Dehydratation – Dislocation

Dehydration is a condition that results when the water content of

the body drops excessively. It is sometimes accompanied by a loss of

certain body minerals, such as sodium and potassium.

Dehydration is caused by one of two things. The first is an increase in

the loss of water from a child’s body, as may occur with persistent

vomiting, persistent diarrhea, excessive sweating, high fever, severe

burns, or increased urination. The second cause of dehydration is a

decrease in the intake of water, as may occur when a child does not or

cannot drink sufficient fluids for

the body’s normal functions. Sometimes, both factors may cause

dehydration. For example, a child who is vomiting is losing water from

the body. At the same time, the child may not be able to drink any

liquids.

The severity of dehydration depends upon the amount of water and the

amount of minerals lost. Generally, the child’s skin is dry, and the

tongue and the lining of the mouth are parched. Skin may become less

elastic. Babies and young children lose weight. Occasionally, the child

may run a fever of 102° F. (39° C) or higher. In more severe cases of

dehydration, the child may be listless and the eyes may be sunken. The

soft spots (fontanels) in an infant’s head may become depressed.

If your child shows signs of dehydration, call your doctor. If you

cannot reach the doctor, take the child to a hospital. If the diarrhea,

vomiting, or other cause of the dehydration has stopped, give the child

water or cracked ice. If the child can keep this down, then give

frequent small amounts of weak tea, a mixture of half water and half

apple juice, or a carbonated soft drink. A teaspoonful at a time may be

all a small child can take.

The doctor will judge the severity of the dehydration on the basis of

what has caused it and on any signs of dehydration the child has. The

doctor may also examine samples of the child’s blood and urine to

determine if there has been a mineral loss. If the dehydration is not

severe, the doctor may advise oral rehydration. If it is severe, and

especially if there is persistent loss of fluids, the doctor will

probably advise hospitalization and giving fluids intravenously,

[m.g.]

See also Diarrhea; Fever; Soft spots; Urinary disturbances; Vomiting

Diabetes mellitus is a disease in which the body fails to utilize

sugar properly. In children with insulin-dependent Type I diabetes, the

failure generally occurs because of destruction of the cells that

produce insulin, the hormone that enables the body to store and burn

sugar in its normal manner. Diabetes is more common in adults, but it

can occur at any age.

A child with untreated diabetes usually eats a great deal more than is

normal, drinks large quantities of water, and urinates frequently or in

large amounts. A doctor can diagnose the child’s condition by analyzing

the child’s urine and blood. A child who has diabetes will show an

excess of sugar in both blood and urine. If the diagnosis is not made

promptly and treatment begun, the child loses weight rapidly, breathes

deeply and rapidly, is nauseated, vomits, gradually becomes weaker, and

may become drowsy or go into a diabetic coma.

All diabetics should be under a doctor’s care. Although diabetes cannot

be cured, it can be controlled through the use of insulin injections and

diet. Care must be taken to regulate the amount of insulin given,

because too much may lower the blood sugar to a point where the child

may feel unusually hungry or nauseated. The child may perspire and grow

pale, or faint and lose consciousness—sometimes with a convulsion.

This condition is called insulin shock. If a child appears to be

developing insulin shock, offer orange juice or some other food that

contains sugar and promptly call your doctor.

Although the diabetes will be lifelong, it should not interfere with the

child’s psychological and social development. Encourage the child to

participate in the usual childhood activities and to take care of his or

her own dietary and insulin needs. Diabetic children can grow to adult

life able to carry on normal activities, [m.g.]

See also Convulsions; Diets; Drugs; Endocrine glands; Heredity

Diaper rash is so frequent in its mild form that almost every baby

has it sometime. The skin in the diaper area looks red and chafed, and

sometimes there are a few pimples and rough red patches on it. The rash

may spread and the baby may be uncomfortable. Sores of severe diaper

rash on the circumcised penis may result in painful urination.

Severe diaper rash usually results from friction and associated contact

imtants (harsh soaps, detergents, acid stools, or topical medications).

Sweat retention with

excessive heat and moisture are other significant factors.

To treat diaper rash, change wet or soiled diapers frequently. Avoid

using waterproof pants over the diapers, especially on very young babies

or on those with sensitive skin. Rinse the diapers thoroughly after

washing them. The “rinse” cycle of an automatic washing machine usually

rinses the diapers adequately. Disposable diapers may be less irritating

and should be tried.

When your baby’s skin is chafed, let the baby lie without diapers for

several hours after each diaper change. The air will help dry and heal

the skin. Apply a protective preparation, such as zinc oxide paste or a

baby lotion, after the skin has been cleaned with plain water. Your

doctor may want to recommend a preparation.

For severe diaper rash, leave the diapers off for two to four days and

use a fan to circulate the air. If cloth diapers are being used, rinse

the diapers in a vinegar solution—use \’A cup of household vinegar in

the tub of rinse water. Rinse the diapers in this solution after they

have been completely washed and rinsed. After rinsing them in the

vinegar solution, wring the diapers out, or let them go through the

“spin” cycle of an automatic machine, and dry them in the usual way.

Occasionally, diaper rash occurs because enzyme- and bleach-containing

detergents are used in washing the diapers. You can lessen the chances

of this if you use a mild soap and rinse the diapers thoroughly.

If the diaper rash looks like a chemical burn, develops blisters, or

becomes infected, consult the baby’s doctor. Candidiasis (a fungal

infection) and impetigo (a blisterforming skin disease) are fairly

common complications of severe diaper rash. [am.m.]

See also Impetigo

Diarrhea is an intestinal disorder marked by frequent loose, watery

bowel movements. Diarrhea can be serious, especially when it is

accompanied by mucus or blood in the stools, listlessness, failure to

eat, dehydration, vomiting, or fever. If your child’s diarrhea persists

or appears to be serious, call your doctor.

Diarrhea in babies is often caused by problems in feeding. Sometimes the

baby’s formula is not sterilized adequately or is made in incorrect

proportions. Check with your doctor about your formula preparation and

the amounts you are feeding the baby. Sometimes one or two loose stools

may occur when the baby starts eating new solid foods. To help your baby

adjust more easily to new solid foods, cut down on the amount of the

foods and start any new foods slowly. Occasionally, diarrhea may be

caused by a food allergy.

Mild diarrhea may accompany a general infection. Your doctor may

precribe medicine for the general infection. The doctor may also suggest

that you give your child extra fluids (water, diluted formula, or other

liquids) to help replace the fluid lost with the diarrhea. The doctor

will probably tell you to feed the child a bland diet of such foods as

applesauce, cereal, and gelatin.

Sometimes a specific bowel infection causes diarrhea. Be careful to

prevent spreading the infection to other members of your family. Wash

your hands after handling the baby or diapers. Place the diapers in a

covered container and wash them separately from other clothing. Boil the

diapers or iron them to kill germs.

In older children, diarrhea is usually milder, but it occurs for similar

reasons— bowel infection or as part of a general illness. Diarrhea may

also be a symptom of tension or anxiety that occurs at times of stress

or excitement, such as a school examination or a special party. If these

situations frequently cause diarrhea, consider ways to relieve your

child of stress or help avoid too much excitement, [m.g.]

See also Allergy; Dehydration; Food poisoning; Influenza; Sterilizing

Diets. A balanced diet contains all the food elements that a child

needs to grow and stay healthy. A child requires proteins to build body

tissues, fats and carbohydrates for energy, and minerals and vitamins

for growth, maintaining body tissues, and regulating body functions.

Your doctor may prescribe a special diet for your child if the child has

an illness, a

metabolic disorder, a food allergy, or a weight problem. Be certain you

know why the diet is being prescribed and how you can best carry it out.

Here are some questions you may want to ask when the doctor advises a

diet:

■ Is the quantity of food eaten important? If so, how can you keep a

record of what the child eats?

■ How urgent is it to follow the diet closely? In some metabolic

diseases, where the child’s body cannot digest certain component

materials in foods, it is vitally important to follow the dietary

prescription to the letter.

Encourage your child to stay on the diet. If there are choices among

foods, use those the child prefers, especially if the child must remain

on the diet for a long time. Let the child who can understand assume

some responsibility for eating needed foods and avoiding others. Most

children are happy to have this trust placed in them. Older children

often can help plan what they will eat. Helping make such decisions may

give them the incentive to carry them out.

Make diet foods as appealing as you can. For instance, a white cream

soup, served in a colorful bowl or cup with a bright garnish, usually

perks up the appetite of a child on a bland diet.

A child on a diet has to learn to go without eating certain foods, but

try not to put an extra strain on willpower. For example, a child who is

allergic to eggs has to accept the fact that he or she cannot eat eggs

for breakfast even though the rest of the family has eggs. But serve

eggless desserts so that the child can eat the family dessert,

[m.g]

See also Allergy; Anorexia nervosa; Appetite; Nutrition: Overweight;

Underweight; Vitamins

Diphtheria is a severe, contagious disease that causes a membrane to

form in the throat or nose. This membrane may hinder breathing and

eventually cause choking or even death. Diphtheria is caused by

bacteria. Once common, diphtheria is no longer widespread because almost

all children are immunized against it.

Diphtheria usually begins from two to four days after exposure. A child

with diphtheria may have a sore throat, fever, headache,

backache, drowsiness, and vomiting. Yellowish-gray patches may appear on

the throat, the tonsils, or the roof of the mouth. Sometimes the

membrane so completely obstructs the throat that the child cannot

breathe. A doctor may have to perform a tracheotomy (incision into the

windpipe) to get air into the lungs. Call your doctor immediately if you

suspect that your child has diphtheria.

Inoculations of diphtheria toxoid are routinely given in a single shot

along with tetanus (lockjaw) toxoid and pertussis (whooping cough)

vaccine. These inoculations, called DPT shots, are usually begun when

the infant is 2 months old. The last infant DPT shot is given when the

baby is 16 to 18 months of age. As further protection, a DPT booster is

given at 4 to 6 years of age, or when a child enters kindergarten or

first grade.

For nonimmunized children over 6 years of age, two Td shots (combined

tetanus and diphtheria toxoids) are given eight weeks apart. A third

shot a year later completes the immunization.

For continued protection, all immunized children should have a Td

booster shot at 14 to 16 years and at 5- to 10-year intervals during

adult life.

A baby who has received a DPT shot may have a fever and a loss of

appetite, and will be cranky. The area around the injection may be sore

and red. This reaction occurs because of the whooping cough vaccine. To

relieve fever, give acetaminophen in doses appropriate for the baby’s

age. Your baby should feel better the next day. If your baby runs an

excessively high fever or exhibits other abnormal behavior, notify your

doctor. The doctor may wish to modify the immunization schedule,

[h.d.r„] jr.

See also Communicable diseases; Fever; Immunization; Shots; Tetanus;

Whooping cough

Disinfecting. See Sterilizing

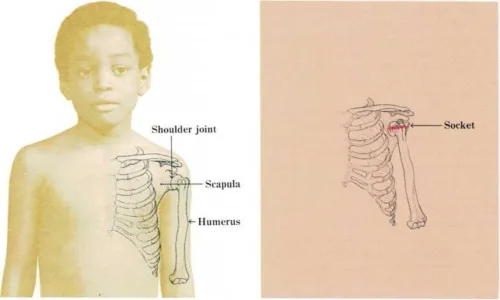

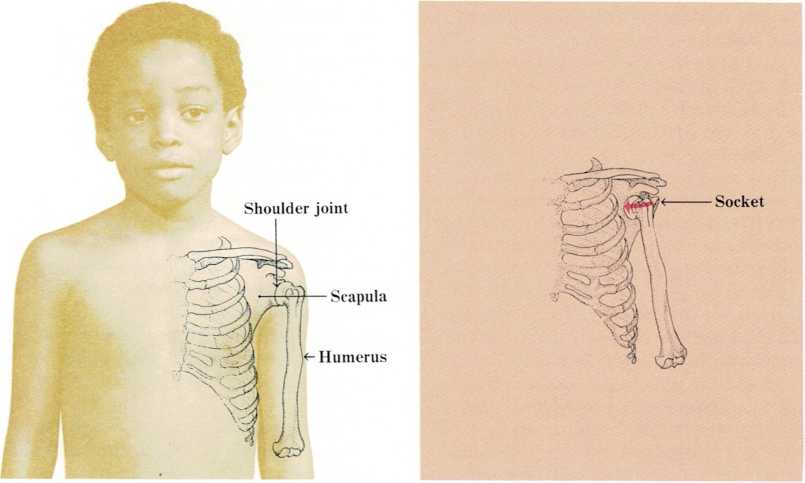

Dislocation of a joint. A joint is dislocated when the two bone ends

that make up the joint become separated and no longer work together.

Most dislocations are caused by injury. They occur most frequently in

the shoulder, elbow, ankle, or finger joints. A

The shoulder joint consists of two bones—the humerus and the

scapula. When the humerus slips out of the socket of the scapula

(right), the shoulder is dislocated and the child experiences

immediate pain.

dislocation causes immediate pain and rapid swelling of the injured

part. There is usually a visible deformity, and the joint cannot be

moved normally. In addition, one of the dislocated bones may be broken.

A joint dislocation is serious and requires immediate medical treatment.

Call a doctor at once and do not move the child. If you cannot reach a

doctor, protect the joint by putting splints on the injured part in the

most comfortable position. Never pull on the bones or attempt to

relocate the joint yourself. After applying the splint, take the child

to a hospital immediately for X-ray examination and proper care. The

child will probably be given an anesthetic, and the doctor will attempt

to gently manipulate the bones of the joint back into their proper

position. Most often this is successful. Rarely, an operation may be

needed to correct the dislocation. The doctor will usually apply a

splint, cast, or brace to protect the healing joint.

Sometimes a joint, usually the shoulder or kneecap, will dislocate

periodically. Surgery is required to correct this condition, v.v.c.

Drowning. See CPR