A Thousand Pails of Water

by Ronald Roy

Yukio lived in a village where people fished and hunted whales to make

their living.

Yukio’s father, too, was a whale hunter.

“Why do you kill the whales, Father?” Yukio asked. “Suki’s father works

in the market and his hands are never red from blood.”

“Hunting the whale is all I know,” his father answered.

But Yukio did not understand.

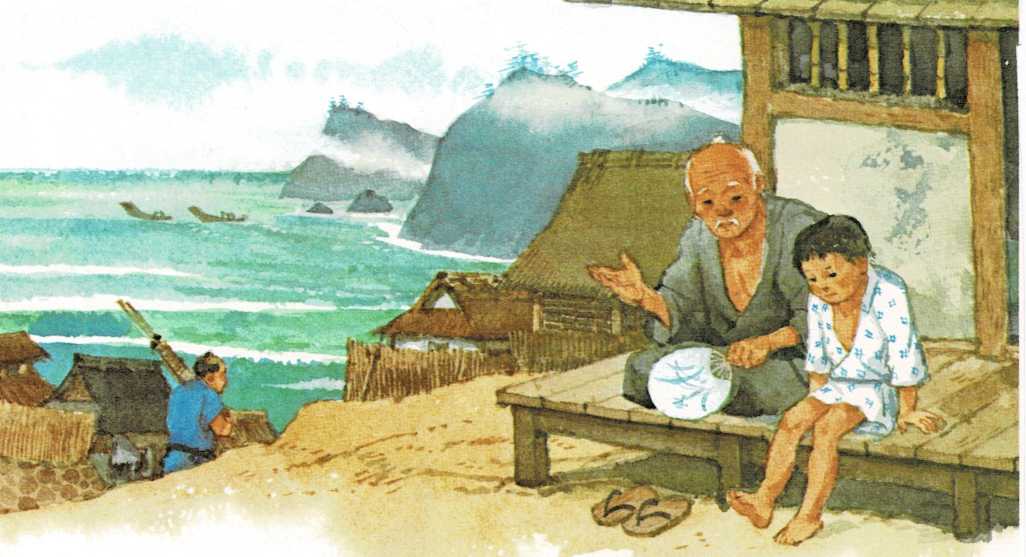

Yukio went to his grandfather and asked again. “Why does my father kill

the whales?”

“Your father does what he must do,” his grandfather said. “Let him be,

little one, and ask your questions of the sea.”

So Yukio went to the sea.

Small creatures scurried from under his feet in the tide pools. Large

scavenger birds screamed at him from the sky, “Bring us food!”

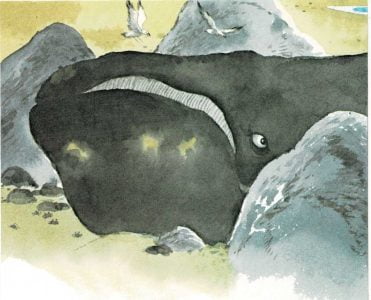

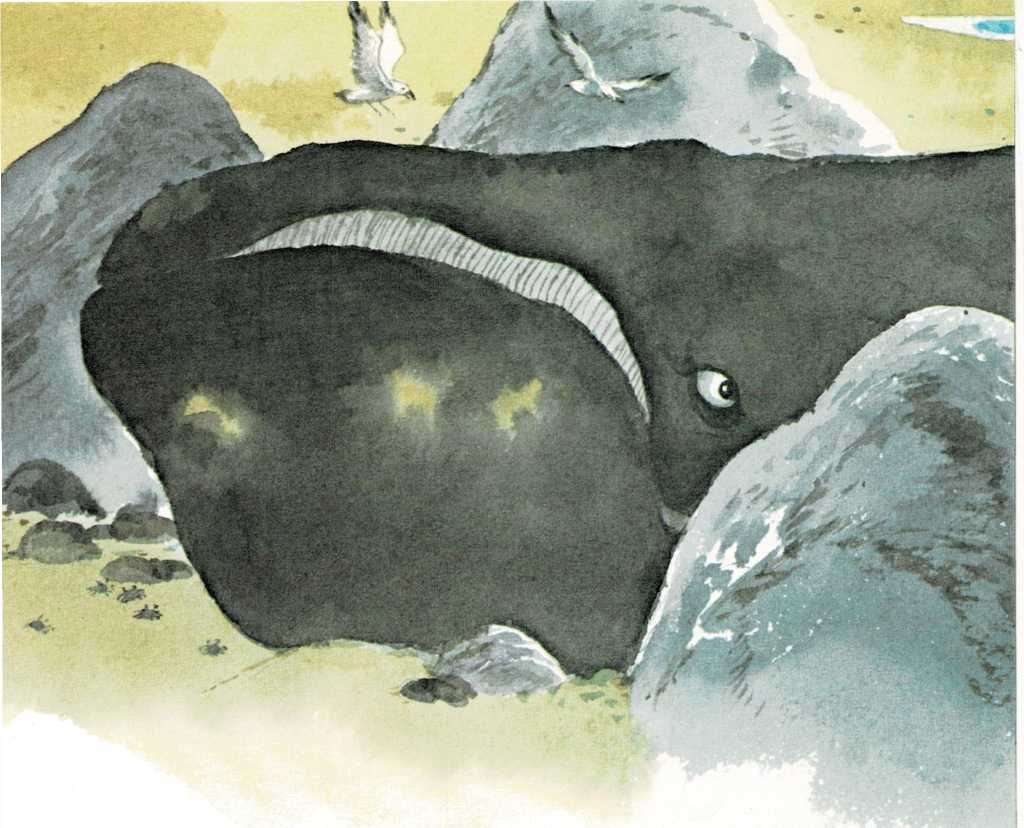

Then Yukio saw a whale that had become lodged between some rocks and was

left behind when the tide went out.

The large tail flukes beat the sand, helplessly. The eye, as big as

Yukio’s hand, rolled in fright.

Yukio knew that the whale would not live long out of the sea.

“I will help you, sir,” he said.

But how? The whale was huge, like a temple.

Yukio raced to the water’s edge. Was the tide coming in or going out?

In, he decided, by the way the little fingers of foam climbed higher

with each new wave.

The sun was hot on Yukio’s back as he stood looking at the whale.

Yukio filled his pail with water and threw it over the great head.

“You are so big and my pail is so small!” he cried. “But I will throw a

thousand pails of water over you before I stop.”

The second pail went on the head as well, and the third and the fourth.

But Yukio knew he must wet every part of the whale or it would die in

the sun.

Yukio made many trips to the sea for water, counting as he went. He

threw four pails on the body, then four on the tail, and then three on

the head.

There was a little shade on one side of the big gray prisoner. Yukio sat

there, out of breath, his heart pounding. Then he looked in the whale’s

eye and remembered his promise.

Yukio went back to the sea and stooped to fill his pail. How many had he

filled so far? He had lost count. But he knew he must not stop.

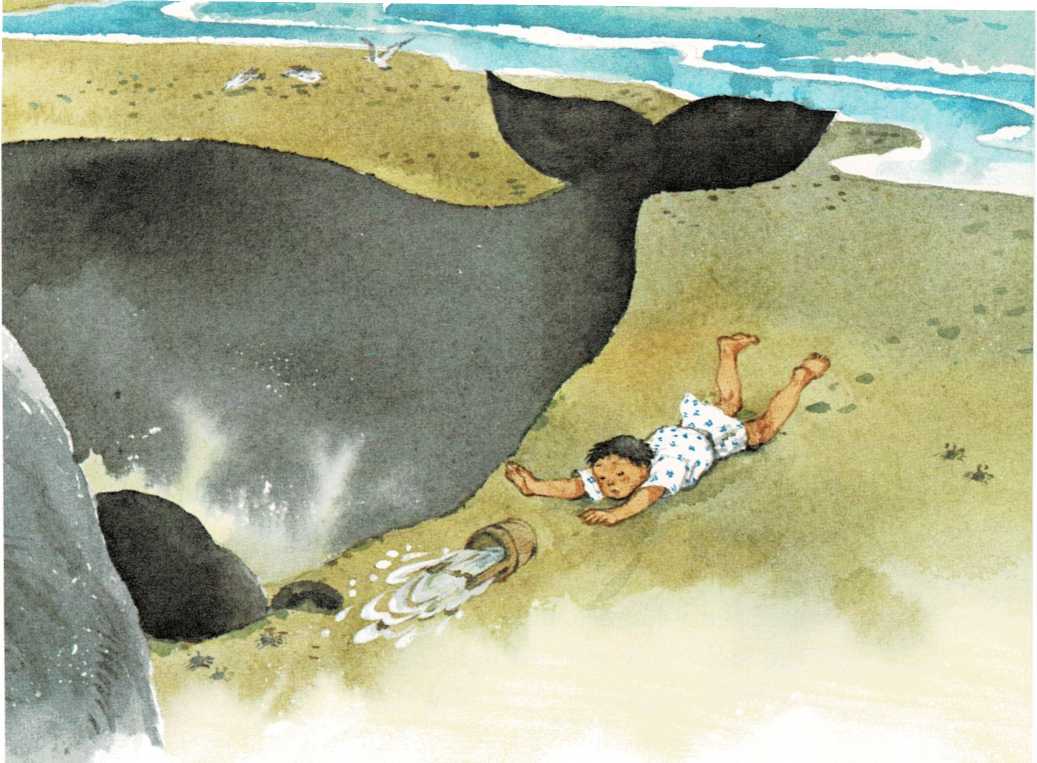

Yukio fell, the precious water spilling from his pail. He cried, and his

tears disappeared into the sand.

A wave touched his foot, as if to say, “Get up and carry more water. I

am coming, but I am very slow.”

Yukio filled his pail over and over. His back hurt, and his arms—but

he threw and threw.

He fell again, but this time he did not get up.

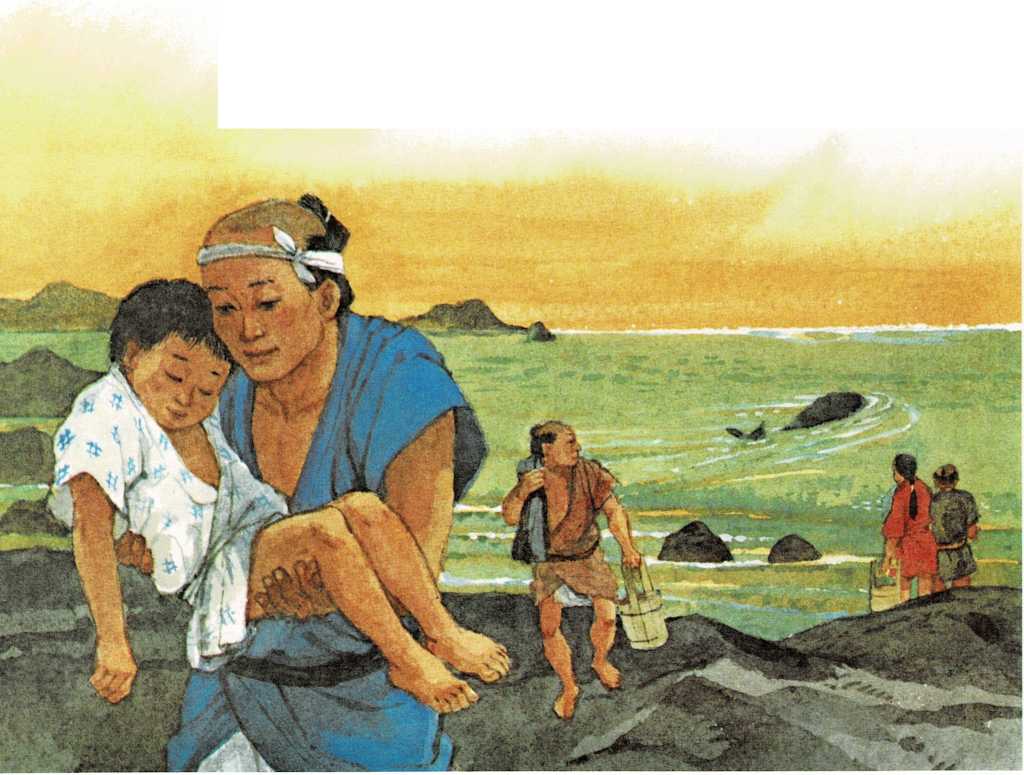

Yukio felt himself being lifted.

“You have worked hard, little one. Now let us help.”

Yukio’s grandfather lay him in the shade of one of the rocks. Yukio

watched his grandfather throw his first pail of water and go for

another.

“Hurry!” Yukio wanted to scream, for his grandfather was old and walked

slowly.

Then Yukio heard the voices. His father and the village people were

running toward the sea. They carried pails and buckets and anything that

would hold water.

Some of the villagers removed their jackets and soaked them in the sea.

These they placed on the whale’s burning skin. Soon the whale was wet

all over.

Slowly the sea came closer and closer. At last it covered the huge tail.

The village people ran back and forth carrying water, shouting to each

other. Yukio knew the whale would be saved.

Yukio’s father came and stood by him. “Thank you, Father,” Yukio said,

“for bringing the village people to help.”

“You are strong and good,” his father said, “But to save a whale many

hands must carry the water.”

Now the whale was moving with each new wave. Suddenly a great one lifted

him free of the rocks. He was still for a moment, then, with a flip of

his tail, swam out to sea.

The villagers watched silently, as the whale swam farther and farther

from their shore. Then they turned and walked toward the village.

Except for Yukio, who was asleep in the arms of his father.

He had carried a thousand pails of water, and he was tired.

You will find many other stories about life in Japan in your school or

public library. Here are three that you should enjoy: Story of the

Grateful Crane retold by Jennifer Bartoli; Momotaro the Peach Boy

edited by Ruth Tabrah; and The One-legged Ghost by Betty Jean

Lifton.