Portrait of the preteen

Preteens are not quite the children they were. And yet, they are not

quite the teenagers they will become. They are in a transitional

period—a period of preparation.

Something new is going to be added, and for this reason they are

changing. They are something like a department store that is undergoing

renovation while still conducting business.

Preteen changes and preparations may shake children’s personalities.

These children

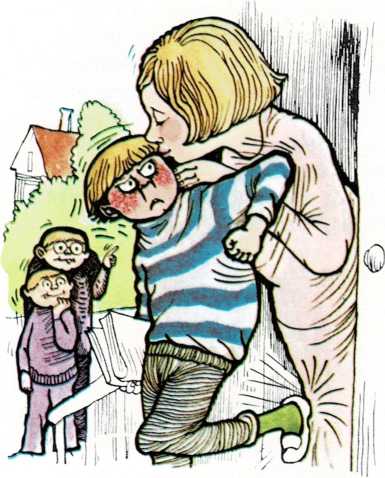

Preteens often avoid shows of affection.

used to be fairly easy to get along with and eager to please. Suddenly

they become reluctant and defiant. Boys who used to pride themselves on

keeping a neat room drop their clothes on the floor as they make their

way to the bathroom for the nightly shower. Girls who depend on parents

for the choice of their clothes suddenly break down in tears when an

adult makes the slightest comment on their appearance. Reluctance,

defiance, and tears—all are characteristics of preteens.

When children were younger, they usually relied on their parents’

judgment. They felt safe and secure and had pleasant personalities. But

during the preteen years, they pick up new ideas. They make more of

their own judgments, and they are not always confident that their

judgments are correct. They become less secure, and as a result their

personalities may become a little less likable. Every preteen goes

through this to a certain extent. It is part of loosening up the

childish personality to make room for the independent adolescent

personality. A child’s adolescence may, in fact, actually “begin” during

this preteen period.

The body itself—especially a girl’s—is preparing for the changes and

additions brought on by puberty. And, of course, the preteen is

preparing to move away from family ties—a move that will be the

child’s major task during the teen-age years.

This time of preparation and change begins around the end of the fifth

or sixth grade and usually lasts into the seventh or the beginning of

eighth grade. As in all de-

velopmental stages, exact ages cannot be- given. Individual differences

in physical, intellectual, and emotional growth are as varied as are the

circumstances under which youngsters go through such a phase. Also, not

every child gets hit by this change in the same way, nor in all areas of

life at the same time.

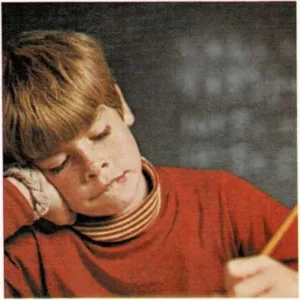

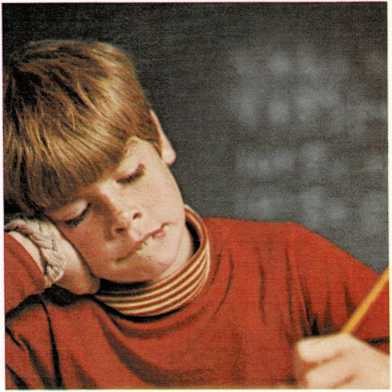

Restlessness

If your preteen reaches for gadgets on your desk while you are having a

serious talk, don’t think the child is being disrespectful. Fiddling

with everything in sight while supposedly doing homework does not mean

the child wants to play instead of work. The preteen literally cannot

help it. Any gadget in sight must be handled. This “manipulative

restlessness” is enormous. Workbooks look as though they had been fished

from last year’s trash can. Pencil tops are chewed up long before the

writing parts are even slightly used. And if no gadgets are around, then

body parts are acceptable substitutes. The child may pull at one earlobe

or the other, drum fingers on the desk or table, scratch at elbows, or

twist locks of hair.

The preteen’s restlessness also shows up in a short activity span. Most

preteens cannot stick to anything for long, even if it is something they

enjoy—an experience for which they have been longing.

Parents should try to allow for their pre- teens’ restlessness, and when

they have to interfere, they should do so in a reasonable and friendly

way, without showing indignation or excitement. They should try to

provide opportunities for children to rid themselves of restlessness

with as little disturbance to others as possible. For instance, periods

of quiet work can be broken up with some activity—giving preteens a

chance to move around, stretch, sing, talk, and yell. Preteens just

cannot be forced to spend most of the day sitting and writing, reading,

or listening. If parents or teachers can suggest ways for preteens to

satisfy the need for activity and manipulation, the children will

probably find it easier to remain quiet when they must study or do other

things that require sitting still.

The restless preteen is almost always in motion.

Even when seriously at work, a preteen may be biting a lip or

chewing a pencil end.

Talking, laughing, shifting in a chair—the preteen finds it hard

to do “nothing.”

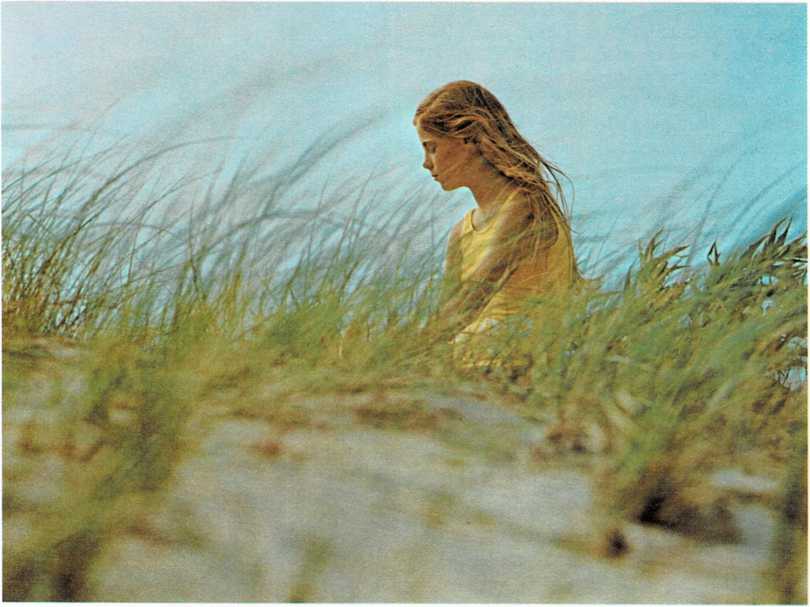

Almost every preteen indulges in daydreams—fantasies that help the

child deal with new feelings or feelings that are not easily

expressed.

Also, remember that children cannot easily change preteen habits and

behavior patterns. They have to go through this stage. They do not

purposely do these things to annoy adults. Parents should avoid constant

nagging and reminders that make preteens embarrassed and self-conscious.

Forgetfulness

Preteens forget. And, there seems to be no excuse—especially since

they can remember things their parents wish they would forget. For

example, a teacher assigns homework on Friday to be turned in Monday.

The teacher writes the assignment on the board and makes half the class

repeat it. Yet on Monday, when the assignment is due, a third of the

class has forgotten all about it.

Obviously, children sometimes use forgetting as an alibi. The amazing

thing is that half of those who said they forgot were tell

ing the truth. They really forgot. Preteens block out things that

interfere with their pursuit of happiness. These memory blocks save them

from unpleasant guilt feelings. A person who really forgets obviously

cannot help it. Remind your preteen of obligations, but try to do so

without nagging.

Daydreaming

Otherwise alert preteens may stare into space in the middle of a class,

even when the subject is one they are good at and interested in.

Youngsters of other ages can tell you what they daydream about. However,

if you ask preteens what they were thinking about they usually answer,

“Nothing.” This may not be an evasion. Preteens have an extraordinary

ability to think of nothing—or at least nothing that they can describe

or name. Frequently, their daydreams are not organized at all. One

picture after another flits through their

minds. You might compare this to your own thoughts just before falling

asleep.

When there is content in the daydreams, this varies as widely as do

preteens themselves. However, two basic kinds of daydreams dominate

preteen fantasies.

One is a “technological” daydream. Many technically inventive and gifted

children spend a lot of time looking at such things as a speck on the

wall or a piece of string or wire. In their minds, such spots of color

or pieces of metal or wood combine in the widest range of possibilities;

they see “gadgets.” Children may come out of such technical daydreams

with imaginative, demonstrable products.

The other trend in daydreams concerns extreme power, cruel victory,

destruction, fear of destruction, rebellion, mourning, and so on. They

include the whole range of emotional relationships the preteen lives

through, moves away from, or contemplates moving into. Many people worry

that comic books and television create these daydreams. Indeed, such

things may at one time or another be the cause. But if comic books and

television were not available, children would still daydream about

unpleasant things.

Daydreams fill a need of youngsters who are leaving one world

(childhood) and wondering about entering another (the teen-age years).

They must deal with puzzling and unpredictable themes, but cannot deal

with some of them directly because they would be punished by shame,

guilt, terror, panic, fury, or rage. So they daydream.

For example, if a boy dreams of cruelly killing a wild monster, it may

not mean that he has such wild needs troubling his soul. It may simply

mean that he was terribly embarrassed the day before when his father

scolded him in front of his buddies. The child cannot consciously direct

rage against his father, because he loves his father and knows his

father was right. However, the shame still burns. How can he deal with

it? He does so in the same way he deals with otherwise unmentionable

pain—he projects it into the future or the past. He makes familiar

people into strange ogres or powerful enemies. He destroys with

vehemence something that obviously cannot have anything to do with his

real life. Only then can

he let out the total force of his anger or panic or guilt or shame or

rage.

Success and praise

For young children, rewards that are “deserved” are especially

gratifying. Things received only by “chance,” while pleasant, are not a

source of pride. Not doing a job or assignment is shameful, while

“working hard at it” is something to be proud of.

During the preteens, this view of success and failure may suddenly

reverse, at least in part. Preteens are especially proud of what they

get away with. The fact that they worked hard on an assignment may be

embarrassing, and they may even try to hide what they did from their

group. To get something undeservedly (“This stupid teacher doesn’t even

know I haven’t done any work at all!”) seems to be the height of glory.

Argument against this attitude is not effective. Actually, many

youngsters pretend this attitude, though they do not mean it. But the

group code demands that preteens make light of their virtues, brag about

shrewd evasion of the consequences of their actions, and glory in the

luck or skill that brought them ill-gotten and undeserved gain.

It is easy to see, then, why youngsters of this age often react

irrationally when praised. For preteens, open praise makes them think

they are being treated like babies or teachers’ pets. Praise may be more

painful to them than the praising adult can imagine. If a preteen is

told that he has acted like a “little gentleman,” or that she has acted

like a “little lady,” chances are that the child will be insulted rather

than complimented.

Even the type of argument used with preteens needs examination. A boy

may well accept the fact that you want him to come to dinner with clean

fingernails. But arguing that a “nice little boy” would not want to

appear with dirty fingernails is like throwing gasoline on a burning

fire. Anything that makes preteens feel that you are treating them “like

little kids” hits the youngsters the wrong way. This does not mean that

parents should not interfere. But, they should try to treat their

children as the maturing young people they are.