Milo in Digitopolis

from The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster

“I hope we reach Digitopolis soon, said

Milo. “I wonder how far it is.”

Up ahead, the road divided into three and, as if in reply to Milo’s

question, an enormous road sign, pointing in all three directions,

stated clearly:

DIGITOPOLIS

5 Miles

1,600 Rods

8,800 Yards

26,400 Feet

316,800 Inches

633,600 Half Inches AND THEN SOME

“Let’s travel by miles,” advised the Humbug; “it’s shorter.”

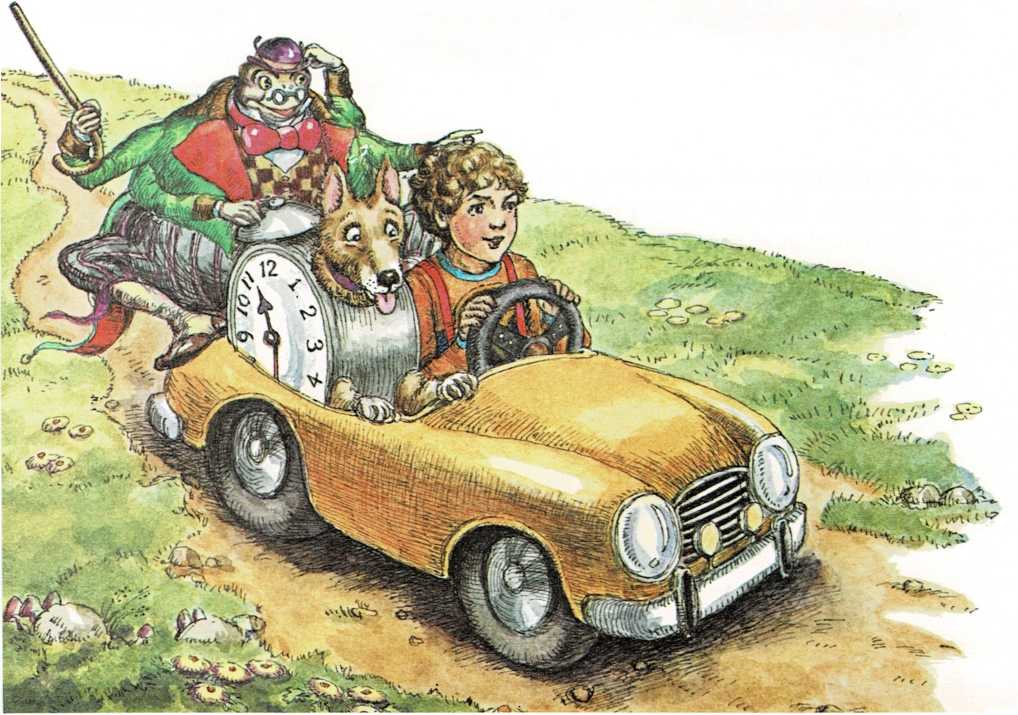

The book The Phantom Tollbooth is about a boy named Milo and his

fantastic adventures in the “Lands Beyond.” This is a strange place,

where words, names, and expressions mean exactly what they say. For

example, Milo meets a dog named Tock, who is a watchdog—part watch and

part dog I As we pick up the story, Milo, Tock, and a large insect

called the Humbug, are driving along a road to the Kingdom of

Digitopolis, which is ruled by a person known as the Mathemagician.

}IJh\^

“Let’s travel by half inches,” suggested Milo; “it’s quicker.”

“But which road should we take?” asked Tock. “It must make a

difference.”

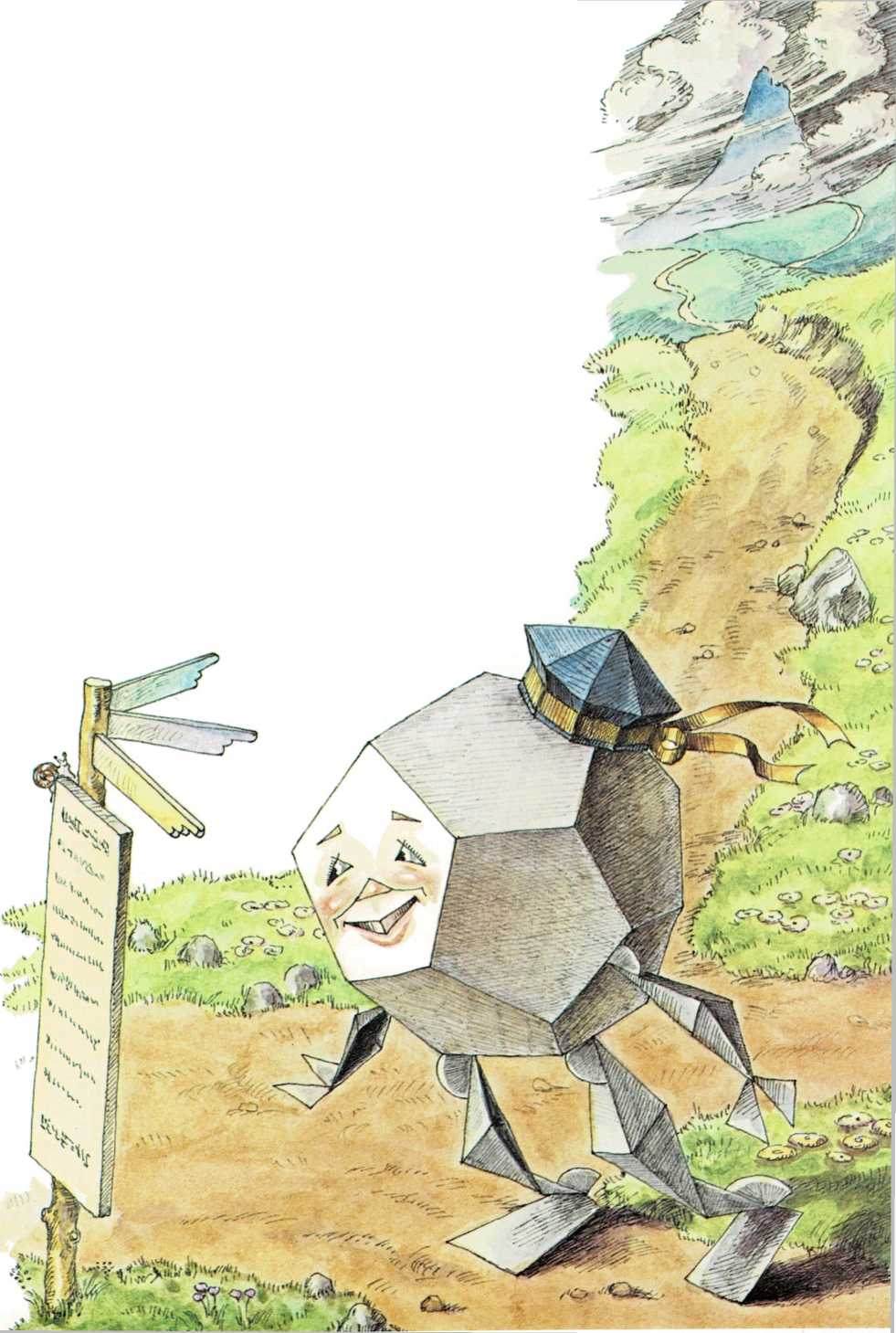

As they argued, a most peculiar little figure stepped nimbly from behind

the sign and approached them, talking all the while, “Yes, indeed;

indeed it does; certainly; my, yes; it does make a difference;

undoubtedly.”

He was constructed (for that’s really the only way to describe him) of a

large assortment of lines and angles connected together into one solid

many-sided shape—somewhat like a cube that’s had all its corners cut

off and then had all its corners cut off again.

When he reached the car, the figure doffed his cap and recited in a

loud, clear voice:

“My angles are many.

My sides are not few.

I’m the Dodecahedron.

Who are you?”

“What’s a Dodecahedron?” inquired Milo, who was barely able to pronounce

the strange word.

“See for yourself,” he said, turning around slowly.

“A Dodecahedron is a mathematical shape with twelve faces.” Just as he

said it, eleven other faces appeared, one on each surface, and each one

wore a different expression. “I usually use one at a time,” he confided,

as all but the smiling one disappeared again. “It saves wear and tear.”

“Perhaps you can help us decide which road to take,” said Milo.

“By all means,” he replied happily. “There’s nothing to it. If a small

car carrying three people at thirty miles an hour for ten minutes along

a road five miles long at 11:35 in the morning starts at the same time

as three people who have been traveling in a little automobile at twenty

miles an hour for fifteen minutes on another road exactly twice as long

as one half the distance of the other, while a dog, a bug, and a boy

travel an equal distance in the same time or the same distance in an

equal time along a third road in mid-October, then which one arrives

first and which is the best way to go?”

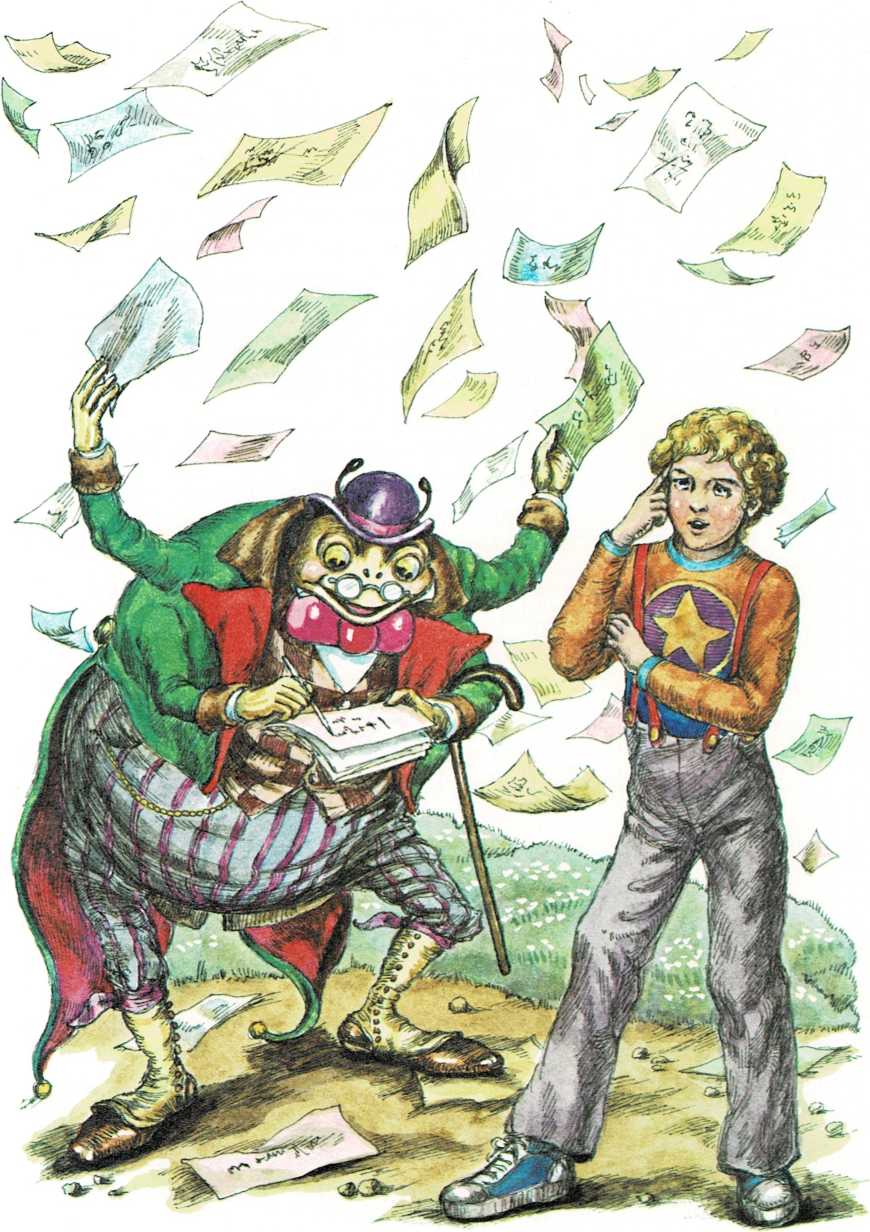

“Seventeen!” shouted the Humbug, scribbling furiously on a piece of

paper.

“Well, I’m not sure, but—” Milo stammered after several minutes of

frantic figuring.

“You’ll have to do better than that,” scolded

the Dodecahedron, “or you’ll never know how far you’ve gone or whether

or not you’ve ever gotten there.”

“I’m not very good at problems,” admitted Milo.

“What a shame,” sighed the Dodecahedron. “They’re so very useful. Why,

did you know that if a beavei’ two feet long with a tail a foot and a

half long can build a dam twelve feet high and six feet wide in two

days, all you would need to build Boulder Dam is a beaver sixty-eight

feet long with a fifty-one foot tail?”

“Where would you find a beaver that big?” grumbled the Humbug as his

pencil point snapped.

“I’m sure I don’t know,” he replied, “but if you did, you’d certainly

know what to do with him.”

“That’s absurd,” objected Milo, whose head was spinning from all the

numbers and questions.

“That may be true,” he acknowledged, “but it’s completely accurate, and

as long as the answer is right, who cares if the question is wrong? If

you want sense, you’ll have to make it yourself.”

“All three roads arrive at the same place at the same time,” interrupted

Tock, who had patiently been doing the first problem.

“Correct!” shouted the Dodecahedron. “And I’ll take you there myself.”

He walked to the sign and quickly spun it around three times. As he did,

the three roads vanished and a new one suddenly appeared, heading in the

direction that the sign now pointed.

“Is every road five miles from Digitopolis?” asked Milo.

“I’m afraid it has to be,” the Dodecahedron replied, leaping onto the

back of the car. “It’s the only sign we’ve got.”

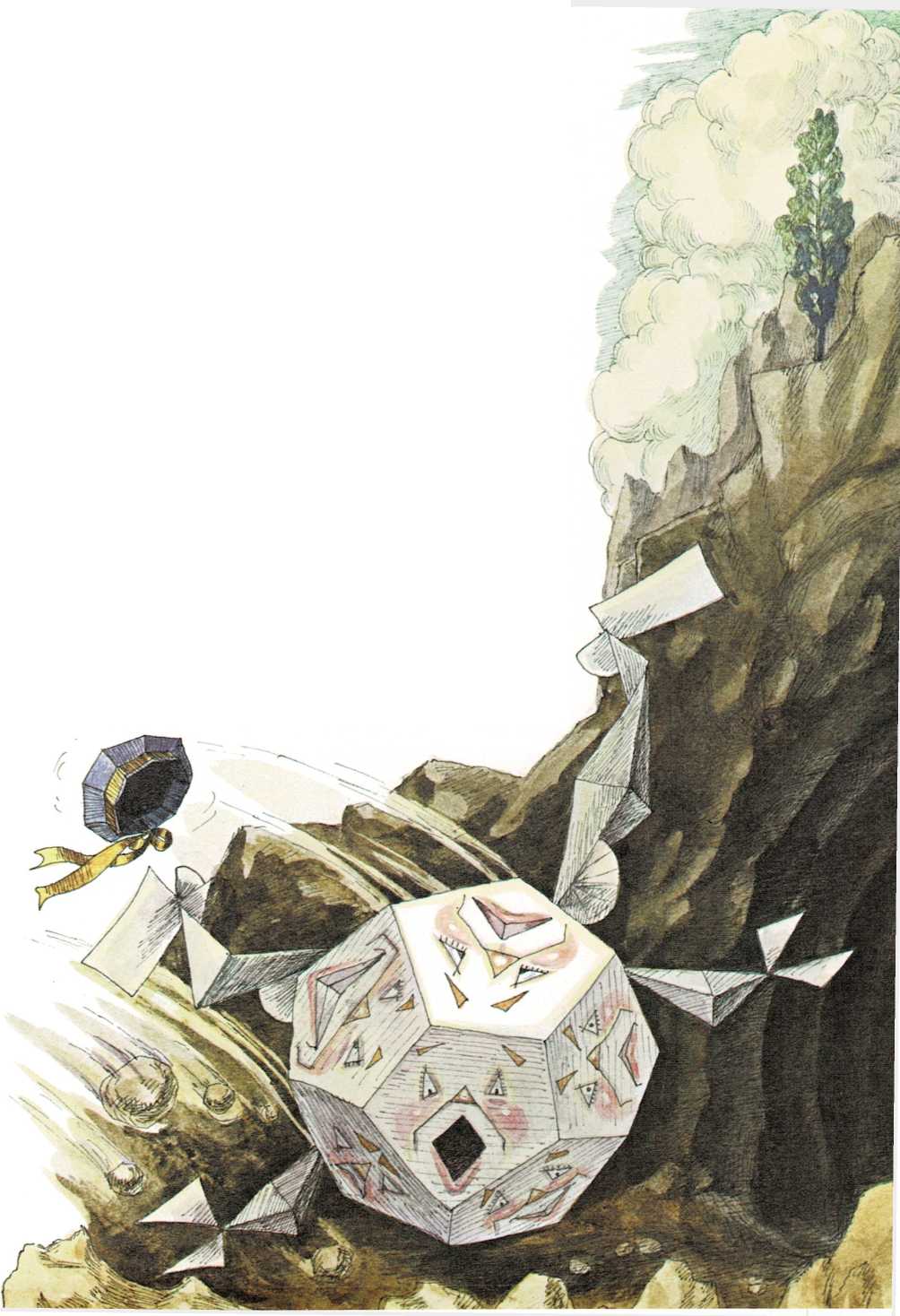

The new road was quite bumpy and full of stones, and each time they hit

one, the Dodecahedron bounced into the air and landed on one of his

faces, with a sulk or a smile or a laugh or a frown, depending upon

which one it was.

“We’ll soon be there,” he announced happily, after one of his short

flights. “Welcome to the land of numbers.”

“Is this the place where numbers are made?” asked Milo as the car

lurched again, and this time the Dodecahedron sailed off down the

mountainside, head over heels and grunt over grimace, until he landed

sad side up at what looked like the entrance to a cave.

“They’re not made,” he replied, as if nothing- had happened. “You have

to dig for them. Don’t you know anything at all about numbers?”

“Well, I don’t think they’re very important,” snapped Milo, too

embarrassed to admit the truth.

“NOT IMPORTANT!” roared the Dodecahedron, turning red with fury. “Could

you have tea for two without the two—or three blind mice without the

three? Would there be four corners of the earth if there weren’t a four?

And how would you sail the seven seas without a seven?”

“All I meant was—” began Milo, but the Dodecahedron, overcome with

emotion and shouting furiously, carried right on.

“If you had high hope\’s, how would you know how high they were? And did

you know that narrow escapes come in all different widths? Would you

travel the whole wide world without ever knowing how wide it was? And

how could you do anything at long last,” he concluded, waving his arms

over his head, “without knowing how long the last was? Why, numbers are

the most beautiful and valuable things in the world. Just follow me and

I’ll show you.” He turned on his heel and stalked off into the cave.

“Come along, come along,” he shouted from the dark hole. “I can’t wait

for you all day.” And in a moment they’d followed him into the mountain.

“Where are we going?” whispered Milo, for it seemed like the kind of

place in which you whispered.

“We’re here,” he replied with a sweeping gesture. “This is the numbers

mine.”

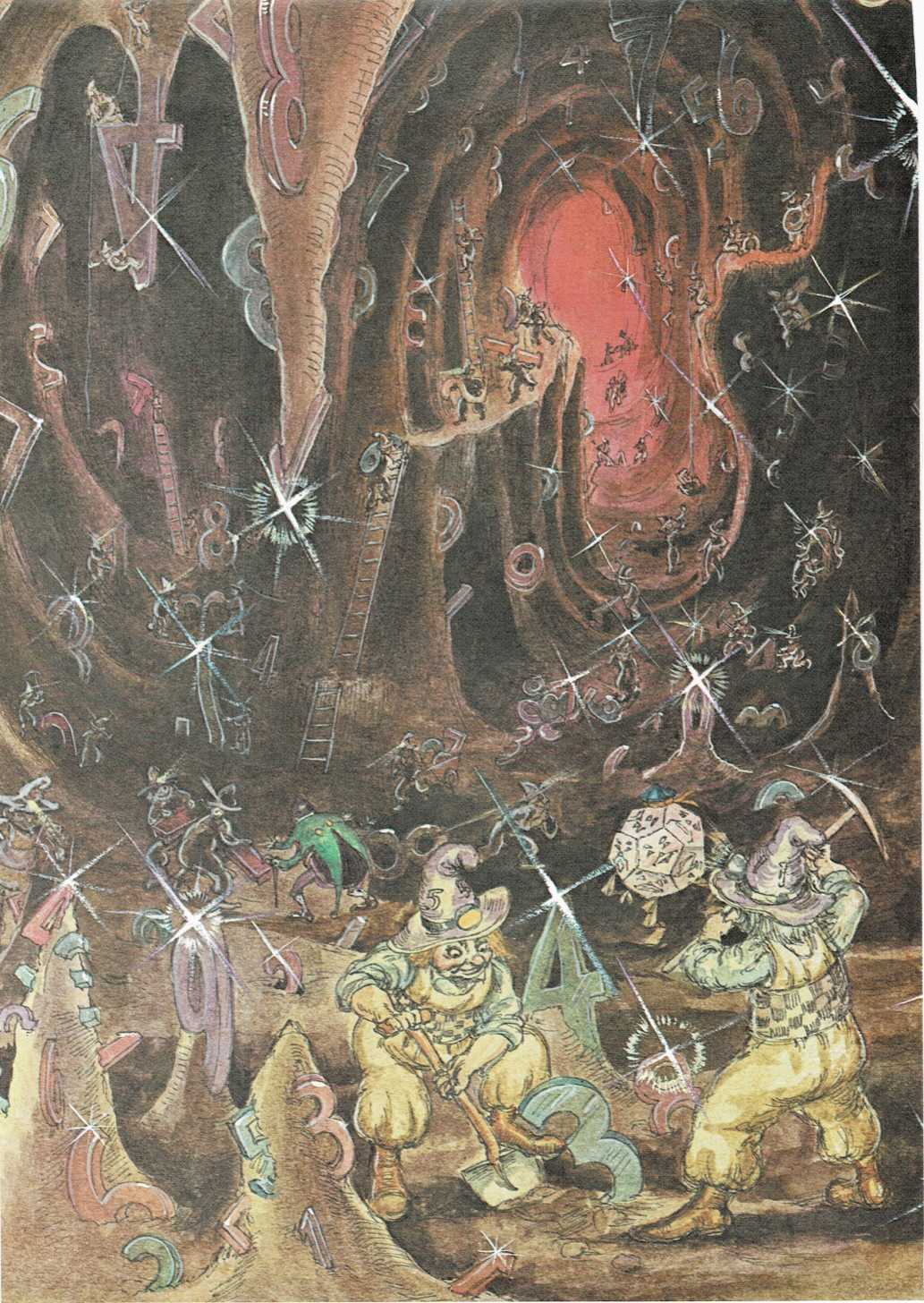

Milo squinted into the darkness and saw for the first time that they had

entered a vast cavern lit only by a soft, eerie glow from the great

stalactites which hung ominously from the ceiling.

Passages and corridors honeycombed the walls and wound their way from

floor to ceiling, up and down the sides of the cave. And, everywhere he

looked, Milo saw little men no bigger than himself busy digging and

chopping, shoveling and scraping, pulling and tugging carts full of

stone from one place to another.

“Right this way,” instructed the Dodecahedron, “and watch where you

step.”

“Whose mine is it?” asked Milo, stepping around two of the loaded

wagons.

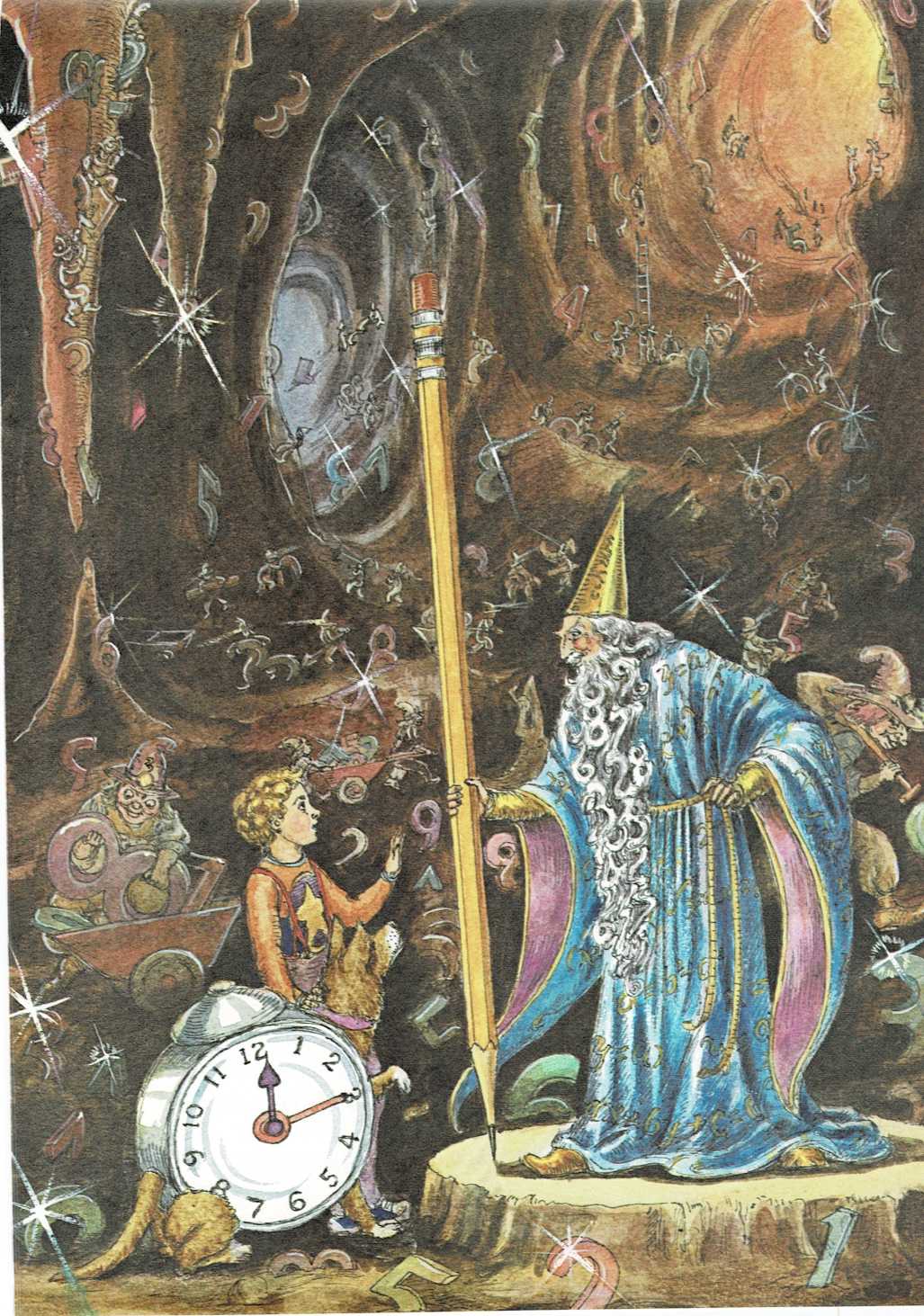

“BY THE FOUR MILLION EIGHT HUNDRED AND TWENTY-SEVEN THOUSAND SIX HUNDRED

AND FIFTY-NINE HAIRS ON MY HEAD, IT’S MINE, OF COURSE!” bellowed a voice

from across the cavern. And striding toward them came a figure who could

only have been the Mathemagician.

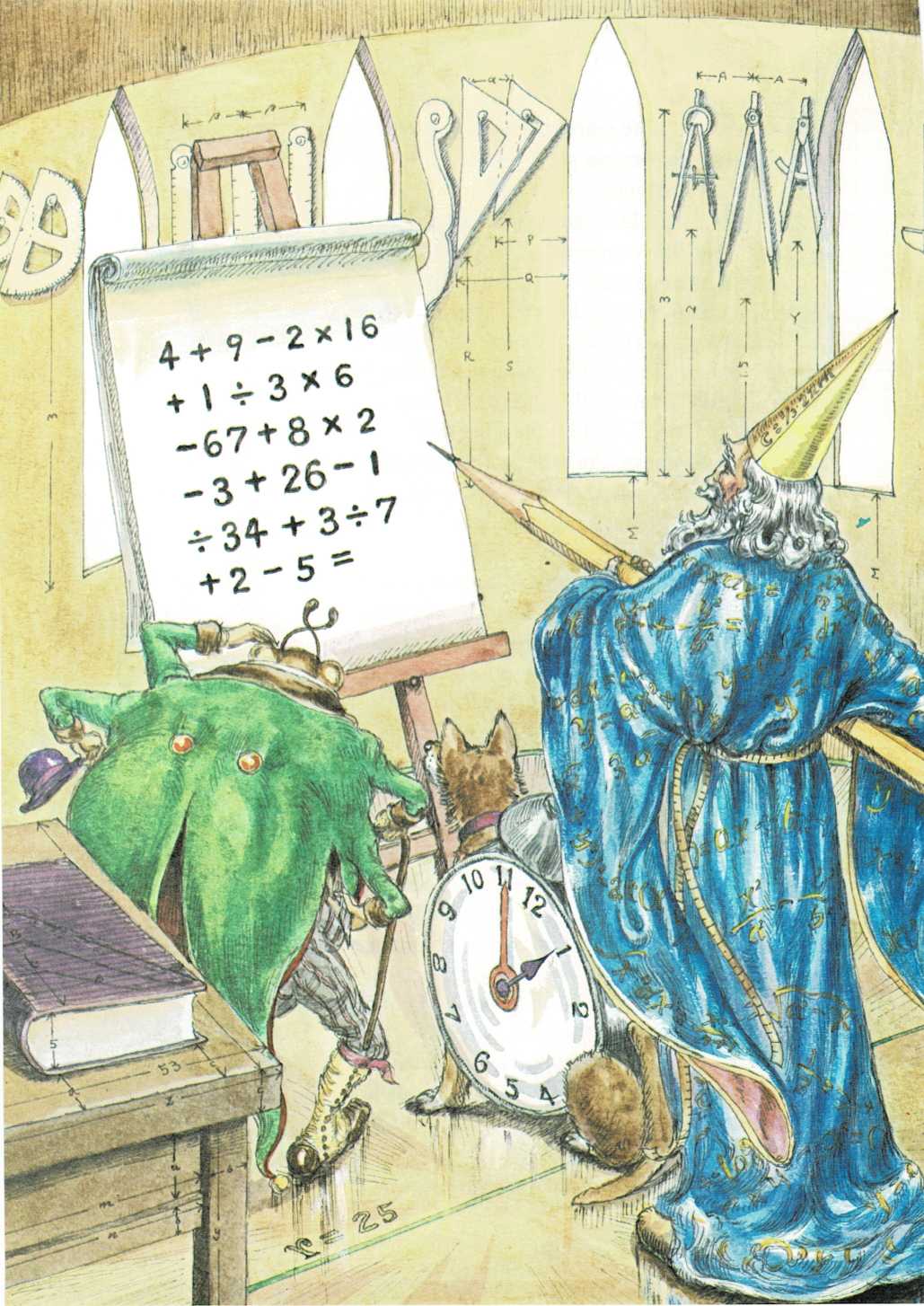

He was dressed in a long flowing robe covered entirely with complex

mathematical equations and a tall pointed cap that made him look very

wise. In his left hand he carried a long staff with a pencil point at

one end and a large rubber eraser at the other.

“It’s a lovely mine,” apologized the Humbug, who was always intimidated

by loud noises.

“The biggest number mine in the kingdom,” said the Mathemagician

proudly.

“Are there any precious stones in it?” asked Milo excitedly.

“PRECIOUS STONES!” he roared, even louder than before. And then he

leaned over toward Milo and whispered softly, “By the eight million two

hundred and forty-seven thousand three hundred and twelve threads in my

robe, I’ll say there are. Look here.”

He reached into one of the carts and pulled out a small object, which he

polished vigorously on his robe. When he held it up to the light, it

sparkled brightly.

“But that’s a five,” objected Milo, for that was certainly what it was.

“Exactly,” agreed the Mathemagician; “as valuable a jewel as you’ll find

anywhere. Look at some of the others.”

He scooped up a great handful of stones and poured them into Milo’s

arms. They included all the numbers from one to nine, and even an

assortment of zeros.

“We dig them and polish them right here,” volunteered the Dodecahedron,

pointing to a group of workers busily employed at the buffing wheels;

“and then we send them all over the world. Marvelous, aren’t they?”

“They are exceptional,” said Tock, who had a special fondness for

numbers.

“So that’s where they come from,” said Milo, looking in awe at the

glittering collection of numbers. He returned them to the Dodecahedron

as carefully as possible but, as he did, one dropped to the floor with a

smash and broke in two. The Humbug winced and Milo looked terribly

concerned.

“Oh, don’t worry about that,” said the Mathemagician as he scooped up

the pieces. “We use the broken ones for fractions.

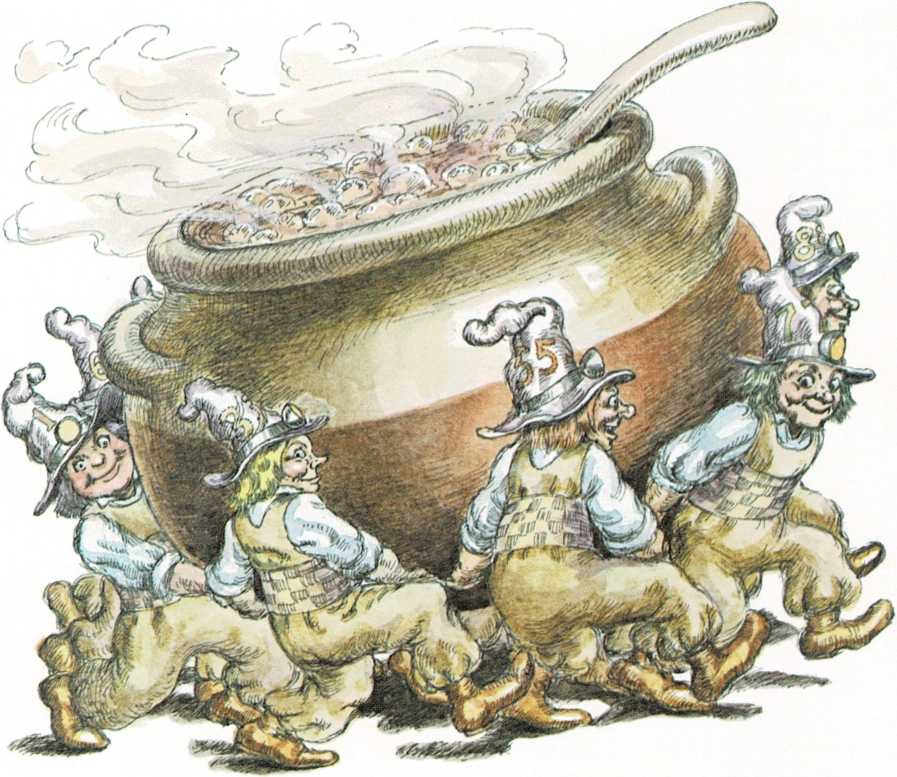

“Now,” he said, taking a silver whistle from his pocket and blowing it

loudly, “let’s have some lunch.”

Into the cavern rushed eight of the strongest miners carrying an immense

caldron which bubbled and sizzled and sent great clouds of savory steam

spiraling slowly to the ceiling.

“Perhaps you’d care for something to eat?” said the Mathemagician,

offering each of them a heaping bowlful.

“Yes, sir,” said Milo, who was beside himself with hunger.

“Thank you,” added Tock.

The Humbug made no reply, for he was already too busy eating, and in a

moment the three of them had finished absolutely everything they’d been

given.

“Please have another portion,” said the Mathemagician, filling their

bowls once more; and as quickly as they’d finished the first one the

second was emptied too.

“Do have some more,” suggested the Mathemagician, and they continued to

eat just as fast as he filled the plates.

“U-g-g-g-h-h-h,” gasped the bug, suddenly realizing that he was

twenty-three times hungrier than when he started, “I think I’m

starving.”

“Me, too,” complained Milo, whose stomach felt as empty as he could ever

remember; “and I ate so much.”

“Yes, it was delicious, wasn’t it?” agreed the pleased Dodecahedron,

wiping the gravy from several of his mouths. “It’s the specialty of the

kingdom—subtraction stew.”

“I have more of an appetite than when I began,” said Tock, leaning

weakly against one of the larger rocks.

“Certainly,” replied the Mathemagician; “what did you expect? The more

you eat, the hungrier you get. Everyone knows that.”

“They do?” said Milo doubtfully. “Then how do you ever get enough?”

“Enough?” he said impatiently. “Here in Digitopolis we have our meals

when we’re full and eat until we’re hungry. That way, when you don’t

have anything at all, you have more than enough. It’s a very economical

system. You must have been quite stuffed to have eaten so much.”

“It’s completely logical,” explained the Dodecahedron. “The more you

want, the less you get, and the less you get, the more you have. Simple

arithmetic, that’s all.”

“Oh dear,” said Milo sadly and softly. “I only eat when I’m hungry.”

“What a curious idea,” said the Mathemagician, raising his staff over

his head and scrubbing the rubber end back and forth several times on

the ceiling. “The next thing you’ll have us believe is that you only

sleep when you’re tired.” And by the time he’d finished the sentence,

the cavern, the miners, and the Dodecahedron had vanished, leaving just

the four of them standing in the Mathemagician’s workshop.

“I often find,” he casually explained to his dazed visitors, “that the

best way to get from one place to another is to erase everything and

begin again. Please make yourself at home.”

“Do you always travel that way?” asked Milo as he glanced curiously at

the strange circular room, whose sixteen tiny arched windows

corresponded exactly to the sixteen points of the compass. Around the

entire circumference were numbers from zero to three hundred and sixty,

marking the degrees of the circle, and on the floor, walls, tables,

chairs, desks, cabinets, and ceiling were labels showing their heights,

widths, depths, and distances to and from each other. To one side was a

gigantic note pad set on an artist’s easel, and from hooks and strings

hung a collection of scales, rulers, measures, weights, tapes, and all

sorts of other devices for measuring any number of things in every

possible way.

“No indeed,” replied the Mathemagician,

and this time he raised the sharpened end of his staff, drew a thin

straight line in the air, and then walked gracefully across it from one

side of the room to the other. “Most of the time I take the shortest

distance between any two points. And, of course, when I should be in

several places at once,” he remarked, writing carefully on the note pad,

“I simply multiply.”

Suddenly there were seven Mathemagicians standing side by side, and each

one looked exactly like the other.

“How did you do that?” gasped Milo.

“There’s nothing to it,” they all said in chorus, “if you have a magic

staff.” Then six of them canceled themselves out and simply disappeared.

“But it’s only a big pencil,” the Humbug objected, tapping at it with

his cane.

“True enough,” agreed the Mathemagician; “but once you learn to use it,

there’s no end to what you can do.”

“Can you make things disappear?” asked Milo.

“Why, certainly,” he said, striding over to the easel. “Just step a

little closer and watch carefully.”

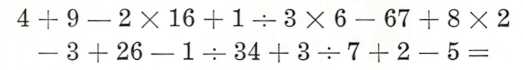

After demonstrating that there was nothing up his sleeves, in his hat,

or behind his back, he wrote quickly:

Then he looked up expectantly.

“Seventeen!” shouted the bug, who always managed to be first with the

wrong answer.

“It all comes to zero,” corrected Milo.

“Precisely,” said the Mathemagician,

making a very theatrical bow, and the entire line of numbers vanished

before their eyes. “Now is there anything else you’d like to see?” “Yes,

please,” said Milo. “Can you show me the biggest number there is?”

“I’d be delighted,” he replied, opening one of the closet doors. “We

keep it right here. It took four miners just to dig it out.”

Inside was the biggest

Milo had ever seen. It was fully twice as high as the Mathemagician.

“No, that’s not what I mean,” objected Milo.

“Can you show me the longest number there is?”

“Surely,” said the Mathemagician, opening another door. “Here it is. It

took three carts to carry it here.”

Inside this closet was the longest

imaginable. It was just about as wide as the three was high.

“No, no, no, that’s not what I mean either,” he said, looking helplessly

at Tock.

“I think what you would like to see,” said the dog, scratching himself

just under half-past four, “is the number of greatest possible

magnitude.”

“Well, why didn’t you say so?” said the Mathemagician, who was busily

measuring the edge of a raindrop. “What’s the greatest number you can

think of?”

“Nine trillion, nine hundred ninety-nine billion, nine hundred

ninety-nine million, nine hundred ninety-nine thousand, nine hundred

ninety-nine,” recited Milo breathlessly.

“Very good,” said the Mathemagician. “Now add one to it. Now add one

again,” he repeated when Milo had added the previous one. “Now add one

again. Now add one again. Now add one again, Now add one again. Now add

one again. Now add one again. Now add—“

“But when can I stop?” pleaded Milo.

“Never,” said the Mathemagician with a little smile, “for the number you

want is always at least one more than the number you’ve got, and it’s so

large that if you started saying it yesterday you wouldn’t finish

tomorrow.”

“Where could you ever find a number so big?” scoffed the Humbug.

“In the same place they have the smallest number there is,” he answered

helpfully; “and you know what that is.”

“One one-millionth?” asked Milo, trying to think of the smallest

fraction possible.

“Almost,” said the Mathemagician. “Now divide it in half. Now divide it

in half again. Now divide it in half again. Now divide it in half again.

Now divide it in half again. Now divide it in half again. Now divide—“

“Oh dear,” shouted Milo, holding his hands to his ears, “doesn’t that

ever stop either?”

“How can it,” said the Mathemagician, “when you can always take half of

whatever you have left until it’s so small that if you started to say it

right now you’d finish even before you began?”

“Where could you keep anything so tiny?” Milo asked, trying very hard to

imagine such a thing.

The Mathemagician stopped what he was doing and explained simply, “Why,

in a box

that’s so small you can’t see it—and that’s kept in a drawer that’s so

small you can’t see it, in a dresser that’s so small you can’t see it,

in a house that’s so small you can’t see it, on a street that’s so small

you can’t see it, in a city that’s so small you can’t see it, which is

part of a country that’s so small you can’t see it, in a world that’s so

small you can’t see it.”

Then he sat down, fanned himself with a handkerchief, and continued.

“Then, of course, we keep the whole thing in another box that’s so small

you can’t see it. If you follow me, I’ll show you where to find it.”

They walked to one of the small windows and there, tied to the sill, was

one end of a line that stretched along the ground and into the distance

until completely out of sight.

“Just follow that line forever,” said the Mathemagician, “and when you

reach the end, turn left. There you’ll find the land of Infinity, where

the tallest, the shortest, the biggest, the smallest, and the most and

the least of everything are kept.”

“I really don’t have that much time,” said Milo anxiously. “Isn’t there

a quicker way?”

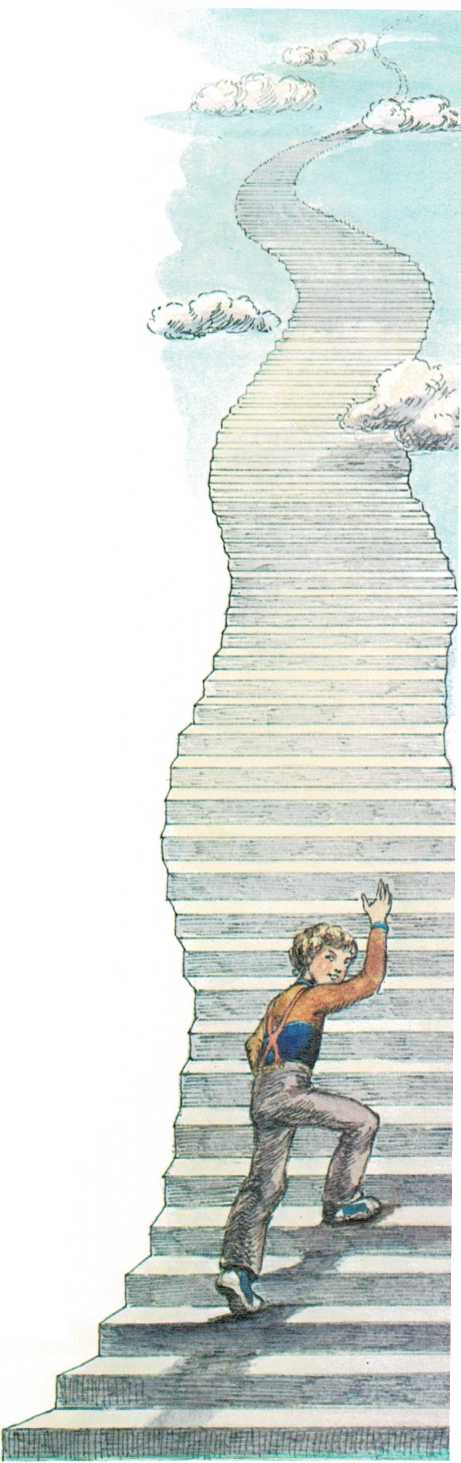

“Well, you might try this flight of stairs,” he suggested, opening

another door and pointing up. “It goes there, too.”

Milo bounded across the room and started up the stairs two at a time.

“Wait for me, please,” he shouted to Tock and the Humbug. “I’ll be gone

just a few minutes.”

You can follow Milo’s further adventures in the “Lands Beyond” in The

Phantom Tollbooth. Your public library probably has a copy of the book.