The preschooler’s education

Preschoolers’ constant questions reflect another side of development in

these years— their intense curiosity and their thirst for knowledge.

One of the most outstanding characteristics of preschoolers is that they

are so completely ready to learn—about the world around them, about

themselves as part of that world, about other children, and about

adults. Preschoolers are curious, open, and responsive. Their eyes go

out to all that is around them. Their ears pick up what is around them.

Their hands are tools for fascinated exploration.

One of the most important tasks for parents is to keep this burning

curiosity and charmed sense of wonder alive. Children will go far with

curiosity and wonder. Without them, now and in the years ahead, children

will have to be pushed or pulled or lured.

Trips to a fire station or other nearby places are treats for a

preschooler.

Most parents appreciate curiosity. Sometimes, however, without meaning

to, they discourage it. Curious children may trouble and frighten

parents. Parents worry about safety. When parents’ irritations or their

worries mount, the danger is that children will hear No and Don’t

and Be careful and Watch out too often. Parents must take

precautions, of course. But at the same time, they should make sure that

the world does not seem like a “bad” or “dangerous” or “not nice” place

to the child. Curiosity cannot stand a never-ending stream of

discouragement.

Parents must also be careful not to let their children’s curiosity

wither from lack of stimulation. Children desperately want to know more

and to understand their world.

Trips

Trips are one of the best ways of bringing new, stimulating,

mind-stretching experiences to young children. Preschoolers are

basically uninformed—they simply do not know much yet because they

have not lived long enough, or experienced enough. No one can really

tell children at this age about the world. The children do not yet have

the background or knowledge to understand the meaning of the words. They

have to see things first. They need firsthand experiences. Later, words

can build on these experiences. Trips, now, are a perfect solution to

learning for preschoolers.

Trips for preschoolers should be short. Young children tire easily, and

a tired, fussy

child learns little. The destination does not have to be spectacular,

either. To a young child, the filling station, the supermarket, the

florist shop, the post office, the barn, the stream, the airport, and

other everyday locations are a treat.

Time transforms an everyday “trip to mail a letter” or “trip to get a

quart of milk” into an educational experience. A good trip for a child

has a slow, relaxed pace with time for talking en route, both coming and

going. There ought to be time, too, for several short stops along the

way. Unexpected side explorations can sometimes be better than the main

trip itself. And at any stop, en route or at your destination, your

preschooler needs time to stand and watch, time to touch, time to

explore. Preschoolers cannot take in all they want to know at a glance.

On trips, there are countless opportunities to point out sights your

child might otherwise miss. And there are countless opportunities to ask

provocative questions that might not otherwise occur to the child.

Stories

Good storybooks, like good trips, stimulate children. Stories bring a

part of the world closer to them so that they can take a closer

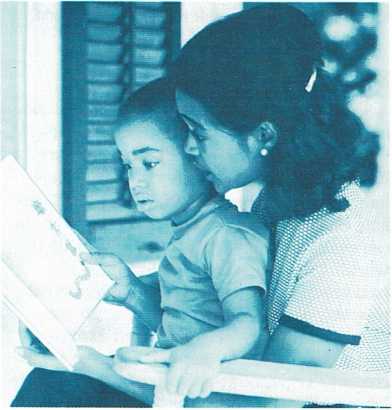

Story time is a time for companionship and conversation. Try to make

it a daily event.

look at it and come to understand it more fully. Stories may be

make-believe or about real people and events. They may involve animals

that seem almost human. They may include more adventure than most people

have in their everyday lives. But fiction or nonfiction, children’s

books help preschoolers get a better handle on the people, the events,

the objects in the real life that exists around them.

The trick in reading a story well to your child is the same trick as in

taking the child on a successful trip. Take your time. Do not rush to

the end of the story. Let your child interrupt to ask a question, even

if it takes you both off on a tangent. Story time should be a daily

event, and often an evening event—a time for companionship and

conversation between you and your preschool child.

Enriching the preschooler’s play

Language and social development, increased knowledge, longer attention

span, and vastly improved physical coordination all combine to produce

the most distinctive characteristic of preschool children. They are

highly imaginative and have the special capacity to make believe. They

can take on any roles that suit their fancy. There should be no fixed

roles for boys and for girls. The children themselves can become

anything they want to be—baby, cowboy, wild animal. A chair can become

a horse or a plane or an animal cage. To adults looking on, preschoolers

seem to spend all of their time “just playing.” The play of preschool

children is far from a waste of time, however. It is highly significant

activity that teaches important emotional, intellectual, and social

lessons.

Children at play draw on what they know. They very often play house, for

example, mostly because life at home is what they know best. The play is

imaginative, but it is firmly grounded in reality. The more children

know—the more places they have been, the more things they have

seen—the richer their play will be.

Preschoolers need toys and materials, too, with which to carry out their

play. The same toys are for all to use. They are not ear-

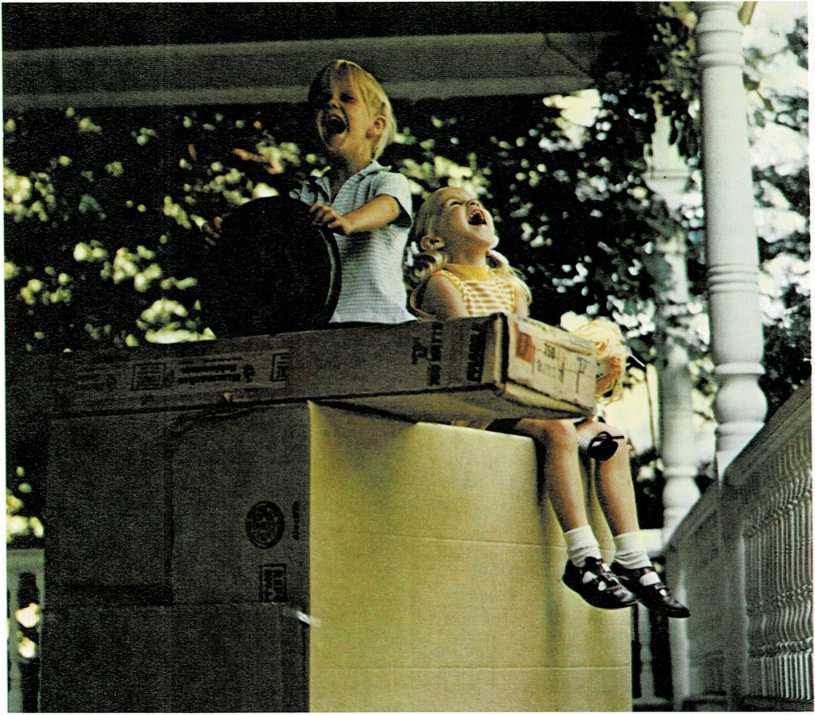

Boxes are toys that stretch a child’s imagination. They can be

whatever the child wants them to be—a car, a rocket, a grocery

store, a house.

marked “this is for boys” and “this is for girls.” Good preschool toys

set up rough outlines and give the child’s fertile mind freedom to fill

in the details. A tricycle, for example, is obviously some kind of

moving vehicle, but the child decides whether it is a horse, ambulance,

police car, ship, rocket, plane, bus, truck, fire engine, or tank. Among

the best playthings are boards, boxes, blankets, sand, cartons, wagons,

chairs, dolls, simple cars and boats, and other materials that can be

used in various ways. They let the richness come from a child’s own flow

of images.

One kind of imaginative activity is special to this age—creating an

imaginary playmate. Youngsters without many real age mates, and

youngsters who have no brothers

or sisters, are most apt to make up an imaginary friend. But even

youngsters with many real-life pals may add one more: their own,

personal, not-seen-by-adults child. The imaginary playmate can be

someone to boss or someone who gives support and comfort. This unseen

friend is important to a child. Try to make the few short-term

adjustments needed to fit this new member into your home.

Television and the preschooler

The fascination television holds for preschoolers is an indication of

their thirst for stimulation. TV’s fast-moving pictures and continuous

sound lure many young children into watching contentedly for hours. For

better or for worse, television is a teacher. Television viewing affects

children’s language and their awareness of the world around them.

Television also provides relaxation and entertainment. However, viewing

presents many hazards. There is reason to worry about the impact of TV’s

violence on the feelings and morals of youngsters, to be concerned about

the impact of commercials on their taste and the effect of long hours of

passive watching on their personality. One must also be concerned

because too much television viewing can rob a family of time for talk

and shared activities, and can also deprive children of creative play

with their age mates. The television set should not become a “baby

sitter.”

Some families react to these concerns by having no TV set. When TV is

available, it is important for parents to make thoughtful decisions

about what programs to view and how long children may watch. Involving

preschoolers in these decisions will offer them learning experiences

about choices and responsibilities.

It is also wise to watch television often enough with your children so

that you can discuss with them the ideas, feelings, and values the

programs may generate. You may also wish to consider becoming involved

with groups working to improve television for preschoolers. If good

programs are available, and if viewing hours are wisely regulated,

television can be a positive educational force. For further information

see [Children and television] in For Special Consideration.

Schools for the preschooler

Many 3- and 4-year-olds go to school. Some are in nursery school,

usually for half a day, because the parents want to supplement the

stimulation and companionship they can offer at home. And some 4-year-

olds go to public kindergartens. Other children of this age are in a

group situation all day because both parents work or because

they come from a single-parent family. These children usually go to a

day-care or child-care center.

It may be hard for some adults to imagine a “school” for children only 3

or 4 years old. “School” to these adults means a teacher in front of the

classroom, the children seated at desks, books as the major tool for

teaching, and the children hushed and quiet with no moving about.

Obviously, this is not the style of 3- and 4-year-olds.

The ways of schools for 3- and 4-year-olds fit the children who come.

The schoolroom is more like a workshop than a lecture hall. The

youngsters move about. They spend most of their time in small groups of

two or three or four. They begin to learn to live, work, and play

together. They learn to take turns, to settle disputes fairly, and to

cooperate. The program is also planned to let children use their bodies

well. A good school for children this age has both indoor and outdoor

facilities and gives ample time for climbing, balancing, swinging, and

other activities that build muscle coordination in preschoolers.

The children hear stories and music. They sing songs and take many

short, educational trips. They are surrounded by informative and

challenging pictures and exhibits. There is ample time for them to ask

many questions of their teacher and of their friends. Their knowledge,

their language, and their awareness of the world around them are always

growing.

The children also have the opportunity to express themselves through

block play, sand play, artwork of many kinds, and working with carpentry

tools and wood. Outdoors, they use such equipment as boards, boxes, big

blocks, tricycles, climbing apparatus, and wagons. They are almost

constantly involved in make-believe play—play that gives them the

chance to use their initiative, to think, to plan, to develop their

attention span, and to build their capacity for problem solving. (For

additional information, see [Day care] in For Special

Consideration.)