Malocclusion – Meningitis

Malocclusion is the failure of the teeth of the upper and lower jaw

to meet properly in biting, or when the mouth is closed. It is caused by

irregular placement of the teeth. Malocclusion is also called poor bite.

Malocclusion may occur in both primary (baby) teeth and permanent teeth.

It may be inherited; it may be acquired; or a combination of these

factors may cause it.

Some children lose their primary teeth too early because of decay or

injury. Then, when the permanent teeth come in, they may shift out of

position because the guiding channels left by the primary teeth may have

changed. Some primary teeth stay in too long and push the permanent

teeth out of position. Children who suck their thumbs or fingers

excessively after the age of 5 or 6, when the permanent teeth are coming

in, may also develop poor bite.

Loss of permanent teeth can leave gaps in the child’s jaws and, unless a

retainer is inserted, cause the remaining teeth to drift (lean out of

position) into the gap.

Children with malocclusions may encounter several problems. They may not

be able to chew food properly, or they may have trouble cleaning their

teeth. Protruding front teeth or teeth crowded into small jaws may make

children feel self-conscious because they look different from other

children. Too much space between the teeth may impair children’s speech.

All children should start going to the dentist when they are about 3

years old, and they should visit the dentist periodically. The dentist

who checks your child’s teeth regularly will be able to recognize signs

of malocclusion when they occur. The dentist can advise you if the child

should see an orthodontist (a dentist who specializes in correcting

irregularities of teeth and jaws). Malocclusion can be corrected by

braces, [mg]

See also Braces, dental; Teeth and teething

Measles (rubeola) is a highly contagious disease caused by a virus.

Measles can be prevented by vaccination, and doctors usu-

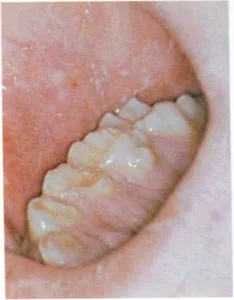

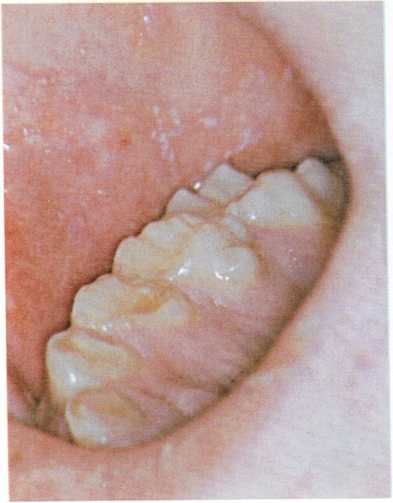

An early symptom of measles is the appearance of tiny white spots on

the insides of the cheeks, next to the molars.

ally recommend vaccination because of the complications that can follow

measles.

The first symptoms of measles are similar to those of a cold. The child

has a hard, dry cough; red and watery eyes; and a fever that may go

quite high. The fever appears about 10 days after exposure. Tiny white

spots— Koplik’s spots—appear on the insides of the cheeks next to

the lower molars two to four days after the fever. About two days later,

a blotchy red rash begins near the ears and on the neck. It spreads

rapidly down the trunk to the feet.

Call the doctor if you suspect that your child has measles. The doctor

will probably advise bed care in a partially darkened room if light

bothers the child’s eyes. The doctor will also prescribe a drug to

control the cough. The child will have no appetite while feverish, and

so the doctor will probably recommend a liquid diet.

A child who has measles can usually get out of bed in two days after the

fever is gone. About a week after the rash begins, if all the cold

symptoms are gone, the child can go outdoors and play with other

children. The disease is contagious from about

A blotchy red skin rash is the most obvious symptom of measles. It

begins at the child’s hairline and then spreads.

four to five days before the rash appears until five days after. An

attack of measles gives a child permanent immunity.

Some of the complications that may follow measles are pneumonia,

middle-ear disease, bronchitis, and encephalitis. Every child who has

not had measles should get live measles vaccine at 15 months. In the

event of exposure, babies as young as 6 months can be vaccinated, but

the child should be revaccinated at 15 months. A child not vaccinated

during infancy may be immunized at any time. If an unvaccinated child is

exposed to measles, gamma globulin may give temporary protection, or

make the disease milder, [h.d.r..] Jr.

See also Communicable diseases; Gamma globulin; Immunization;

Virus

Medicine cabinets have a dangerous fascination for young children.

To child-proof your medicine cabinet, follow these safety precautions:

- Keep all sedatives, pills, or other medicines—including aspirin

and all solutions

containing wood alcohol—locked up or out of a child’s reach.

Keep razors, nail files, and nail scissors on the more inaccessible

top shelves of the medicine cabinet. Leave the lower shelves for

cotton, bandages, gauze, adhesive tape, and other harmless supplies.Always throw away prescriptions when the illness for which they were

ordered is over. Empty all of your leftover medicines into the

toilet bowl. Rinse out the empty medicine bottles before throwing

them away in the trash containers.Every jar, box, or bottle should be labeled to show what it

contains, what the contents are for, and how they are used.Identify anything “for external use only” with a symbol marked in

nail polish.Clean out the medicine cabinet at least every three months,

discarding anything that is useless or spoiled.

A well-stocked medicine cabinet will enable you to take care of most

cuts, aches, and pains. It should contain:

Sterile gauze bandages, 3 inches (7.5 centimeters) square

Sterile bandages, 2 inches (5 centimeters) wide

Sterile bandages, 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) wide

Adhesive tape, 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) wide

Sterile absorbent cotton

Box of small prepared bandages Petroleum jelly Acetaminophen Calamine

lotion

Rubbing alcohol (70 per cent) Syrup (not fluid extract) of ipecac Rectal

thermometer

Other supplies that could be part of a household’s medical equipment are

an oral thermometer, a medicine dropper, a heating pad, an ice bag, a

hot-water bottle, tweezers, and a cold-mist humidifier,

[m.g.]

See also Accidents; Drugs; First aid; Poisonings and poisons;

Prescriptions

Meningitis is an infection of the membranes covering the brain and

spinal cord. Most cases of meningitis are caused by bacteria that are

carried by the blood to the

brain from a nose, throat, or lung infection.

In older children, meningitis often begins with a fever, irritability,

headache, nausea, and vomiting. A rash of bright red spots may also

appear. Gradually, the child’s back stiffens, and the child cannot bend

the neck forward. The child may have convulsions and may lose

consciousness.

In infants and young children, the signs of meningitis are somewhat

different. Frequently the child has no fever, and infants rarely have a

stiff neck. However, the membrane covering the fontanels (soft spots in

the skull) may stretch and become tight.

If you suspect that your child has meningitis, call your doctor. A child

with meningitis must be hospitalized in order to receive proper

examination and proper treatment. Early treatment with antibiotic drugs

is necessary to avoid serious complications or even death.

Recently a vaccine effective against Hemophilus influenzae B, the most

common cause of meningitis, has been introduced. It is, at present,

recommended that children 18 months through 5 years of age be immunized.

H.D.R., JR.