Rash – Roseola

Rash. Since it is difficult to tell a mild, relatively harmless rash

from a serious one, consult a doctor if your child develops a rash which

persists and continues to spread, especially if the child is not feeling

well. Skin color can affect the appearance of a rash. A severe rash on

dark skin may appear milder than it really is. The following are some

common causes of rashes:

Measles—blotchy red rash, cough, conjunctivitis, fever

German measles—rosy rash, low fever, swollen glands in neck and

behind earsRoseola infantum—flat pink rash on the chest, abdomen, and neck

after high feverScarlet fever—a rash that looks like a sunburn with goose pimples,

usually associated with a sore throat and feverChicken pox—separate, raised pimples, some of which blister, then

break and crustEczema—patches of itchy, rough red skin

Hives—itchy white welts on red skin

Ringworm—circular, rough patches

Impetigo—blisterlike sores that crust

Prickly heat—raised, red, pinpoint spots, usually in the groin and

neck foldsDiaper rash—red, chafed-looking skin

Poison ivy—blisters and inflammation accompanied by much itching

Rocky Mountain spotted fever—purple spots on palms and soles, with

headache and fever following a tick bite. Take your child to the

doctor at once if you suspect Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

[a.m.m.]

Reye’s syndrome is an uncommon disease that occurs in children from

a few years of age to adolescence. It involves the liver and brain and

often follows an attack of chicken pox or influenza.

A child may be recovering from a mild respiratory infection when

suddenly there is persistent vomiting. This is followed by behavioral

changes consisting of lethargy alternating with irritability,

hyperactivity, and hallucinations. Should your child show such symptoms,

call your doctor immediately. If the diagnosis is Reye’s syndrome, the

patient needs emergency treatment and should be taken to a hospital

equipped to give all the help necessary.

This disease is named for Dr. R. D. K. Reye, who, with Australian

colleagues, first described cases of it in 1963. Its cause is still

uncertain and proper treatment is unclear. The general aim is to reduce

the brain swelling and restore normal liver metabolism. Most patients

also have a high blood ammonia level which must be lowered, [si.

k]

Rh factor is a chemical substance that most people have in their

blood. It gets its

name from rhesus monkeys, in whose red blood cells it was first

discovered. The Rh factor is inherited. If the factor is present in a

child’s blood, the blood is Rh-positive. If the factor is absent, the

blood is Rh-nega- tive. Both types of blood are normal and healthy, but

they do not always mix safely.

For example, if a child with Rh-negative blood receives a transfusion of

Rh-positive blood, the Rh-positive blood may cause production of

antibodies that attack the child’s normal red blood cells. The child may

become seriously ill or even die. Hospital technicians test a child’s

blood to determine the Rh factor before transfusions are given.

It is also important to know the Rh factor when a woman is pregnant, or

when a husband and wife are planning to have a baby. The baby of an

Rh-negative mother and an Rh-positive father may be Rh-positive or

Rh-negative. If the baby is Rh-negative, there is no problem. But if the

baby is Rh- positive, the blood may cause the mother’s Rh-negative blood

to produce antibodies against the Rh factor. These antibodies may then

return to the baby’s blood and destroy the red blood cells. The

infant—commonly called an “Rh baby”—may die before birth or may be

born with mild to severe jaundice and anemia. The opposite condition—

an Rh-positive mother and an Rh-negative baby—does not cause trouble.

Once the blood of an Rh-negative woman starts to produce antibodies, the

level of antibodies becomes progressively stronger with each Rh-positive

pregnancy. Generally, an Rh-negative woman with an Rh-positive husband

can have two or three healthy Rh- positive babies because her antibody

production may be slow enough that these first babies escape its

effects. But if an Rh-nega- tive woman has ever had a transfusion of

Rh-positive blood, her blood may already contain antibodies that can

react dangerously with her baby’s Rh-positive blood.

With correct and immediate treatment, a seriously affected Rh baby can

usually make a good recovery and be normal. Doctors can detect Rh

incompatibilities by simple blood tests that measure the level of

antibodies. If the level rises threateningly, the doctor may induce

early labor so that the baby can be delivered before the level of

antibodies is

dangerously high. Sometimes, exchange transfusions must be given to the

baby immediately after birth. These transfusions replace the baby’s

blood with fresh blood. In rare cases, transfusions of blood have been

given to unborn infants. Transfused blood must be Rh-negative, because

Rh-positive blood would be destroyed by the antibodies in the baby’s

system.

For protection in future pregnancies, a vaccine is available to prevent

the production of antibodies in the mother’s blood. It may be given to a

mother with Rh-negative blood within 72 hours after delivery or

miscarriage of an Rh-positive baby.

The best protection against the heartbreak of an Rh baby is competent

prenatal care. A doctor can take proper measures to have on hand the

equipment, typed blood, and other materials for treating the Rh

condition. [k>.]

See also Anemia; Blood type; .Jaundice

Rheumatic fever is a disease that follows an untreated infection by

group A beta hemolytic streptococcal bacteria. The infection is usually

a strep throat. Rheumatic fever, now an uncommon disease, usually first

strikes between the ages of 5 and 15.

Symptoms of rheumatic fever generally appear within two to five weeks

after the strep infection has cleared up. Chorea (St. Vitus’s Dance),

with uncontrollable twitching of muscles, may be one of the first

symptoms. Or, the child may have vague pains in the muscles. (However,

the great majority of children with muscle pains in their legs at night

do not have rheumatic fever.) These pains may become intense. The joints

in the child’s legs and arms may become red, painful, and swollen. The

child may also have a fever and a skin rash. At the same time, the heart

and the heart valves usually become inflamed. This inflammation causes a

heart murmur.

Rheumatic fever can cause permanent damage to the child’s heart, but not

always. When permanent damage does occur, it usually results from

inflammation of either or both of the valves on the left side of the

heart. As the inflammation lessens, a scar forms on the valve. This scar

prevents the valve from opening and closing properly.

The damaged valve may allow blood to leak back when the heart contracts.

Or, the valve may become so puckered and shrunken that the child’s heart

can scarcely force blood through it.

If you suspect that your child has rheumatic fever, consult your doctor.

The doctor will likely advise hospitalization of the child. Bed rest

during the severe phase of the disease is essential for a child with

rheumatic fever. Convalescence at home may be necessary for a time. The

doctor will probably prescribe a gradual increase of physical activity

as well as acetaminophen, and, in special cases, steroid medications to

relieve the symptoms.

A child who has had rheumatic fever is not immune to it. The child is

susceptible to recurring attacks. Each additional attack may damage the

heart valves. Eventually, the valves may become so scarred that an

operation is necessary. Strep infections are a greater threat to a child

who has already had rheumatic fever. To protect the child, the doctor

will prescribe a long-term program to prevent a strep infection. The

child may receive a daily oral dose of a sulfa drug or an antibiotic

such as penicillin, or may have an injection in the buttocks of a long-

acting antibiotic once a month. This protective treatment may be

continued until the child is about 21 or even older.

The best way to fight rheumatic fever is to prevent it. Call your doctor

if your child has a sore throat with a fever, a persistent sore throat,

or an extremely sore throat. The doctor may want to take a throat

culture, because this is the only way to identify the beta hemolytic

streptococcus. If the doctor finds this streptococcus, antibiotics will

be prescribed immediately. This treatment will continue until another

throat culture shows that the infection has cleared up. Fortunately,

most sore throats are not strep throats, [m.g.]

See also Arthritis; Chorea; Cramps; Growing pains: Heart murmur;

Strep throat

Rickets is a bone disease caused by a metabolic disturbance in the

body. Some children with rickets do not get enough vitamin D in their

diets. Others have an inherited

disability that prevents absorption of vitamin D from food. Rickets is

extremely rare in the United States and Canada.

In most cases rickets occurs before the child is 3 years old. The bones

of the child do not calcify (harden) adequately. They are so soft that

they can bend out of shape. Bumps can also develop on the bones. Severe

rickets causes bowed legs, short stature, and deformed skull, rib,

backbone, and pelvic bones. Bone damage can be corrected if it is not

too severe. If rickets is not corrected, the bones may eventually harden

and leave the child misshapen, [mg.]

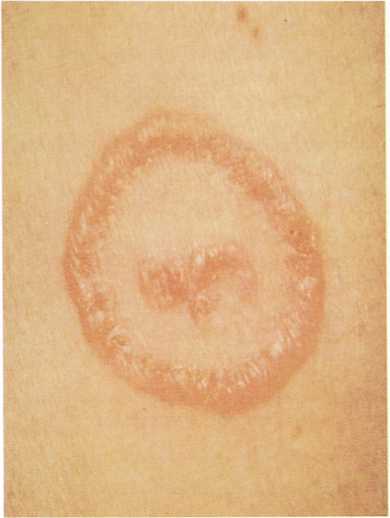

Ringworm is a contagious skin disease caused by fungus. It may be

itchy. Ringworm of the body usually appears as scaly, circular, pinkish

patches. As a patch grows larger, the center clears and the eruption

looks like a ring. Ringworm of the scalp is characterized by round, red,

scaly patches in which hairs break off close to the scalp. Ringworm

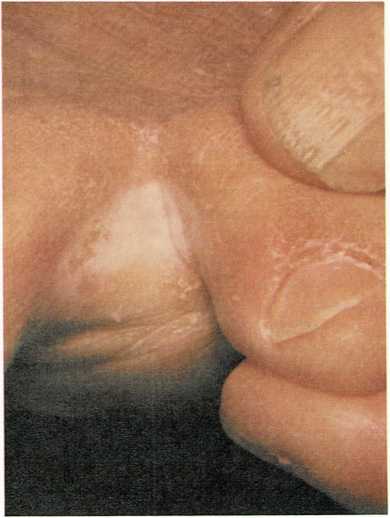

infection of the feet, commonly called athlete’s foot, usually appears

in the

webs of skin between the toes. It usually produces cracked, itchy,

tender skin. Blisters and scaly skin may appear on the soles and sides

of the feet. If you think your child has ringworm, call your doctor.

Antifungal drugs can clear up the disease.

Ringworm may be spread by contact with infected people, infected dogs or

cats, or infected brushes, combs, and furniture. Children who have

ringworm should use their own combs, brushes, washcloths, towels, and

other personal articles. They should be cautioned against scratching the

infected areas, because if they scratch, they may spread ringworm to

other parts of the body, [a.m.m]

Roseola infantum is a disease characterized by a rash and a fever.

Doctors believe that it is probably caused by a virus. Roseola infantum

usually affects children between 6 months and 3 years of age.

Roseola infantum usually begins with a fever of 103° to 105° F. (39.4° C

to 40.6° C). After three to five days, the child’s temperature suddenly

drops to normal or below.

Small, circular patches of pink skin are characteristic of ringworm of

the body.

Athlete’s foot usually produces cracked, itchy, tender skin between

the toes.

Then a rash of small, pink, flat spots appears on the chest, abdomen,

and neck. Only rarely does it spread to the child’s face, arms, and

legs. The rash may last a few hours or one or two days. One attack

usually provides permanent immunity.

Call the doctor if you suspect that your child has roseola infantum. The

,doctor will probably tell you to give the child acetaminophen to bring

down the fever and liquids to prevent dehydration. You do not have to

isolate a child with roseola infantum. [h.hr.,] Jr.

Rubella. See German measles