Stories

Harriet’s Secret

from Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh

Eleven-year-old Harriet wants to be a writer. To prepare for her future

career, she keeps a notebook in which she jots down what she sees and

thinks. The problem is that she gets her material by spying on people,

especially her friends at the private school she attends in New York.

And this leads to trouble.

That day, after school, everyone felt in a good mood because the weather

was suddenly gay and soft like spring. They hung around outside, the

whole class together, which was something they never did. Sport said

suddenly, “Hey, why don’t we go to the park and play tag?

Harriet was late for her spying, but she thought she would just play one

game and then leave. They all seemed to think this was a smashing idea,

so everyone filed across the street.

The kind of tag they played wasn’t very complicated; in fact Harriet

thought it was rather silly. The object seemed to be to run around in

circles and get very tired, then whoever was “it” tried to knock

everyone

else’s books out of their arms. They played and played. Beth Ellen was

eliminated at once, having no strength. Sport was the best. He managed

to knock down everyone’s books except Rachel Hennessey’s and Harriet’s.

He ran round and round then, very fast. Suddenly he knocked a few of

Harriet’s things off her arms, then Rachel tried to tease him away, and

Harriet started to run like crazy. Soon she was running and running as

fast as she could in the direction of the mayor’s house. Rachel was

right after her and Sport was close behind.

They ran and ran along the river. Then they were on the grass and Sport

fell down. It wasn’t any fun with him not chasing, so Rachel and Harriet

waited until he got up. Then he was very quick and got them.

All of Rachel’s books were on the ground, and some of Harriet’s. They

began to pick them up to go back and join the others.

Suddenly Harriet screeched in horror, “Where is my notebook?” They all

began looking around, but they couldn’t find it anywhere. Harriet

suddenly remembered that some things had been knocked down before they

ran away from the others. She began to run back toward them. She ran and

ran, yelling like a banshee the whole way.

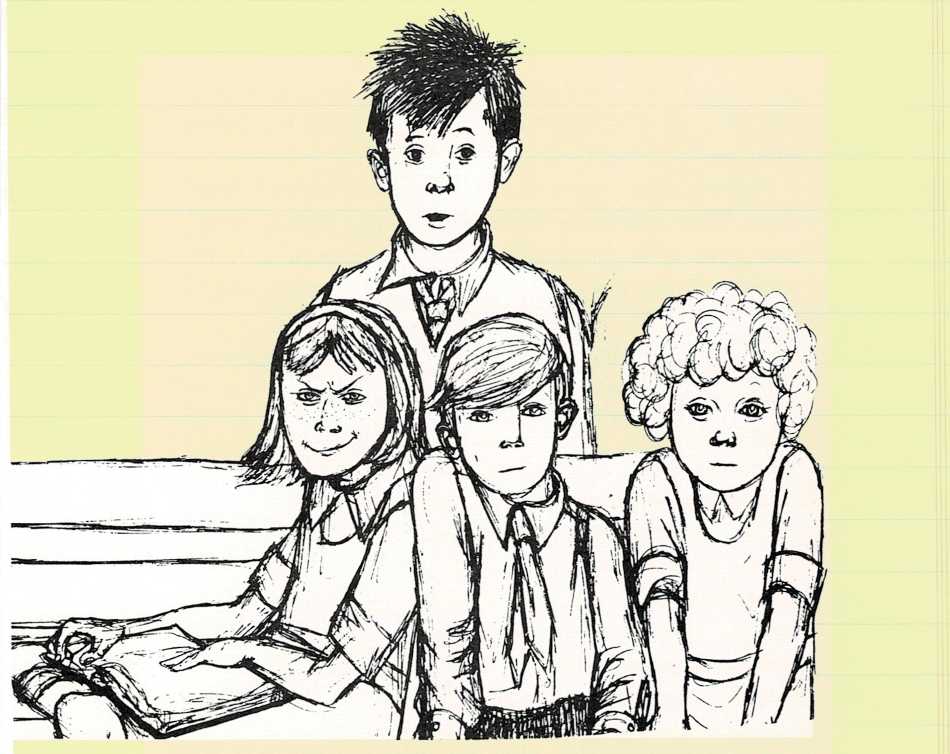

When she got back to where they had started she saw the whole

class—Beth Ellen, Pinky Whitehead, Carrie Andrews, Marion Hawthorne,

Laura Peters, and The Boy with the Purple Socks—all sitting around a

bench while Janie Gibbs read to them from the notebook.

Harriet descended upon them with a scream that was supposed to frighten

Janie so much she would drop the book. But Janie didn’t frighten easily.

She just stopped reading and looked up calmly. The others looked up too.

She looked at all their eyes and suddenly Harriet M. Welsch was afraid.

They just looked and looked, and their eyes were the meanest eyes she

had ever seen. They formed a little knot and wouldn’t let her near them.

Rachel and Sport came up then. Marion Hawthorne said fiercely, “Rachel,

come over here.” Rachel walked over to her, and after Marion had

whispered in her ear, got the same mean look.

Janie said, “Sport, come over here.”

“Whadaya mean?” said Sport.

“I have something to tell you,” Janie said in a very pointed way.

Sport walked over and Harriet’s heart went into her sneakers. “FINKS!”

Harriet felt rather hysterical. She didn’t know what that word meant,

but since her father said it all the time, she knew it was bad.

Janie passed the notebook to Sport and Rachel,

never taking her eyes off Harriet as she did so. “Sport, you’re on page

thirty-four; Rachel, you’re on fifteen,” she said quietly.

Sport read his and burst into tears. “Read it aloud, Sport,” said Janie

harshly.

“I can’t.” Sport hid his face.

The book was passed back to Janie. Janie read the passage in a solemn

voice.

Sometimes I can’t stand Sport. With his worrying all the time and

fussing over his father, sometimes he’s like a little old woman.

Sport turned his back on Harriet, but even from his back Harriet could

see that he was crying.

“That’s not fair,” she screamed. “There’re some nice things about

Sport in there.”

Everyone got very still. Janie spoke very quietly. “Harriet, go over

there on that bench until we decide what we’re going to do to you.”

Harriet went over and sat down. She couldn’t hear them. They began to

discuss something rapidly with many gestures. Sport kept his back turned

and Janie never took her eyes off Harriet, no matter who was talking.

Harriet thought suddenly, I don’t have to sit here. And she got up and

marched off in as dignified a way as possible under the circumstances.

They were so busy they didn’t even seem to notice her.

At home, eating her cake and milk, Harriet reviewed her position. It was

terrible. She decided that she had never been in a worse position. She

then decided she wasn’t going to think about it anymore. She went to bed

in the middle of the afternoon and didn’t get up until the next morning.

Her mother thought she was sick and said to her father, “Maybe we ought

to call the doctor.”

“Finks, all of them,” said her father. Then they went away and Harriet

went to sleep.

In the park all the children sat around and read things aloud. These are

some of the things they read:

Notes on what Carrie Andrews thinks of Marion Hawthorne

Thinks: Is mean

Is rotten in math Has funny knees Is a pig

Then:

If Marion Hawthorne doesn\’t watch out she\’s going to grow up into a

lady Hitler.

Janie Gibbs smothered a laugh at that one but not at the next one:

Who does Janie Gibbs think, she’s kidding? Does she really think she

could ever be a scientist?

Janie looked as though she had been struck. Sport looked at her

sympathetically. They looked at each other, in fact, in a long,

meaningful way.

Janie read on:

What to do about Pinky Whitehead

Turn the hose on him.

Pinch his ears until he screams.

Tear his pants off and laugh at him.

Pinky felt like running. He looked around nervously, but Harriet was

nowhere to be seen.

There was something about everyone.

Maybe Beth Ellen doesn’t have any parents. I asked her her mother’s

name and she couldn’t remember. She said she had only seen her once and

she didn’t remember it very well. She wears strange things like orange

sweaters and a big black car comes for her once a week and she goes

someplace else.

Beth Ellen rolled her big eyes and said nothing. She never said

anything, so this wasn’t unusual.

The reason Sport dresses so funny is that his father won’t buy him

anything to wear because his mother has all the money.

Sport turned his back again.

Today a new boy arrived. He is so dull no one can remember his name so

I have named him The Boy with the Purple Socks. Imagine. Where would he

ever find purple socks?

The Boy with the Purple Socks looked down at his purple socks and

smiled.

Everyone looked at the sock boy. Carrie spoke up. She had a rather

grating voice. “What IS your name?” even though by now they all knew

perfectly well.

“Peter,” he said shyly.

“Why do you wear purple socks?” asked Janie.

Peter smiled shyly, looked at his socks, then said, “Once, at the

circus, my mother lost me. She said, after that, if I had on purple

socks, she could always find me.”

“Hmmmmm,” said Janie.

Gathering courage from this, Peter spoke again. “She wanted to make it

a whole purple suit, but I rebelled.”

“I don’t blame you,” said Janie.

Peter bobbed his head and grinned. They all grinned back at him because

he had a tooth missing and looked rather funny, but also he wasn’t a bad

sort, so they all began to like him a little bit.

They read on:

Miss Elson has a wart behind her elbow;

This was fairly boring so they skipped ahead.

I once saw Miss Elson when she didn’t see me and she was picking her

nose.

That was better, but still they wanted to read about themselves.

Carrie Andrews’ mother has the biggest front I ever saw.

There was a great deal of tension in the group after this last item.

Then Sport gave a big horselaugh, and Pinky Whitehead’s ears turned

bright red. Janie smiled a fierce and frightening smile at Carrie

Andrews, who looked as though she wanted to dive under the bench.

When I grow up I’m going to find out everything about everybody and put

it all in a book. The book is going to

etc Liie ntAi une.

be called Secrets by Harriet M. Welsch. I will also have photographs

in it and maybe some medical charts if I can get them.

Rachel stood up, “I have to go home. Is there anything about me?”

They flipped through until they found her name.

I don\’t know exactly if I like Rachel or whether it is just that I

like going to her house because her mother makes homemade cake. If I had

a club I’m not sure I would have Rachel in it.

“Thank you,” Rachel said politely and left for home.

Laura Peters left too after the last item:

If Laura Peters doesn’t stop smiling at me in that wishy-washy way I’m

going to give her a good kick.

The next morning when Harriet arrived at school no one spoke to her.

They didn’t even look at her. It was exactly as though no one at all had

walked into the room. Harriet sat down and felt like a lump. She looked

at everyone’s desk, but there was no sign of the notebook. She looked at

every face and on every face was a plan, and on each face was the same

plan. They had organization. I’m going to get it, she thought grimly.

That was not the worst of it. The worst was that even though she knew

she shouldn’t, she had stopped by the stationery store on the way to

school and had bought another notebook. She had tried not to write in

it, but she was such a creature of habit that even now she found herself

taking it out of the pocket of her jumper, and furthermore, the next

minute she was scratching in a whole series of things.

They are out to get me. The whole room is filled with mean eyes. I

won’t get through the day. I might throw up my tomato sandwich. Even

Sport and Janie. What did I say about Janie? I don’t remember. Never

mind. They may think I am a weakling but a spy is trained for this kind

of fight. I am ready for them.

She went on scratching until Miss Elson cleared her throat, signifying

she had entered the room. Then everyone stood up as they always did,

bowed, said, “Good morning, Miss Elson,” and sat back down. It was the

custom at this moment for everyone to punch each other. Harriet looked

around for someone to do some poking with, but they all sat stony-faced

as though they had never poked anyone in their whole lives.

It made Harriet feel better to try and quote like Ole Golly,[^3] so she

wrote:

The sins of the fathers

That was all she knew from the Bible besides the shortest verse: “Jesus

wept.”

Class began and all was forgotten in the joy of writing Harriet M.

Welsch at the top of the page.

Halfway through the class Harriet saw a tiny piece of paper float to the

floor on her right. Ah-ha, she thought, the chickens; they are making up

already. She reached down to get the note. A hand flew past her nose and

she realized that the note had been retrieved in a neat backhand by

Janie who sat to the right of her.

Well, she thought, so it wasn’t for me, that’s all. She looked at

Carrie, who had sent the note, and Carrie looked carefully away without

even giggling.

Harriet wrote in her notebook:

Carrie Andrews has an ugly pimple right next to her nose.

Feeling better, she attacked her homework with renewed zeal. She was

getting hungry. Soon she would have her tomato sandwich. She looked up

at Miss Elson who was looking at Marion Hawthorne who was scratching her

knee. As Harriet looked back at her work she suddenly saw a glint of

white sticking out of Janie’s jumper pocket. It was the note! Perhaps

she could just reach over ever so quietly and pull back very quickly.

She had to see.

She watched her own arm moving very quietly over, inch by inch. Was

Carrie Andrews watching? No. Another inch. Another. There!! She had

it. Janie obviously hadn’t felt a thing. Now to read! She looked at Miss

Elson but she seemed to be in a dream. She unfolded the tiny piece of

paper and read:

Harriet M. Welsch smells. Don’t you think so?

Oh, no! Did she really smell? What of? Bad, obviously. Must be very bad.

She held up her hand and got excused from class. She went into the

bathroom and smelled herself all over, but she couldn’t smell anything

bad. Then she washed her hands and face. She was going to leave, then

she went back and washed her feet just in case. Nothing smelled. What

were they talking about? Anyway, now, just to be sure, they would smell

of soap.

When she got back to her desk, she noticed a little piece of paper next

to where her foot would ordinarily be when she sat down. Ah, this will

explain it, she thought. She made a swift move, as though falling, and

retrieved the note without Miss Elson seeing. She unrolled it eagerly

and read:

There is nothing that makes me sicker than watching Harriet M. Welsch

eat a tomato sandwich.

Pinky Whitehead

The note must have misfired. Pinky sat to the right and it was addressed

to Sport, who sat on her left.

What was sickening about a tomato sandwich? Harriet felt the taste in

her mouth. Were they crazy?

It was the best taste in the world. Her mouth watered at the memory of

the mayonnaise. It was an experience, as Mrs. Welsch was always saying.

How could it make anyone sick? Pinky Whitehead was what could make you

sick. Those stick legs and the way his neck seemed to swivel up and down

away from his body. She wrote in her notebook:

There is no rest for the weary.

As she looked up she saw Marion Hawthorne turn swiftly in her direction.

Then suddenly she was looking full at Marion Hawthorne’s tongue out at

her, and a terribly ugly face around the tongue, with eyes all screwed

up and pulled down by two fingers so that the whole thing looked as

though Marion Hawthorne were going to be carted away to the hospital.

Harriet glanced quickly at Miss Elson. Miss Elson was dreaming out the

window. Harriet wrote quickly:

How unlike Marion Hawthorne. I don’t think she ever did anything bad.

Then she heard the giggles. She looked up. Everyone had caught the look.

Everyone was giggling and laughing with Marion, even Sport and Janie.

Miss Elson turned around and every face went blank, everybody bent again

over the desks. Harriet wrote quietly.

Perhaps I can talk to my mother about changing schools. I have the

feeling this morning that everyone in this school is insane. I might

possibly bring a ham sandwich tomorrow but I have to think about it.

The lunch bell rang. Everyone jumped as though they had one body and

pushed out the door. Harriet jumped too, but for some reason or other

three people bumped into her as she did. It was so fast she didn’t even

see who it was, but the way they did it she was pushed so far back that

she was the last one out the door. They all ran ahead, had gotten their

lunchboxes, and were outside by the time she got to the cloakroom. It’s

true that she was detained because she had to make a note of the fact

that Miss Elson went to the science room to talk to Miss Maynard, which

had never happened before in the history of the school.

When she picked up her lunch the bag felt very light. She reached inside

and there was only crumpled paper. They had taken her tomato sandwich.

They had taken her tomato sandwich. Someone had taken it. She

couldn’t get over it. This was completely against the rules of the

school. No one was supposed to steal your tomato sandwich. She had been

coming to this school since she was four—let’s see, that made seven

years—and in all those seven years no one had ever taken her tomato

sandwich. Not even during those six months when she had brought pickle

sandwiches with mustard. No one had even asked for so much as a bite.

Sometimes Beth Ellen passed around olives because no one else had olives

and they were very chic, but that was the extent of the sharing. And now

here it was noon and she had nothing to eat.

She was aghast. What could she do? It would be ridiculous to go around

asking “Has anyone seen a tomato sandwich?” They were sure to laugh. She

would go to Miss Elson. No, then she would be a ratter, a squealer, a

stoolie. Well, she couldn’t starve. She went to the telephone and asked

to use it because she had forgotten her lunch. She called and the cook

told her to come home, that she would make another tomato sandwich in

the meantime.

Harriet left, went home, ate her tomato sandwich, and took to her bed

for another day. She had to think. Her mother was playing bridge

downtown. She pretended to be sick enough so the cook didn’t yell at her

and yet not sick enough for the cook to call her mother. She had to

think.

As she lay there in the half gloom she looked out

over the trees in the park. For a while she watched a bird, then an old

man who walked like a drunk. Inside she felt herself thinking “Everybody

hates me, everybody hates me.”

At first she didn’t listen to it and then she heard what she was

feeling. She said it several times to hear it better. Then she reached

nervously for her notebook and wrote in big, block letters, the way she

used to write when she was little.

EVERYBODY HATES ME.

She leaned back and thought about it. It was time for her cake and milk,

so she got up and went downstairs in her pajamas to have it. The cook

started a fight with her, saying that if she were sick she couldn’t have

any cake and milk.

Harriet felt big hot tears come to her eyes and she started to scream.

The cook said calmly, “Either you go to school and you come home and

have your cake and milk, or you are sick and you don’t get cake and milk

because that’s no good for you when you’re sick; but you don’t lie

around up there all day and then get cake and milk.”

“That’s the most unreasonable thing I ever heard of,” Harriet screamed.

She began to scream as loud as she could. Suddenly she heard herself

saying over and over again, “I hate you, I hate you, I hate you.” Even

as she did it she knew she didn’t really hate the cook; in fact, she

rather liked her, but it seemed to her that at that moment she hated

her.

The cook turned her back and Harriet heard her mutter, “Oh, you, you

hate everybody.”

This was too much. Harriet ran to her room. She did not hate everybody.

She did not. Everybody hated her, that’s all. She crashed into her room

with a bang, ran to her bed, and smashed her face down into the pillow.

After she was tired of crying, she lay there and looked at the trees.

She saw a bird and began to hate

the bird. She saw the old drunk man and felt such hatred for him she

almost fell off the bed. Then she thought of them all and she hated them

each and every one in turn: Carrie Andrews, Marion Hawthorne, Rachel

Hennessey, Beth Ellen Hansen, Laura Peters, Pinky Whitehead, the new one

with the purple socks, and even Sport and Janie, especially Sport and

Janie.

She just hated them. I hate them, she thought. She picked up her

notebook:

When I am big I will be a spy. I will go to one country and I will find

out its secrets and then I will go to another country and tell them and

then find out their secrets and I will go back to the first one and rat

on the second and I will go to the second and rat on the first. I will

be the best spy there ever was and I will know everything. Everything.

As she began to fall asleep she thought, And then they’ll all be

petrified of me.

Harriet was sick for three days. That is, she lay in bed for three days.

Then her mother took her to see the kindly old family doctor. He used to

be a kindly old family doctor who made house calls, but now he wouldn’t

anymore. One day he had stamped his foot at Harriet’s mother and said,

“I like my office and I’m going to stay in it. I pay so much rent on

this office that if I leave it for five minutes my child misses a year

of school. I’m never coming out again.” And from that moment on he

didn’t. Harriet rather respected him for it, but his stethoscope was

cold.

When he had looked Harriet all over, he said to her mother, “There isn’t

a blessed thing wrong with her.”

Harriet’s mother gave her a dirty look, then sent her out into the outer

office. As Harriet closed the door behind her she heard the doctor

saying, “I think I know what’s the matter with her. Carrie told us some

long story about a notebook.”

Harriet stopped dead in her tracks. “That’s right,” she said out loud to

herself. “His name is Dr. Andrews, so he’s Carrie Andrews’ father.”

She got out her notebook and wrote it down. Then she wrote:

I wonder why he doesn’t cure that pimple on Carrie’s nose?

“Come on, young lady, we’re going home.” Harriet’s mother took her by

the hand. She looked as though she might take Harriet home and kill her.

As it turned out, she didn’t. When they got home, she said briskly, “All

right, Harriet the Spy, come into the library and talk to me.”

Harriet followed her, dragging her feet. She wished she were Beth Ellen

who had never met her mother.

“Now, Harriet, I hear you’re keeping dossiers on everyone in school.”

“What’s that?” Harriet had been prepared to deny everything but this was

a new one.

“You keep a notebook?”

“A notebook?”

“Well, don’t you?”

“Why?”

“Answer me, Harriet.” It was serious.

“Yes.”

“What did you put in it?”

“Everything.”

“Well, what kind of thing?”

“Just… things.”

“Harriet Welsch, answer me. What do you write about your classmates?”

“Oh, just… well, things I think…. Some nice things … and—and

mean things.”

“And your friends saw it?”

“Yes, but they shouldn’t have looked. It’s private. It even says PRIVATE

all over the front of it.”

“Nevertheless, they did. Right?”

“Yes.”

“And then what happened?”

“Nothing.”

“Nothing?” Harriet’s mother looked very skeptical.

“Well… my tomato sandwich disappeared.”

“Don’t you think that maybe all those mean things made them angry?”

Harriet considered this as though it had never entered her mind. “Well,

maybe, but they shouldn’t have looked. It’s private property.”

“That, Harriet, is beside the point. They did. Now why do you think

they got angry?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well…” Mrs. Welsch seemed to be debating whether to say what she

finally did. “How did you feel when you got some of those notes?”

There was a silence. Harriet looked at her feet. “Harriet?” Her mother

was waiting for an answer. “I think I feel sick again. I think I’ll go

to bed.” “Now, darling, you’re not sick. Just think about it a moment.

How did you feel?”

Harriet burst into tears. She ran to her mother and cried very hard. “I

felt awful. I felt awful,” was all she could say. Her mother hugged her

and kissed her a lot. The more she hugged her the better Harriet felt.

She was still being hugged when her father came home. He hugged her too,

even though he didn’t know what it was all about. After that they all

had dinner and Harriet went up to bed.

How do you think Harriet will work out her problems?

You can find out by reading the book, Harriet the Spy, by Louise

Fitzhugh. And you can follow her further adventures in The Long

Secret. Another book you will enjoy is The Secret Language by Ursula

Nordstrom. It is about two girls at a boarding school and the “secret

language” they share.