Appendicitis – Asthma

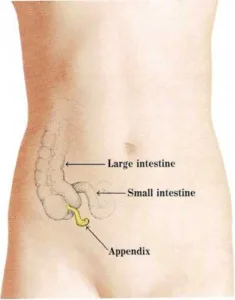

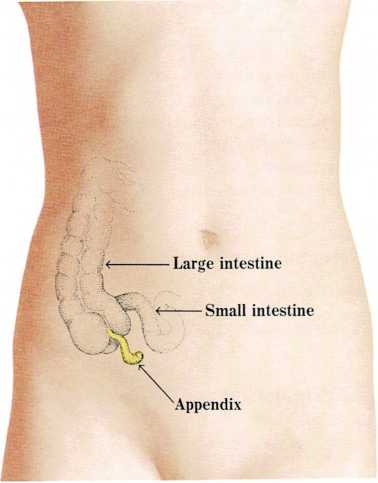

Appendicitis is an inflammation of the appendix, a narrow tube in

the lower right part of the abdomen. One end of the tube is closed. The

open end of the tube is attached to the large intestine. If the appendix

be-

Location of the appendix

The appendix is a small sac in the lower right abdomen. One end of the

appendix is attached to the large intestine.

comes infected, it becomes inflamed. It swells and fills with pus. If

there is a delay in diagnosis and surgery is not done, the appendix may

burst and cause peritonitis, an inflammation in the abdominal cavity.

Appendicitis occurs most commonly in school-age children and young

adults, but it can occur in younger children, too.

Acute (sudden and severe) appendicitis usually begins with vague,

general abdominal pain which may localize within hours to the right

lower abdomen. The abdomen may become tender. The child may vomit, have

fever, and feel constipated. Laxatives may increase the dangers of

appendicitis. Never give laxatives or cathartics (such as Epsom salts or

castor oil) for abdominal pain unless advised to do so by a doctor.

Children complain of abdominal pain often, but the pain is usually

caused by something other than appendicitis. It is important that you

contact the doctor if your child is ill with abdominal pain. Delay in

diagnosing appendicitis leads to a longer illness. Doctors estimate that

about one-third of the small children with appendicitis have ruptured

appendixes before they reach a hospital.

A child who has an unruptured appendix removed usually stays in the

hospital for 3 to 5 days. Normally, the child can return to school 7 to

10 days after the operation. A child who has a ruptured appendix removed

stays in the hospital about 10 days. Normally the child can return to

school a week or two after coming home.

See also Laxatives; Stomachache

Appetite. Whether a child has a good or poor appetite depends mainly

on the child’s age and health and the emotional climate of the home. Of

course, appetite may be temporarily affected by an illness, such as a

cold or chicken pox, or by an emotional upset. Babies experience hunger

pains when they need food. When they eat, the hunger pains stop, so

babies’ first reactions to food are pleasant. Gradually, they recognize

their mothers as givers of food. If their mothers are loving and tender

when they feed their babies, the babies begin to associate food with

love. But if the mothers fail to feed their babies when they are hungry,

appear uninterested in their babies, or force the babies to eat when

they are not hungry, the babies may have mixed feelings.

How can you promote good appetite?

Give food only to satisfy your child’s appetite. Do not force the

child to eat, and do not use food (especially sweets) as reward and

punishment.Respect your baby’s appetite as the best indicator of how much food

the infant needs. For several months after the first birthday,

children generally need less and eat less food. Parents often think

their children are not eating enough because they are no longer

growing at a tremendous rate. However, parents are usually surprised

to discover that their children are gaining weight. ■ Respect your

baby’s continuing development in feeding practices. Parents should

let babies feed themselves when they want to, even though the

youngsters may be messy for a time.

“`{=html}

“`

As your child gets older, do not let the child drink milk at the

expense of other foods. Once cow’s milk is started, limit

consumption to 3 glasses per day.Give your child finger foods. Small children like foods that they

can handle easily— foods that they can eat with their fingers and

foods that are cut into bite-sized pieces.Present new foods in small quantities. And be patient. It may take

several times before a child gets used to the new food.Remember, mealtimes should be happy occasions, free of struggle,

[m.g.]

See also Nutrition; Vitamins

Arthritis is an inflammation of body joints. A joint may swell and

become painful, and the skin covering the joint may be red and feel

warm. The joint becomes stiff and its movement limited. Arthritis can

result from injury or infection. Usually, its exact cause is unknown. If

you suspect that your child has arthritis, consult your doctor.

Rheumatoid arthritis is a common form of arthritis in children,

especially children between the ages of 2 and 6. Doctors do not yet know

what causes rheumatoid arthritis. Usually, only one or two joints, such

as the knee or ankle, are affected. However, the disease may affect many

joints. The joints can become dislocated, deformed, or fused. A high

fever is also a common characteristic of the condition. Rheumatoid

arthritis usually lasts for several years. Your doctor may prescribe

drugs to reduce inflammation and relieve pain, and may also suggest

exercises that concentrate on using the joints afflicted by arthritis.

Infectious arthritis, which also affects children, usually follows an

infection somewhere in the body, often in the upper respiratory tract.

Bacteria cause pus to form in joint cavities. Usually, only one or two

of the larger joints, such as the hip, shoulder, or knee, are affected.

The child may also have fever and chills. Doctors treat this condition

with antibiotic drugs and by draining the pus from the affected joint.

Rheumatic fever is a serious childhood disease that may cause temporary

arthritis. This form of arthritis is not connected with rheumatoid

arthritis. Usually, the larger joints, such as the ankles, knees, hips,

wrists, elbows, and shoulders, are affected. The arthritis tends to move

from one joint to another, with any one joint being affected

from a few days to several weeks. This type of arthritis is generally

treated with drugs to relieve pain and reduce inflammation.

Other forms of temporary arthritis may also affect children. For

example, a child may injure a joint—most commonly a knee joint—and

develop arthritis in that joint. Occasionally, a young child develops a

brief episode of arthritis of the hip from an unknown cause,

[m.g.]

See also Osteomyelitis; Rheumatic fever

Artificial respiration. See CPR

Asphyxiation. See Suffocation

Aspirin poisoning. See Poisonings and poisons

Asthma is an allergic disease that affects the bronchial tubes. It

causes coughing, wheezing, and labored breathing. Breathing is

obstructed by the swelling of the mucous membranes of the bronchial

passages, by muscle spasms in the walls of the bronchial tubes, and by

the excessive secretion of a thick, sticky mucus. The onset of asthma

may be abrupt or gradual. An attack may be mild, or it may require

hospitalization.

Childhood asthma is usually caused by respiratory infections or by

inhalants (substances that float in the air, such as house dust, molds,

pollen, and animal dander, i.e., particles from animal skin, hair, and

feathers). House dust mites eat dander, molds, and natural fibers and,

after a few days, die, leaving excrement, carcasses, and baby mites, all

of which may trigger asthma. Less often, emotional problems or foods may

bring on or aggravate an asthmatic attack. Air pollutants, low

barometric pressure, humidity, changes in temperature, and other factors

may also provoke asthma.

Any child with asthma should be under a doctor’s care. Asthma rarely

improves without treatment from a doctor. If asthma is neglected, it

often recurs for many years, and it may permanently change the child’s

lungs and chest wall.

In treating asthma, the doctor tries to determine the substance or

substances causing the attack. The doctor will want to know if the child

has had previous or associated allergies, and know about other family

members with asthma or other allergic diseases, since these tend to run

in families. The doctor will also want to know the frequency of the

asthma attacks, foods the child eats, pets the child is exposed to, and

other details of the child’s life—for example, does exercise or cold

air cause the child to wheeze? The doctor may perform prick tests or

intradermal tests to determine what airborne substances the child is

sensitive to.

Drugs may be prescribed to widen the bronchial tubes by relieving

bronchial spasms and shrinking the mucous membranes. Breathing and

physical fitness exercises may be prescribed. The doctor will probably

suggest eliminating pets, house dust, feathers, cigarette smoke, and

other substances from the child’s surroundings. Immunization to build up

a child’s resistance to airborne substances is also helpful,

[j.sh]