Lamp Number 9

Tom Edison sat in his laboratory, watching an assistant light the gas

lamps. The sight always bothered him. For years he had been convinced

that electricity could be used to make light—a light as pleasant and

soft as gas light, but without the bad smell or the open flame of

burning gas.

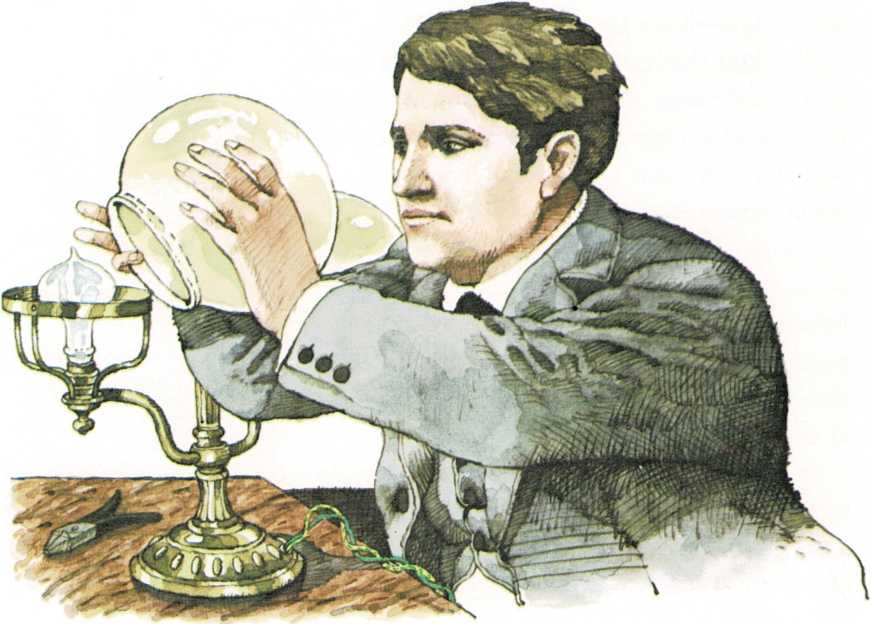

But making an electric lamp was harder than he had thought. In fact, it

was turning out to be more trouble than any invention he had ever worked

on! He was using up glass bulbs as fast as his glassblower could make

them. But no matter what shape the bulbs were, or how he arranged the

wires inside the bulb, the lights never lasted long.

One of the big problems was the filament, the thin wire that gave off

light inside the bulb. It had to be made of something that would

glow—but not burn—when electricity ran through it.

Edison had tried dozens of different filaments, including wires made of

rare metals. So far platinum seemed to work best. By winding a thin

platinum wire into a tight coil, he made a filament that would give a

bright light. And by pumping nearly all the air out of the glass bulb,

he managed to keep the filament from burning up too quickly. But the

platinum wire still got too hot. The only way to keep it from melting

was to add a

Seeing the Light

switch that turned the lamp off every few minutes.

So the platinum-wire bulb just wasn’t working. And platinum was

expensive—over five dollars an ounce. Most people couldn’t afford to

buy an expensive lamp that burned only a few hours. The bulb would have

to use a filament made from something cheaper and longer-lasting than

platinum.

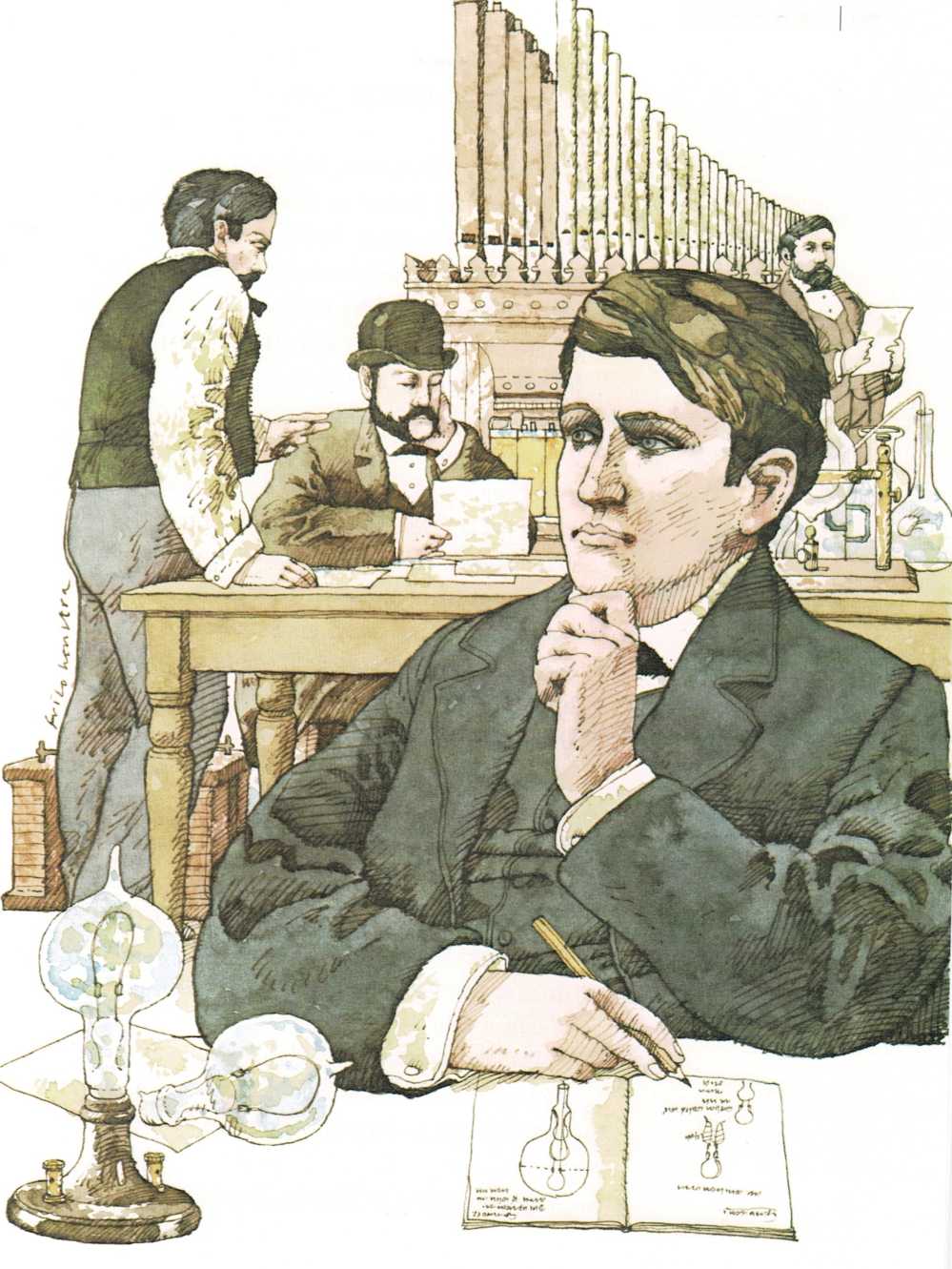

Edison began leafing back through the notebooks in which he wrote up his

experiments. Maybe some of the materials he had tried before should be

tried again. Carbon— what about carbon? A piece of carbon might work.

But carbon burned very easily. He would have to pump as much air as

possible out of the bulb, so that the carbon would glow without burning.

And the carbon would have to be very thin, like a piece of wire.

Carbon crumbled easily, too. It would be hard to make the soft, black

powder into a wire. But maybe he could mix the carbon with something

else.

Edison hunted around the laboratory until he found a small lump of tar.

He warmed the tar until it was soft, mixed in the carbon, and rolled it

into a thin \”wire.”

The carbon gave good light—but only for an hour or two. And it was

hard to make the \”wire” thin enough and strong enough at the same time.

Edison called in Charles Batchelor, an

assistant who had especially steady and skillful hands. For days he and

Batchelor rolled and squeezed mixtures of carbon and tar. But even

Batchelor broke dozens of the thin \”wires” before he could get them

rolled and mounted in the lamps.

\”There’s got to be another way,” Edison said to Batchelor, who was

carefully trying to roll another filament. \”If we could just burn a

thin piece of something to make a thread of carbon. . . . Thread! Batch,

get me a spool of thread!”

At once he and Batchelor set to work, shaping pieces of plain white

cotton thread into a hairpin curve and baking them in the laboratory

oven. While the threads were baking, Edison sent his glassblower an

order for still more of the pear- shaped bulbs they needed. Then, after

the blackened thread had cooled, Batchelor tried to fasten one of the

thin pieces of carbon into one of the new glass bulbs.

Every piece broke! Again and again Edison and Batchelor baked threads.

Eight times they managed to get a thread out of the oven and into one of

the glass bulbs. But each time the thread broke before the lamp could be

tested.

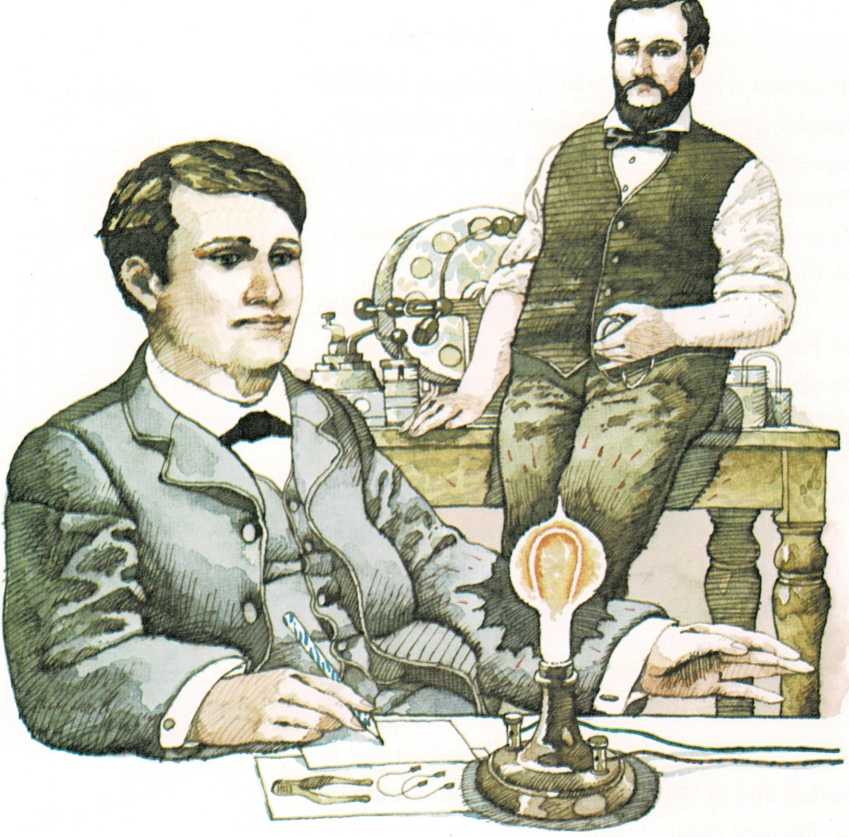

Batchelor’s steady hands grew tired. But he managed to get the carbon

thread into Lamp Number 9 without breaking it. Carefully, Edison and

Batchelor pumped the air out of the bulb. Then they turned on the

electric current and sealed the bulb.

Number 9 glowed with a soft light, like a small sun. And it kept on

glowing! Hours later the bulb was still working. Edison increased the

current. The lamp burned an hour longer before it broke. \”Then cracked

glass and busted,” Edison wrote in his notes.

There were still problems to be solved, Edison knew. But he was on the

right track—his idea had worked. Lamp Number 9 had given over half a

day of light! If it could burn that long,

Edison was sure he could make an electric light that would burn even

longer. And he had wonderful plans—plans for lighting houses,

factories, streets, and even whole cities with glowing wires in small

bulbs of glass.

Thomas Edison kept working—and he made his wonderful plans come true.

A little more than a year after Lamp Number 9 was tested, one of his

bulbs burned for 1,589 hours—over 66 days.

The light bulbs we use today have filaments made of a metal called

tungsten (TUHNG stuhn) instead of a thin carbon thread. But in other

ways they are very much like Lamp Number 9. And they are doing exactly

what Edison thought they could do—lighting houses and factories,

streets and cities all over the world!