Independence Day

by Laura Ingalls Wilder

In this story, taken from the book Farmer Boy, young Almanzo Wilder

enjoys the Fourth of July as it was celebrated in northern New York more

than a hundred years ago. Almanzo also learns how much fifty cents is

really worth.

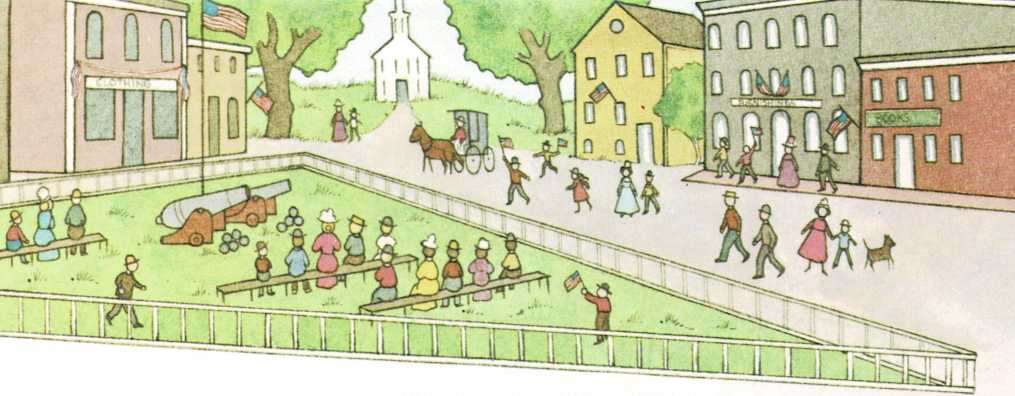

The Square was not really square. The railroad made it three-cornered.

But everybody called it the Square, anyway. It was fenced, and grass

grew there. Benches stood in rows on the grass, and people were filing

between the benches and sitting down as they did in church.

Almanzo went with Father to one of the best front seats. All the

important men stopped to shake hands with Father. The crowd kept coming

till all the seats were full, and still there were people outside the

fence.

The band stopped playing, and the minister prayed. Then the band tuned

up again and everybody rose. Men and boys took off their hats. The band

played, and everybody sang.

Oh! say, can you see, by the dawn’s early light, What so proudly we

hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming?

Whose broad stripes and bright stars, thro’ the perilous fight,

O’er the ramparts we watched were so gallantly streaming?

From the top of the flagpole, up against the blue sky, the Stars and

Stripes were fluttering. Everybody looked at the American flag, and

Almanzo sang with all his might.

Then everyone sat down, and a Congressman stood up on the platform.

Slowly and solemnly he read the Declaration of Independence.

\”When in the course of human events it becomes necessary for one people

… to assume among the powers of the earth the separate and equal

station. … We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are

created equal. . . .”

Almanzo felt solemn and very proud.

Then two men made long political speeches. One believed in high tariffs,

and one believed in free trade. All the grown-ups listened hard, but

Almanzo did not understand the speeches very well and he began to be

hungry. He was glad when the band played again.

The music was so gay; the bandsmen in their blue and red and their brass

buttons tootled merrily, and the fat drummer beat rat-a-tat-tat on the

drum. All the flags were fluttering and everybody was happy, because

they were free

and independent and this was Independence Day. And it was time to eat

dinner.

Almanzo helped Father feed the horses while Mother and the girls spread

the picnic lunch on the grass in the churchyard. Many others were

picnicking there, too, and after he had eaten all he could Almanzo went

back to the Square.

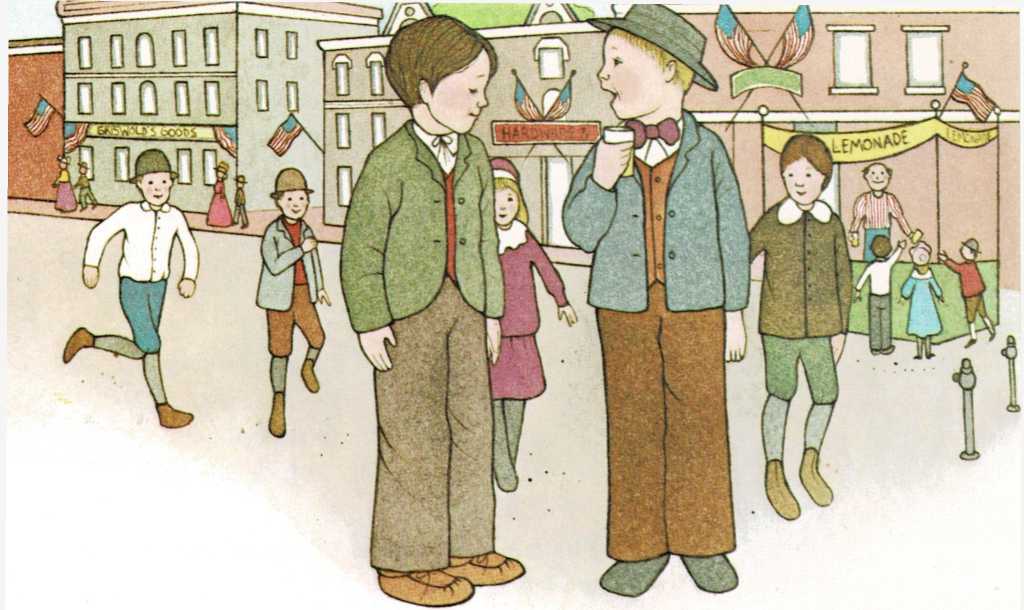

There was a lemonade-stand by the hitching- posts. A man sold pink

lemonade, a nickel a glass, and a crowd of the town boys were standing

around him. Cousin Frank was there. Almanzo had a drink at the town

pump, but Frank said he was going to buy lemonade. He had a nickel. He

walked up to the stand and bought a glass of the pink lemonade and drank

it slowly. He smacked his lips and rubbed his stomach and said:

\”Mmmm! Why don’t you buy some?”

\”Where’d you get the nickel?” Almanzo asked. He had never had a nickel.

Father gave him a penny every Sunday to put in the collection-box in

church; he had never had any other money.

\”My father gave it to me,” Frank bragged. \”My father gives me a nickel

every time I ask him.”

\”Well, so would my father if I asked him,” said Almanzo.

\”Well, why don’t you ask him?” Frank did not believe that Father would

give Almanzo a nickel. Almanzo did not know whether Father would, or

not.

\”Because I don’t want to,” he said.

\”He wouldn’t give you a nickel,” Frank said.

\”He would, too.”

\”I dare you to ask him,” Frank said. The other boys were listening.

Almanzo put his hands in his pockets and said:

\”I’d just as lief ask him if I wanted to.”

\”Yah, you’re scared!” Frank jeered. \”Double dare! Double dare!”

Father was a little way down the street, talking to Mr. Paddock, the

wagon-maker. Almanzo walked slowly toward them. He was faint-hearted,

but he had to go. The nearer he got to Father, the more he dreaded

asking for a nickel. He had never before thought of doing such a thing.

He was sure Father would not give it to him.

He waited till Father stopped talking and looked at him.

\”What is it, son?” Father asked.

Almanzo was scared. \”Father,” he said.

\”Well, son?”

\”Father,” Almanzo said, \”would you—would you give me—a nickel?”

He stood there while Father and Mr. Paddock looked at him, and he wished

he could get away. Finally Father asked:

\”What for?”

Almanzo looked down at his moccasins and muttered:

\”Frank had a nickel. He bought pink lemonade.”

\”Well,” Father said, slowly, \”if Frank treated you, it’s only right

you should treat him.” Father put his hand in his pocket. Then he

stopped and asked:

\”Did Frank treat you to lemonade?” Almanzo wanted so badly to get the

nickel that he nodded. Then he squirmed and said:

\”No, Father.”

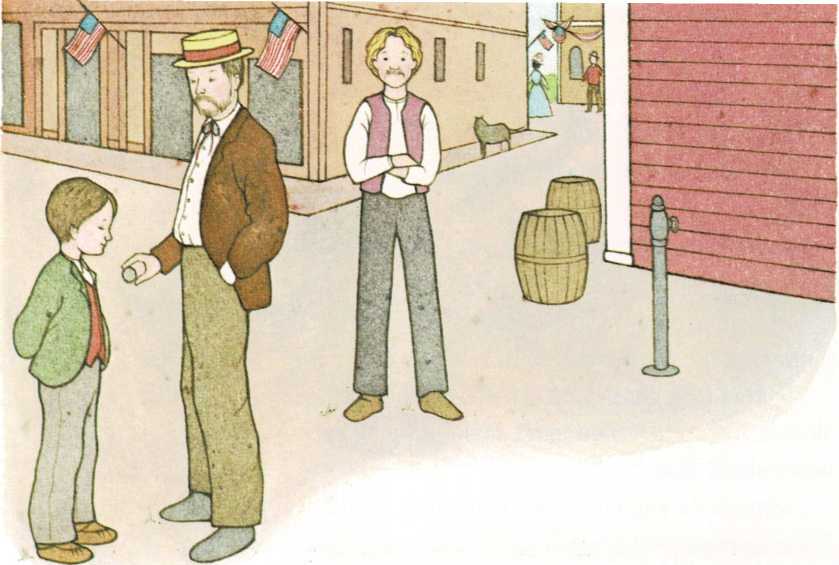

Father looked at him a long time. Then he took out his wallet and opened

it, and slowly he took out a round, big silver half-dollar. He asked:

\”Almanzo, do you know what this is?”

\”Half a dollar,” Almanzo answered.

\”Yes. But do you know what half a dollar is?”

Almanzo didn’t know it was anything but half a dollar.

\”It’s work, son,” Father said. \”That’s what money is; it’s hard work.”

Mr. Paddock chuckled. \”The boy’s too young, Wilder,” he said. \”You

can’t make a youngster understand that.”

\”Almanzo’s smarter than you think,” said Father.

Almanzo didn’t understand at all. He wished he could get away. But Mr.

Paddock was looking at Father just as Frank looked at Almanzo when he

double-dared him, and Father had said Almanzo was smart, so Almanzo

tried to look like a smart boy. Father asked:

\”You know how to raise potatoes, Almanzo?”

\”Yes,” Almanzo said.

\”Say you have a seed potato in the spring, what do you do with it?”

\”You cut it up,” Almanzo said.

\”Go on, son.”

\”Then you harrow—first you manure the field, and plow it. Then you

harrow, and mark the ground. And plant the potatoes, and plow them, and

hoe them. You plow and hoe them twice.”

\”That’s right, son. And then?”

\”Then you dig them and put them down cellar.”

\”Yes. Then you pick them over all winter;

you throw out all the little ones and the rotten ones. Come spring, you

load them up and haul them here to Malone, and you sell them. And if you

get a good price, son, how much do you get to show for all that work?

How much do you get for half a bushel of potatoes?”

\”Half a dollar,” Almanzo said.

\”Yes,” said Father. \”That’s what’s in this half-dollar, Almanzo. The

work that raised half a bushel of potatoes is in it.”

Almanzo looked at the round piece of money that Father held up. It

looked small, compared with all that work.

\”You can have it, Almanzo,” Father said. Almanzo could hardly believe

his ears. Father gave him the heavy half-dollar.

\”It’s yours,” said Father. \”You could buy a sucking pig with it, if

you want to. You could raise it, and it would raise a litter of pigs,

worth four, five dollars apiece. Or you can trade that half-dollar for

lemonade, and drink it up. You do as you want, it’s your money.”

Almanzo forgot to say thank you. He held the half-dollar a minute, then

he put his hand in his pocket and went back to the boys by the

lemonade-stand. The man was calling out,

\”Step this way, step this way! Ice-cold lemonade, pink lemonade, only

five cents a glass! Only half a dime, ice-cold pink lemonade! The

twentieth part of a dollar!”

Frank asked Almanzo:

\”Where’s the nickel?”

\”He didn’t give me a nickel,” said Almanzo, and Frank yelled:

\”Yah, yah! I told you he wouldn’t! I told you so!”

\”He gave me half a dollar,” said Almanzo.

The boys wouldn’t believe it till he showed them. Then they crowded

around, waiting for him to spend it. He showed it to them all, and put

it back in his pocket.

\”I’m going to look around,” he said, \”and buy me a good little sucking

pig.”

The band came marching down the street, and they all ran along beside

it. The flag was gloriously waving in front, then came the buglers

blowing and the fifers tootling and the drummer rattling the drumsticks

on the drum. Up the street and down the street went the band, with all

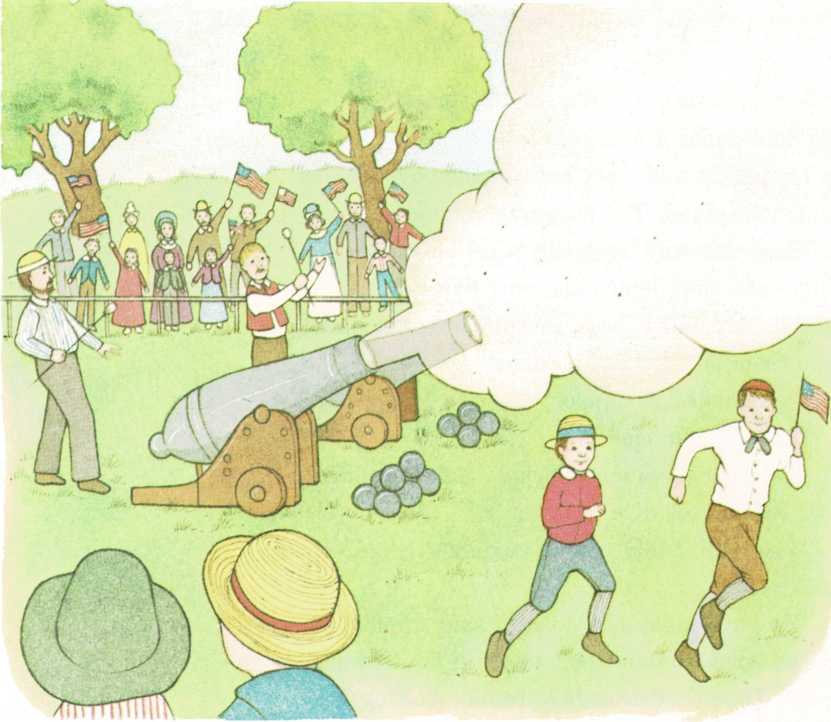

the boys following it, and then it stopped in the Square by the brass

cannons.

Hundreds of people were there, crowding to watch.

The cannons sat on their haunches, pointing their long barrels upward.

The band kept on playing. Two men kept shouting, \”Stand back!

Stand back!” and other men were pouring black powder into the cannons’

muzzles and pushing it down with wads of cloth on long rods.

The iron rods had two handles, and two men pushed and pulled on them,

driving the black powder down the brass barrels. Then all the boys ran

to pull grass and weeds along the railroad tracks. They carried them by

armfuls to the cannons, and the men crowded the weeds into the cannons.’

muzzles and drove them down with the long rods.

A bonfire was burning by the railroad tracks, and long iron rods were

heating in it.

When all the weeds and grass had been packed tight against the powder in

the cannons, a man took a little more powder in his hand and carefully

filled the two little touchholes in the barrels. Now everybody was

shouting, \”Stand back! Stand back!\”

Mother took hold of Almanzo’s arm and made him come away with her. He

told her:

\”Aw, Mother, they’re only loaded with powder and weeds. I won’t get

hurt, Mother. I’ll be careful, honest.” But she made him come away from

the cannons.

Two men took the long iron rods from the fire. Everybody was still,

watching. Standing as far behind the cannons as they could, the two men

stretched out the rods and touched their red-hot tips to the touchholes.

A little flame like a candle-flame flickered up from the powder. The

little flames stood there burning; nobody breathed. Then—BOOM!

The cannons leaped backward, the air was full of flying grass and weeds.

Almanzo ran with all the other boys to feel the warm muzzles of the

cannons. Everybody was exclaiming about what a loud noise they had made.

\”That’s the noise that made the Redcoats run!” Mr. Paddock said to

Father.

\”Maybe,” Father said, tugging his beard. \”But it was muskets that won

the Revolution. And don’t forget it was axes and plows that made this

country.”

\”That’s so, come to think of it,” Mr. Paddock said.

Independence Day was over. The cannons had been fired, and there was

nothing more to do but hitch up the horses and drive home to do the

chores.

If you enjoyed this story, you will want to read the rest of Farmer

Boy, as well as all the other books in the \”Little House” series.