The Peddler of Ballaghaderreen by Ruth Sawyer

Ruth Sawyer, author and storyteller, collected many folktales in

Ireland. Here is a story she heard from John Hegarty, who was a Donegal

shanachie, or travelling storyteller. Ballaghaderreen, which means \”the

road of the little oak wood,” is a town in County Roscommon, Ireland.

More years ago than you can tell me and twice as many as I can tell you,

there lived a peddler in Ballaghaderreen. He lived at the crossroads, by

himself in a bit of a cabin with one room to it, and that so small that

a man could stand in the middle of the floor and, without taking a step,

he could lift the latch on the front door, he could lift the latch on

the back door, and he could hang the kettle over the turf. That is how

small and snug it was.

Outside the cabin the peddler had a bit of a garden. In it he planted

carrots and cabbages,

onions and potatoes. In the center grew a cherry tree—as brave and

fine a tree as you would find anywhere in Ireland. Every spring it

flowered, the white blossoms covering it like a fresh falling of snow.

Every summer it bore cherries as red as heart’s blood.

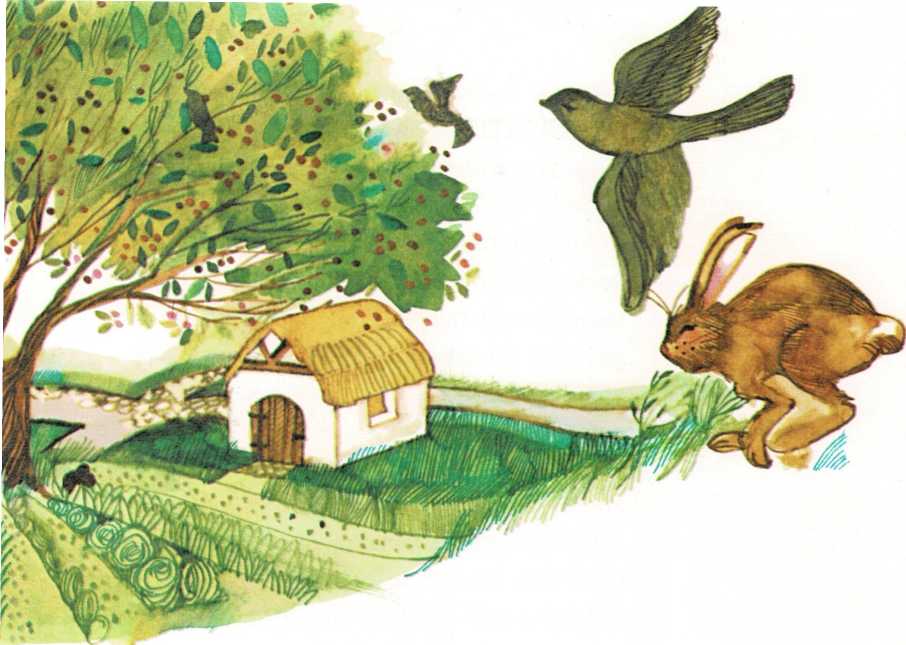

But every year, after the garden was planted the wee brown hares would

come from the copse nearby and nibble-nibble here, and nibble-nibble

there, until there was not a thing left, barely, to grow into a

full-sized vegetable that a man could harvest for his table. And every

summer as the cherries began to ripen the blackbirds came in whirling

flocks and ate the cherries as fast as they ripened.

The neighbors that lived thereabouts minded this and nodded their heads

and said:

\”Master Peddler, you’re a poor, simple man, entirely. You let the wild

creatures thieve from you without lifting your hand to stop them.”

And the peddler would always nod his head back at them and laugh and

answer: \”Nay, then, ’tis not thieving they are at all. They pay well

for what they take. Look you—on yonder cherry tree the blackbirds sing

sweeter nor they sing on any cherry tree in Ballaghaderreen. And the

brown hares make good company at dusk-hour for a lonely man.”

In the country roundabout, every day when there was market, a wedding,

or a fair, the peddler would be off at ring-o’-day, his pack strapped on

his back, one foot ahead of the other, fetching him along the road. And

when he reached the town diamond he would open his pack, spread it on

the green turf, and, making a hollow of his two hands, he would call:

\”Come buy a trinket—come buy a brooch—

Come buy a kerchief of scarlet or yellow!”

In no time at all there would be a great crowding of lads and lasses and

children about him, searching his pack for what they might be wanting.

And like as not, some barefooted lad would hold up a jackknife and ask:

\”How much for this, Master Peddler?”

And the peddler would answer: \”Half a crown.”

And the lad would put it back, shaking his

head dolefully. \”Faith, I haven’t the half of that, nor likely ever to

have it.”

And the peddler would pull the lad over to him and whisper in his ear:

\”Take the knife—’twill rest a deal more easy in your pocket than in

my pack.”

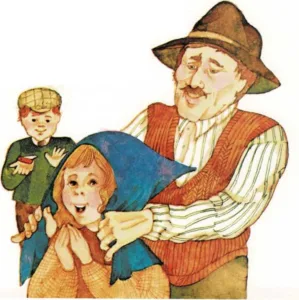

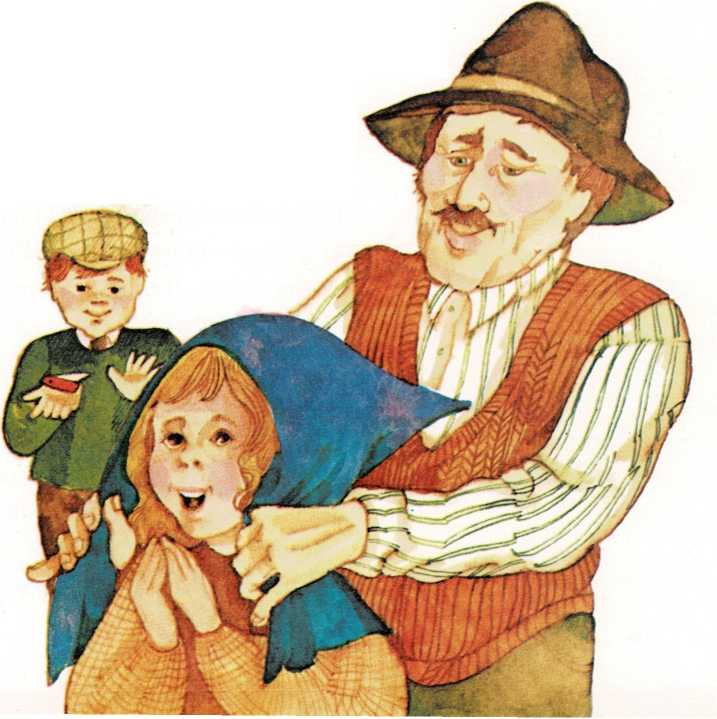

Then, like as not, some lass would hold up a blue kerchief to her yellow

curls and ask: \”Master Peddler, what is the price of this?”

And the peddler would answer: \”One shilling sixpence.”

And the lass would put it back, the smile gone from her face, and she

turning away.

And the peddler would catch up the kerchief again and tie it himself

about her curls and laugh and say: \”Faith, there it looks far prettier

than ever it looks in my pack. Take it, with God’s blessing.”

So it would go—a brooch to this one and a top to that. There were days

when the peddler

took in little more than a few farthings. But after those days he would

sing his way homeward; and the shrewd ones would watch him passing by

and wag their fingers at him and say: \”You’re a poor, simple man,

Master Peddler. You’ll never be putting a penny by for your old age.

You’ll end your days like the blackbirds, whistling for crumbs at our

back doors. Why, even the vagabond dogs know they can wheedle the half

of the bread you are carrying in your pouch, you’re that simple.”

Which likewise was true. Every stray, hungry dog knew him the length and

breadth of the county. Rarely did he follow a road without one tagging

his heels, sure of a noonday sharing of bread and cheese.

There were days when he went abroad without his pack, when there was no

market day, no wedding or fair. These he spent with the children, who

would have followed him about like the dogs, had their mothers let them.

On these days he would sit himself down on some doorstep and when a

crowd of children had gathered he would tell them tales—old tales of

Ireland—tales of the good folk, of the heroes, of the saints. He knew

them all, and he knew how to tell them, the way the children would never

be forgetting one of them, but carry them in their hearts until they

were old.

And whenever he finished a tale he would say, like as not, laughing and

pinching the cheek of some wee lass: \”Mind well your manners, whether

you are at home or abroad, for you can never be telling what good folk,

or saint,

or hero you may be fetching up with on the road—or who may come

knocking at your doors. Aye, when Duirmuid, or Fionn or Oisin or Saint

Patrick walked the earth they were poor and simple and plain men; it

took death to put a grand memory on them. And the poor and the simple

and the old today may be heroes tomorrow—you never can be telling. So

keep a kind word for all, and a gentling hand.”

Often an older would stop to listen to the scraps of words he was

saying; and often as not he would go his way, wagging his finger and

mumbling: “The poor, simple man. He’s as foolish as the blackbirds.”

Spring followed winter in Ireland, and summer followed close upon the

heels of both. And winter came again and the peddler grew old. His pack

grew lighter and lighter, until the neighbors could hear the trinkets

jangling inside as he passed, so few things were left. They would nod

their heads and say to one another: “Like as not his pockets are as

empty as his pack. Time will come, with winter at hand, when he will be

at our back doors begging crumbs, along with the blackbirds.”

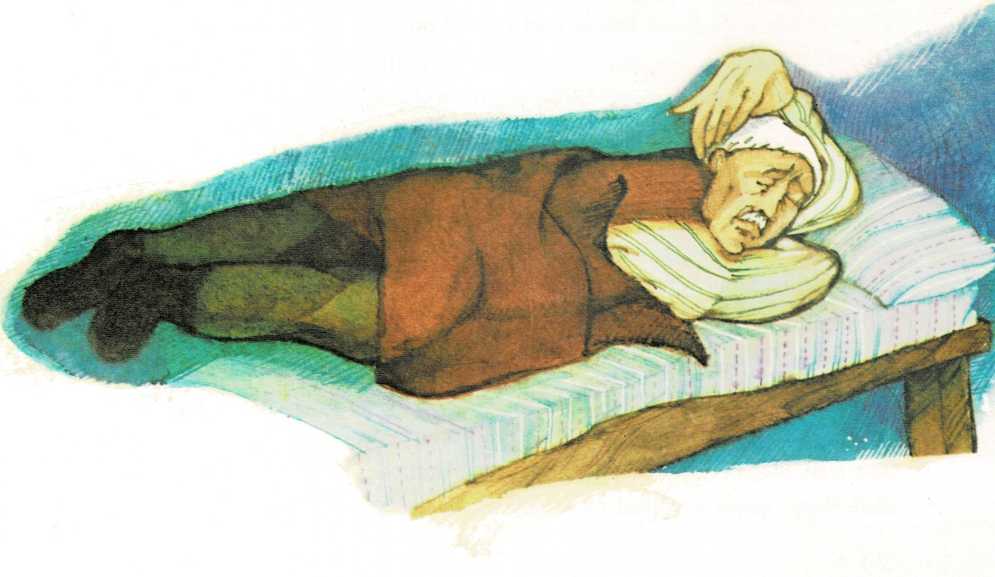

The time did come, as the neighbors had prophesied it would, smug and

proper, when the peddler’s pack was empty, when he had naught in his

pockets and naught in his cupboard. That night he went hungry to bed.

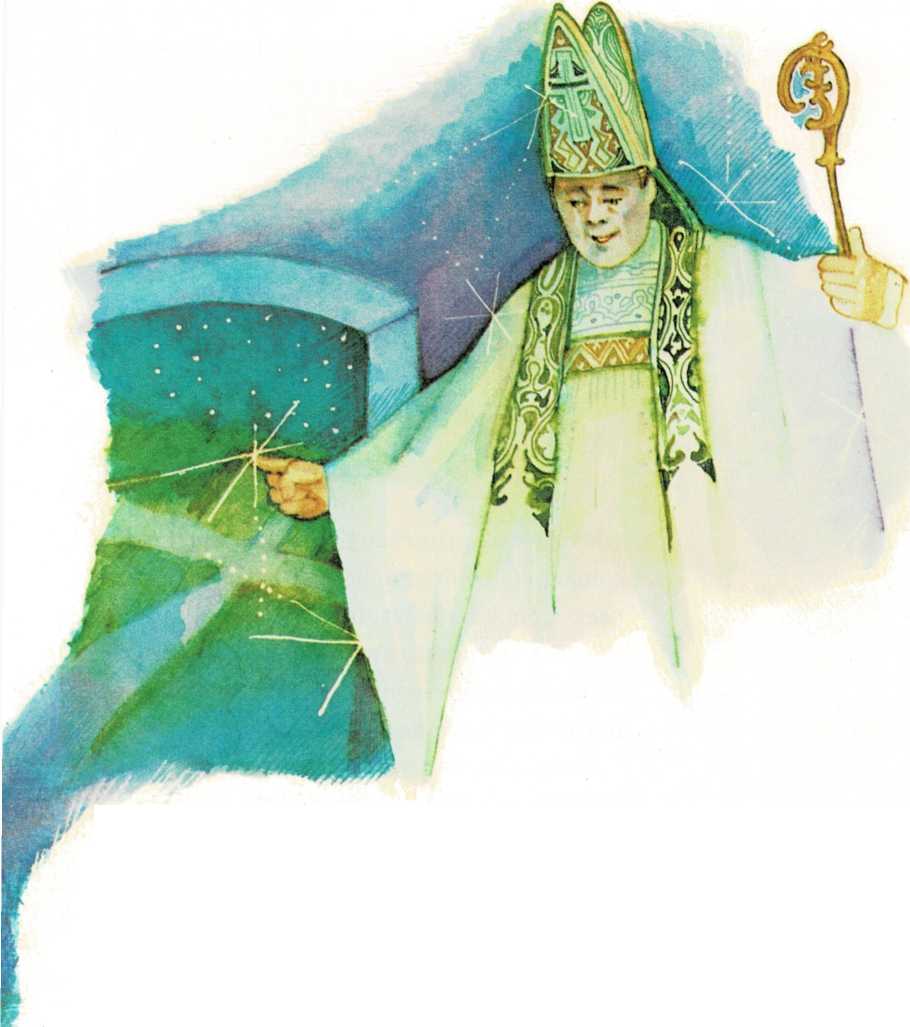

Now it is more than likely that hungry men will dream; and the peddler

of Ballaghaderreen had a strange dream that night. He dreamed that there

came a sound of knocking in the

middle of the night. Then the latch on the front door lifted, the door

opened without a creak or a cringe, and inside the cabin stepped Saint

Patrick. Standing in the doorway the good man pointed a finger; and he

spoke in a voice tuned as low as the wind over the bogs. \”Peddler,

peddler of Ballaghaderreen, take the road to Dublin Town. When you get

to the bridge that spans the Liffey you will hear what you were meant to

hear.”

On the morrow the peddler awoke and remembered the dream. He rubbed his

stomach and found it mortal empty; he stood on his legs and found them

trembling in under him; and he said to himself: \”Faith, an empty

stomach and weak legs are the worst traveling companions a man can have,

and Dublin is a long way. Fil bide where I am.”

That night the peddler went hungrier to bed, and again came the dream.

There came the

knocking on the door, the lifting of the latch. The door opened and

Saint Patrick stood there, pointing the road: \”Peddler, peddler of

Ballaghaderreen, take the road that leads to Dublin Town. When you get

to the bridge that spans the Liffey you will hear what you were meant to

hear!”

The second day it was the same as the first. The peddler felt the hunger

and the weakness stronger in him, and stayed where he was. But

when he woke after the third night and the third coming of the dream, he

rose and strapped his pack from long habit upon his back and took the

road to Dublin. For three long weary days he traveled, barely staying

his fast, and on the fourth day he came into the city.

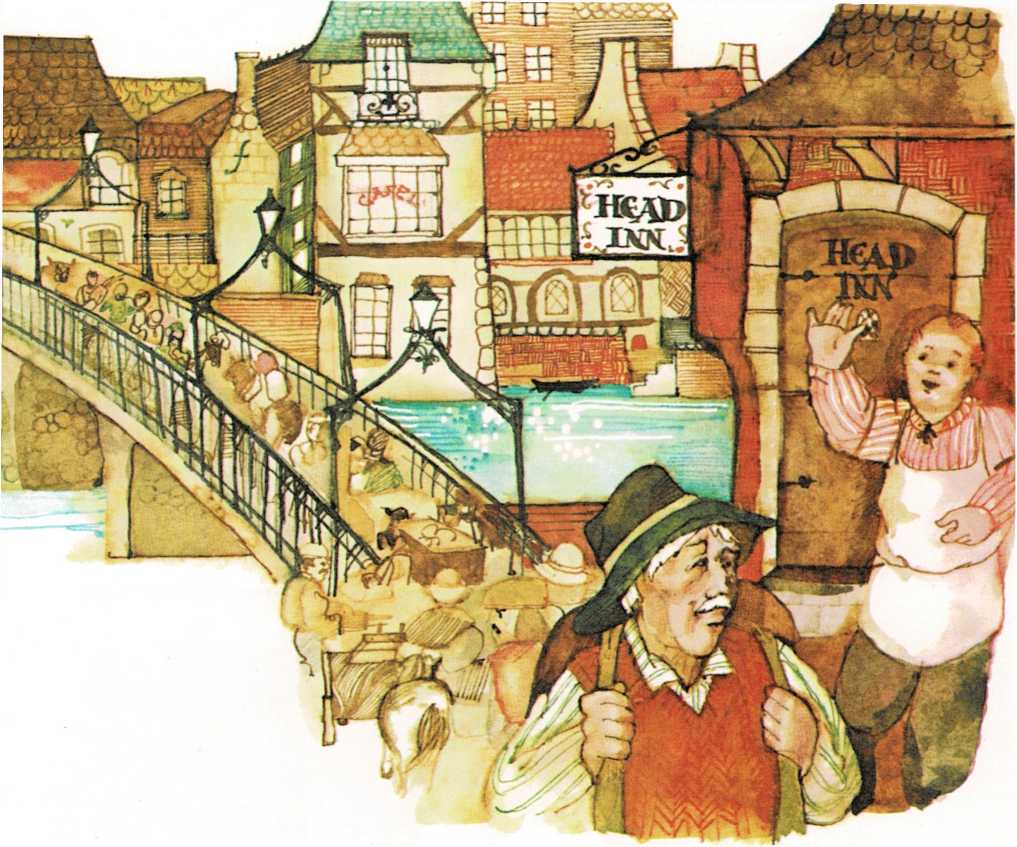

Early in the day he found the bridge spanning the river and all the

lee-long day he stood there, changing his weight from one foot to the

other, shifting his pack to ease the drag of it, scanning the faces of

all who passed by. But although a great tide of people swept this way,

and a great tide swept that, no one stopped and spoke to him.

At the end of the day he said to himself: \”I’ll find me a blind alley,

and like an old dog I’ll lay me down in it and die.” Slowly he moved off

the bridge. As he passed by the Head Inn of Dublin, the door opened and

out came the landlord.

To the peddler’s astonishment he crossed the thoroughfare and hurried

after him. He clapped a strong hand on his shoulder and cried: \”Arra,

man hold a minute! All day I’ve been watching you. All day I have seen

you standing on the bridge like an old rook with rent wings. And of all

the people passing from the west to the east, and of all the people

passing from the east to the west, not one crossing the bridge spoke

aught with you. Now I am filled with a great curiosity entirely to know

what fetched you here.”

Seeing hunger and weariness on the peddler, he drew him toward the inn.

\”Come; in return for having my curiosity satisfied you shall have rest

in the kitchen yonder, with bread and cheese and ale. Come.”

So the peddler rested his bones by the kitchen hearth and he ate as he

hadn\’t eaten in many days. He was satisfied at long last and the

landlord repeated his question. \”Peddler, what fetched you here?”

\”For three nights running I had a dream—” began the peddler, but he

got no further.

The landlord of the Head Inn threw back his head and laughed. How he

laughed, rocking on his feet, shaking the whole length of him!

\”A dream you had, by my soul, a dream!” He spoke when he could get his

breath. \”I could be telling you were the cut of a man to have

dreams, and to listen to them, what’s more. Rags on your back and hunger

in your cheeks and age upon you, and I’ll wager not a farthing in your

pouch. Well, God’s blessing on you and your dreams.”

The peddler got to his feet, saddled his pack, and made for the door. He

had one foot over the sill when the landlord hurried after him and again

clapped a hand on his shoulder.

\”Hold, Master Peddler,” he said, \”I too had a dream, three nights

running.” He burst into laughter again, remembering it. \”I dreamed

there came a knocking on this very door, and the latch lifted, and,

standing in the doorway, as you are standing, I saw Saint Patrick. He

pointed with one finger to the road running westward and he said:

\’Landlord, Landlord of the Head Inn, take that road to

Ballaghaderreen. When you come to the crossroads you will find a wee

cabin, and beside the cabin a wee garden, and in the center of the

garden a cherry tree. Dig deep under the tree and you will find

gold—much gold.’ “

The landlord paused and drew his sleeve across his mouth to hush his

laughter.

\”Ballaghaderreen! I never heard of the place. Gold under a cherry

tree—whoever heard of gold under a cherry tree! There is only one

dream that I hear, waking or sleeping, and it’s the dream of gold, much

gold, in my own pocket. Aye, listen, ’tis a good dream.” And the

landlord thrust a hand into his pouch and jangled the coins loudly in

the peddler’s ear.

Back to Ballaghaderreen went the peddler, one foot ahead of the other.

How he got there I cannot be telling you. He unslung his pack, took up a

mattock lying nearby, and dug under the cherry tree. He dug deep and

felt at last the scraping of the mattock against something hard and

smooth. It took him time to uncover it and he found it to be an old sea

chest, of foreign pattern and workmanship, bound around with bands of

brass. These he broke, and lifting the lid he found the chest full of

gold, tarnished

and clotted with mold; pieces of six and pieces of eight and Spanish

doubloons.

I cannot begin to tell the half of the goodness that the peddler put

into the spending of that gold. But this I know. He built a chapel at

the crossroads—a resting place for all weary travelers journeying

thither.

And after he had gone the neighbors had a statue made of him and placed

it facing the crossroads. And there he stands to this day, a pack on his

back and a dog at his heels.