CPR – Croup

CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) is an emergency procedure that

combines artificial respiration with manual heart (cardiac) massage.

Instructions for both parts of the procedure are provided in this

article.

CPR is used to open the passage from the lungs to the mouth, to move air

in and out of the lungs by making the chest alternately expand and

contract, and to force blood from the heart to other parts of the body

by compressing the heart periodically. Using this procedure can prevent

irreversible brain damage or death if the breathing and heartbeat have

stopped.

If possible, CPR should be performed by someone who has been trained in

the technique. Training is often available through community agencies.

If you have not had CPR training yourself, the following explanation

will help you become familiar with the procedure.

CPR is also more easily performed by two people. If possible, have one

person administer artificial respiration and the other person perform

cardiac massage.

When a child’s breathing stops for any

reason, quickly begin artificial respiration and check the child’s

pulse. If no pulse can be felt, apply CPR immediately (both artificial

respiration and heart massage) while someone else calls the Emergency

Medical Services (usually 911; check your local emergency number).

If the child’s breathing has stopped because of drowning, lay the child

stomach down on a flat surface, turn the child’s head to one side, and

press down on the back before you start CPR. This clears water from the

child’s throat and trachea (windpipe) so air can pass freely.

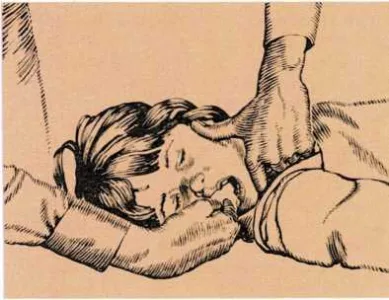

Turn the child faceup, turn the head to one side, and clear the mouth of

any foreign object. Then put your hand under the child’s neck and tilt

the head back.

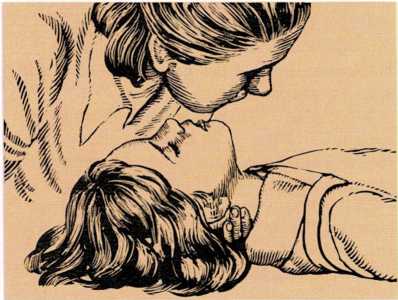

Artificial respiration. Begin CPR with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

This provides positive air pressure to inflate a child’s lungs

immediately. It also enables the person administering CPR to judge the

volume, pressure, and timing needed to inflate the lungs. When

administering mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to a child, take relatively

shallow breaths to match the child’s own small breaths. Continue until

the child’s normal breathing resumes or until professional help arrives.

When handling an infant, be careful that you do not exaggerate the

backward position of the head tilt. An infant’s neck is so pliable that

forceful backward tilting might block the child’s breathing passages

instead of opening them.

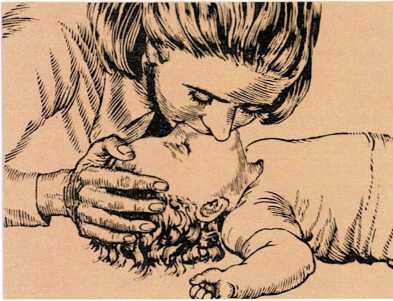

Do not pinch the nose of an infant who is not breathing. Cover both the

mouth and the nose with your mouth and breathe slowly (1 to 1.3 seconds

between breaths) to make the chest rise. For a small child, pinch the

nose, cover the mouth with your mouth, and breathe as for an infant.

Check for pulse periodically. In an infant, the pulse is determined by

feeling on the inside of the upper arm midway between the elbow and the

shoulder. For children older than 1 year, locate the carotid pulse by

sliding your fingertips down the side of the Adam’s apple (voice box)

into the groove next to it. If you cannot find a pulse, you will need to

alternate artificial respiration with chest compressions.

How to give mouth-to-mouth artificial respiration

1. The victim should be lying on a firm surface with the head turned

to one side. Use your fingers to remove any foreign object from the

child’s mouth.

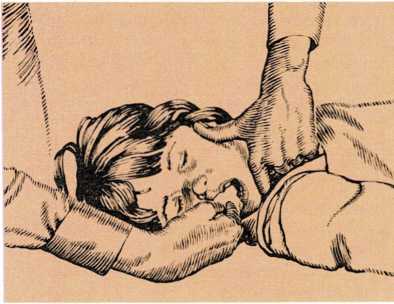

2. Place one hand under the victim’s neck and the other hand on the

forehead. Then tilt the head back. If the head is not tilted back, the

tongue may block the throat.

3. If the victim is a small child or infant, take a shallow breath.

Cover both the nose and mouth of the victim with your mouth. Blow into

the mouth and nose every three seconds.

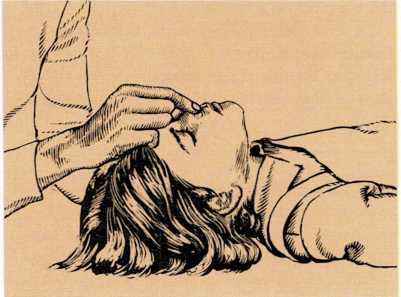

4. If the victim is a large child or adult, pinch the nostrils shut

with the thumb and index finger of the hand pressing on the forehead.

This will prevent any leakage of air.

5. Take a deep breath and cover the victim’s mouth with your mouth.

Blow into the victim’s mouth. A large child or adult needs about one

breath every five seconds.

6. Watch the victim’s chest. When it rises, turn your head and

listen for a return rush of air. When the victim has finished

breathing out, repeat step 3, or steps 4 and 5.

Cardiac massage. In infants and small children, only one hand is

used for chest compressions. For an infant, you may slip the other hand

under the back to provide firm support. Use only the tips of the index

and middle fingers to compress an infant’s chest at the sternum

(breastbone), pressing down one finger’s width below the line between

the nipples. Be sure not to depress the tip of the sternum. Depress the

chest at least 100 times a minute.

For small children, use only the heel of one hand on the sternum where

the bottom of the two halves of the ribcage meet in the middle of the

chest. Depress the sternum 80 to 100 times a minute.

For both infants and small children, pause after every fifth chest

compression and give the child a breath.

Cradle cap is a scalp condition that may occur during the first few

months of a baby’s life. Whitish scales form on the baby’s scalp and

then flake off. If the condition is not treated, the scales form a

heavier crust that is yellowish and greasy. When cradle cap reaches this

stage, the scalp may look a little red and irritated, and a rash may

develop on the baby’s face and chest, and in the armpits.

The best way to prevent cradle cap is to shampoo the baby’s scalp

thoroughly (including the soft spots) at the beginning of each bath. Use

soap and water and a washcloth.

If your baby has already developed cradle cap, repeat the following

steps once or twice a day:

Comb the scalp with a fine-toothed comb.

Gently scrub the scalp with a mild soap. ■ Dry the scalp thoroughly.

Apply several drops of baby oil to the scalp and rub it in

thoroughly.

If the condition does not improve in a few days, consult the baby’s

doctor, [a.m.m.]

Cramp is the sudden painful contraction of a muscle or group of

muscles. A cramp is caused by some unusual event irritating

muscle tissue. Although cramps may occur in any part of the body, leg

and stomach cramps are the most common.

Leg cramps usually occur at night, after the child goes to bed. The

child may be awakened by painful cramps in the calf and thigh muscles.

You can usually relieve the pain by massaging the cramped muscles.

Muscle cramping may be caused by sudden overstretching or overactivity

of muscles. The most common cause of muscular leg cramps in a child,

however, is flat feet. The abnormal arch of the foot strains the leg

muscles, and they develop cramps during rest periods. Consult your

doctor if your child has leg cramps frequently.

Abdominal and intestinal cramps may occur in girls during the menstrual

period. Applying heat and using acetaminophen may help relieve pain.

Abdominal and intestinal cramps may also be caused by appendicitis, an

ulcer, food poisoning, or emotional upset. If the cramps last longer

than 24 hours or are accompanied by severe vomiting, call the doctor,

[jj.c.]

See also Charley horse; Colic; Colitis; Elat feet; Food poisoning;

Growing pains; Menstruation

Crib death (Sudden Infant Death Syndrome or SIDS) is the sudden and

unexpected death of an infant, usually while asleep. Ongoing research

has not yet established the cause or causes of death. It is estimated

that more than 8,000 babies die in the United States each year because

of crib death.

Some stricken infants are reported to have had a mild respiratory

infection a week or two earlier. But most infants are apparently in

excellent health just before death. Some even had a satisfactory

physical examination on the day they died.

Crib death is the most frequent cause of death in infants between 2

weeks and 9 months of age, with most deaths occurring between 2 and 3

months of age. Most deaths occur between midnight and 9 A.M. Boys are

affected more often than girls, and infants of low birth weight are more

likely to be affected than those of average or high

birth weight. While crib deaths may occur at any time during the year,

they are more frequent in colder months.

Parents who have had a baby die from crib death often feel responsible

for the death. Their guilt feelings, while natural, are not supported by

facts. There is no way in which crib deaths can be predicted or

prevented. These infants do not suffocate in their bedclothing. And they

do not die because of poor care. Crib deaths can occur to infants of the

most capable parents.

Parents who have had one child die from crib death usually worry about

the possibility of a second baby dying in the same manner. There is an

increased risk, which is considered to be five times greater than the

risk of the general population. Parents who have experienced a SIDS

death in their family may have concerns about their subsequent children.

These parents should discuss their concerns with their doctor, who may

arrange for an evaluation of the new baby.

Contact the National Sudden Infant Death Syndrome Foundation, 8240

Professional Place, 2 Metro Plaza, Suite 205, Landover, Maryland 20785

for information on crib deaths, [m.g.]

Cross-eye (strabismus). Many babies’ eyes “drift” during the first

few months of life. One eye or the other will turn in occasionally,

making the child look cross-eyed. Let your doctor decide if the

condition of your child’s eyes requires attention. If the baby’s eyes

are not straight most of the time by one month or all the time by 3

months, the doctor will probably suggest that the infant be referred for

a special eye examination.

If treatment for cross-eye is started early, chances of correcting the

cause of the disorder are excellent. The doctor may recommend

eyeglasses. The doctor may recommend that the child wear an eye patch

over the good eye to make the crossed eye work harder to develop good

vision. If these corrective measures fail to straighten the child’s

eyes, a surgical operation may be necessary.

If crossed eyes are not corrected, the child may lose the sight of the

crossed eye. [r.o.s.]

See also Eye health

Croup is a respiratory illness characterized by a hoarse, barking

cough and tightness in the child’s breathing. A child with croup makes a

harsh, wheezing noise when taking a breath (stridor). This may be the

result of an inflammation of the larynx (voice box) or the bronchi (air

passages) leading to the lungs.

Spasmodic croup, in which the child does not have a fever, is the most

common and mildest form of croup. It comes upon the child suddenly at

night and may be repeated for several nights. Humidify the child’s room

with a cool-mist humidifier or vaporizer. If neither is available,

create a steamroom in your bathroom by running a hot bath or shower.

Stay with your child to make sure the child does not get into the hot

water. Twenty minutes in a steamy bathroom should greatly ease the

child’s symptoms. Giving the child plenty of water and fruit juice will

also help. When you put your child back to bed, elevate the child’s head

and shoulders to make breathing easier.

Laryngobronchitis is a form of croup that is caused by a viral

infection. This type of croup is accompanied by fever and other coldlike

symptoms. The hoarse, barking cough and tight breathing can occur both

day and night. Steam or mist will not adequately treat this kind of

croup.

If your child has difficulty breathing, appears very ill, or does not

improve with cool mist, take the child to the doctor as soon as

possible. If you cannot reach the doctor, take the child to a hospital

emergency room. [m.g.]