Common concerns

The preschool period can be a happy time in family life, free from

overwhelming problems. One reason for this is that preschool children

can do so much more for themselves. They can be independent in feeding

themselves, in dressing, and in using the toilet. They are no longer the

physical drain on their parents that they were as infants. Another great

help is their delight in the world and in the people around them. Their

eagerness, openness, and good feelings about being alive can be quite

contagious. No age, however, is completely angelic. There are always

some rough spots.

Dawdling

The conflict between a young child’s time schedule and that of parents

is often a trouble area. Most adults have watches on their ■wrists. They

are going somewhere and know exactly how many minutes they need to get

there. Young children loaf along and dream along, undriven and

unpressured. Adults call this pace “dawdling.” Children, of course, have

no special name for what they do. This slower pace is the way they act.

It can take a child what seems like ages to finish eating, to get

dressed, or to “come along.” The child tends to stop and fascinatedly

watch the world go by. This special pace is a part of being a 3-year-old

or a 4-year-old. It is a part of the newness of being able to do things

for one’s self—a part of the wonder at the world.

The best approach for coping with dawdling is to make some minor

adjustments.

For example, with eating and dressing, allow as much time as possible so

that your child has leeway for dreaming. But if something pressing lies

ahead, pitch in with a helping hand to speed up the eating or dressing

process. Do not nag or pester. Angry words seldom produce a speed-up.

There will be times when reality demands that the meal be ended—the

available time has simply run out. There is no great harm in a child’s

experiencing this. The harm comes only when—as the food is taken

away— adult anger, nagging, and complaining come to take its place.

It may help you to keep your balance if you remember that this slow pace

does not go on forever. The time is not far distant when you may worry

more because your child bolts food and jumps into whatever clothes are

left around.

Fears

Some problems arise, too, because it is so easy to forget that the

3-year-olds in particular, but also the 4-year-olds, are still little,

dependent children. They have grown so much. They can do so much more

for themselves. But they have many moments when they feel like the

“little babies” that they, in part, still are. When parents forget this,

they often are harsher than they should be. This is especially true when

these children get frightened. And a wide, unpredictable range of events

and sounds and sights can scare them. Preschoolers are still new to this

world. And every day, their gi’eater

mobility opens up more and more of the world. The loud, the unexpected,

the new, the big, the fast-moving, the dark—it is hard to know what

will take their breath away next, but a great many events can.

The quick, easy response is the pep talk: “You’re not afraid of a little

thing like that, are you?” Parents are not afraid, but parents are

old-timers. The preschooler’s only reply, which is often screamed with

the whole body, is to say in effect, “I certainly am afraid . . . that’s

what this fuss is all about.”

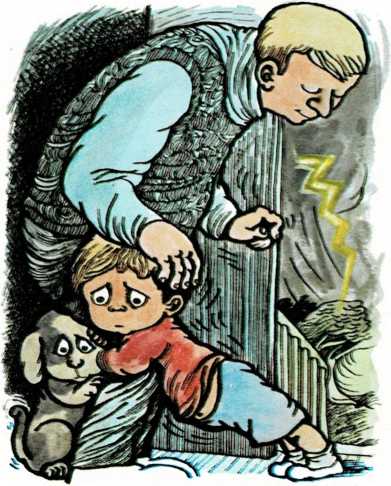

Worse than the pep talk is unsympathetic scoffing and shaming: “Don’t be

a little baby . . . Don’t be a scaredy cat . . . You’re supposed to be a

big (boy or girl).” When children are afraid of dogs, of thunder and

lightning, or of the dark, it hardly helps to have the added fear of

losing their parents’ love and respect.

A much more effective way to deal with fright is to accept the fact that

your child is frightened. Give support and comfort so that the child

feels strong enough to face the frightening event. Sometimes just moving

over to stand by the preschooler’s side is all the support that is

needed. Sometimes this,

Accept the fact that your child has fears.

Then give the support and comfort needed.

plus a comforting word or two, does the trick. Youngsters who are deeply

upset have to be held and patted and comforted. The goal is to give

enough support so that they feel better, without doing so much that they

feel pushed back into babyhood.

Then, when your child has calmed down a bit, try to teach the youngster

how to cope with the experience the next time it happens. The more

competence the child has, the fewer fears there will be. Explain the

cause of thunder and lightning, or why it gets dark. Teach the

preschooler where to pat a dog, how to hold the hamster, so that the

child can manage the situation the next time it arises.

The most upsetting fear of all, of course, occurs when children think

their parents do not love them. Any one of a wide variety of happenings

can start this unhappy train of thought. Being left alone in a strange

new setting like a hospital, a doctor’s office, Sunday school, or

nursery school can start it. The hazard is separation. Young children

easily translate “Separation . . . they are leaving me” into “Separation

. . . they don’t love me.” Harshness, coldness, and busyness can have

the same effect. The child feels alone and unprotected.

Sometimes the events parents think ought to make a child feel big have

the opposite effect. A new baby in the family and starting school are

two examples. The wise approach is the same as with all fears. Give

support and be understanding until the child is able to cope with the

problem.

Toilet-talk

Some troubles come along in these years because preschoolers are still

young children. But other difficulties pop up because these are such

“big-feeling” children. Much of the time these youngsters want to feel

big, and much of the time parents are glad about this feeling. But there

are moments when almost every parent wants to say, “Slow down … Not

THAT big!”

Because of their increased control of language, preschoolers do not have

to use gross, physical displays to prove their bigness—as they did

when they were only 2. Tantrums are rarities, almost nonexistent.

Reasoning is the best approach to discipline. But it is a slow

method requiring patience.

But the more refined ways can be as irritating and as troubling as the

grosser ways.

Three-year-olds, and especially 4-year- olds, are apt to use toilet-talk

because they sense it is “shocking language” and a means of seeming big,

tough, and clearly independent. Words like “do-do” and “grunt-grunt” and

“wee-wee” become, for a while, standard adjectives to describe anything.

Some families simply live with these sounds. The “shocking” noises run

down after a while as children find other, more “improved” and “mature”

ways of making the same point. Some families let the noises go for a

period and then, when they think the children have made their point, say

“That’s enough of

that.” Or they give them some funnysounding substitute word.

Discipline

Developing good discipline in children is one of the most important jobs

of parenthood. But this vital task takes time, patience, and

understanding.

Many parents believe that discipline and punishment are the same thing.

But punishment is only one of several ways to teach discipline. It is

not the only way, nor is it the best. It is, in fact, the most difficult

to use wisely, and often produces the very opposite of the result

parents want.

Many parents also believe that children resent discipline. These parents

not only hesitate to punish their children, but seldom use any of the

better methods to build discipline. They want to be good to their

children and end up by being too lenient. Undisciplined children are

almost always unhappy children. They never know what the limits are, and

this is unsettling. They need someone to teach them what is right and

what is wrong, and why.

Wise parents do not shrink from disciplining their children. But instead

of using one method all the time, they seek, instead, to puzzle out why

their children misbehave, and then to take whatever action best fits the

situation. For example, young children often misbehave because they

simply do not know any better. When this is the problem, one

appropriate method of discipline is to patiently explain what the rules

are and why rules are important. You try to teach so that your child

will understand.

Teaching is effective only if parents believe in what they are saying.

Their way of talking must convey that the lesson is important. And the

process must never be one of “talking to the wind”—to a child who pays

no attention, or listens with only half an ear. When you say, “Stop,”

and tell the child why, the action must stop—at least for that moment.

For example, if your child is beating on a window with a stick, say very

firmly:

“Stop that. Windows are made of glass, and glass breaks easily. So don’t

hit the window with your stick. The window may break.”

Take the stick away, and move the child away from the window.

Reasoning is a slow method. You cannot expect a child to learn because

you talk over an incident just once. But in the long run, reasoning is a

good method because it helps children learn values that they can act on

when they are on their own. It is also a method that respects the

child’s growing independence.

Besides explaining and giving reasons, you should praise your children

when they act well. Praise, especially when it directly follows good

behavior, is a booster to learning. For example, if your child comes to

the ta

ble with clean hands, or acts in a way you expect, offer immediate

praise. You might say, “That’s good!” or “I like to see that!” or

whatever honest words of praise fit the situation. Your welcome approval

reinforces the child’s good behavior, making it more apt to be repeated.

“Not knowing any better” is only one reason for misbehavior, just as

reasoning is only one method for teaching discipline. At times, children

do the wrong thing because of the setting they are in. When this seems

to be the case, the way to discipline is not by talking, but by action.

Change the setting to make it easier for the child to be good. This

approach is especially useful with children too young to really

understand words, but it also works with older children. For example,

things that a toddler should not touch should be put out of reach. Older

children who have to sit for a long time on a car ride or while waiting

in a doctor’s or dentist’s office will behave much better if you give

them a book to read or color, or a game to play.

Another reason for misbehavior lies in children’s feelings. Children

have to feel right to act right. Some boys and girls are driven to bad

behavior because they desperately need more love, or more attention, or

a feeling of importance. They do things they know they should not do. A

jealous child, for example, may hurt a baby sister or brother. Of course

the baby must be protected, and the behavior must of course be stopped.

The temptation is to punish children driven by upset feelings, but the

surest way to help them is to give them the love, or attention, or

importance their behavior shows they need.

Parents have to be thoughtful in choosing an approach to discipline, one

that fits the child and the situation. This sensitive process of

deciding what action to take itself contributes to discipline. It is an

expression of love, and the foundation of all good behavior is a child’s

sense of being loved. Children unconsciously identify with parents who

show their love. Slowly but steadily, they will take on the attitudes

and values of their parents. What is learned through this process of

identification does not show up immediately, but the lessons are

instilled in the child. Good behavior will evolve in time.