Deafnes

Deafness is the partial or complete inability to hear certain

sounds. More specifically, it is the inability to discriminate speech.

In a child with normal hearing, sound waves pass through the ear canal.

They strike the eardrum, a thin membrane that separates the ear canal

from a tiny chamber. The eardrum and three small bones in the chamber

are called the middle ear. When the eardrum moves, the movement is

transmitted along a chain of the bones—the hammer, the anvil, and the

stirrup—to the inner ear. There, the cochlea (an organ shaped like a

snail’s shell) changes the vibrations into nerve impulses, which are

sent along the auditory nerve to the brain. Deafness may result if

anything interferes with the healthy operation of any of these parts.

There are three main types of hearing loss. If sound waves are not

conducted ade

quately to the child’s inner ear, the hearing loss is called conductive.

If sound waves reach the child’s inner ear, but they are not properly

changed into nerve impulses, the hearing loss is called nerve deafness

or perceptive deafness. If the child’s hearing loss is the result of

both conductive and perceptive impairments, the hearing loss is called

mixed deafness.

Causes of deafness. Deafness can develop before birth. It can be

inherited. It also can develop in an unborn child if the mother has

German measles or other diseases during her pregnancy, or if she takes

certain drugs.

Or, deafness can be caused after birth by a number of illnesses or

injuries, especially head injuries such as skull fractures or

concussions. German measles, measles, meningitis, mumps, scarlet fever,

and whooping cough are some of the diseases that may cause perceptive

deafness. Infected adenoids, tonsillitis, and the common cold can cause

temporary deafness if the infection spreads to the middle ear. An

obstruction in the ear canal—an accumulation of wax, a boil, a small

object like a marble—may cause deafness. Deafness can also result if

the eardrum is ruptured by a sharp instrument, a violent noise, or

sneezing.

Detecting hearing losses. These signs can warn parents that their

child may be deaf: ■ From birth to 6 months—The child is not startled

by noises and is not responsive to pleasant or cross voices. The infant

does not turn toward the source of familiar sounds. ■ From 6 months to

18 months—The child does not understand words. The baby babbles a few

sounds, but does not turn the head in response to sounds.

- From 18 months onward—The child does not speak words but makes

wishes known by gesturing. The child does not identify objects when

they are named. The child depends on sight more than on hearing.

If you have any doubt about your child’s ability to hear, consult your

doctor. The doctor may recommend that you take the child to an otologist

(a doctor specializing in ear conditions) for examination.

Various tests can be made to determine the severity of hearing loss.

These tests include the use of the voice, a watch, tuning forks, and an

audiometer (an electronic de-

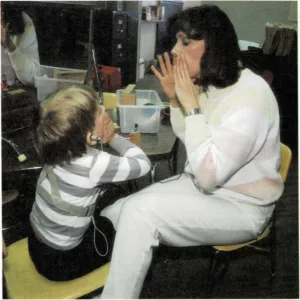

A child who is hard of hearing usually needs special speech

lessons.

vice that measures the range of a child’s hearing, from the lowest sound

to the highest). An audiometric examination helps a doctor determine

whether a child is deaf, how much hearing the child has, the character

of the hearing loss, and whether a hearing aid will be helpful.

Audiometric graphs or records also provide a means of measuring hearing

loss for a particular child over a long period of time. A record of

hearing loss can be kept and compared with new records, enabling the

doctor to tell whether the child’s hearing is unchanged, improving, or

becoming worse.

Deafness and speech. Detecting a hearing loss is important at any

age, but it is especially important in babies because speech normally

develops from hearing. A child who is born totally deaf cannot learn to

talk without special training. Early intervention is important. Families

of children as young as 6 months can participate in a

language-stimulation, auditory training program with their child, and

amplification—the use of a hearing aid—should begin before the child

is 2. The child usually enters a school when about 4 or 5 years old.

Some schools also have parent education programs to help parents

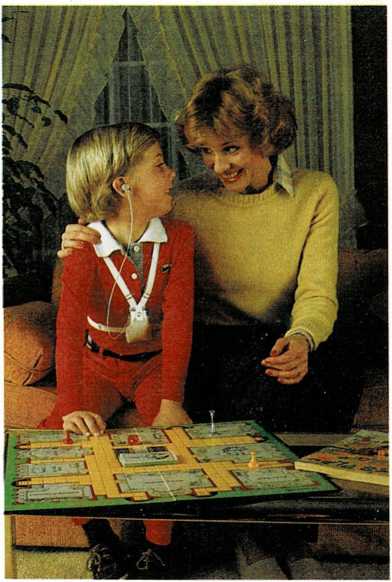

A hearing aid does not restore hearing to a hearing impaired child,

but it does amplify the sound so that the child can hear the sounds

and discriminate between different sounds.

guide their child even before the child enters school. Excellent parent

education programs are also available by mail. (See [Agencies

and] ORGANIZATIONS INTERESTED IN THE WELFARE OF

[children.)]{.smallcaps}l schooling and guidance, a totally

deaf child can grow into a mature, self-supporting person.

Children with only partial loss of hearing usually need special speech

lessons, too. They cannot discriminate all the sounds in words and,

consequently, cannot reproduce the sounds adequately.

Hearing aids. A hearing aid consists essentially of a microphone, an

amplifier (also called a transmitter), and a receiver. The microphone

picks up sound, and the amplifier makes it louder and transmits it to

the receiver by means of a wire. The receiver is small and usually made

to fit in the child’s ear. Some amplifiers are made to be worn on

a jacket lapel or some other place where they can receive sound freely.

Others are small and are worn as part of an ear-level hearing aid.

There are two types of hearing aids—the air conduction aid and the

bone conduction aid. An air conduction aid amplifies sound, transmitting

it directly to the ear. Bone conduction aids transmit sound waves to the

bony part of the head, usually in the mastoid region behind the ear. The

air conduction aid is by far the more popular and usually the more

effective, but the bone conduction aid may be better for some children.

A hearing aid will not restore or bring hearing to normal, but it will

amplify sound so that it can be heard and so that the child can be

taught to discriminate sounds. Many of the sounds will seem new or

strange at first. Voices may sound different because they lack some of

the qualities and timbre of normal speech. This is especially true if

the child had normal hearing at one time and then lost it, either

through disease or injury.

A child with partial deafness can frequently hear some tones better than

others. The hearing aid can be adjusted to amplify tones the child has

difficulty hearing. Hearing aids also help a child hear sounds in the

immediate surroundings, such as approaching cars.

An ear specialist will tell you whether a hearing aid will help your

child. The doctor can also tell you whether the child will benefit most

by using a hearing aid at all times or only when it will help

most—during school, for example, [c.f.f.]