirt sleeves and the day was cold.

“Where’s your coat, Father?”

“I have sold it.”

“Why did you sell your coat?”

“It was too warm.”

Pinocchio understood the answer in a twinkling, and, unable to restrain

his tears, he jumped on his father’s neck and kissed him over and over.

Pinocchio, whose nose grew longer every time he told a lie, was never

good for very long. But after many exciting adventures, which you can

read about in The Adventures of Pinocchio, he learns that a good

marionette can become a real boy. Another fine story about a wooden doll

is Hitty: Her First Hundred Years by Rachel Field.