Growth

By Deborah Rotenstein, M.D.

For every child, a primary task of childhood is to grow and develop

ultimately into a mature individual. Physical gi’owth begins with

conception. It is influenced by a variety of factors, many of which we

are only beginning to understand. The interaction between genetics and

environment results in a range of possibilities for children’s height,

and the rate at which children attain their genetic potential varies.

Growth rates

The most rapid growth and development take place during the 40 weeks

prior to birth. The fetus, which begins from a single cell, develops

into a group of cells, which become subspecialized. When a sufficient

number of cells have developed, organ systems emerge.

Birth usually occurs when the fetus is 40 weeks old, but some infants

are born earlier or later. So, even at birth, some infants are more

mature physically than others.

After the first 2 years, children begin to assume their individual

growth patterns, and after age 2 or 3, they assume the growth rate that

they will follow until just before puberty. For the first 6 months of

life, children grow at a rate of 7.2 to 8.8 inches (18 to 22

centimeters) per year. By 1 year, they grow at a rate of 4.4 inches (11

centimeters) per year. At 2 to 3 years they gi’ow 2.8 to 3.2 inches (7

to 8 centimeters) per year, and between 4 and 9 they grow 2 to 2.4

inches (5 to 6 centimeters) per year. Growth rates of less than 2 inches

or 5 centimeters per year after age 2 signal the need for medical

assessment. Because absolute heights at any given age may vary, it is

the pattern of growth that needs to be assessed.

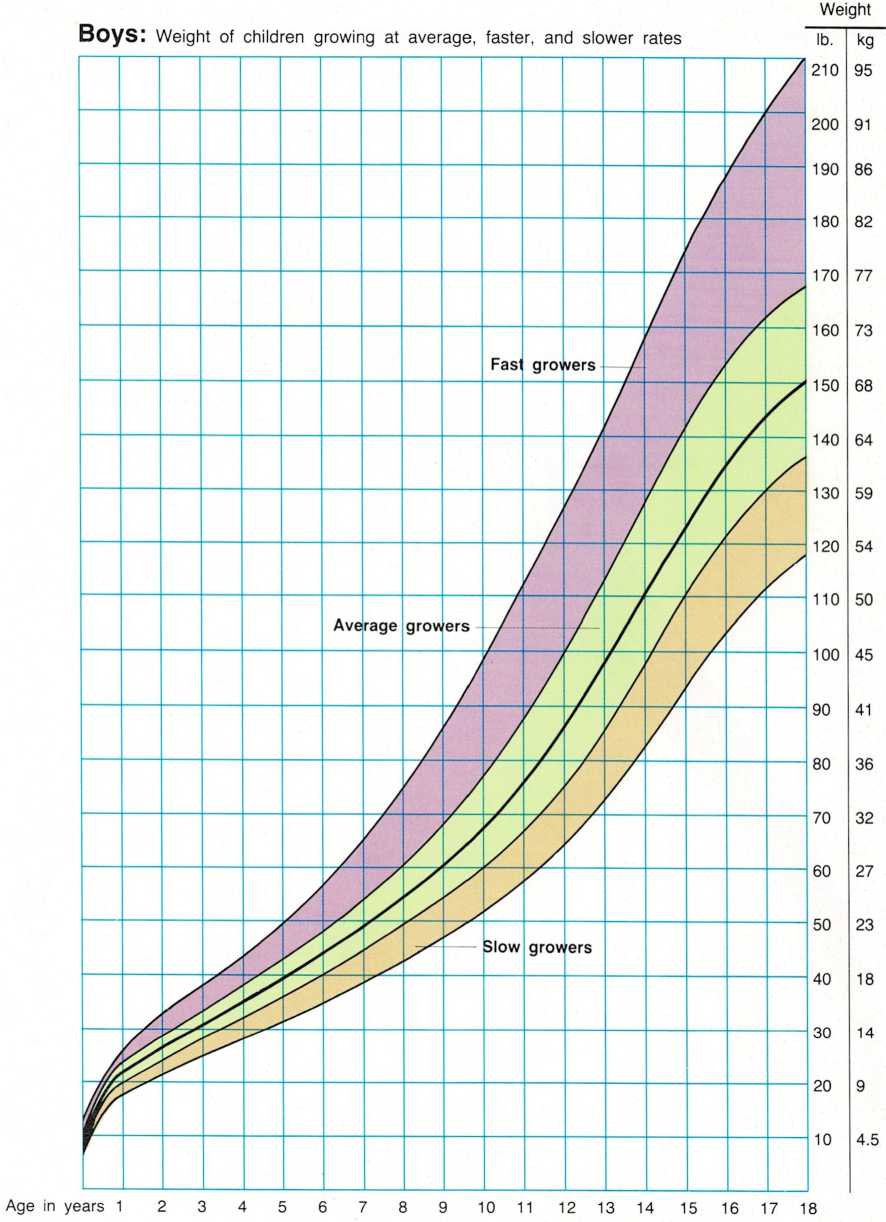

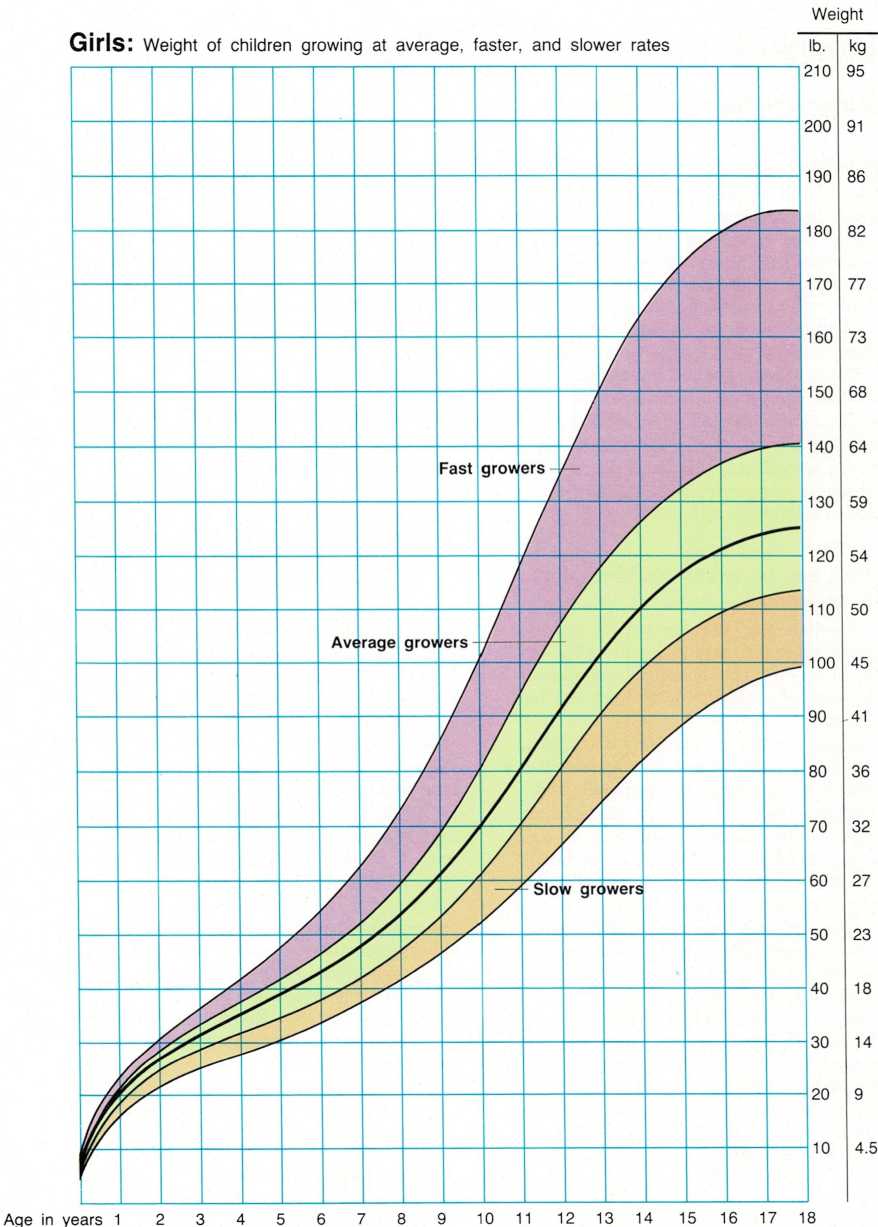

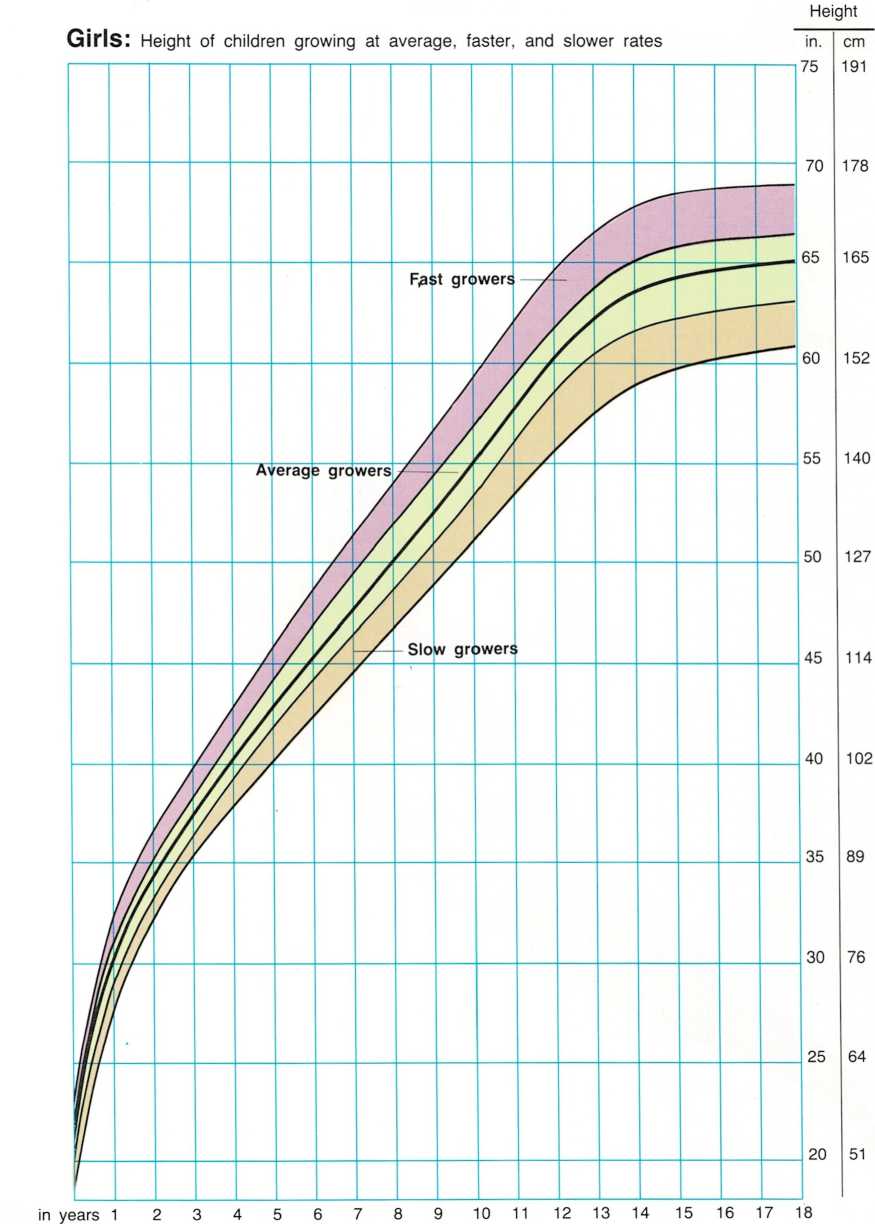

The growth in height and weight for boys and girls at different ages is

shown on the accompanying growth charts. Typical growth in height and

weight is shown by the heavy center line, and faster and slower rates by

the lines above and below it. The variation

in the curves of the lines shows that there are periods of rapid and

slow growth. After the fast growth of the first few years, the changes

become more gradual and then fairly steady. Thin layers of cartilage

called growth plates, found in all long bones, are active throughout

childhood in making the bones grow. There is a spurt of rapid growth

just before growth stops and the growth plates fuse.

The most valuable tool for assessing a child’s growth is a well-kept

growth chart. A child’s height and weight should be measured and

recorded on the growth chart at each visit to the physician. The most

widely used growth charts are made up for boys and girls of all ages and

are divided into ranges of height and weight by per cent. The age in

years is marked along the bottom of the chart, and height (inches and

centimeters) and weight (pounds and kilograms) are marked along the

sides.

Growth differences

Growth patterns of boys and girls differ. In the first 2 years, boys are

slightly taller than girls. After that, until puberty, the heights are

relatively similar. Girls’ skeletal ages—the degree to which their

bones have matured—are generally more advanced at any given age than

are those of boys. Children who are overweight often have a faster rate

of growth and reach puberty earlier than nonobese children.

A child’s rate of growth is not even; it may vary from year to year and

even from season to season, and is often fastest in the spring and

summer. For this reason, growth evaluations should always include

observation for six months to a year.

Short stature

About 3 million children in the United States are shorter than 97 per

cent of their peers. Most of these children are normal in

every way except that they are small. Not all short children have

abnormal growth. However, children who are not growing at an appropriate

rate should be evaluated by their pediatricians.

Some children may be short because they come from a short family, and

the genetic potential for height is small. Other children have a delay

in puberty or a delayed growth spurt, a condition called constitutional

growth delay. These children are shorter than their peers, but

ultimately will reach normal adult height.

World-wide, malnutrition or undernutrition is the most common cause of

short stature. Severe stress or a deprived environment can also cause

shortness. Many systemic illnesses, such as diseases of the heart,

lungs, pancreas (diabetes mellitus), kidneys, and digestive tract, can

cause poor growth, as can endocrine disorders, such as a lack of thyroid

hormone or lack of growth hormone. Growth hormone, which is one of the

hormones involved in the control of growth, can be completely or

partially deficient. Too much cortisol, a stress hormone, can also cause

shortness.

Children may be small for other reasons. Intrauterine growth

retardation— slow growth before birth—is one factor. It may be

caused by infection, or the mother’s use of alcohol, tobacco, or drugs

during pregnancy. Chromosomal abnormalities can cause shortness and

other genetic problems, such as Down’s syndrome or Turner’s syndrome.

Skeletal abnormalities or bone disease can affect the size and shape of

bones.

Occasionally a child is short for reasons that are totally unclear, and

no specific causes can be found. It is not unusual for children who are

under the age of 2 or 3 to cross percentiles in either direction on

their growth curves. However, after age 2 or 3, a fall away from the

growth curve signals that there may be a problem.

Therapy for shortness is directed at correcting the underlying medical

condition. Most children who are deficient in growth hormone can be

treated with gi’owth hormone only by a pediatric endocrinologist.

Children who are short because of delayed puberty, especially boys, can

also benefit from medical intervention. Psychological

support and/or counseling can often be very helpful to the treatment

process.

Tall stature

Just as there are many children who are small, there are about as many

who are taller than 95 per cent of their peers.

Most tall children have tall parents. Tall boys rarely complain about

their size. However, tall girls may feel ill at ease. Children who are

greater than the 95th percentile or who are growing—and continue to

grow— at an abnormally rapid rate should be checked by a physician.

Abnormal height is most often caused by an endocrine disease or a

genetic condition. There are several endocrine causes of abnormal height

and rapid growth. One is growth hormone excess, which may be caused by a

small tumor in the pituitary gland. A more common cause of unusually

fast growth is early puberty. Genetic conditions that cause abnormal

height are rare, and they often include abnormal body proportions.

Emotional factors of growth

Many short children adapt well to their size and may never have

psychological problems, but others do not. Our society places a great

value on height. Short children often face emotional stress from teasing

and may have difficulty coping. In fact, parents of short children

frequently have difficulty accepting a child’s height and treating the

child according to age level.

Teen-age years are often more difficult for the very short or very tall

child. Often problems of short stature are made more difficult by the

lack of sexual development. For short teen-agers, one problem is being

treated as if they are younger than their actual age, and some of them

react by behaving imma- turely. Tall teen-agers may feel conspicuous and

become very self-conscious.

Of course, a child who has a medical problem should be treated. But

children also need to feel loved whether they are short or tall. For

parents and other adults, one of the most important steps in making life

easier, for a short or tall child, is to accept the child’s size.

Age