What makes these things work?

When you call a friend on the telephone, your voice doesn’t really

travel through the wire. Your friend hears a copy of your voice—a copy

made by electricity.

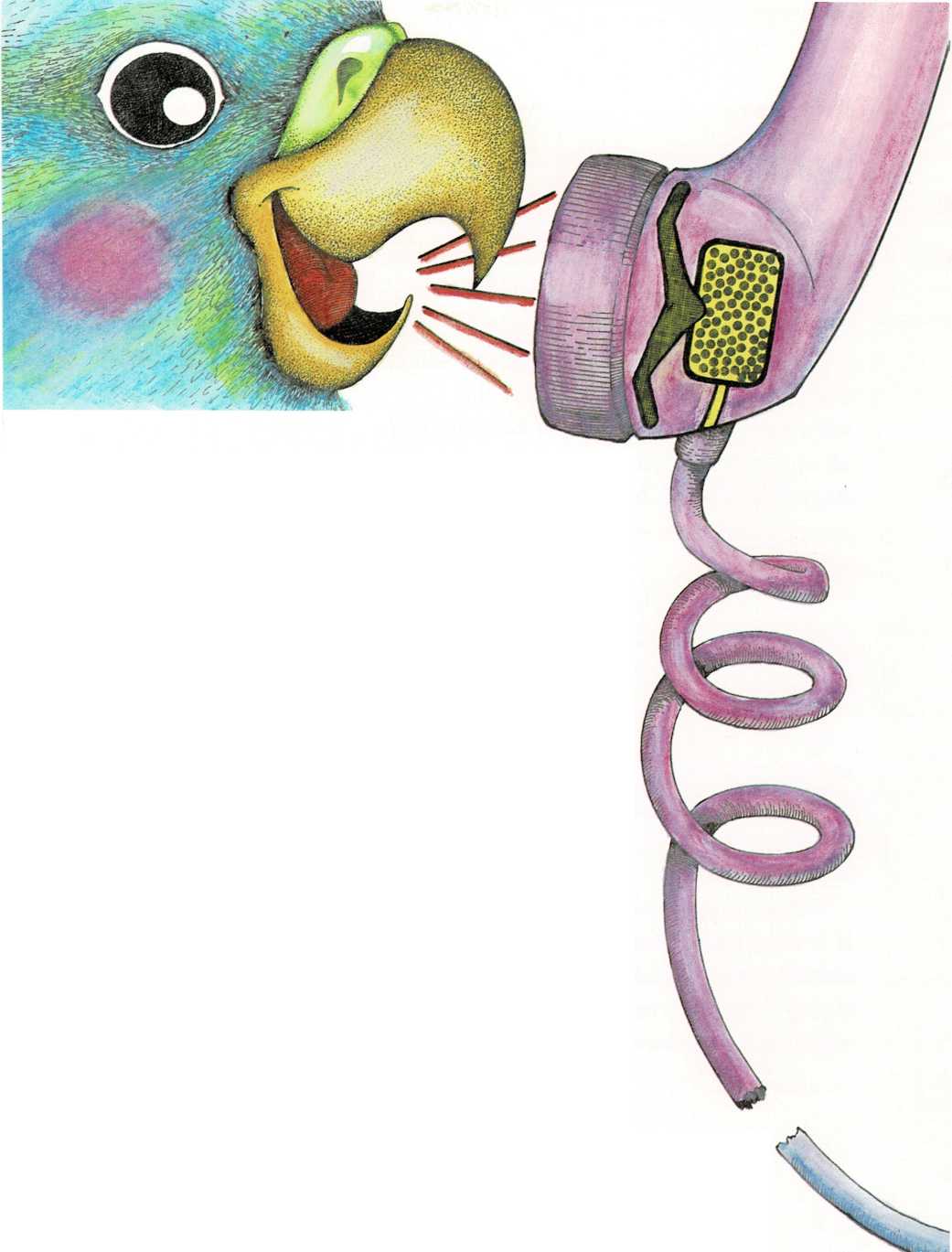

Inside the mouthpiece of your telephone there is a thin sheet of metal

called a diaphragm [(dy]{.smallcaps} uh fram). Behind the diaphragm

there is a small cup filled with grains of a black powdery chemical

called carbon.

The sound of your voice makes the diaphragm move in and out, or vibrate.

As it vibrates, it presses against the carbon grains—sometimes very

hard, sometimes very lightly.

Electricity passes through the carbon on its way through the telephone

wire. When the carbon grains are squeezed together, the current travels

through them easily. But

when the grains are spread apart, only a little

current can get through. So the vibrating

diaphragm causes strong or weak pushes of electricity to travel through

the telephone wire.

Inside the earpiece of your friend’s telephone is an electromagnet. When

the strong or weak pushes reach it, they cause this electromagnet to

make strong or weak pulls on another diaphragm. These pulls make the

diaphragm vibrate, producing sounds just like the ones you made. So your

friend hears a copy of what you said—a copy made by electricity in a

wire.

The music from a radio is an electric copy, too—a copy that travels by

air.

Microphones and other equipment at the radio station change sounds into

strong and weak electric signals. Then the signals are sent through the

air from the station to your radio.

When you tune in the station, the signals go to an electromagnet in the

radio speaker. The strong and weak pulls of the electromagnet cause

parts of the speaker to vibrate and produce the sounds you hear.