Explaining death to a child

By Stella Chess, M.D.

Even when there is no direct contact with death, it is not unusual for

children to ask, “What does it mean when you’re dead?” or, “Will I die,

too?” The children may want to know why and how a pet or a flower dies.

They may have seen a funeral procession or heard news about the death of

a well-known person.

Many parents who are willing and able to discuss almost any subject with

their children become evasive and ill at ease when questioned about

death. Perhaps it is because most of us would rather not think about

death. But death does occur. And when a loved one dies, it is especially

important that parents be prepared to talk about it. Children usually

have mixed emotions about death. They may have feelings of sorrow, fear,

resentment, and even guilt. They may become confused and bewildered. How

parents explain death, and how they answer children’s questions about

death, are important. Parents should be aware that children’s concepts

of death change as they get older.

All children do not react to death in the same way. However, research

into how children view death has shown that the following concepts are

common at specific ages.

Between 3 and 5, children tend to think of death as a kind of journey

from which a person will soon return. Or, they may think that death is a

kind of going to sleep, and then waking up. When told of a death, a

child in this age group may express sorrow\’ and then seem to forget

about it soon after- w\’ard. Parents who are unaware of this common

reaction may worry that their child is self-centered and heartless.

Between the ages of 5 and 9, most children accept the idea that death is

irreversible, but they believe that death happens only to certain people

and that it cannot happen to them. Around the ages of 9 or 10, children

begin to understand that death happens to all living things, and that

they, too, wall die eventually.

Some ways to answer questions

No matter how\’ difficult it may be for you, a direct, honest answer

about death is the best one. Evasive answers may make a child’s feelings

of grief, fear, and resentment stronger and longer lasting. Children are

not nearly as afraid of what they can understand as they are of things

that are cloaked in mystery. Even death can be less terrifying if it is

discussed openly and calmly.

In explaining death, you usually have to deal with such facts as

illness, accident, or old age. The amount of detail you include in your

explanation should relate to the child’s capacity for understanding. For

instance, if a 3-year-old wants to know why a grandparent has died, it

is usually enough to say, “She was very old and very tired.” A fl-

year-old might be told that the grandmother was very old and tired, and

that eventually everyone grows old and tired and can no longer go on

living.

Some parents evade an honest answer in the mistaken belief that they are

guarding their child against the pain that may be caused by the truth.

But a child cannot go through life constantly protected from pain and

grief. Sometimes, evasive answers may

even be dangerous. When a beloved grandfather dies, a 6-year-old might

be told that he has “gone to sleep.” But the child sees that the “sleep”

is one from which the grandfather never wakes. What will be the child’s

reaction? It may happen, and it has happened, that the child becomes

afraid to go to bed, fearing that he or she, too, will never wake up.

Even a religious explanation, which seems desirable to many adults, is

not always helpful. Few children find comfort in such explanations as

“God took him” or “He has gone to heaven to be with the angels.” Such

explanations may build feelings of resentment, fear, and even hatred

against the God who can strike without warning.

Naturally, children are more deeply affected by some deaths than they

are by others. When a playmate dies, a child needs more reassurance. The

child suddenly realizes that a person need not be old to die, and may,

therefore, feel threatened. It is important that parents answer the

child’s questions about such deaths, so that the child understands that

because someone the same age has died of an illness or an accident, it

does not mean that the child, too, will share a similar fate.

When a playmate’s father or mother dies, children are likely to think

that they might also lose a parent. Such fear can be lessened by

stressing the fact that very few young parents die. Parents might also

add that should anything happen to them, they have made arrangements for

the children to be cared for.

The death of a parent is especially difficult for a child to face. Not

only does the child suffer gi’ief but, understandably, he or she also

feels the loss of security. The child may even feel deserted. Sometimes

the surviving parent is in no condition to comfort the child, and this

may reinforce the sense of rejection.

Sometimes, in the hope that the child will feel needed and, therefore,

more secure, the child may be mistakenly told, “Now you are the man of

the family,” or “Now you must take your mother’s place.” No child, no

matter how willing, can take the place of the lost parent. Such a

responsibility should not be thrust on the child.

This is a time when an adult relative or close friend of the family can

be a source of strength by reassuring the child about the future.

Guilt feelings

Children often feel that in some way or other they may be responsible

for the death of a member of the family or a playmate. If a sick

gi’andparent has lived with the family for a while, it is quite likely

that the child was constantly “shushed” during the illness.

Understandably, the child has not always been completely quiet. This in

itself may make a child feel guilty when the grandparent dies. If the

child is overly sensitive, such feelings can be most disturbing. Should

a brother or sister die, some of the natural feelings of hostility among

brothers and sisters may haunt the child. It is as though something the

child did or thought contributed to the death. Parents can help their

child overcome such feelings of guilt if they are aware that they may

occur.

Mourning

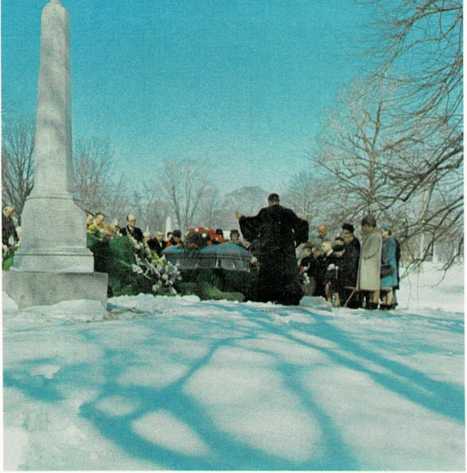

There are differences of opinion and practice about children’s

participation in family gatherings of mourning relatives and in funeral

ceremonies. A common practice in many families is to send the children

to stay with friends so that they will be spared the upsetting effects

of gi’ief. In some instances, this may be wise, but often this makes the

child feel alone and shut out. It may add to the child’s feelings of

fear. To be with the family, yet to be protected from the more extreme

demonstrations of grief, is often more reassuring for the child than

being spared the experience.

If, then, you find yourself facing the necessity of helping your child

understand a death in the family or the death of a close friend, be

honest. Help the child realize that life holds some sorrow as well as

much joy for everyone. And recognize that the child needs special love,

affection, and understanding to get through the experience in a positive

way. The value of the feeling of belonging, in sorrow as well as in joy,

cannot be overemphasized.

Parents may be called upon to face the very difficult task of explaining

death to their own dying child. This situation usually arises when their

child has a serious, chronic disease, such as cancer, which is no longer

responding to treatment. Here the parents not only must bear their own

grief over their impending loss, but comfort their child as well.

The subject of death will seldom come as a complete surprise to dying

children, and it may even be raised by the child. This is because dying

children usually have some awareness that they will die, although each

child’s understanding of death varies with age, as explained earlier.

This awareness may develop because they may not feel as well as before,

hospitalizations may be more frequent or prolonged, they may listen to

conversations between their parents and doctors, and they may detect

attitude changes on the part of their parents. Here again, no matter how

difficult it may be for you, direct, honest responses about death are

the best ones. From the onset of an illness from which death may result,

parents are encouraged to foster a loving, secure home environment in

which questions, fears, and anxieties can be voiced by their child and

discussed openly. This kind of environment sets the stage for honest,

much needed communication when the child’s death later becomes more

imminent. A child who is met instead by silence concerning the subject

of death will experience unnecessary loneliness or isolation from loved

ones, unwarranted anxieties or guilt, or the worry that he or she is

being punished.

Sometimes parents will need to bring up the topic of death themselves,

since their children may not want to upset or hurt them by voicing their

concerns. Parents’ comments should be related to the children’s capacity

for understanding. For children who are five or more years old, parents

can begin by asking whether they have thought at all about dying.

Younger children may be told that the treatments are not working

anymore, and that after dying there will be no more suffering. It should

be noted that children of all ages tend to have rather concrete worries

that include whether they will be alone or in pain when they die. It is

important that children be reassured that their physical needs will be

met in every possible way with the help of doctors and nurses, whether

they are hospitalized or at home. Most important, children will find

great comfort in their parents’ presence and expressions of love and

caring.

If the process of a child’s death can be experienced as a family with

affection, acceptance, and open communication, many parents have found,

in these difficult days, precious moments that they cherish as memories

forever.

David R. Freyer, D.O.

Consulting Editor/Contributor