School days

Starting School

Starting school is a major adventure and a dramatic change from past

living. Most children can hardly wait to start school. They take this

challenge in stride, because their normal growth—in language,

attention span, social interests, curiosity, and independence—enables

them to welcome school without strain. There are, however, a few ways

parents can make it even easier for their children to move into school

life without emotional upsets.

Adjusting to school will be easier if children have had the experience

of being away from home without their parents. Children who have often

gone to the store with a neighbor, eaten lunch at a friend’s house, or

visited nearby relatives, or who have attended nursery school, usually

have no problem in leaving home to move into a classroom environment.

School adjustment will also be easier for children who have experienced

accepting people other than their parents as authorities. Children who

have been in the care of good baby sitters, for example, will probably

have less trouble accepting a teacher. Children who have played with

their friends in a neighborhood backyard or a house down the street,

responding to whatever mother was in charge of the play, have a

foundation for working with a teacher.

Most children beginning kindergarten or first grade know other

youngsters in their neighborhood who will be their classmates. Seeing

familiar faces helps a child adjust. If a child has no friends in

school, invite one or

two future classmates to your house to play, or for lunch, so that your

child can begin school knowing some of the children.

Most schools set aside one or more days in May or June for the

registration of children who will enter kindergarten the following fall.

At registration, the mother may have to present the child’s birth or

baptismal certificate. At a typical registration, children visit their

prospective classroom for a short time to meet their future classmates.

A few typical activities may be carried out, to let children sample what

kindergarten will be like.

Learning in the kindergartenprimary grades

Some school-age children approach learning (and life) in a systematic

manner. They proceed in logical, methodical ways. Others are cautious.

They move forward only when they are sure of themselves. Still others

dive in and then look around. Both parents and schools must recognize,

understand, and accommodate the child’s unique way of learning.

Practically speaking, the child in the kindergarten-primary grades is

taught to read, write, and work with numbers. The curriculum includes

language arts, social sciences, mathematics, science, music, and art.

These subjects generally are not taught as separate courses, though.

They are integrated into a total experience for the child.

A child learns best through firsthand experiences— seeing, hearing,

touching, smelling, and above all, doing. Children need

Hesitation, anxiety, anticipation, and fear are all a normal part of a

child’s behavior on the first day of school.

But there is time, too, for laughing and playing—for making new

friends in an environment completely unlike home.

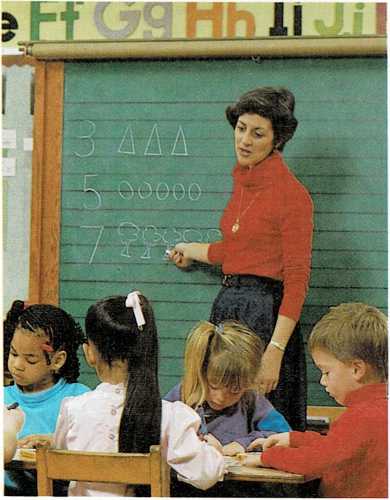

Then the learning process begins. Numbers must be mastered and objects

identified. Letters must be drawn and words formed.

At the end of the school day, children are happy to share with their

parents the work done and the many things learned.

these firsthand experiences before they can learn to read. Some children

arrive at school able to print, to identify letters, or even to read a

little. Others are almost totally illiterate—no great tragedy at age

5. By the end of the second grade, most children are reading—anywhere

from preprimer to fourthgrade level. Most understand the basics of

phonics. They are learning to associate the sounds in words with written

letters, and they are able to spell many words by applying some simple

phonetic rales.

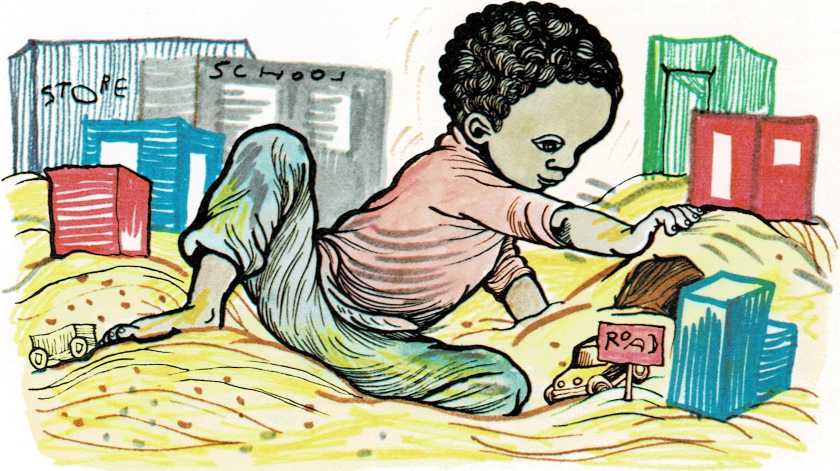

Social studies, in these early school years, generally means learning

about people and the world about them. A group of kindergarten children

studying their town may take trips to some of the important places in

the town. They may lay out a model of the town, using various sizes of

boxes for houses, stores, post offices, and schools. Trucks, cars, and

buses are placed on roads. People are made with modeling materials. And

there is much, much talk from the children—discussing observations,

asking questions, and checking impressions. Actually, what started out

as a study of “our community” moves into geography, economics, consumer

education, ecology, science, safety, history, mapmaking, and map

reading.

Science is experienced firsthand, too. For example, a child may prove

that a magnet will only attract things made of iron by conducting

experiments with a magnet and nails, paper clips, erasers, paper, and

fabric. Then the child may make magnets—a simple one from an ordinary

needle or even an electromagnet from a nail, a piece of wire, and a

battery. Next, the child may make a compass or a buzzer to discover how

magnets are used in different objects. By making these items, the child

understands better how they work.

School-age children enjoy music and art. Most of them love to sing, and

some even make up their own songs. They use rhythm instruments—-drums,

cymbals, tambourines—alone or to accompany a song or a record. They

like moving, dancing, and dramatizing or marching to music. Most

schoolage children like to paint, to work with clay, and to draw with

crayons and pencils.

School-age children also like stories and poetry. They enjoy being read

to. When given the opportunity to use their imagination, they compose

delightful stories and often write interesting poems.

The monthly calendar, displayed in jumbo size in many kindergarten

classrooms, is also

Imaginative children can create a city of their own with sand and

cardboard boxes.

A calendar is an aid for teaching a child about many things—time,

holidays, seasons.

a learning device. At first, the calendar does not mean too much to the

children. But as days go by, the children begin to learn the days of the

week, dates in sequence, weekdays and weekend days, and the meaning of

time and its components. The children have experiences with words,

letters, numbers, holidays, seasons, and changes in the outdoors.

The parent and the school

During these years, the basis for the home-school relationship is

formed. Conferences during the early years should serve both the teacher

and the parents by identifying and discussing the unique needs and

interests of the child.

Parents should try to meet their child’s teacher before the child starts

to school. At this meeting, parents should talk openly about their

child. Then, when school starts,

the teacher will already know something about the child and will be able

to help the child develop.

Most schools provide time for parentteacher conferences. At these

conferences, teachers can give parents samples of their children’s work;

describe the children’s behavior with other students and teachers; and

discuss their habits, attitudes, capabilities, strengths, and

weaknesses. Conferences give parents a chance to raise questions that

cannot be answered adequately by report cards, and they give the

teachers an opportunity to learn more about the child’s life outside

school. Conferences help parents and teachers work together to help

children reach their potential.

Parents should also meet the parents of other children in their child’s

classroom. These meetings can be informal—a coffee hour or an evening

meeting that includes both fathers and mothers. Or the teacher,

children, and parents may get together after a class play or other

special school function.

Inquisitive school-age children learn best when they can study

things firsthand.