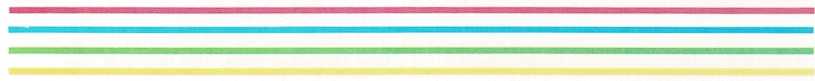

The preteen and “the gang”

Ever since children entered school, they have been learning that the

group is something to be reckoned with. Always, part of their concern

was to be accepted according to the group standards set by the

neighborhood play group or their schoolmates. In the pre teen period,

however, what was perhaps a marginal problem suddenly becomes an

essential adjustment.

The most important part of the world used to be the family. Suddenly,

the “kid

During the preteen period, the gang may become more important than

the family.

culture” of the neighborhood takes over. Now the important thing in the

children’s lives is to be in line with the code of their peers, even at

the cost of considerable open conflict with their families.

Characteristics of group leaders take on extra significance in the lives

of preteens.

Parents become “The Adults”

Many parents report that what hurts most during the preteen period is

the peculiar way in which preteens cut off whatever relationships have

existed between them and their parents by suddenly making their parents

“The Adults.” You know that they know better, that they love you,

but—especially in public—they treat even your fair demands as angry

insults from an enemy. In fact, once your child has shifted you from the

role of parent to the role of “The Adult,” nothing personal may remain.

You may become two power agents in battle.

You may happily suggest to your daughter that she have some of her

friends over for a party. Her comment: “Where will you be?” You stammer

something about being somewhere in the house and assure your offspring

that you will not intrude on her fun. You get the rejoinder,”But we

don’t want any Adults around.” It is hard to accept the fact that to

your own child you are suddenly an archenemy. Of course, you should take

consolation in the fact that not all preteens react so dramatically.

Your child’s attitude is normal. In fact, the more youngsters are

“attached” to a

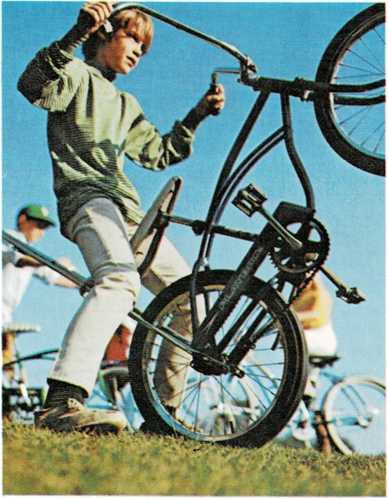

Experimenting with lipstick is normal for a preteen girl but may

cause conflict with parents.

parent, the heavier is their need to defend against the parent—or the

attachment to the parent. It is often the very loving and beloved

parent, the very cordial teacher, who bears the brunt of this puzzling

behavior. And although it is easier to understand than to bear, it

should not be taken personally. The battle stance between the preteens

and parents or teachers as “the authorities to be challenged” does not

mean that the relationships deteriorate permanently. It only means that,

in certain moments of their lives, children perceive themselves as

members of the preteens. And that leaves parents and teachers in the

role of “The Adults.”

Most preteens experience such moments frequently. There is no reason for

concern unless the experiences become so all-inclusive that no personal

relationship remains between parent and child.

Secrecy

Another way the preteen may try to cut you out of things is to have

secrets. Girls, especially, may tease you by mentioning something

somebody said or did, and then clam up if you want details. The

youngster who previously ran to you with every little concern now cuts

you off. Inquiries about what happened at school are met with a curt

“Nothing.”

This secrecy has reasons, though, and is part of the normal preteen

trend. Partly, it is the preteen’s need to have a domain safe from adult

invasion. The content of a secret may be irrelevant. It is the fact of

having one that counts.

Even some of the preteens’ need to collect things and keep the things in

their pockets or dresser drawers is part of that need to have their own

domain. For example, if parents try to get the preteen’s stamp or coin

collection transformed into a well-organized enterprise, parents may

find that the child loses interest in the hobby. The hobby has become

family domain instead of something for the child alone to deal with.

Related to the need for secrets is the fact that at this age

communication often comes easier with other adults than with parents.

This does not mean that your child has lost confidence in you. It is

simply typical.

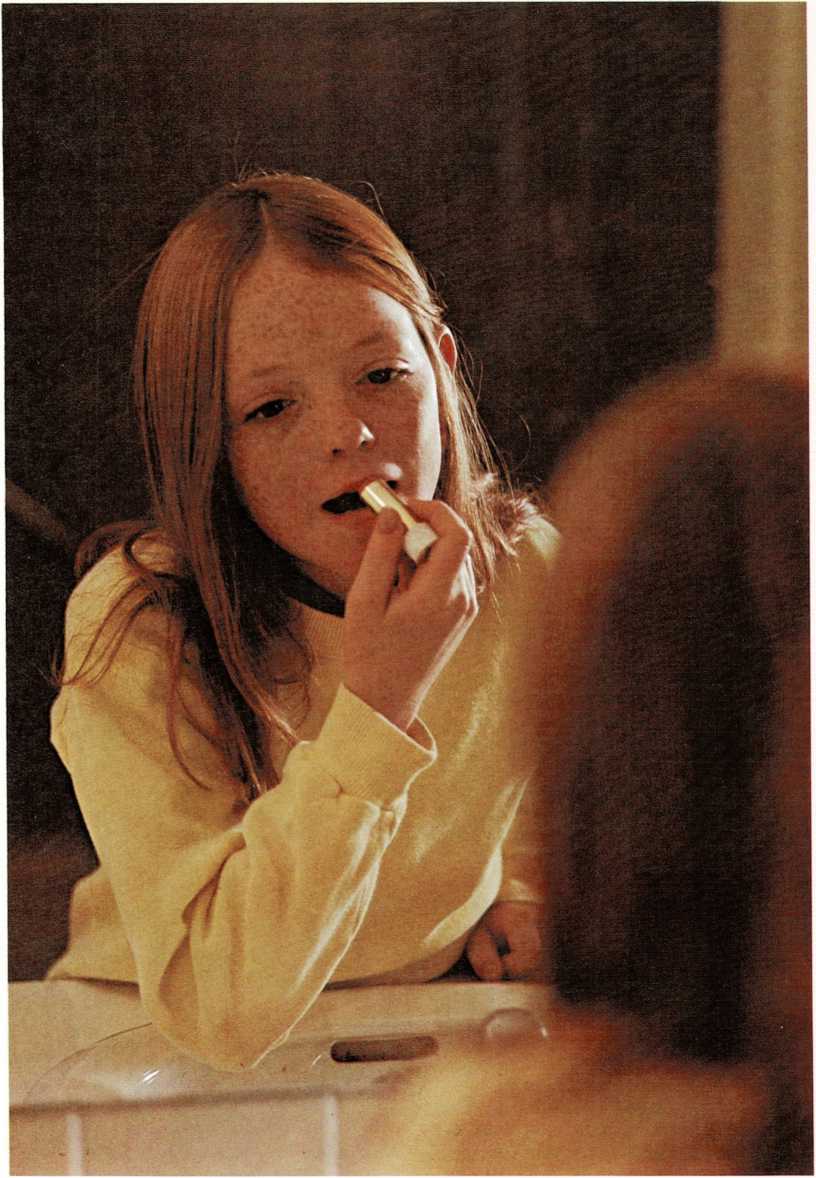

Picking up the dare

During the preteens and teens, even the most wonderful youngster may

become extremely vulnerable to the compelling illogic of a dare. Under

certain conditions a pre- teen must pick up a dare, no matter how silly,

dangerous, disgusting, or obnoxious it is. A child who does not pick up

a dare loses honor in the eyes of the group.

Picking up the dare is seen most clearly in the older teen-ager. In the

preteen years, the kind of dare children are exposed to is not so easy

to recognize, but plays as heavy a role. A preteen may, for example,

accept a dare to put thumbtacks on the teacher’s chair, talk dirty in

public, thumb the nose at an adult, or talk back to an adult.

Dare situations may develop even when the gang is not around.

Psychologically, preteens may feel that the gang is looking over their

shoulders. If the way parents scold preteens or demand compliance seems

to constitute an unwritten dare, the youngster may suddenly become

silly, stubborn, fresh, or defiant. They then become actors in a show

put on for the benefit of the absent group. They have to accept the dare

or

Preteens must pick up a dare. If they do not, they lose honor in the

eyes of the gang.

they will violate the code that governs their actions.

In dealing with a dare, avoid “extraneous reasoning.” Do not resort to,

“Your cousin Janice doesn’t wear lipstick,” or “When I was your age, I

never would have done that.”

Fortunately, only a few situations at a time become loaded with this

dare-vulnerability. In all other areas the child remains as reasonable,

or at least as easy to influence, as before. For one youngster, being

asked to wear warm underwear or put on boots and mittens may be an

unbearable demand; for another, an anxious admonition not to climb a

tree or talk back to a teacher is an unbearable challenge. For another,

a parent’s concern about lipstick, table manners, or language may be it.

And what is “it” changes from time to time.

These dares, although changeable, are fairly easy to identify. A more

important concern, and one that is not easy to satisfy, is just what

constitutes a dare when your preteen is alone with the gang. If the

child shows signs of disturbing behavior, or is having unusual trouble

at school, you will want to know if it is in response to a dare or if a

basic problem is involved. Your child’s teacher or school counselor may

help you answer this difficult question.

If your youngster is heavily dependent on what you consider the bad

standards of the group, the worst thing you can do is preach against

them. This is considered an additional dare for the child to show

loyalty to those friends, in spite of knowing better and being sure that

you are right. Strengthening your child’s own judgment and awareness is

the only safe way to help, but this is a longtime job. Remember that

success is not achieved overnight.

Face-saving

Many minor issues of daily life, such as schedules or parents’

suggestions about what clothing to wear, may put children into a

situation in which they are afraid of surrendering too openly to adult

demands. Immediate and easy acceptance of adult orders somehow reminds

preteens too much of early childhood years. Even though they

realize that their parents’ demands are perfectly reasonable, they still

have to fight before surrendering. It is honorable to surrender after

battle, but simply giving in is cowardly and childish. This has nothing

to do with the question of children’s love for their parents and their

respect for parents’ values. They need to maintain pride in their own

decision-making powers.

In fact, just to have the proud feeling of doing the right thing,

children may do what parents suggested “on their own.” They can only

achieve this feat if they first refuse to do something, and then do what

their parents want because they themselves “decided” to do it.

Any mother who has ever sponsored a Cub Scout meeting may remember that

her own child behaved the most poorly. The reason for the bad behavior

was simply that obeying mother in public can be construed by others in

the gang as childish. The only way to show that the child is no longer

hanging onto mother’s apron strings is to defy her openly. Stop your

child’s behavior or tolerate it—but do not discuss it in front of

other children.

The need to show up well in the group does not end with the preteen

period. The preteens have only begun practicing it. In many cases it

will be with them, and you, all through the teen-age years. And, sorry

to say, it is likely to get worse.

Toughness

Young children, when having problems, seek refuge in a friendly adult

apron. If serious problems hit teen-agers, they long for the friendly

shoulder of an understanding adult. Most preteens want neither—or if

they do, they would rather be “caught dead” than admit it.

The informal preteen group code views any friendly talk with an adult as

childish, sissyish, and cowardly. Also, according to preteen philosophy,

trouble is a source of pride, not shame. You do not have problems as a

preteen. You cause problems for others. Then they cause problems for

you, so you fight back or take it. It may be hard to handle, but it is

better to go under in glory than to ask for help or advice.

When preteens gather, they may not want “The Adults” intruding at

their parties.

Preteen love

Love in the preteen years is like a game. And it is a game that almost

every preteen in the group plays. Preteen girls spend much time trying

to get a “boyfriend,” and many preteen boys are busy trying to find a

“girlfriend.” But these friendships seldom blossom into love.

Most preteen boys and girls do not see the person of the other sex as a

love object in the way that will become apparent in adolescence. There

are, however, many exceptions to this, and a semblance of being in love

may become apparent from time to time. But preteen boys generally

consider girls merely as members of the other sex. Girls are acceptable,

or not, primarily on the basis

of the same criteria by which anybody else is acceptable to the group.

Girls operate in the same way, but they quickly tire of boys their own

age and develop “crushes” on older boys in higher grades.

During these years, boys and girls still consider each other “closed

groups.” The importance of getting a girlfriend or a boyfriend is in

winning the game. Then a girl can tell her less fortunate girlfriends

that she has a steady, that she is in love. And the boy can go bragging

to his buddies. Probably all they do is walk home from school, go to the

library, or go skating— accompanied by the group. Left alone they

might well have a hard time carrying on a five-minute conversation.