Feeding the baby

Many mothers are now choosing to breastfeed their new babies. This

pattern has been encouraged by physicians and nurses because of the

recognized benefits of breastfeeding to the infant—and the mother. The

newborn infant receives valuable protection against infection in the

first few days of life from colostrum—the clear fluid which precedes

the production of milk.

To get a big, healthy burp, gently pat or rub the baby’s back.

In many parts of the world, breast milk is the safest pattern of

feeding, since it is not dependent on the availability of pure water

and/or refrigeration.

Many people advocate breast-feeding as the optimum way to foster the

mother-child relationship. It should be pointed out, however, that

bottle-fed babies are held in essentially the same position for feeding

and that most infants and mothers “bond” independent of the method of

feeding or the feeding pattern.

Fathers of breast-fed babies should be encouraged to be involved in the

early care of the infant in many ways. Some mothers will pump their

breasts to allow the infant to feed from a bottle once a day (or night).

This allows the father to participate actively in feeding.

If you choose breast-feeding, your doctor will probably recommend that

the baby be given vitamins with fluoride daily. (Most infant formulas

are supplemented with vitamins.)

Whether you breast-feed or bottle-feed, doctors usually recommend

following a modified demand feeding schedule during the baby’s first few

weeks. The baby usually takes two to three ounces (60 to 90 milliliters)

of milk or formula at each feeding. Then, after sleeping for 2 to 3

hours, the baby awakens for the next feeding. As the baby grows, the

stomach capacity increases. At 8 to 12 weeks, the baby will take four to

six ounces (120 to 180 milliliters) at each feeding and require only

five or six feedings every 24 hours.

Babies sometimes spit up their feeding, usually just a few minutes after

they have finished. This may be just a dribble of several drops of milk.

If spitting up happens more than one-half hour after the feeding, it

will probably be a cheesy material that smells sour because the stomach

juices have already started to curdle the milk for digestion. Do not be

alarmed. These babies usually weigh enough for their age. The spitting

up probably is caused by an overflow from a full stomach.

In some cases, the baby spits up early during a feeding. When this

happens, the baby’s stomach may be filled with air from crying or from

improper feeding techniques.

If this seems to be the ease, burp the baby before and several times

during feeding. After the baby has been fed, hold the baby upright on

your lap or over your shoulder (with a diaper or cloth to protect your

clothing) and pat or rub the baby’s back until you hear a burp. You can

also prop the baby up against a cushion for 15 to 20 minutes after the

feeding. Never feed the baby by propping a bottle in the crib. By doing

this you and the baby miss the mutual pleasure of feeding, and the baby

might choke on the milk.

Breast milk and infant formulas provide an adequate source of iron and

are recommended for the first year. Cow’s milk is a poor source of iron

for infants.

Weaning

Wean your baby\’gradually from the breast or the bottle, allowing plenty

of time for the baby to get used to a new way of eating. The baby will

decide when the time is right. All you have to do is follow the baby’s

lead. At about 5 or 6 months, provide an empty cup as a plaything. Then,

one day, offer a few sips of milk from the cup. Gradually, over the next

several weeks, the baby may learn to enjoy drinking from the cup. At

each feeding, give the baby as much milk as he or she will take from a

cup. Then allow the baby to nurse or offer a bottle. After a while, omit

the daily breast- or bottlefeeding that the baby is least interested in.

This is usually the breakfast or lunch feeding. Offer only a cup of milk

at this time. After a week, omit another breast- or bottle-feeding, if

the baby is willing. Then, in another week, omit the last of the

feedings by breast or bottle. Some mothers, however, wish to continue to

breast-feed through the baby’s first year. Infants of these mothers may

need additional sources of iron in the second 6 months of the first

year. (See Solid foods.)

Babies’ willingness to be weaned may vary. Teething babies or ill babies

may revert to the bottle. Babies may be entirely weaned at one year old,

or they may cling to an evening bottle for a longer time. It may be

comforting to note that it is rare to see a child entering school with a

bottle in a lunch box.

This table can be used as a guideline for introducing your baby to solid

foods.

Age Food

4 Cereals: Rice, oatmeal, barley,

months wheat, mixed cereals

5-6 Fruits: Applesauce, pears,

months bananas

6-7 Vegetables: Carrots, squash,

months peas, sweet potatoes,

spinach, beans

7-8 Meats: Lamb, chicken,

months beef, liver, veal

After 9 Egg yolks, finger foods, months table foods

Solid foods

Many mothers regard the introduction of solid foods as the surest sign

that their babies are growing up. Some feel that solid foods make babies

sleep better and longer at night. But feeding of solids may be started

too early. In some cases, when a spoon touches the front part of the

baby’s tongue, the tongue rapidly attempts to push the spoon out. Too

early attempts are also generally frustrating and messy, since most of

what does get into the child dribbles right back out again. The

frustration involved in overcoming the baby’s efforts to fend off food

can set up a poor eating pattern. Mealtimes should be pleasant

experiences, not battles between opposing forces.

Most pediatricians recommend waiting until a baby is 4 months old before

introducing foods by spoon. At this time, start strained foods in small

amounts, increasing the amounts as the baby’s capacity and interest

increase. The first foods introduced should be cooked, strained cereals

with iron added to them. A teaspoon of rice cereal mixed with enough of

the baby’s formula to give it a smooth consistency is an excellent first

food. Although the rice may be tasteless to you, it offers a new and

important experience for your baby. The baby’s tongue feels a new

consistency. Cereal should not

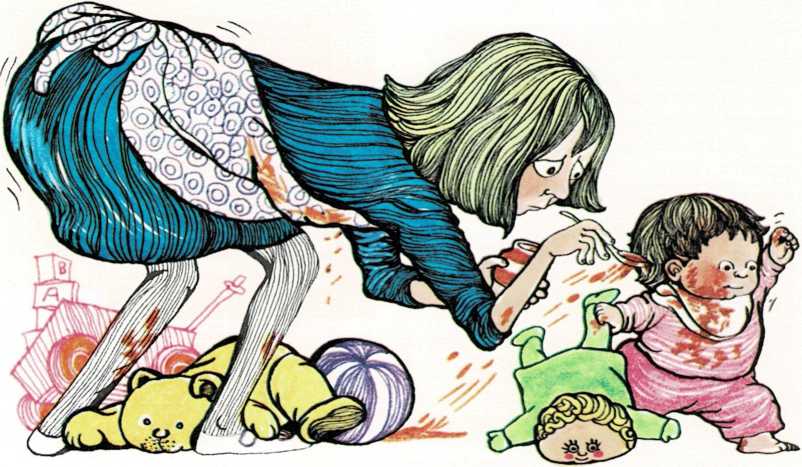

“They’re off and running!” is the starting cry of many a meal when

baby learns to walk.

be added to the milk in the baby’s bottle because this deprives the baby

of a pleasurable learning experience. Rice cereal is good to start with

since it is unlikely to cause allergic or other reactions (such as

diarrhea). After a few days, oatmeal, barley, wheat, and last of all,

mixed cereals can be introduced one at a time.

After cereals, introduce other strained foods, one food at a time. Then,

if any reaction occurs—such as a rash or diarrhea— you can easily

identify the offending food.

Some parents prefer to prepare their own strained foods for their baby.

This has the advantage of ensuring that there are no chemical additives

in the foods. Be sure not to flavor the foods to suit your taste.

Especially, do not add unnecessary salt or sugar to the prepared foods.

A variety of devices are available to grind and puree foods. Some of

these are very expensive, but others, such as a blender or foley mill,

can be purchased at more modest prices and are perfectly adequate.

Introduce junior foods (still mostly strained, but with some chunks of

food) when the child has one or two primary teeth (6 months old or

later). Some babies prefer to skip junior foods and go directly to

mashed potatoes, cottage cheese, eggs, ham

burger, and other table foods. Most babies at this age also enjoy hard

cookies and toast. By the time they are a year old, most children enjoy

sucking and gnawing at a chicken leg or lamb chop.

Mealtimes

At about one year, your child may appear to eat less, even though he or

she is becoming more active. A mother who complains that her child is

not eating may be surprised to discover that the child is gaining

weight. At this age, the tremendous growth rate which has taken place

during the baby’s first year tapers off. The child moves around more and

spends relatively less time eating. Often a considerable amount of

ingenuity is required to prevent mealtime from deteriorating into a

chase or a battleground.

The 1-year-old should be eating about three times a day and learning the

meaning of mealtime. Feed the child at the table at about the same time

as the rest of the family. To avoid too much disruption, you may feed

meat and vegetables first, and then let the child eat dessert while the

family eats dinner. Offer small portions that the child can finish. If

the portions are not enough, offer second helpings. This technique

avoids the situation in which the 1-year-old is faced

with a seemingly overwhelming amount and choice of foods, a situation

that will force a small child to either surrender and be stuffed full,

or to rebel and not eat at all.

Encourage self-feeding by cutting the food into bite-sized portions that

are easy to handle. Do not expect a 1-year-old to be adept with a spoon

and fork. Expect a fairly messy high chair, clothing, and baby after

each meal. However, some limits must be set. Do not let the child throw

food around. This can be especially embarrassing when visiting friends

or relatives. On such visits, you may want to bring along a plastic

garbage can liner to place under the high chair or feeding table. This

allows for quick cleanups and saves carpet cleaning and bad feelings

among friends. If the child does not eat enough at mealtimes, do not

allow between- meal snacking. This will lead to more difficulty at the

next meal.

Sometimes a 1-year-old begins to drink more and more milk at the expense

of meats, vegetables, and other foods. This may follow an illness, or it

may be because the child is teething. But often it is a result of

mealtime conflicts. The bottle seems a simple solution to getting what

an adult feels are adequate calories into the child. But, milk lacks

iron. If this “simple solution” continues beyond a few weeks, the child

may suffer serious iron deficiency leading to anemia. As a rule of

thumb, it is best to limit milk intake at one year to 24 to 32 ounces

(70 to 95 milliliters) at most per day.