Common concerns

During the early school years, children are presented with a new social

environment and social challenges unlike any they have had before. At

home they were usually in an atmosphere in which it was taken for

granted that they belonged and were accepted. This gave them a natural

security. Certainly at home, children have had to adapt to parents and

brothers and sisters. But the home atmosphere is unlike the challenge

and interaction provided by contact with 25 or 30 classmates. Because of

these new conditions, differences related to sex and age may become

apparent and certain problems may appear in the children’s lives.

Sex differences

Girls, when they start school, appear more mature than boys—and they

are, because they have a more rapid maturation rate than boys do during

these years. Physically and emotionally, girls are more apt to become

organized and ready to work with symbolic and abstract tasks sooner than

boys.

Patty can print her name correctly when she enters kindergarten, while

Peter, who is the same age, may only recognize the first letter of his

name. This does not mean that Patty is the brighter of the two. It may

mean merely that someone took the time to teach her what she knows and

that she may have been eager to learn this. Peter, on the other hand,

may already know about many other things. Having classmates who can

print their names and a teacher who can be helpful may encourage him to

learn. It may

also encourage him to share his knowledge with others.

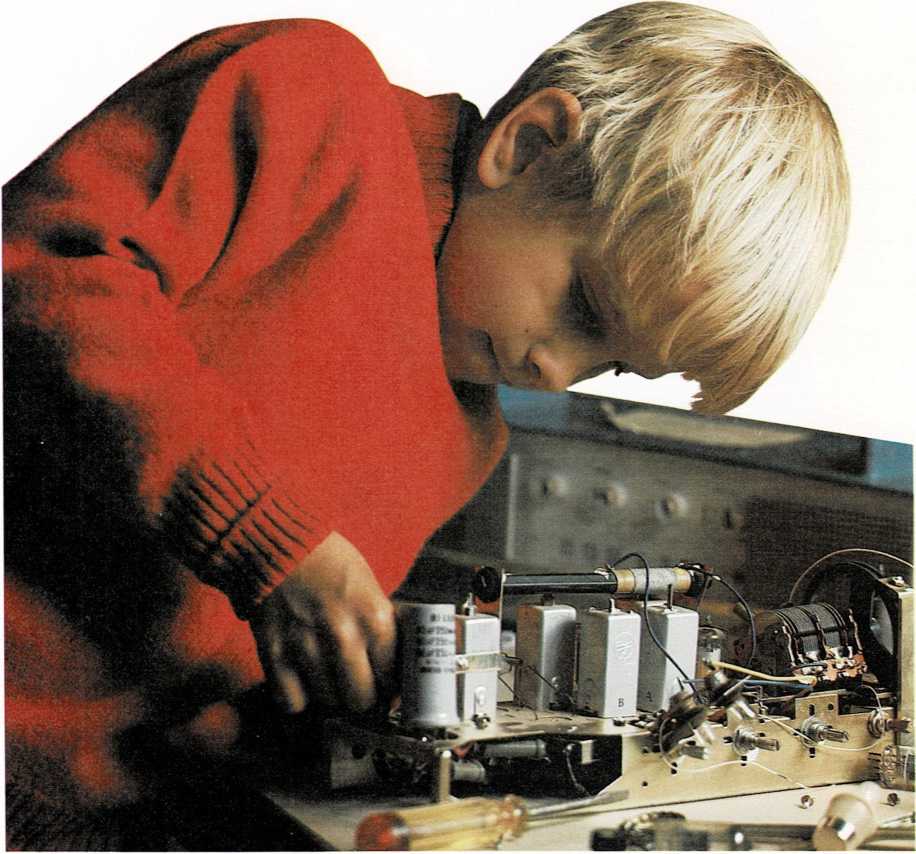

Boys do indeed have much intellectual curiosity, but they more often

focus their curiosity on physical, biological, and mechanical areas.

They like to take things apart— like flashlights, old clocks, old

radios—to find out what the component parts are and how they work.

They discover and explore things by poking around. They are liable to

walk in the kitchen with wet feet and ask the question, “Where does the

water go after it goes down the sewer?”

This is. not to say girls do not show these interests. Many do. And many

go on to become scientists.

Age differences

No matter how bright children may be, it may make an immense difference

whether they have lived less than five years or almost six years when

they enter kindergarten. Younger children are less mature than their

classmates and less experienced. They are often—though not always—at

a disadvantage.

Suppose September 1 is the cutoff date for kindergarten entrance in a

school district. This means that a child who became 5 years old on

September 2 of the previous school year is in the same class with the

child who will be 5 on September 1 of the current year. The child

entering kindergarten at nearly six years has a decided advantage over a

classmate at five years. The older child is better coordinated, more

able to

Age differences may lead to problems in social

adjustment as well as learning problems.

control impulses, and more able to concentrate on a learning task. If

the younger child is a boy, he may find it doubly hard to compete with

his classmates.

Regardless of intellectual ability, many kindergarten children cannot

bridge the age-maturity gap between themselves and their older, more

mature classmates. They may also have difficulty conforming to the

arbitrary learning timetable of many schools. The real test comes in

first grade, when most schools require children to begin reading. As one

boy sadly commented, “I always get a stomachache before I go to school.

I go anyhow and I feel sicker because I don’t catch on. And everybody

knows I don’t catch on. It’s no fun.”

The younger kindergarten child should be closely observed for the

development of social and other school-related readiness

skills. A delay in the acquisition of these skills may be due to

immaturity, and a developmental evaluation should be considered.

Masculinity, femininity

This is the age when a problem with sex identification may become

evident in a child. The child, especially a boy, may be ridiculed by his

classmates. The child may also appear to be confused and pained among

classmates, even at the kindergarten or first-grade level.

Do not leap to the conclusion that a child has a problem in sex

identification because of a few surface traits or activities—merely

because a girl is skilled in athletics, for example, or because a boy

helps his mother dust furniture. However, if a girl deeply resents being

a girl or if a boy deeply resents being a boy, a problem may exist.

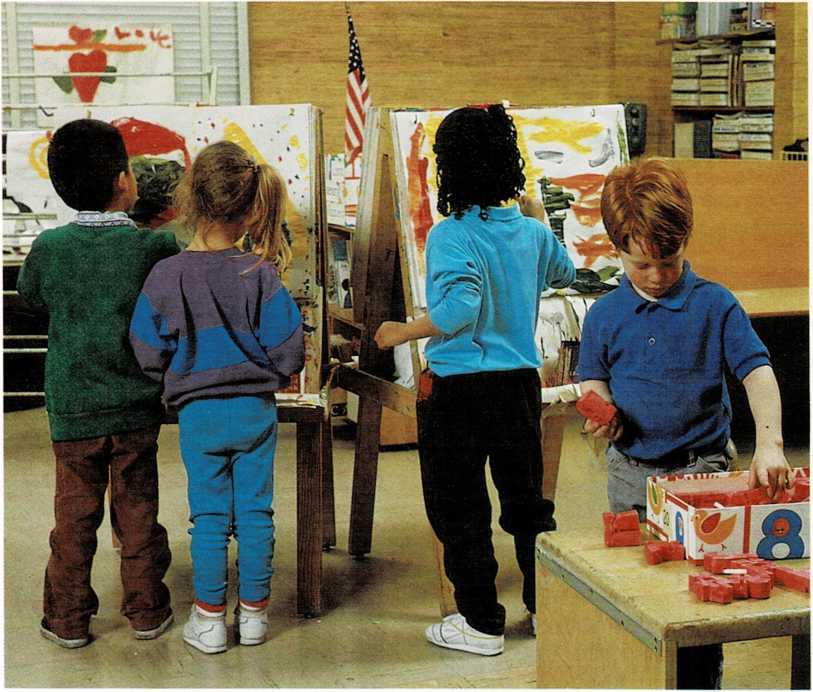

School-age children enjoy all kinds of boisterous, bustling

activities.

If a problem in sex identification is handled during these

kindergarten-primary years, chances of improvement are far greater than

if parents wait. When the child’s problem is viewed as something that

will be “outgrown,” difficulties multiply and eventually the child

becomes enmeshed in the web of added preadolescent and adolescent

problems. The original problem is then

submerged, and the child’s life may become increasingly bewildering and

lonely. If parents believe that their child has a problem in sex

identification, they should seek professional help from a psychologist

or child psychiatrist. The child’s doctor or teacher may be able to

provide the names of agencies and specialists who can help the child and

parents.

Some boys meet with academic failure in the primary grades because

they are more interested in such things as dismantling a radio or

taking apart a flashlight.

School problems

School is such an important part of a child’s life that all youngsters

face some problems in the many years that they spend there. Therefore,

parents and teachers must stay in close communication.

Problems that have their origin in school may show up only at home. For

example, a youngster who operates under tension all day long at school

may seem like an earnest, conscientious child to the teacher. The

parents may be the only ones to see the outbursts that reflect the

strain the child is feeling. Similarly, a youngster may appear at home

to be working smoothly. The teacher, watching the child in a different

setting and in comparison with other children the same age, may be the

one who first becomes aware that a problem exists. The parents and the

teacher must have some means of sharing their insights, so that any

problems can be spotted before they become too severe, and solutions can

be developed.

Unwillingness to go to school

The first sign of a school problem may be a child’s unwillingness to go

to school. Some kindergarten and first-grade children show their fear of

school openly. They cry, say that they hate school, and are unwilling to

leave home. Sometimes unwillingness to go to school shows in disguised

form through frequent complaints of illness or through prolonged

dawdling and other delaying tactics. A fear or dislike of school can be

a troubling problem. All the “legal” arguments parents are apt to use

carry little weight in a young child’s mind.

There are, of course, no pat solutions to this or any other problem. The

causes can be many, and they vary from child to child. The only good

solution is the one that gets to the root of the difficulty with

individual children. Some youngsters may hesitate because they have not

had sufficient experience in being away from home; others because the

group at school is too large for them to cope with; others because they

have specific fears, such as the school toilet or the bus ride. This

unwillingness can also be a sign that a child is experiencing learning

difficulties.

When parents and teachers begin to talk together and pool their

information, they usually can uncover the difficulties and make plans

that help children identify the problems, cope with them, and possibly

solve them. The parents’ attitudes are important while this search is

going on. On the one hand, they must feel sympathetic to children who

have problems. Life can be uncomfortable when something is going wrong.

On the other hand, parents must have a broad, basic confidence that

problems can be solved, and must communicate it. The steady sureness

that solutions will be found and that life can go on is often one of the

most helpful ways of building self-confidence and security in children.

Problems related to success ■ and failure

As children move further into their school careers, more difficulties

are apt to stem from their successes and failures in academic work, and

from relationships with classmates and teacher. Children are like the

rest of us. They cannot go through day after day of failure, of not

liking their assigned tasks, and of not enjoying people with whom they

associate, without feeling some dissatisfaction. Adults change their

jobs when they feel this way. Children cannot leave school physically.

Their only alternative is to leave mentally—to daydream, to give up in

despair, to become rebellious.

Again, there is no single answer to every child’s trouble. A patient,

mutual search by parents and teacher is the only wise procedure. A

physical difficulty, with vision or hearing in particular, may be the

cause in some cases. Academic work puts the first great strain on

hearing and vision. A complete physical examination is often a wise

first step in seeking solutions.

Children, of course, vary greatly in their ability to do schoolwork.

They vary in their native intelligence, in their growth rate, and in

their ability to handle specific kinds of subject matter. There is

always the possibility that, without meaning to, either parents at home

or teachers at school may be asking more of the children than they are

able to do. When goals and expectations are set too high, children

almost always do not succeed

as well as they could. The school administration’s solution is sometimes

to readjust its program, aiming more realistically at goals that

youngsters can achieve. Sometimes parents must make the adjustment in

their expectations at home so that their children feel that they are

good human beings and not constant failures.

Some youngsters face a problem because they are “underachievers.” They

have considerably more ability than they use. They glide through their

days, operating on only a small part of their ability. On the face of

it, this may seem not like a problem but a joy. However, youngsters are

much more contented when they work up to their ability. Unchallenged,

these children can move quite easily into various forms of misbehavior

that reflect their discontent.

It is easier to overlook children who are underachieving than the child

who daily meets failure. Failing children quickly call themselves to

adult attention. Underachievers can slide by unnoticed. Parents and

teachers need not search for problems that do not exist, but it is

important for both to talk together so that real problems are not

ignored. A parent’s account, for example, of a child’s unusual

persistence and success with a hobby or an out-of-school activity may be

the tipoff to a teacher that the youngster has more ability than the

school has tapped.

Family problems and school

The demands of schoolwork sometimes uncover tension youngsters are

feeling in their out-of-school lives. Children who worry about their

place in the family, or about their relations with their brothers and

sisters, cannot concentrate and meet the rigors of academic work. These

difficulties may well have gone unnoticed during the children’s simpler,

less demanding years before school. Many school systems have

psychologists who are trained to spot and treat such problems. Many

communities have child guidance centers or family service societies that

can help with these problems.

Social problems

School, of course, is not all academic work. A school is a social

center, too. Conflicts and achievements in getting along with classmates

take place daily. A child’s social acceptance or rejection is important

in itself and often has repercussions on how well the child learns. The

lonely child frequently adds academic difficulties to other miseries.

Problems in a child’s social life are perhaps the hardest of all for

adults to solve. Adults cannot force one child to like another. But they

can sometimes help a child to be more likable. Teaching the isolated

child some skills that other youngsters value is one useful approach.

Inviting classmates home after school is another way. Teachers can use

seating arrangements or school activities to help bring together

children who may learn to like each other.

Solutions to school problems

Parents and teachers both must realize that it takes time, patience, and

wisdom to solve all human problems. It is so easy to believe that there

are quick solutions—the teacher should assign more work in school; the

parents should take away privileges until a child’s work improves. In

individual instances these may be useful approaches, but they are not

cures in every case. In some instances, a final cure may take a long

time to achieve. Some of the factors that can be involved—for example,

large class size, a teacher’s long-established way of teaching, or a

home’s way of treating a child—do not lend themselves to modification

overnight.

Parents and teachers both must feel good will and be patient in working

together if answers are to be found. No one wants a child to face a

problem needlessly. Everyone wants the best for a child. But school and

family life both center around humans, and humans change slowly. It is

important to recognize, too, that there are some problems children have

to solve themselves. There are other problems that have no solutions,

but children can be taught to live with them and even gain strength from

the experience.