Poisons

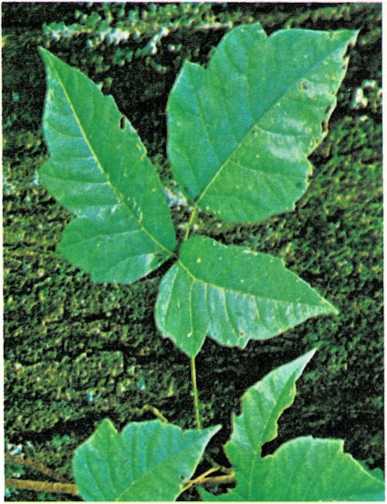

Poison ivy, oak, and sumac are three common and closely related

plants that cause skin rashes. A child who spends a great deal of time

in the woods and fields should know what these plants look like so that

they can be avoided.

Poison ivy leaves grow in clusters of three, all from the same stem.

The edges of the leaves may be lobed or notched.

Poison ivy grows as a vine or shrub. Some forms of poison ivy are called

poison oak. Poison ivy always has three smooth leaves on one stem. The

leaves are shiny green in summer and turn red or orange in the fall.

Bunches of small, green flowers grow on the main stem close to the

leaves. In autumn and winter, the plant bears clusters of white, waxy

berries.

Poison sumac grows as a shrub or small tree. It has narrow, fernlike

leaves and drooping clusters of white berries.

Poison ivy or poison sumac rash is caused by an irritating oil in the

leaves, flowers, fruit, stem, bark, and roots. Clothing that has come in

contact with poison ivy may irritate the skin just as much as the plants

themselves. Wash or clean the clothing before the child wears it again.

Dogs and cats that have come in contact with the poison ivy may also

cause the rash. Decontaminate your pets by bathing them.

If you think your child has touched poison ivy, immediately wash the

child’s hands and other exposed skin thoroughly with mild soap. Rinse

with plenty of cold water, lather

again, and rinse again. Do not rub too hard and do not use brushes,

sponges, or other rough or harsh materials. Washing with soap removes or

lessens the irritation of the oil.

Poison ivy rash may appear a few hours or a few days after the child

touches the plant. At first the child’s skin itches or burns. Then the

skin becomes inflamed, and it usually develops blisters. Scratching may

cause an infection. Cut the child’s fingernails short. To reduce

itching, soak the rash- covered skin in plain or salt water for 20 to 30

minutes, four or five times daily. Use one level teaspoon of table salt

in one pint (0.5 liter) of water. Apply calamine lotion every two or

three hours. Your doctor may prescribe medicine such as Benadryl® to

reduce itching, [a.mm]

Poisonings and poisons. According to the National Capital Poison

Center, approximately 1,500,000 poisoning cases occur each year. Of all

reported accidental exposures to poisonous substances, 65 per cent

involve children under 6. In addition, an unknown number of poisoning

cases are not reported to poison control centers.

Cases that are reported to poison control centers include exposure to a

wide variety of chemical substances such as cosmetics, plants, cleaning

substances, analgesics, and cold and congestant medications.

Approximately 65 per cent of the incidents are nontoxic, rather than

cases of actual poisoning. Approximately 35 per cent are considered

toxic exposures, or actual poisonings that involve symptoms,

hospitalization, or death.

Factors that affect poisonings. Many factors determine the eventual

outcome for a potentially poisoned child or adult:

The inherent toxicity of the material itself; for example, household

bleach as compared to cyanide.The concentration of the substance ingested (taken in); for example,

bleach drunk straight from the bottle as opposed to a cupful diluted

in a bucket of water.The sensitivity of the child to the substance in question.

The route of the exposure; for example, gasoline spilled on the skin

as opposed to gasoline swallowed during siphoning.The volume or amount ingested.

The time interval since the exposure.

The presence or absence of symptoms.

The number of substances ingested.

The ability to follow instructions from a poison control center or

doctor. Often an appropriate and timely reaction to an incident can

mean the difference between taking care of the problem at home and

going to the emergancy room of a hospital.

How and with what children are poisoned. Cosmetics are the leading

poisonous substance ingested by children under 6. Other leading

poisonous substances, in order, are plants, soaps and detergents, cold

medications (antihistamines or decongestants), analgesics, and vitamins

and minerals.

Aspirin was once a major poison problem with children. However, since

1972, the number of aspirin-related poisoning incidents has declined

steadily. One factor is the Poison Prevention Packaging Act of 1972,

which requires child-resistant packaging. However, other common

household analgesics that are provided in child-resistant packaging show

a slow but steady increase in frequency of ingestions. Unfortunately, no

packaging is absolutely childproof.

Therefore, a number of factors other than child-resistant packaging are

believed to account for the reduction in the number of aspirin

poisonings. The most significant factor is thought to be increased

public awareness of the danger of aspirin. Evidently, parents recognize

the potential danger of aspirin and use and store it properly—out of

sight of curious little minds and out of reach of curious little hands.

The same need for safety precautions applies to all potential poisons in

the home, including acetaminophen, which has replaced aspirin in the

treatment of fever.

Poison prevention. Normal children are inquistive, resourceful, and

almost tireless. They learn by touching, smelling, and tasting the

elements of their environment, and by imitating their parents and other

family members. If an item is attractive in appearance or packaging, is

brightly colored, resembles a food item, or has been consumed by other

family members in the child’s presence, it is a potential poison.

Observing some safety rules, and checking or cleaning

out a few areas of your house, can help protect your child from

poisoning and perhaps help prevent needless pain to both your child and

you.

Safety rules. By following a few simple safety rules, you can

“poison-proof” your home:

Keep hazardous products out of your child’s sight and reach.

Periodically check the entire house and all storage areas for

hazardous materials. Discard any potential poisons that are of

little or no use. Some items commonly involved in poisonings are

furniture polish, lighter fluid, bleach, boric acid, turpentine,

pesticides, antifreeze, drain cleaners, and medicines. Store all

colognes, perfumes, and aftershave lotions (which are all high in

alcohol content) and all “super” glues out of reach.Take extra care during times of family stress or any disturbance of

normal routine (for example, when moving or going on vacation,

during illness, or during holidays).Never refer to medication as candy.

Purchase only those medications and household products that are

available with child-resistant closures. Use these packages as

directed.Never leave alcoholic beverages within your child’s reach. Before

retiring, always discard any alcoholic beverages left in glasses or

cans and empty all ashtrays.Always read the warning labels on hazardous products.

Keep all products in their original containers.

Never put nonedible or hazardous products in cups, pop bottles, or

other containers that would normally be used for food or beverages.Avoid taking medication in the presence of your child.

Promptly dispose of any leftover medication used to treat an acute

illness.Teach your preschoolers not to eat or drink anything unless given to

them by an adult they know.Do not depend on close adult supervision. A child moves quickly, and

with purpose.Be alert for repeat occuiTences. For some unknown reason, a child

involved in an improper exposure or poisoning is likely to attempt a

second ingestion within one year.

“`{=html}

“`

Know the names of all your house plants. Keep potentially toxic

plants out of your child’s reach.Maintain your furnace in good working order. This will help prevent

both natural gas and carbon monoxide poisoning.Keep the telephone number of your physician, hospital emergency

room, and poison control center near your telephone.Seek professional help if your child swallows any nonfood substance.

Keep a one-ounce bottle of syrup of ipecac in your home medicine

chest. This is used to induce vomiting in some poisoning

situations. But do not use syrup of ipecac without professional

advice. In 95 per cent of all cases, syrup of ipecac will cause

vomiting within 30 minutes.Do not use outdated, ineffective, and potentially toxic methods of

inducing vomiting, such as mustard, salt water, or copper sulfate.

In some circumstances, inducing vomiting can have a harmful effect

and may actually create a serious situation from what would have

been a benign ingestion.Do not attempt self-directed home treatment of a poisoned child.

Call the local poison control center.

Guidelines for parents. If a child swallows a nonfood item or is

exposed to toxic fumes, a few basic rules may help to minimize both

physical and emotional trauma to the child and family:

Remain calm.

When possible, estimate the amount ingested or duration of exposure

to the solvent or fumes.Observe the child for symptoms or unusual behavior.

Try to estimate the elapsed time since the ingestion or exposure.

Bring the container to the telephone in case there are questions

about the substance.Call the poison control center.

If the child vomits spontaneously, do not discard the vomit.

If a significant time lapse occurs between ingestion and your

realization of the exposure, save approximately two ounces of each

urine specimen produced. Both vomit and urine may be analyzed if an

emergency room examination is necessary.

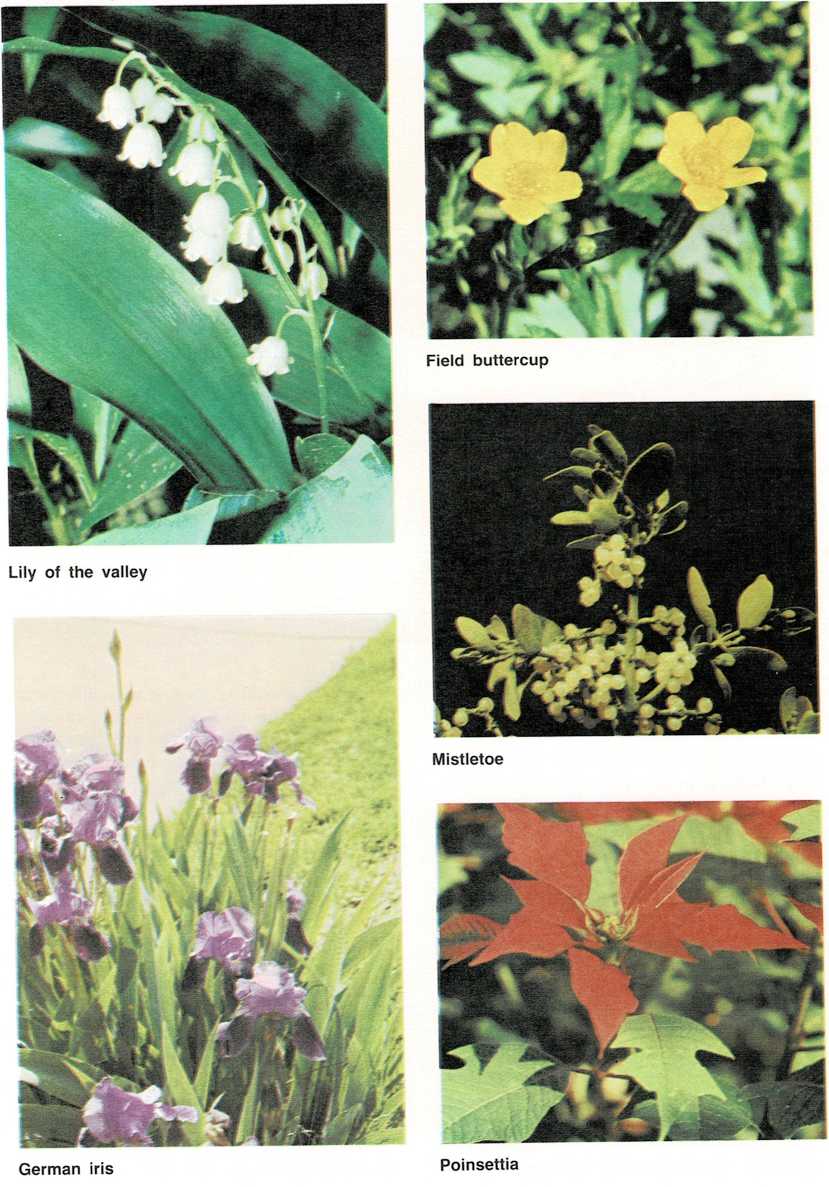

Outdoor plants that are poisonous when eaten

A partial list of toxic plants

(All or some of the parts of these plants are poisonous.)

Aconite Deadly Nightshade Jimson Weed Poinciana

(Monkshood) Delphinium Jonquil (Bird of Paradise)

African Violet Devil’s Ivy Lantana (Red Poinsettia

Sage

Amaryllis Dieffenbachia* or Wild Sage) Poison Hemlock

Azalea (Dumbcane) Lily of the Valley Poison Ivy

–^1^

Begonia Elderberry Lobelia Poison Oak

Black Locust Elephant’s Ear Marijuana Poison Sumac

Black English Ivy Marsh Marigold Pokeweed

Nightshade

Bleeding Heart Flax Milkbush Pothos Plant

(Dutchman\’s- Four-O’Clock Mistletoe Privet

(berries

breeches) Foxglove Moonseed and leaves)

Buckeye Golden Chain Morning Glory Rhododendron

Buttercup (Laburnum) Mother-in-Law Scotch Broom

Caladium Holly Mountain Laurel Shamrock

Calla Horse Chestnut Mushrooms Star of

Bethlehem

Christmas Hyacinth (various wild types) Tobacco

Cherry

Christmas Rose Hydrangea Narcissus Tulip

Chrysanthemum Iris Oak Virginia

Creeper

Crocus, Autumn Jack-in-the-pulpit Oleander Water Hemlock

(Meadow Crocus) Jequirity Bean Pansy (seeds) (Cowbane)

Crown of Thorns (Rosary Pea) Pencil Tree Wisteria

Daffodil Jerusalem Cherry Peony (common) Woody

Nightshade

Daphne Jessamine, Yellow Philodendron* Yew

\’These are the most poisonous house plants.

Cautions. Do not attempt home assessment or home treatment of a

poisoned patient. Do not rely upon a poison antidote/ treatment chart.

Call upon the professional experience of personnel who routinely treat

poisoned patients. Inducing vomiting can worsen the patient’s condition

in certain situations.

For example, you might cause unnecessary injury by inducing vomiting if

the child has ingested certain stimulants, strychnine, an acid or an

alkali, or certain petroleum products (depending upon the nature and

volume ingested), or if the child is unconscious or having a seizure.

Eye contamination. The one situation in which it would be advisable

to begin treatment before seeking professional assistance is in the case

of eye contamination. If damage occurs to the cornea (clear portion of

the eye), it may cause a partial or complete loss of vision. An eye that

has been exposed to

an irritant should be flushed with lukewarm water for 15 minutes. If

more than one adult is present at the time of the exposure, one can

flush the eye while the other contacts a physician, emergency room, or

poison control center.

Several methods of eye washing are possible. The quickest method is to

use a soft stream of lukewarm water from a kitchen faucet. Check the

water temperature several times during the washing, because the

temperature may increase or decrease. Remember to use a gentle stream of

lukewarm water so as not to cause further injury to the contaminated

eye.

The second option is to fill a pitcher with lukewarm water and slowly

pour the water over the eye for 15 minutes. You may need several

pitchers of water to complete a 15- minute flush of the eye.

Any form of eye washing is difficult. If the child is particularly

uncooperative as a result

of pain or fear, the parent has two options. The first would be to step

into the shower with the child, using the shower spray to decontaminate

the eye. Do not waste time removing either the child’s clothes or your

own. Using the shower, however, can be difficult because the force of

the water may contribute to the irritation of the eye.

Second, the parent who is alone and dealing with a combative child may

wish to ask a neighbor for help. But, if you have to work on your own,

wrap the child in a large towel, sheet, blanket, or pillowcase. Keep the

child’s arms inside the wrap. Using a chair to prop your knee up, you

can hold the child on your knee with one hand and, after adjusting the

water temperature, hold the eyelids open with the other hand.

Skin contamination. Another area in which you can do something

before calling for professional assistance is in treating the skin

following exposure to acids, alkalis, petroleum products, or

insecticides. Remove the child’s clothing and bathe the child

thoroughly. Areas that children often wash inadequately include the

fingernails, behind the ears, the groin area, and the scalp. Failure to

wash these areas thoroughly can provide sites for the continued

absorption of the contaminant. Be careful not to splash soap or

contaminated water into the child’s eyes during the bathing process.

Articles made from porous material such as leather cannot be

decontaminated after exposure to most liquid organic substances. Shoes,

belts, watchbands, or other articles made from leather must therefore be

discarded once contaminated.

Warning. Remember, all substances are poisons. There are none that

are not poisons. Only the right dose, administered under the appropriate

circumstances, constitutes a remedy for a poison.

See also Accidents; Bites and stings; Coma; Convulsions; CPR;

Emetics; Food poisoning; Medicine cabinets; Poison ivy, oak, and sumac;

Prescriptions; Vomiting

Symptoms of polio may at first resemble those of a common cold. The

child may have fever, chills, sore throat, headache, severe intestinal

upset, stiff back, muscle spasms in the neck or thighs, or pains and

stiffness in the legs, back, and neck. Some children become paralyzed,

but most do not remain paralyzed permanently. All children with polio

should be under a doctor’s care.

Vaccine has almost eliminated polio in the United States and Canada. The

first vaccine perfected was the inactivated Salk vaccine, in which the

virus is dead but still able to cause production of antibodies. Later, a

live oral vaccine was developed by Albert Sabin. This vaccine contains

the living poliovirus, but the virus has been weakened so that the child

does not catch the disease. Live vaccine provides longer-lasting

immunity, and so children who have been immunized with the Salk vaccine

should also receive oral vaccine.

Giving the oral vaccine is simple. Two drops of the vaccine are dropped

directly into the child’s mouth or onto a small lump of sugar, which is

then fed to the child.

Three types of viruses cause polio, and so a child must be protected

against all three. Type I is the most frequent cause of polio. Type III

is the next most frequent cause, and Type II is the least frequent

cause.

There is an oral vaccine for each of these three types. The doses can be

given separately. These vaccines, called MOPV (monovalent oral

poliovirus vaccine), are most helpful to doctors during an epidemic

caused by a single type of polio.

For routine immunization, most doctors prefer TOPV (trivalent oral

poliovirus vaccine). This vaccine protects against all three types of

polio. It is usually given at 2 and 4 months of age, with a third dose a

year later. If a child is at risk for exposure to polio, an extra dose

of TOPV may be given at 6 months. Many doctors also recommend a fourth

dose of TOPV at 4 to 6 years, or when children enter kindergarten or

first grade, [h.d.r.,] Jr.