Drum talk

“Listen!”

The two men stopped, every sense alert to the world around them. The

air was filled with sound—birds screeching, monkeys chattering. But

that was as it should be. The jungle is always full of noise. There

were no strange sounds.Then they heard it. The high and low notes of a drum. The sound could

be heard clearly above the din of the jungle. They listened carefully

as the drumbeats

continued. Then, as suddenly as it had started, the drum stopped.

One man turned to the other. “Come,” he said, “we are needed at the

village.”

How did they know they were needed? They had heard the message on the

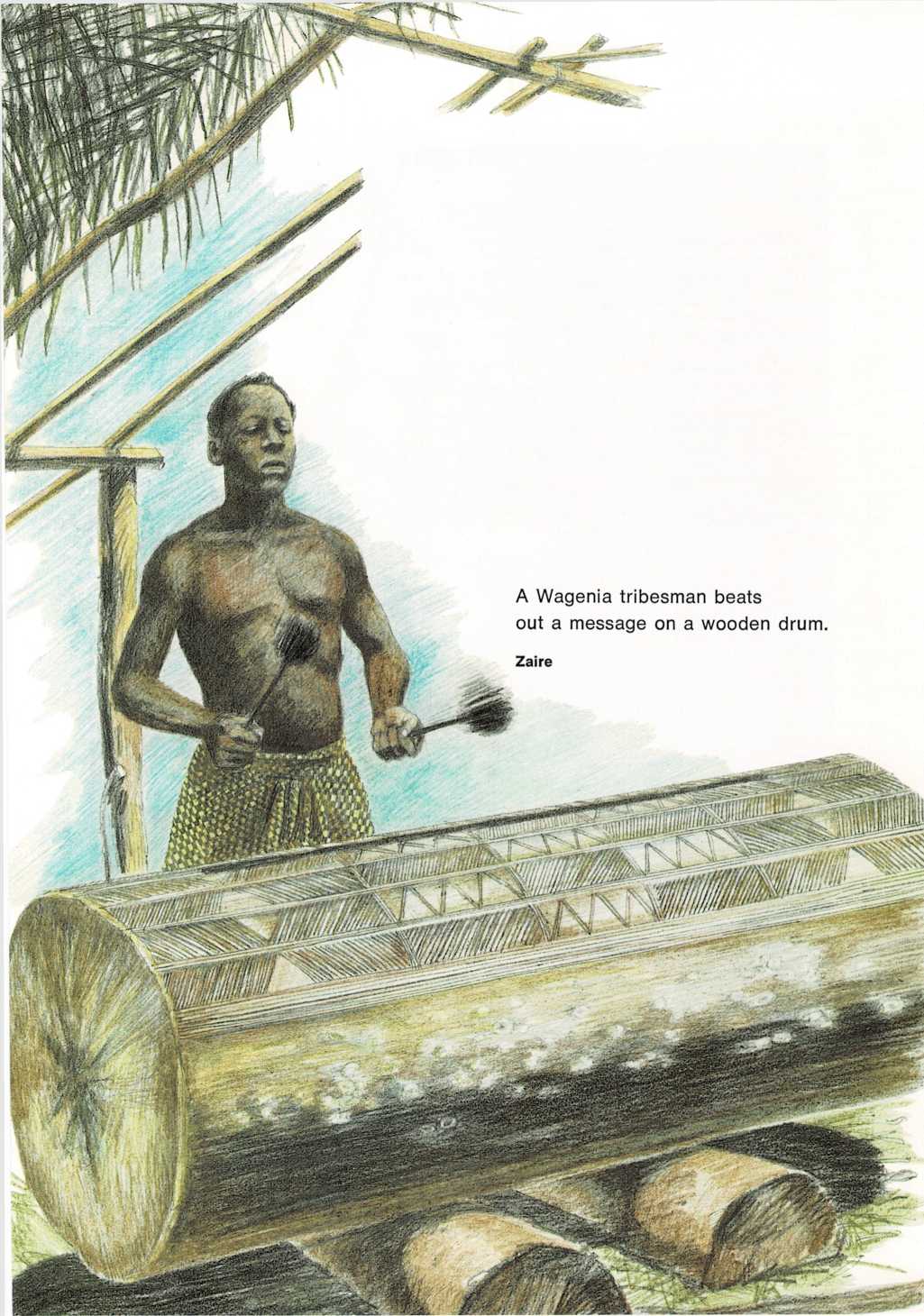

“jungle telegraph.” In Zaire, Congo, and other countries in Africa,

drums—or gongs, as they are called in Congo—are still used to send

messages.

A gong is a big, hollow log with a long slot in it. Beaten on one side

of the slot, it makes a low note. Beaten on the other side, it makes a

high note. These two notes are like the high and low tones of the

language.

To make a message clear, many words are often needed. It may take as

many as 14 drumbeats to send one short word such as “dog.” All messages

are sent twice.

Every village has a gong. And every gong has a name. The name is beaten

out at the beginning or end of the message. The gong at Yatuka village,

in Congo, is called “Masters of the river.” A nearby gong is named “The

evil spirit has no friend or kin.” The people of Yangomu village named

their gong “Birds do not steal from a person without food.”

A gong can be heard 2 to 10 miles away. But if you want to talk to

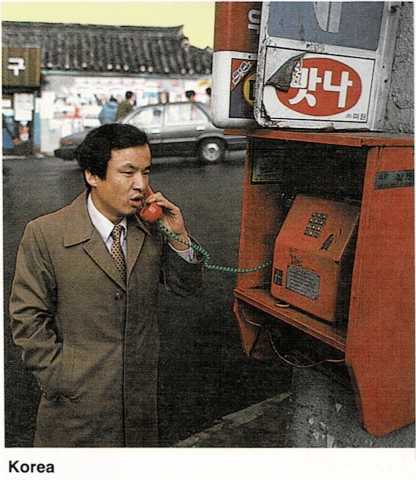

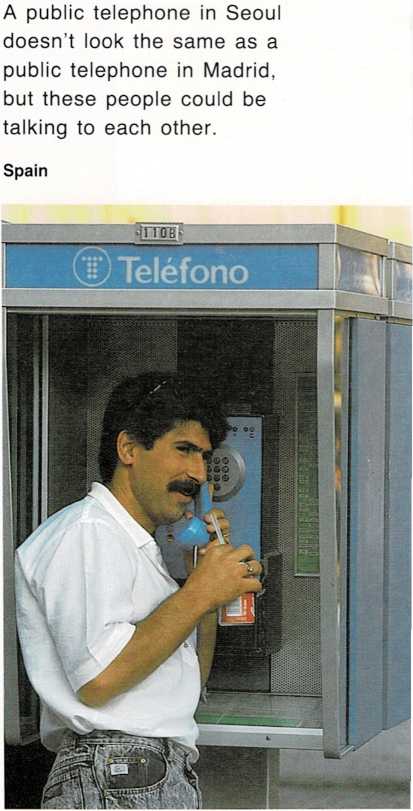

someone on the other side of the world, you’ll have to use a telephone.