Behavioral disorders in children

By Jerome L. Schulman, M.D.

At times, all children behave in ways that puzzle or worry their

parents. Many children may even show what seem to be symptoms of a

behavioral disorder. Symptoms such as extreme aggressiveness, fears, and

compulsions indicate a behavioral disorder only when they are severe or

occur frequently. Be careful not to let your concern about your child’s

behavior exaggerate the significance of a symptom. Fortunately, most

children are mentally healthy.

Behavioral disorders and developmental challenge are different from one

another, but sometimes it is hard to tell them apart. Emotional problems

may make learning so difficult that even a normally bright child may

appear developmentally delayed. (See [The developmentally challenged

child] in For Special Consideration.)

The importance of physical health

Before concluding that a behavior problem is the result of emotional

disturbance, you should be certain that your child does not have some

physical illness. Many symptoms of behavioral disorder can be created or

made worse by a physical illness. Regular medical checkups are

important. They become even more important if your child is having an

emotional problem.

Where emotional problems can occur

A child may be thought of as living in four worlds and being expected to

behave in

certain ways in each of these worlds. If the child’s behavior is

frequently very different from what is thought of as normal, there may

be a behavioral disorder.

Family and home—the first world

A child’s first world is the family and the home. One’s attitude toward

oneself, toward other people, and toward life in general begins here. In

a normal situation, there is a bond of affection between the parents,

and between the child and each parent. They enjoy each other’s company,

but each has other interests. Gradually, the child moves from almost

total dependence in infancy to almost total independence toward the end

of adolescence. Throughout these years, the child is expected to pay a

reasonable amount of attention to family rules and to perform tasks that

are reasonable in terms of age and ability.

A child may have a behavioral disorder if there is not a good

relationship with parents, if independence proceeds too slowly or too

rapidly, or if family rules and tasks are ignored. Attitudes toward

other children in the family are hard to classify because quarreling and

jealousy are a normal part of the brother-sister relationship. They

seldom indicate a behavioral disorder.

School—the second world

A child lives in this second world about 1,000 hours a year during

childhood. A child’s tasks in school are, within reasonable limits, to

perform well and to conform socially, to be interested in studies, to

see learning as an opportunity for a full and

productive life, and to become interested and involved in

extracurricular activity.

All parents have ambitions for their children. A problem may occur if

the child’s ability does not match the parents’ expectations. The

child’s attitude toward school may become bad, or achievement may fall

below ability. Also, if behavior at school makes frequent discipline

necessary, it may indicate a behavioral disorder for which help is

needed.

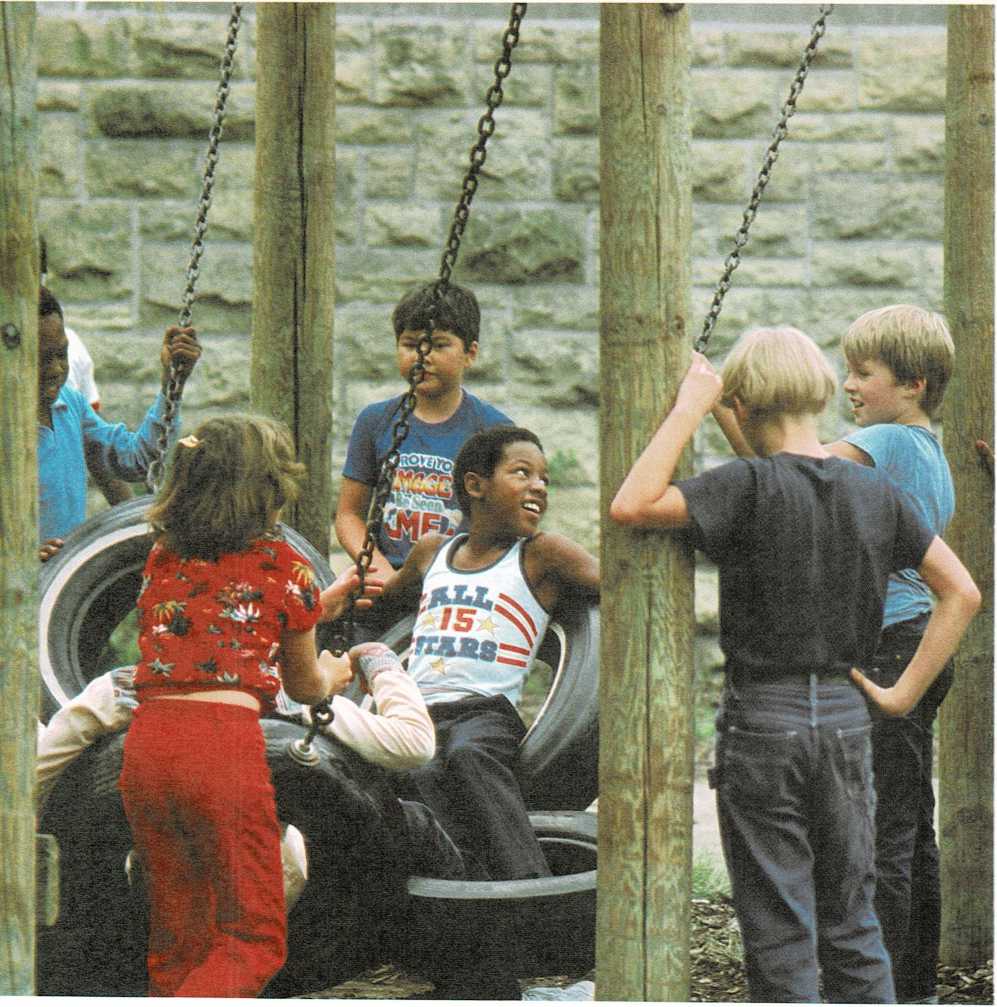

Friendships—the third world

As children move from infancy into childhood, they encounter a third

world—the world of friendships. This world becomes increasingly

important as children grow older. Childhood associations are extremely

important. Children begin to learn social customs and patterns of

behavior by imitating adults and by influencing and being influenced by

other children. Much of the ability to be good at adult relationships

grows gradually out of a good childhood beginning. Normally, the child

should want to be with friends and should feel wanted by them. They

should enjoy being together.

Parents should be concerned about the child who is always alone, the

child who tries to buy friendship with bribes, the child who either acts

the fool to get other children to laugh at him or her or who is

aggi’essive toward other children, and the child who always prefers to

play with much younger or much older children. And certainly parents

should be concerned about the older child whose friendships lead to

antisocial behavior such as vandalism or stealing.

The inner world—the fourth world

The child’s inner world is in some ways the most important and the most

difficult to understand. It is the world of thoughts, fears, hopes,

attitudes, and ambitions. Children see themselves in many ways. They may

think of themselves as smart or stupid, lovable or unlovable, ugly or

good-looking, good or bad. Together, these self-evaluations make up what

is known as the self-image. When a child has a strong and continuous

feeling of not measuring up to other children, it is reasonable to

assume that there is an emotional problem.

Everyone has to face problems of one kind or another throughout life. In

spite of this, the well-adjusted person continues to find life a source

of satisfaction. Such a person is usually optimistic about the future.

If this feeling of optimism never occurs, then there is an emotional

problem.

Specific symptoms

The most serious symptoms of behavioral disorder may be referred to as

thinking disorders. They may occur singly or in combination. A child who

is unable to respond to people or surroundings or is completely without

a sense of time has a thinking disorder. The child may hear voices or

see things that do not exist. This should not be confused with the

behavior of the normal child, who may sometimes play with and talk to an

invisible friend.

Obsessions are thoughts that occur repeatedly until they interfere with

normal thought processes. At times a normal child may have an experience

similar to an obsession, such as a tune that keeps running through the

mind. This is short-lived and does not interfere much with normal

thought processes.

Compulsions are urges to repeat certain acts over and over even though

there is no reason to do so, such as the uncontrollable urge to

repeatedly wash the hands. This is not the same as a child’s urge to

avoid stepping on cracks in a sidewalk, which is more a game than a

compulsion.

A phobia is a fear so terrifying that it prevents the child from

carrying on normal activities. It is one symptom of a behavioral

disorder that gives parents much concern. This is not to be confused

with the normal child’s dislike of school at certain times, or with a

young child’s fear on first entering school.

Anxiety is a nameless dread not related to anything specific. Anxiety is

harder to understand than a phobia because the cause of the child’s fear

is hard to pinpoint.

Extreme aggressiveness, such as a compulsion to hurt other children or

to be cruel to animals, must also be considered a symptom of a serious

behavioral disorder if it is frequent.

Some symptoms of behavioral disorders interfere with the normal body

functions. Among these are tics, hysteria, enuresis (regular

bed-wetting), and encopresis (the constant inability of the child to

control bowel movements).

Tics, or habit spasms, are sudden repeated movements of muscle groups.

Generally these occur in the muscles of the face, but they may involve

any muscle group. The child has no control over a tic.

Hysteria is best described as the loss of a physical or sense function

because of emotion. Hysteria may cause blindness or the loss of the

sense of touch. It may also cause paralysis of arms or legs.

Enuresis and encopresis may be considered symptoms of a behavioral

disorder if they occur in a child who has previously been bowel and

bladder trained.

What to do about behavioral disorders

If your child frequently shows symptoms of a behavior disorder, do not

ignore the symptoms and hope they will disappear in time. Your child is

too important for you to rely on chance.

Parents should discuss the problem together. It is extremely important

that the discussion take place during a time of calm and good feeling

rather than when parents are upset and angry because the child has

behaved badly.

During the discussion, parents must decide how the family as a group,

and each member, behaves differently from the average. Do not hesitate

to admit that your own behavior may be different. In a variety of ways,

everyone is likely to be on one side or the other of the average.

Also, you must be able to admit that while the ways you do things may

work well with some children, and may even be necessary, they have not

been successful with the disturbed child. This admission calls for a

willingness to accept the fact that your behavior is related to your

child’s difficulty, and that a change in your approach to the child may

be a solution to the problem.

Parents may have problems

The perfectionist parent believes there is a place for everything and

that everything must be in its place at all times. As a result, demands

on the child are often unreasonable. The child’s room is never kept neat

enough to please the perfectionist parent. If the child gets a “B” on an

otherwise straight “A” report card, the child is criticized and made to

feel inadequate. The child is constantly compared to others, but no

matter how hard the child tries, the perfectionist parent is never quite

pleased. Emotional problems of the child can often be related to this

abnormal demand for perfection. The perfectionist parent should try to

be less rigid about rules and to look for behavior that can be praised.

The inconsistent parent creates an uncertain environment by changing

rules so often that the child cannot know what is expected. Most parents

are inconsistent at times, but when they constantly change rules

relating to the child’s behavior, it is damaging to the child and should

be corrected.

The overprotective parent shields the child excessively, either

because the parent cannot bear the thought that the child is growing up,

or because of undue concern for dangers in the world outside the home.

This attitude may inhibit the development of independent skills. The

parent who recognizes that overprotection is a problem can find a

reasonable guideline for correcting it by studying the behavior of

parents with well-adjusted children.

The indulgent parent buys the child’s affection by never setting any

limits. This may also be the source of the child’s behavioral disorder.

Children are much more comfortable when they have rules to follow. Rules

prepare a child to face the many situations where individual desires

must be put aside in favor of group needs.

Quarreli\’ng parents may also contribute to a child’s problems, if the

quarreling is constant. The obvious solution is to avoid quarreling in

the child’s presence and to compromise their differences.

The uninvolved parent has little to do with the child. Such a parent

will be unable

to convince the child of his or her love, interest, and concern.

Children need models after which they can pattern their own behavior. To

be effective models, parents must be available and interested in the

child.

The punishing parent tends to deal with problems by thinking up new

and unusual punishments. Although punishment may be essential on some

occasions, it should not be excessive, and there should be sufficient

praise to counterbalance it. If a child shows symptoms of a behavioral

disorder, and has been punished a great deal, it is reasonable to assume

that more punishment will only tend to aggravate the condition.

Changing tactics

When parents recognize that previous methods of handling their child

have been unsuccessful, and even harmful, they should plan a new

program. If the child is old enough to reason with, the process will be

made easier by a frank discussion when all are feeling friendly. The

parents should tell the child how concerned they are and how much they

want to help. They should indicate to the child how they plan to change

their behavior, and they should agree to meet on a regular basis to

discuss progress. The child should be allowed to speak freely during the

discussions, and nothing the child says should be held against him or

her.

If the child’s behavior has become a problem at school, it is important

that parents discuss the problem with the child’s teacher and other

staff, such as the principal, the school psychologist, a social worker,

or the school nurse. These people are interested in the child and can

offer advice and guidance. This may be extremely valuable in helping

parents understand why their child is behaving badly.

When to seek professional help

Usually, it is difficult for parents to admit, even to themselves, that

their child may need psychological support. And it is reasonable for

parents to assume that they can work on some of their child’s problems

with

out outside help. If there is any improvement, they should continue. But

if in a reasonable time, there is no improvement, it is time to seek

professional help.

If the child’s problem is in the category discussed under “Specific

symptoms,” parents should consult their pediatrician or the family

doctor. If necessary, the parents will be referred to a psychiatrist, a

clinical psychologist, or to the local mental health clinic. Often it is

easier for an outsider, especially one with specialized training, to

approach the problem with greater objectivity or from a different point

of view.

When parents seek help for their child, they must be prepared to accept

the fact that they may be partly responsible for their child’s emotional

problem. Parents should be willing to learn how they have contributed to

the problem and to work with the doctor to produce good results.

Children with behavioral disorders tend to respond favorably to

treatment, especially when all members of the family are trying to help.

The treatment of an emotionally disturbed child often requires a great

deal of time and patience on the part of parents and child guidance

specialists.

For one thing, a disturbed child is, as a rule, completely unaware that

anything is the matter. For another, disturbed children seldom want to

change their ways. The professional working with the child may need time

to bring the child to the point where the child wants to do something

about the behavioral disorder.

Parents should not be discouraged if psychiatric treatment or treatment

in a child guidance clinic fails to produce immediate results. Diagnosis

and treatment take time, and the results may be slow in coming. A severe

behavioral disorder usually takes a long time to develop. It follows

that as long a time may be required to correct it.

Fortunately, many of the emotional illnesses of children can now be

treated successfully. Ongoing research in the important field of mental

health should offer even more help in the future.

Mark S. Puczynski, M.D. Consulting Editor